Appointed as the governor and Bosnian vizier Topal Sherif Osman Pasha (from 1861 to 1869), the era of great upheavals in the lives of the people in Bosnia and Herzegovina began. By implementing the sultan’s reforms, he contributed significantly to the progress of Sarajevo as well as the entire Bosnia and Herzegovina. Evidence from historical documents confirms that he was a pioneer in the creation of modern Sarajevo urbanism. Through the construction of important buildings in the city requiring larger amounts of wooden materials, he built the first sawmills (initially water-powered, later steam-powered), bringing engineers from Vienna. These same engineers taught the local community how and what to cut, how to thin forests essentially for the preservation for future generations. During the period of organizing and implementing reforms, efforts were made to establish the first forestry inspectorates. Austrian forestry experts at that time generally assessed that there were compact and untouched forest areas with significant timber resources across Bosnia and Herzegovina.

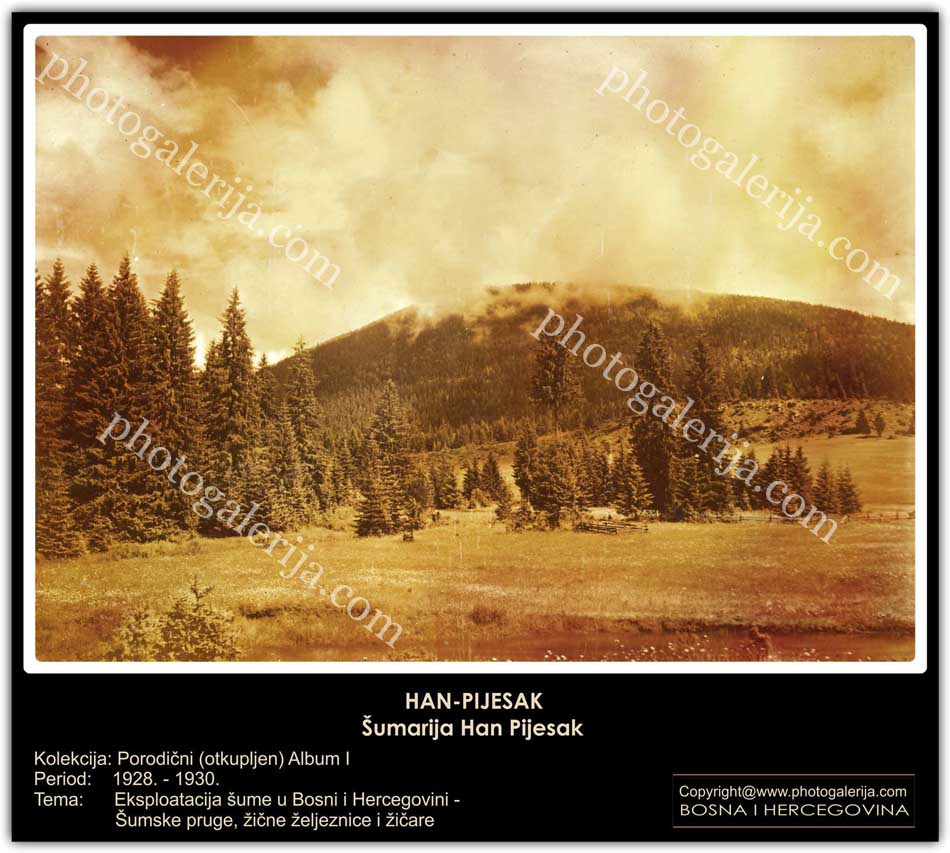

After the occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary acquired possession of vast natural resources, including forests. The new organization of forestry and the forestry service subordinated them to the main goal, which was the rapid and intensive exploitation of the Bosnian forests. Foreign capitalist enterprises at that time entered into long-term contracts with the Federal Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly based on free agreements. During this period, foreign construction companies expressed the need for supplying railway sleepers to commence the construction of railway lines: Dobrljin-Banja Luka (1872), Bosanski Brod – Sarajevo (1879/82), Sarajevo – Metković (1885/91), Lašva – Travnik – Bugojno – Donji Vakuf (1893/95), Zavidovići – Olovo – Han Pijesak – Kusaće (1901/02), Sarajevo – Uvac (1901/06), etc.

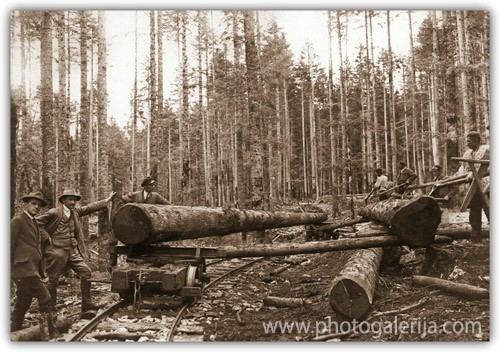

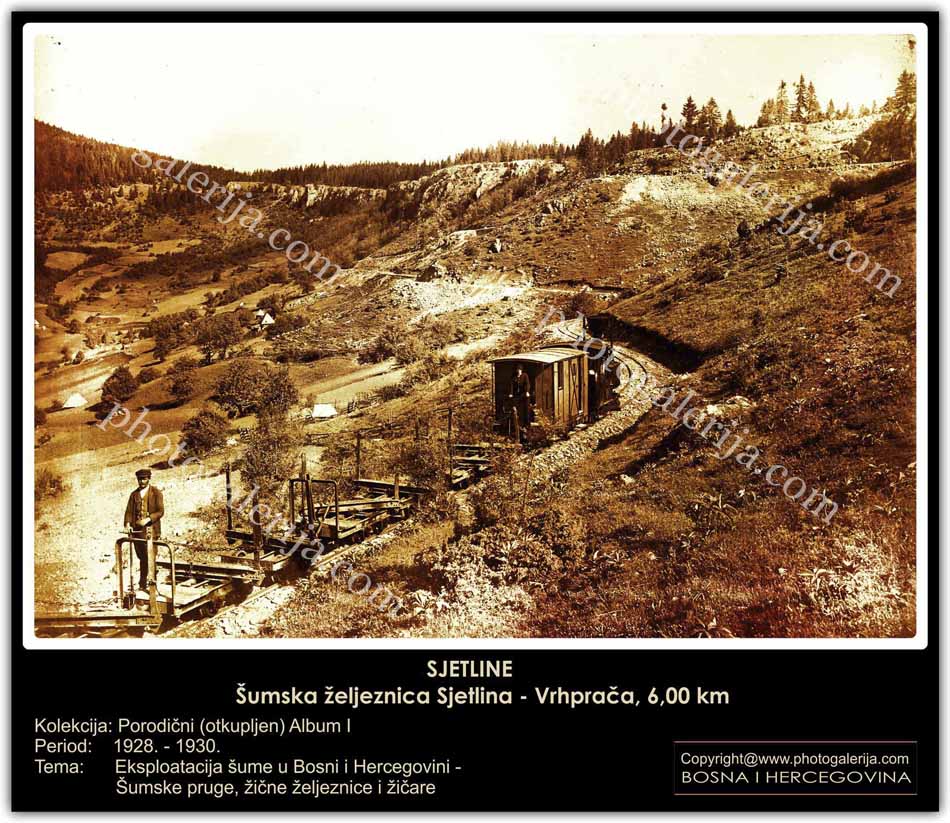

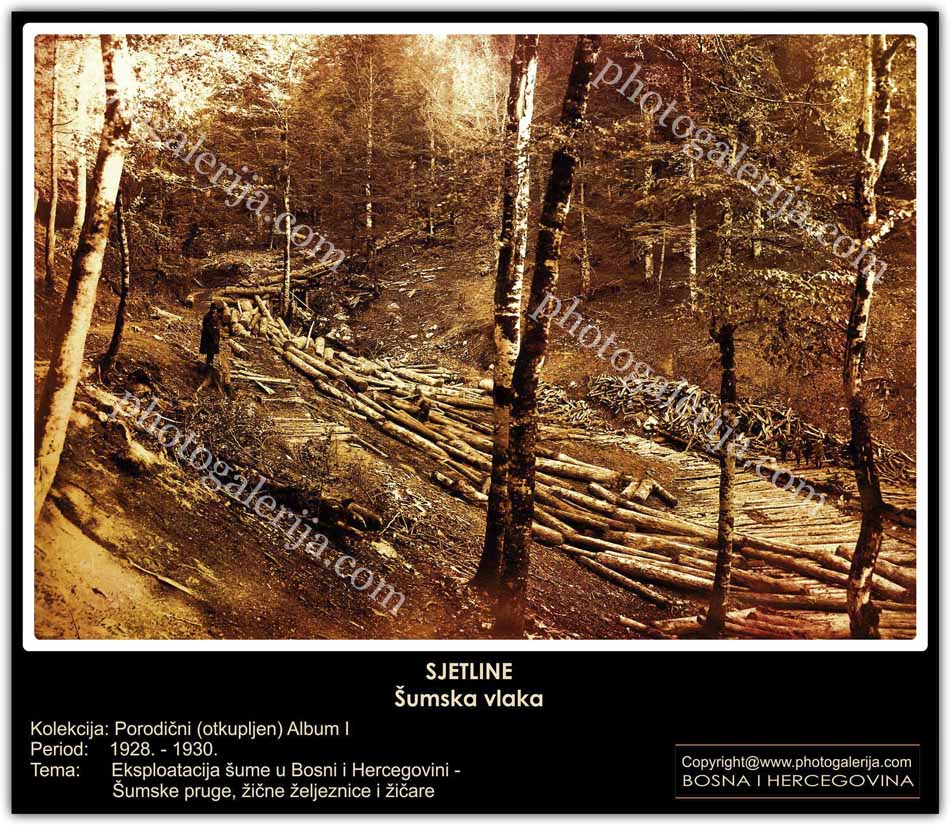

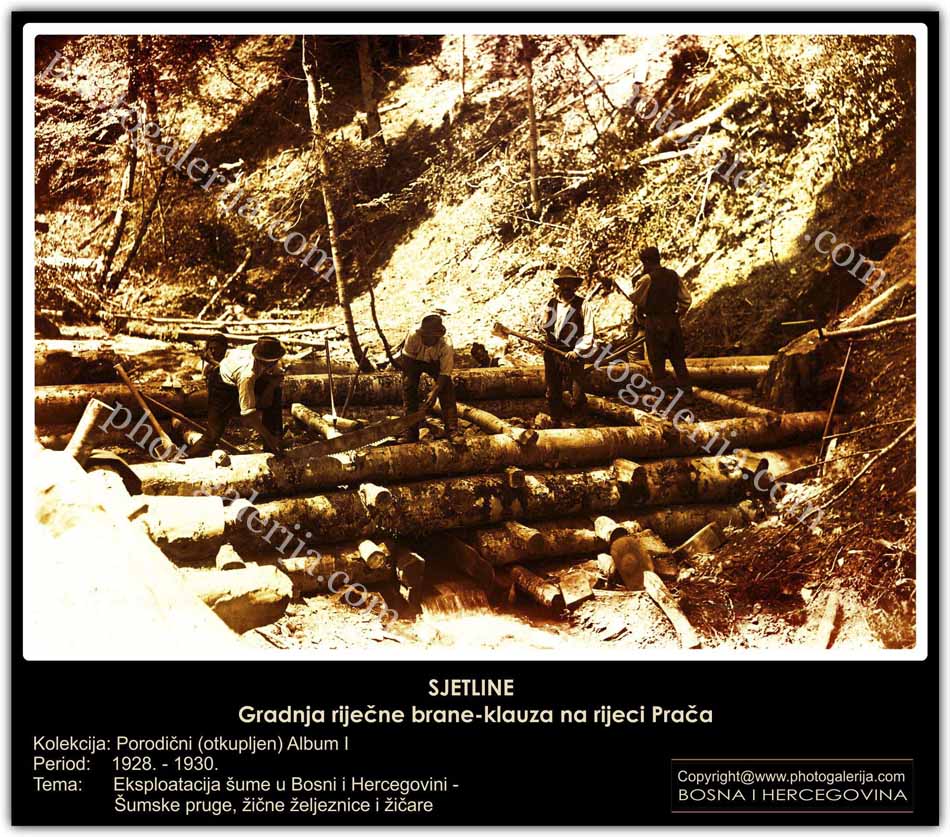

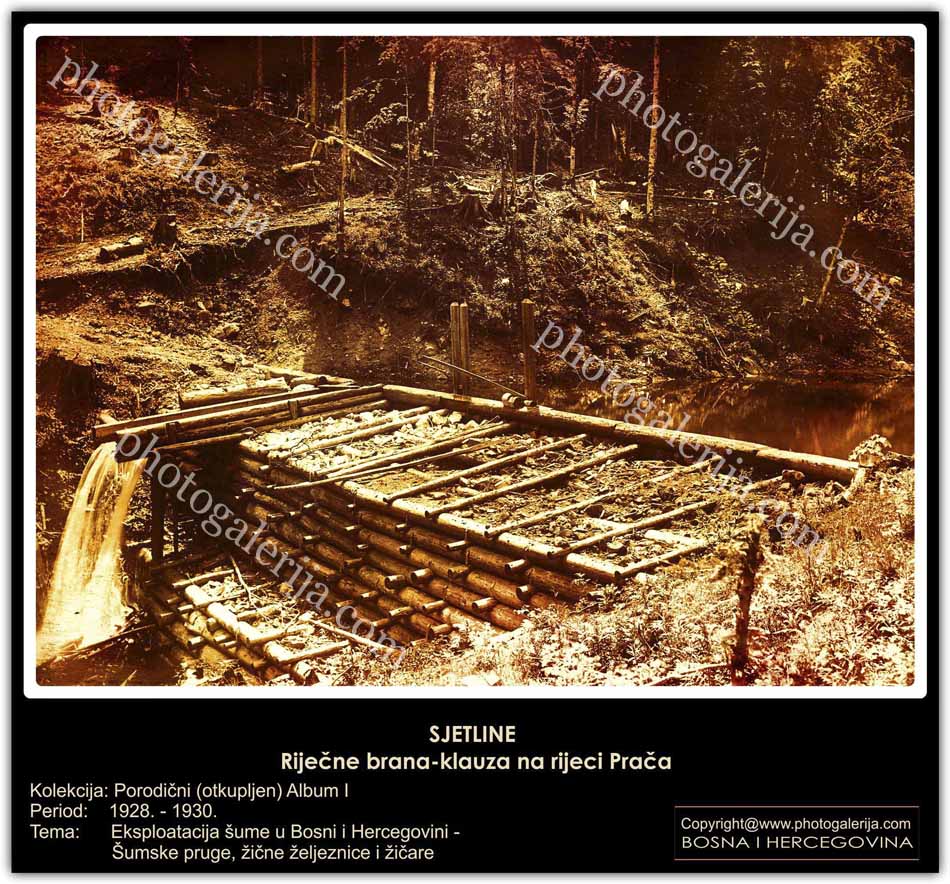

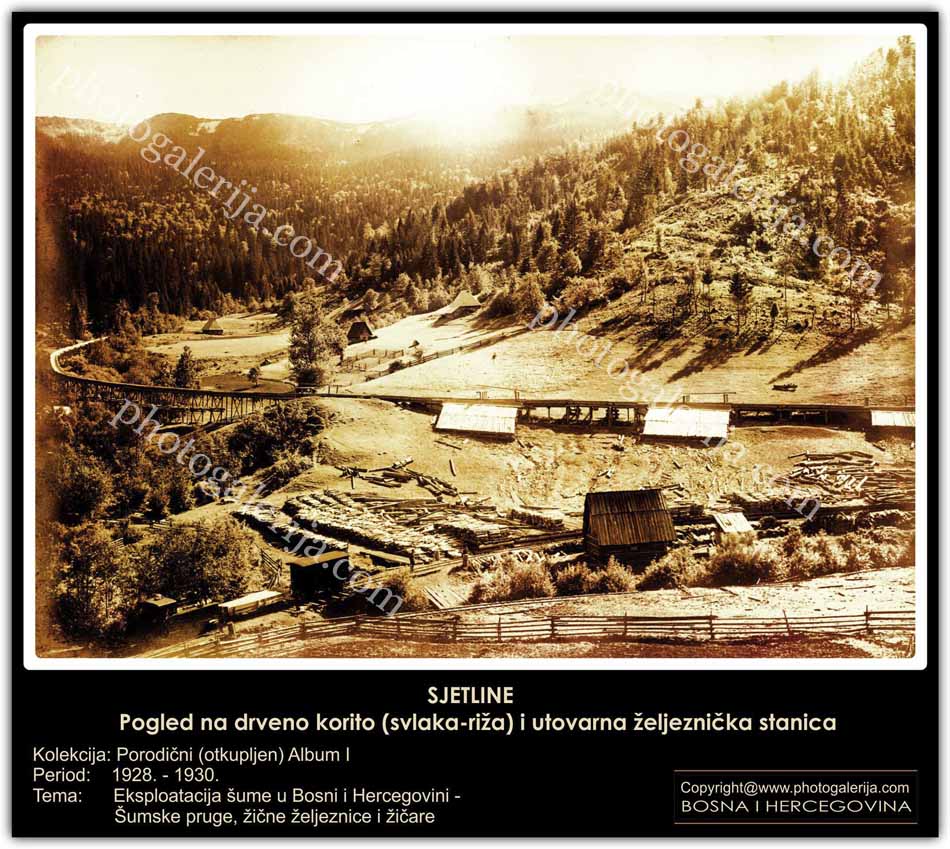

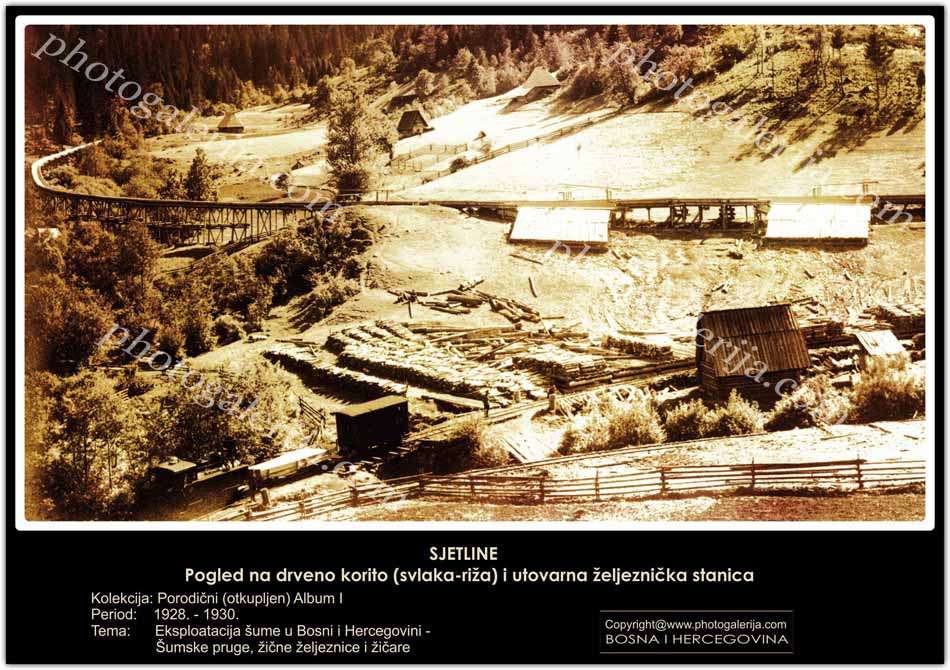

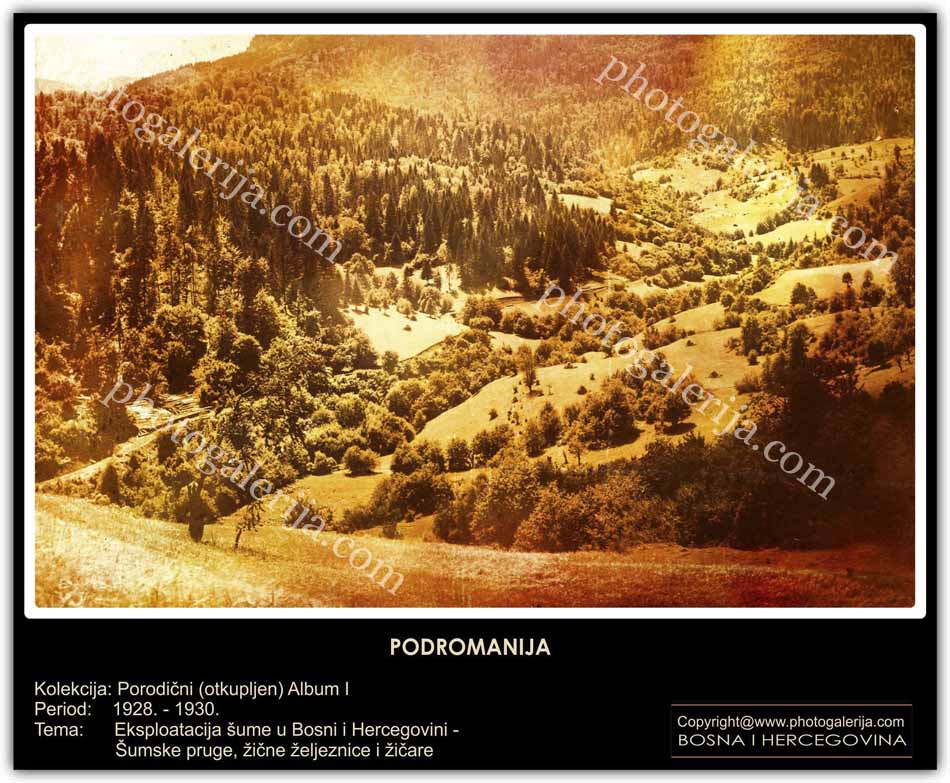

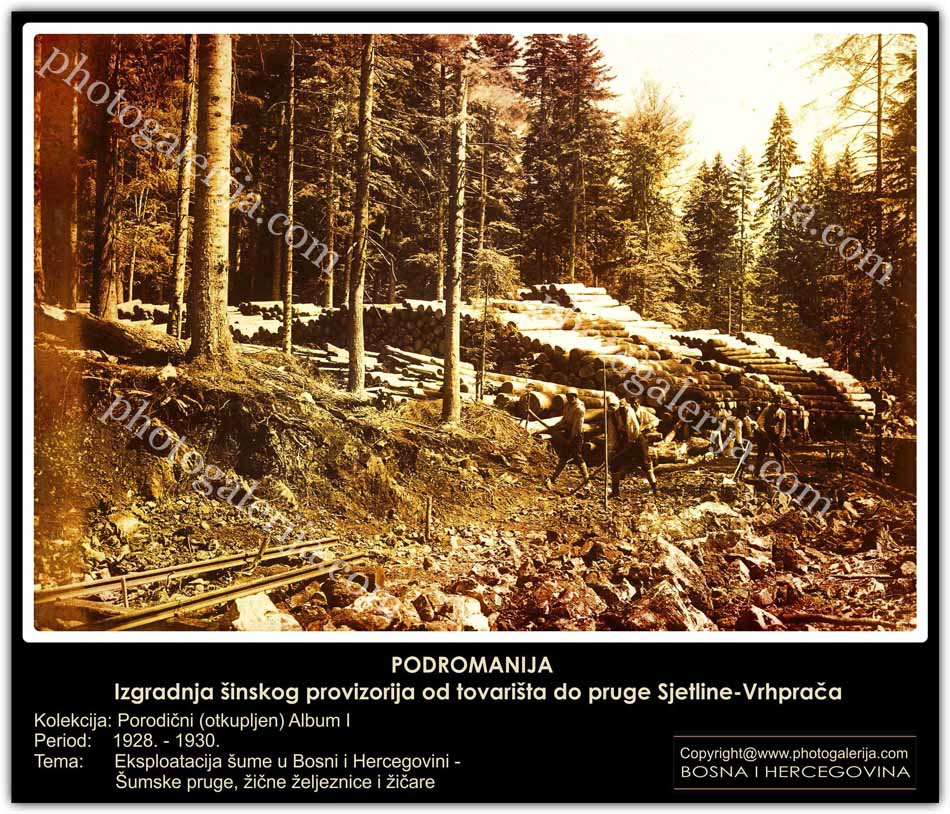

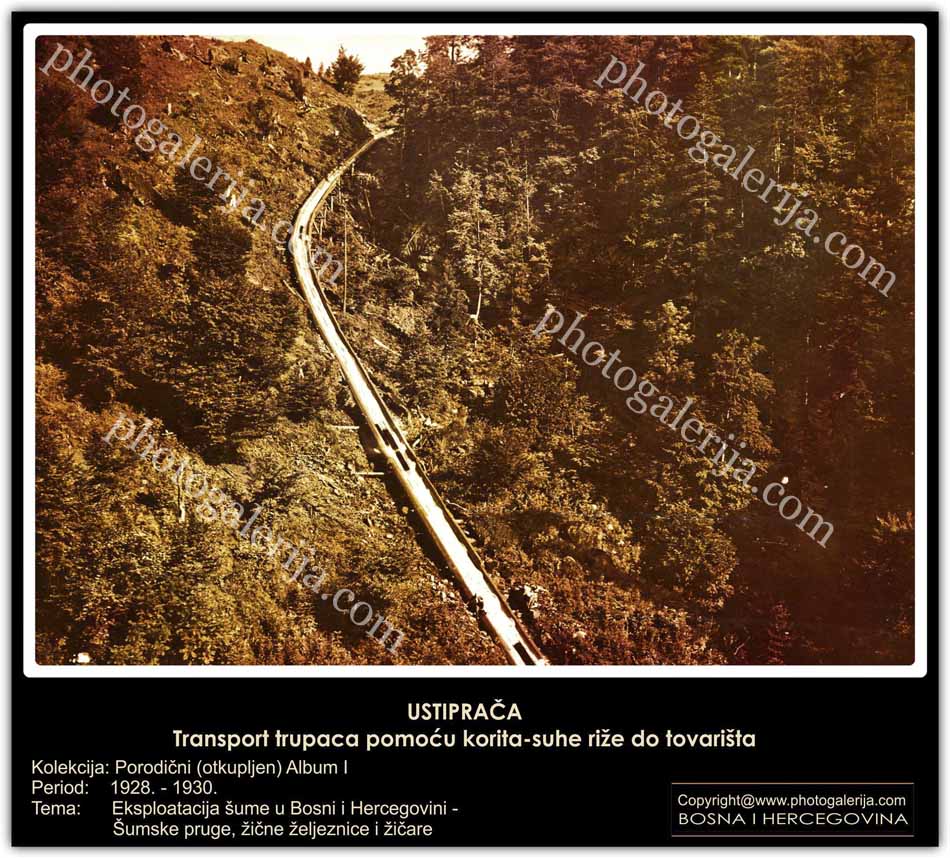

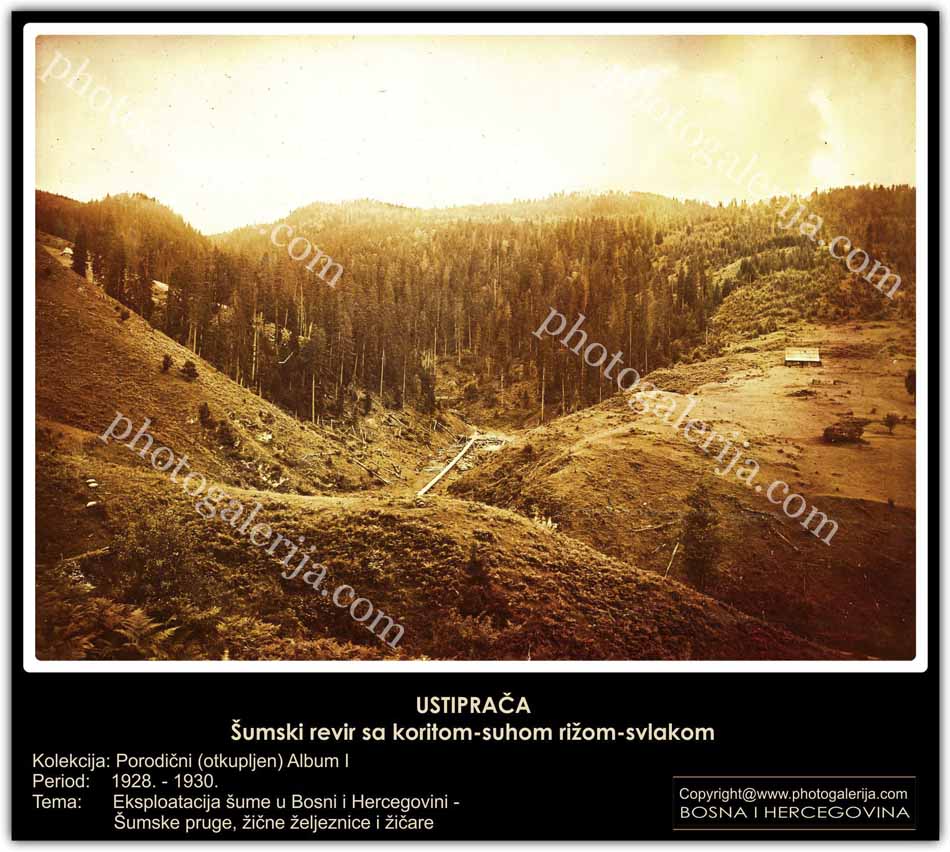

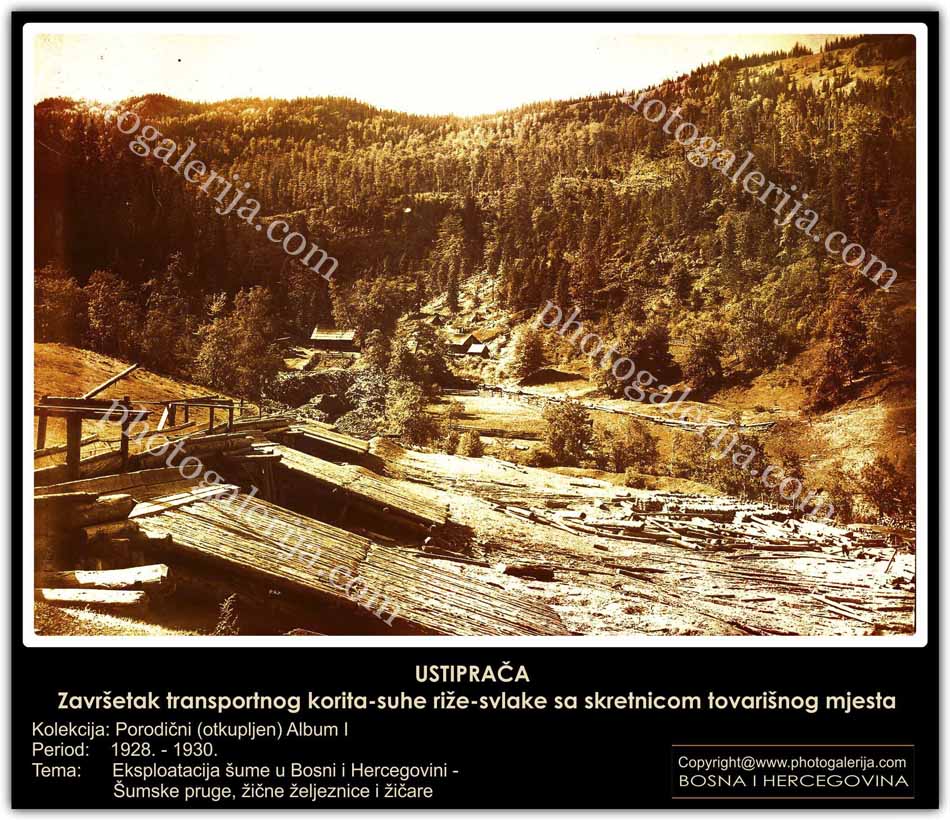

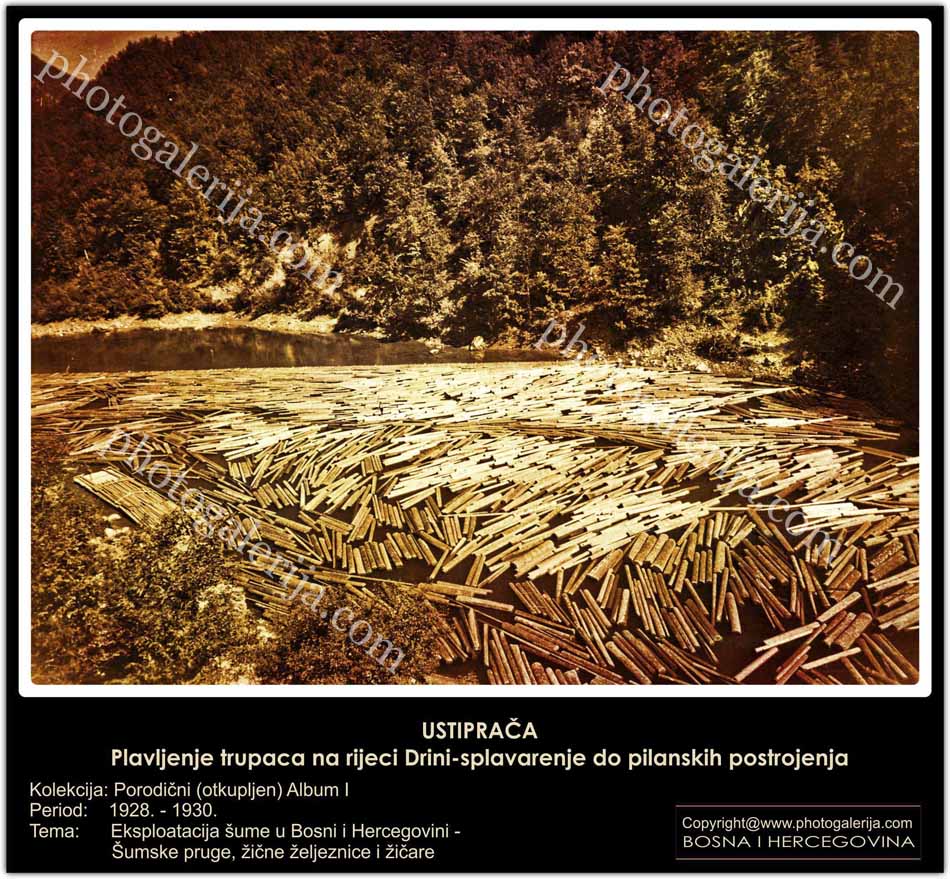

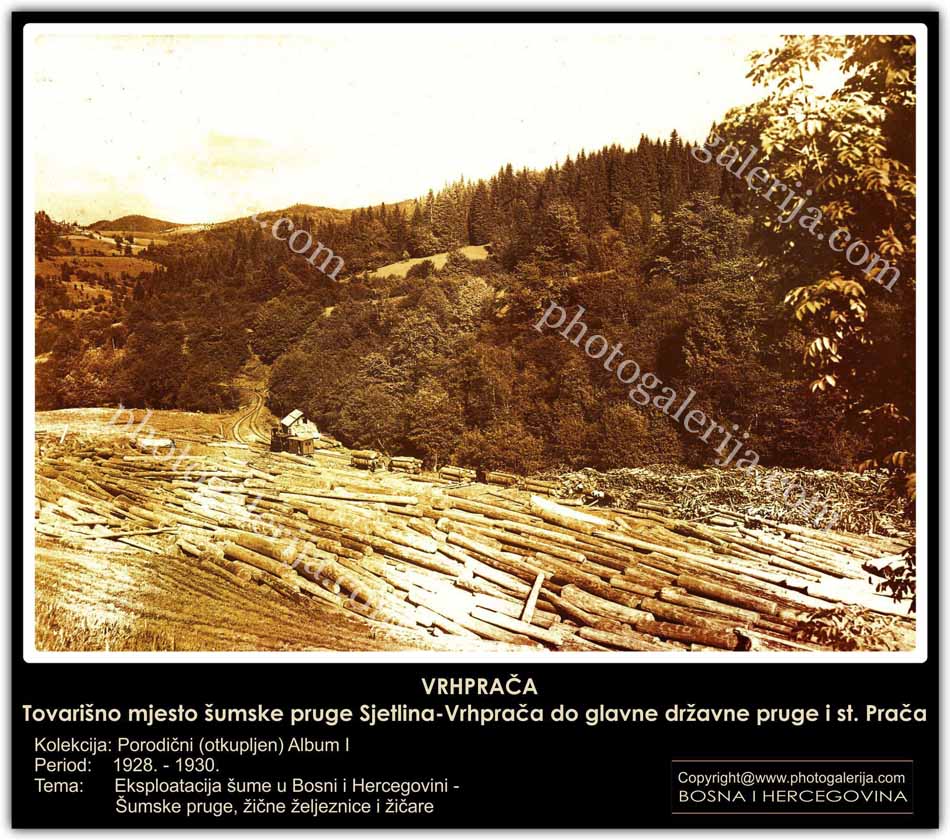

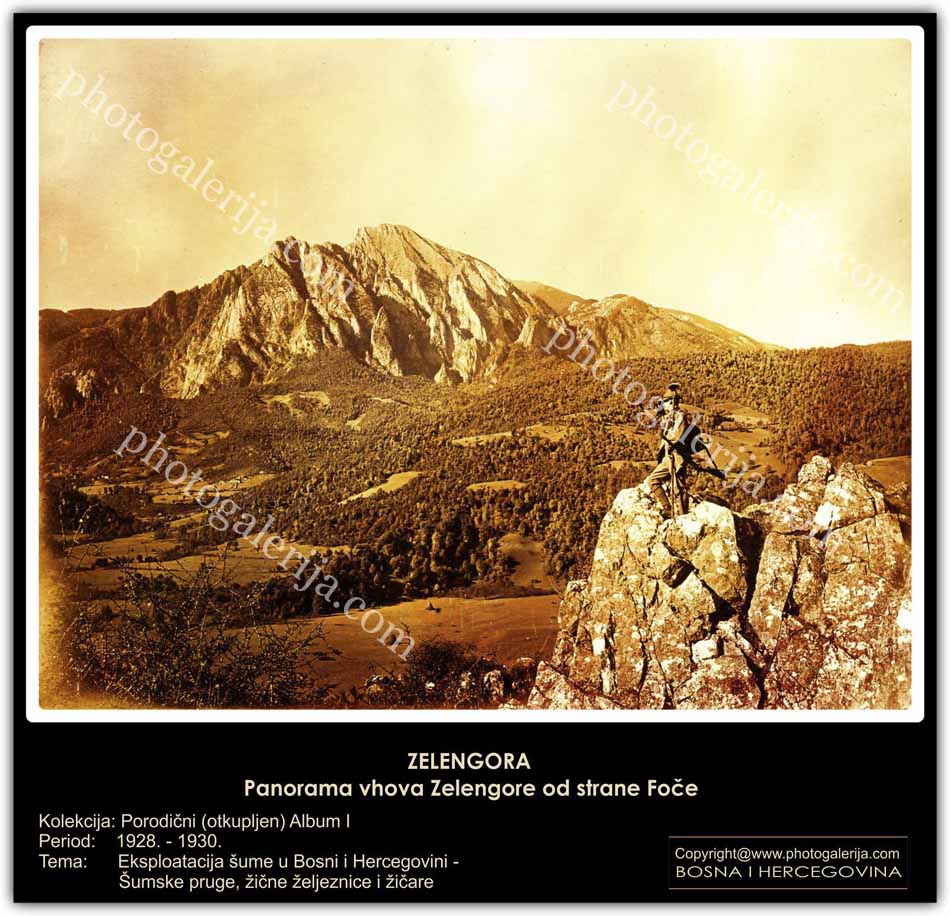

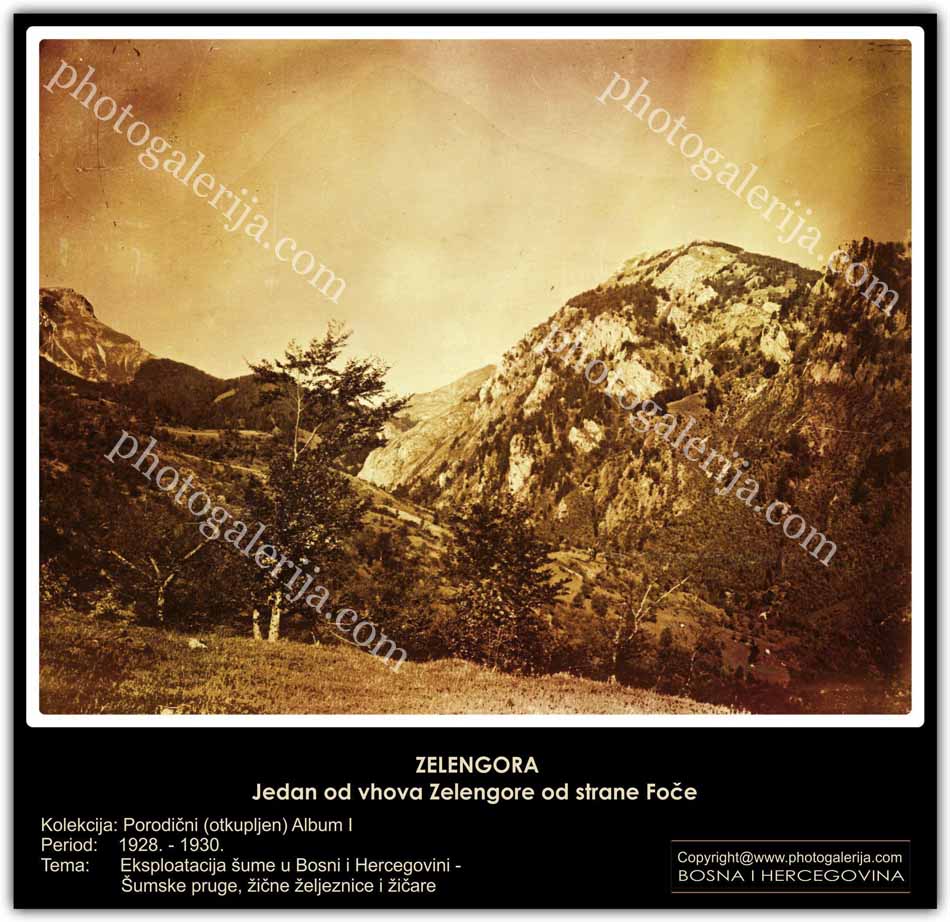

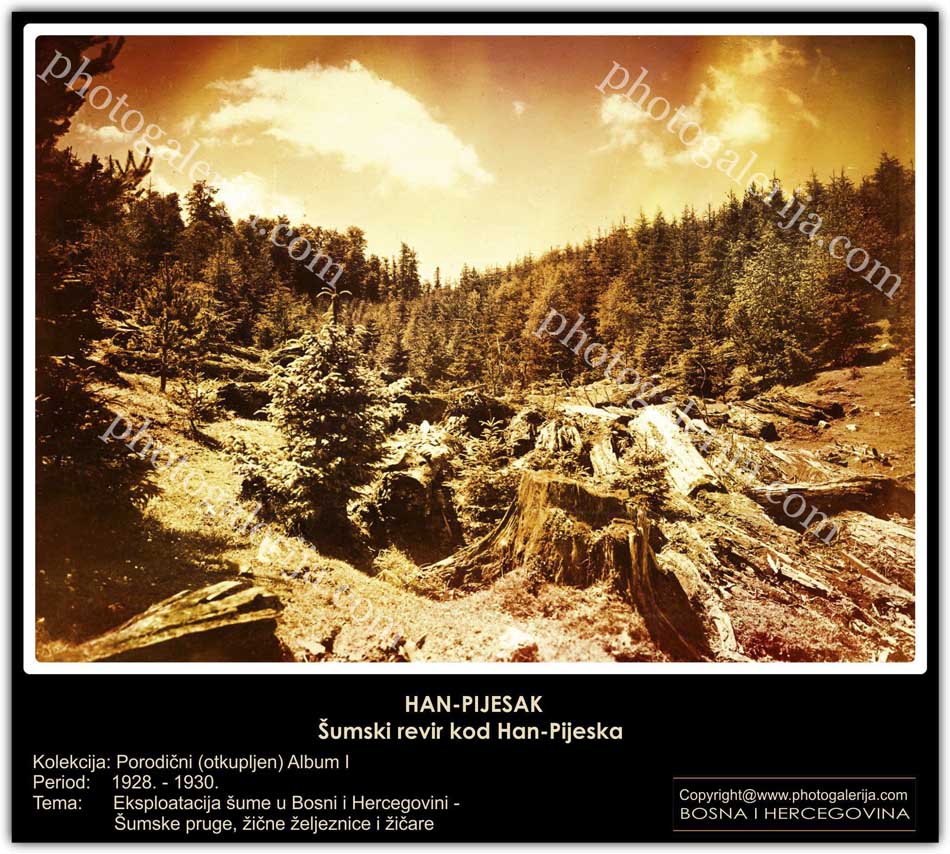

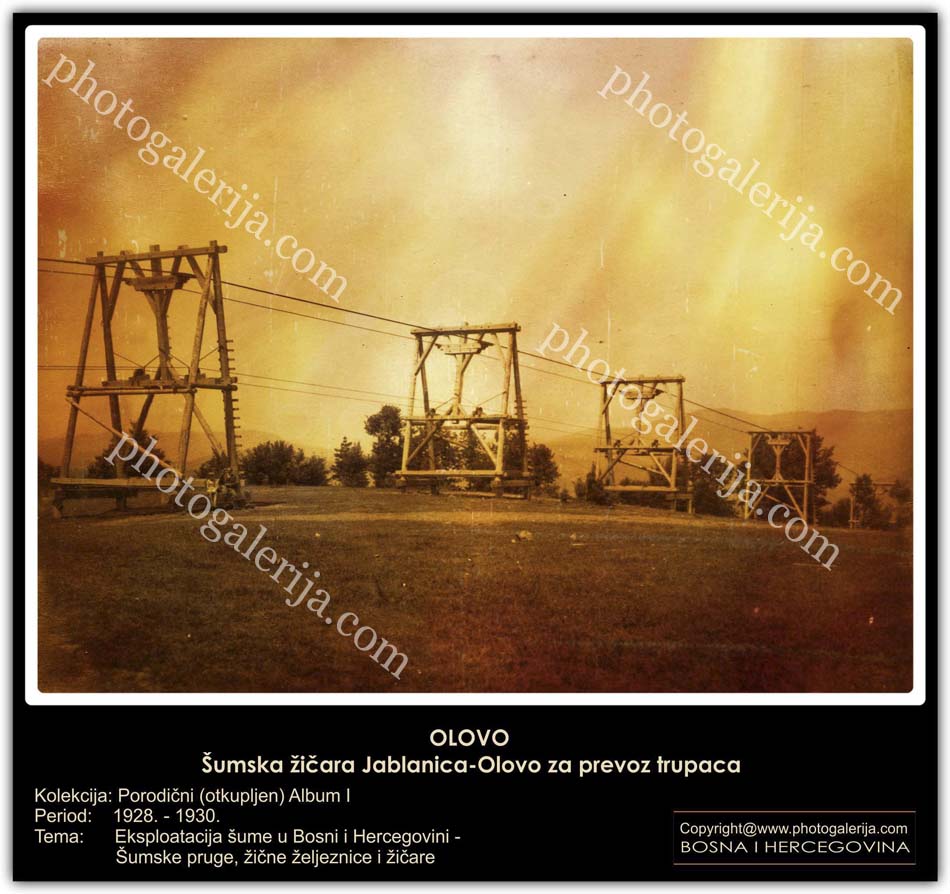

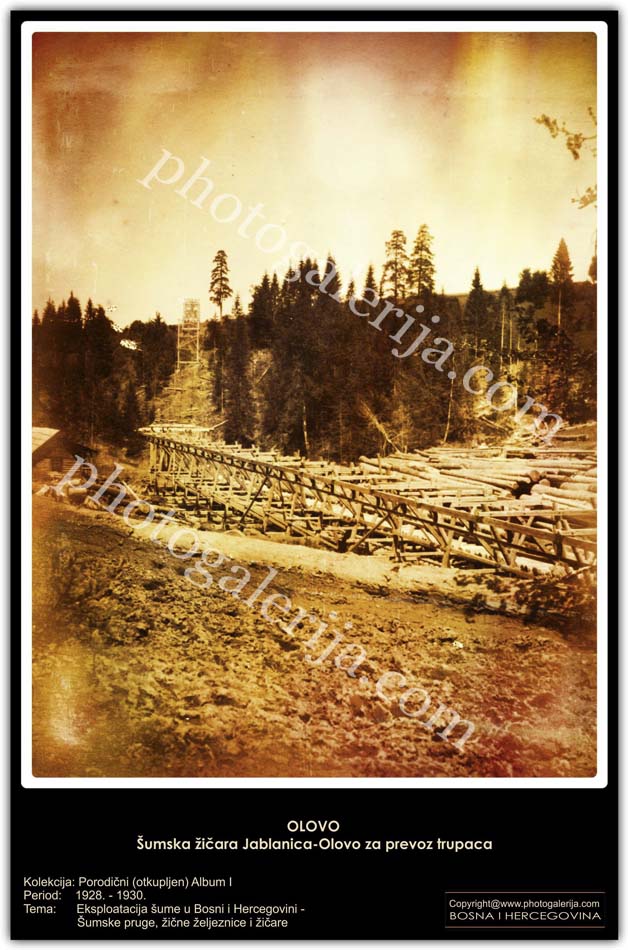

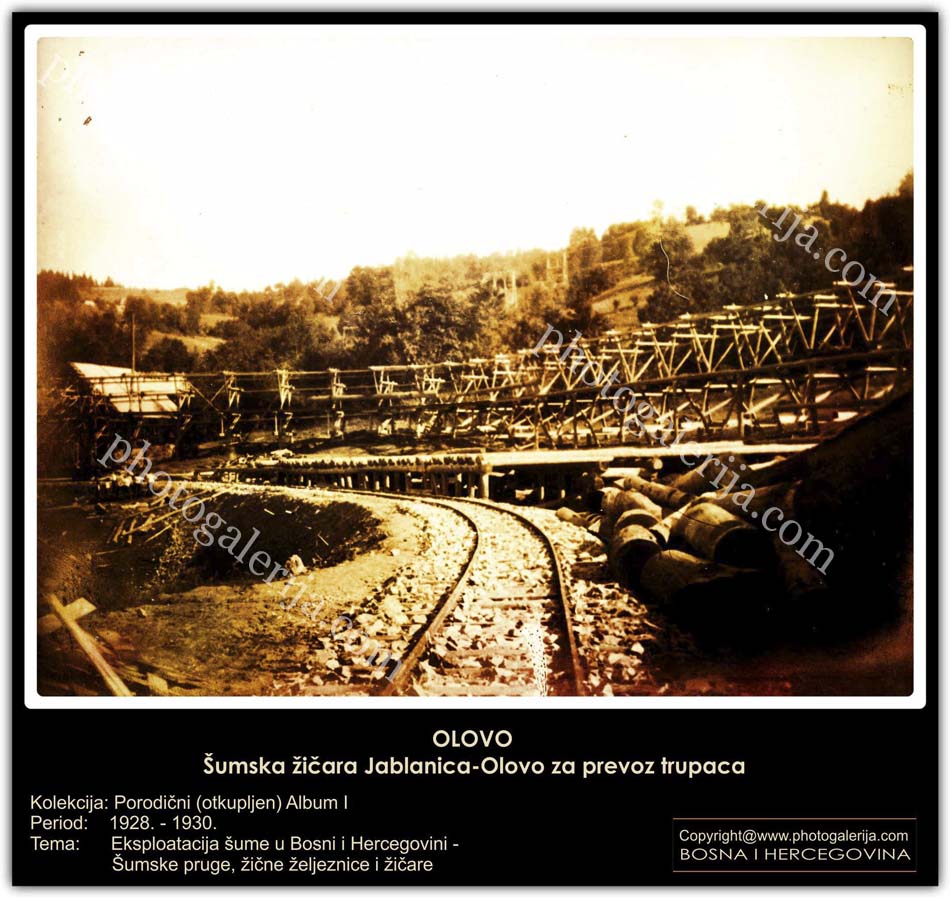

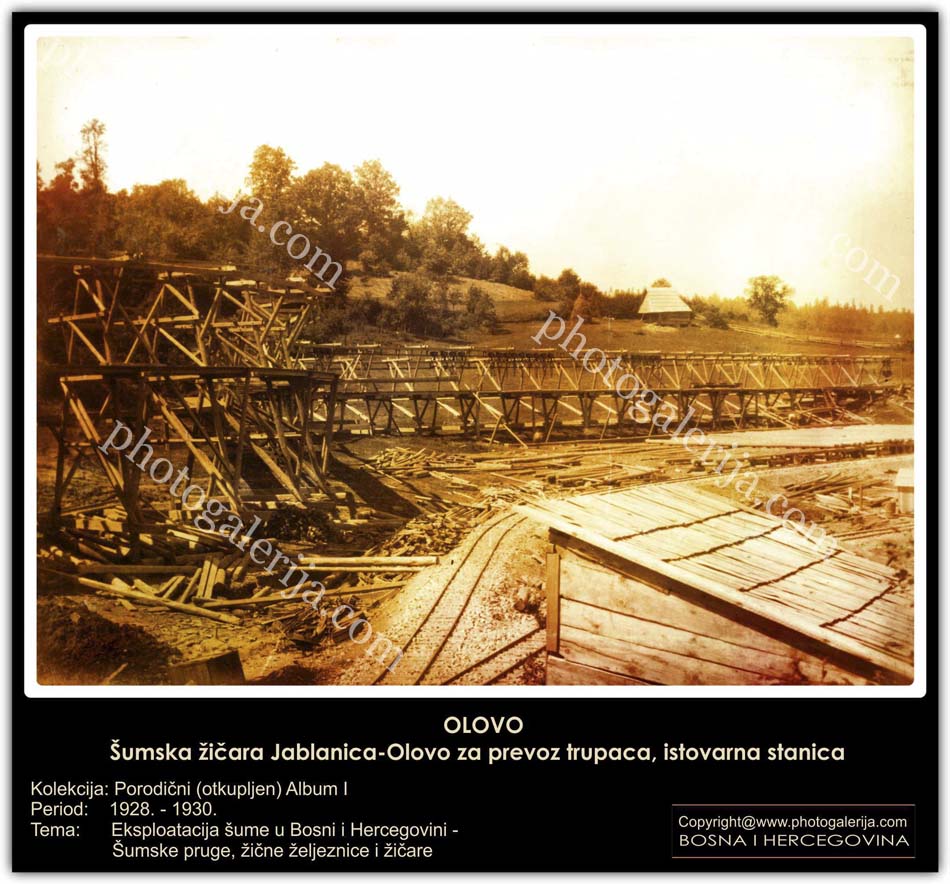

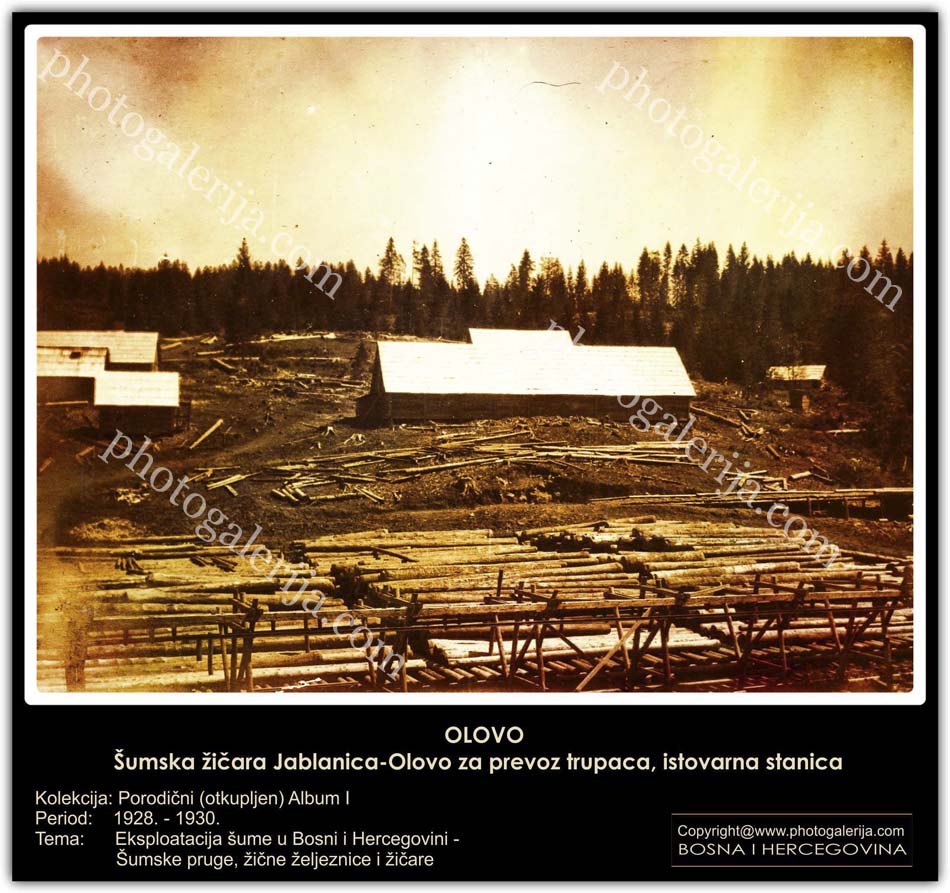

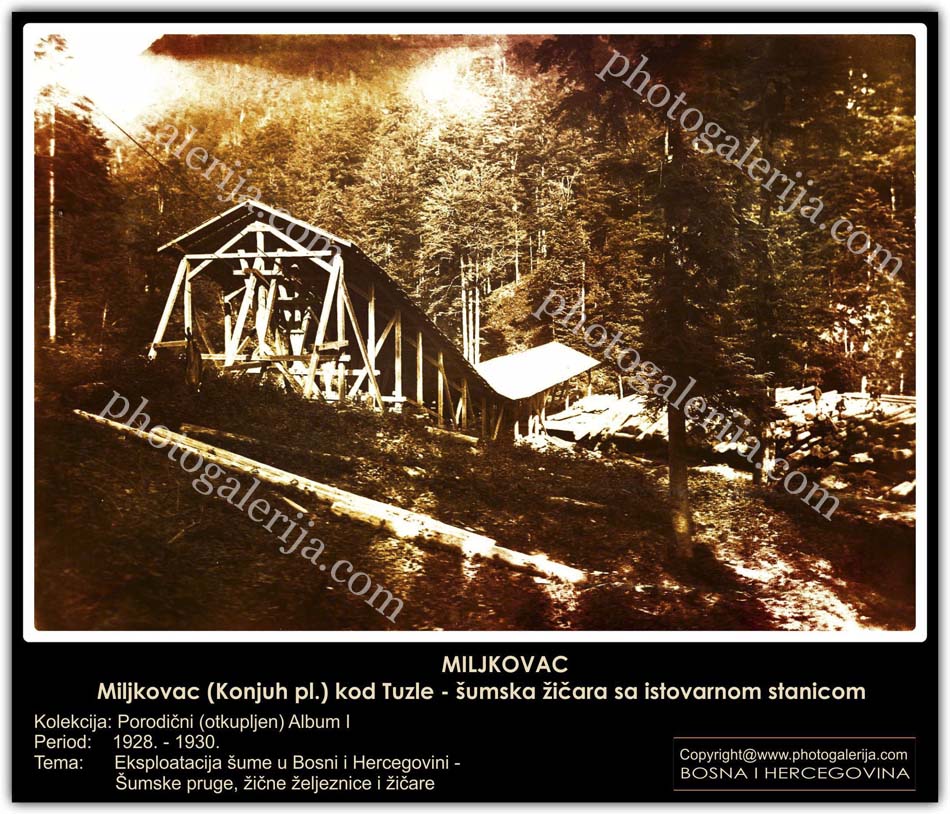

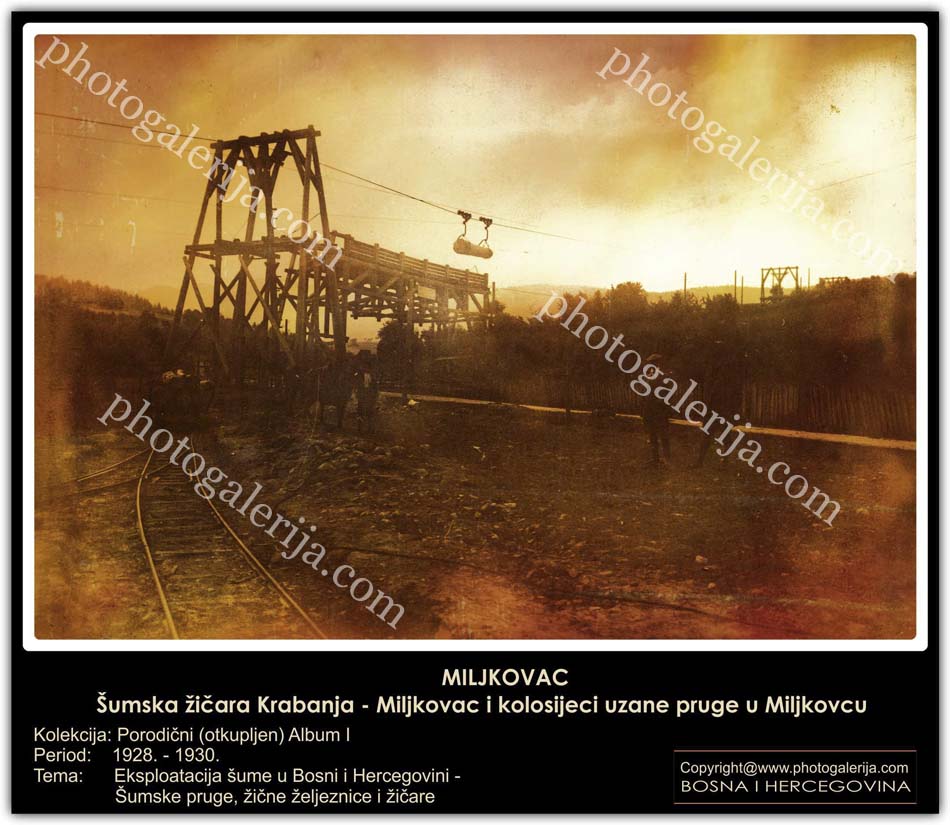

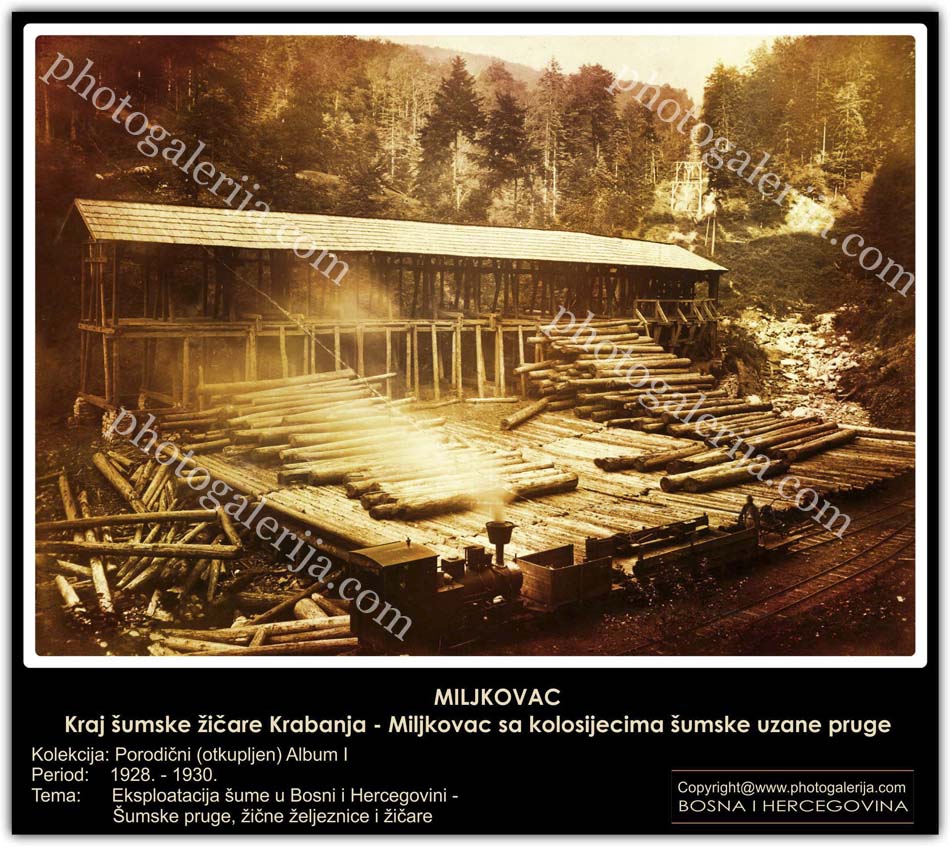

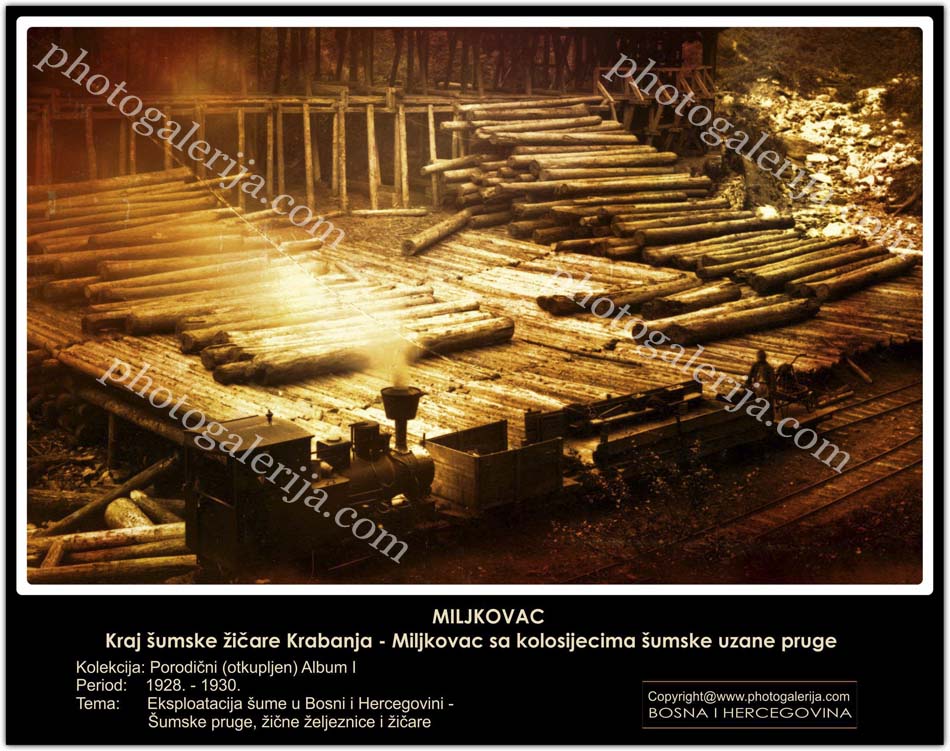

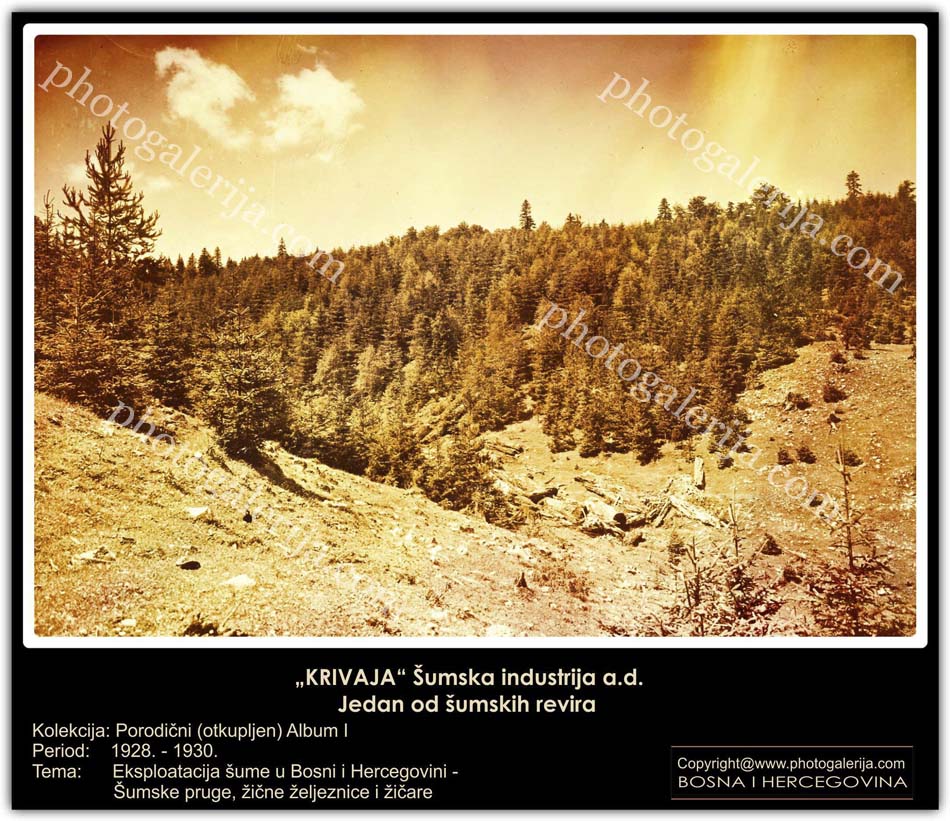

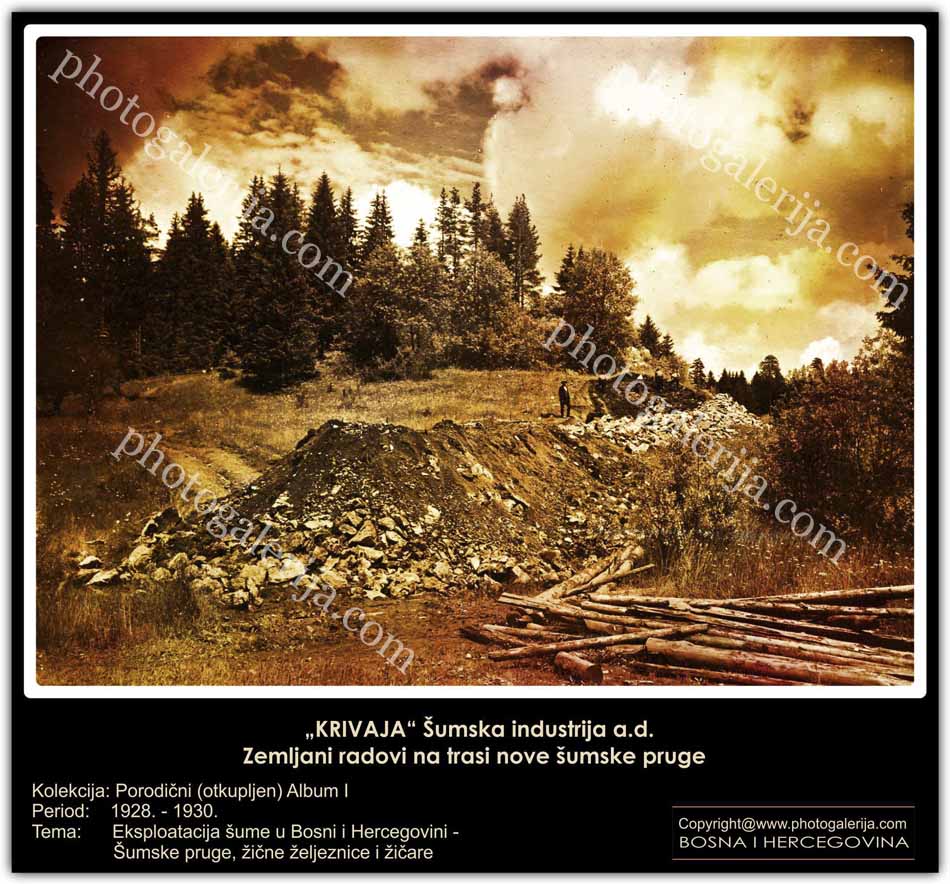

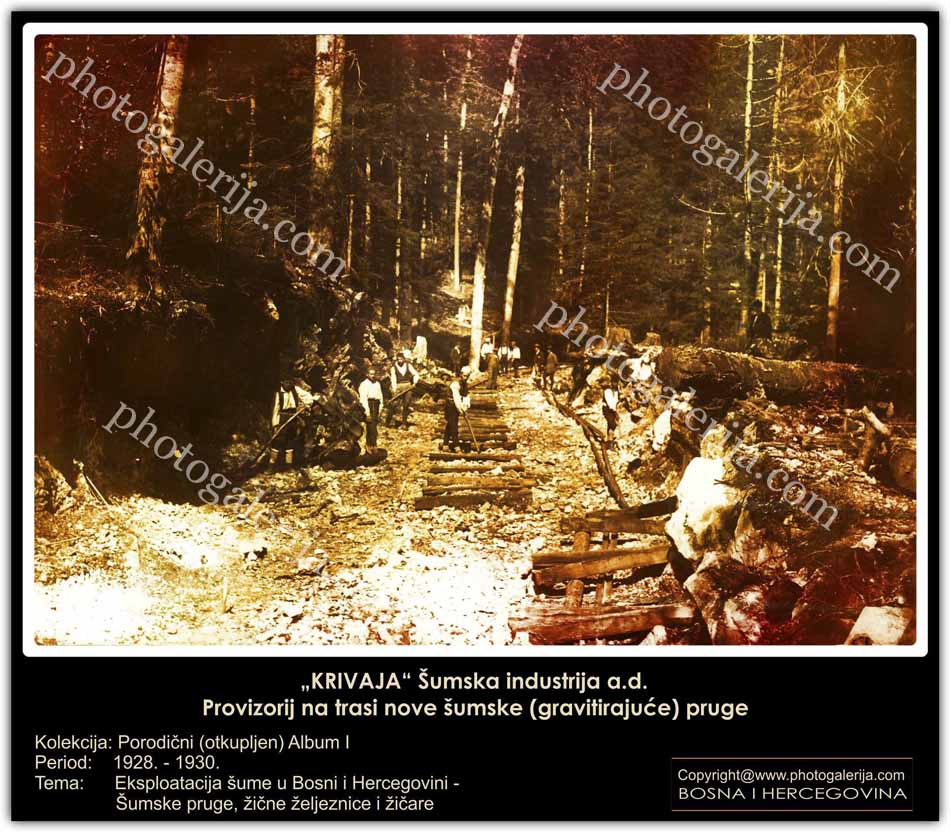

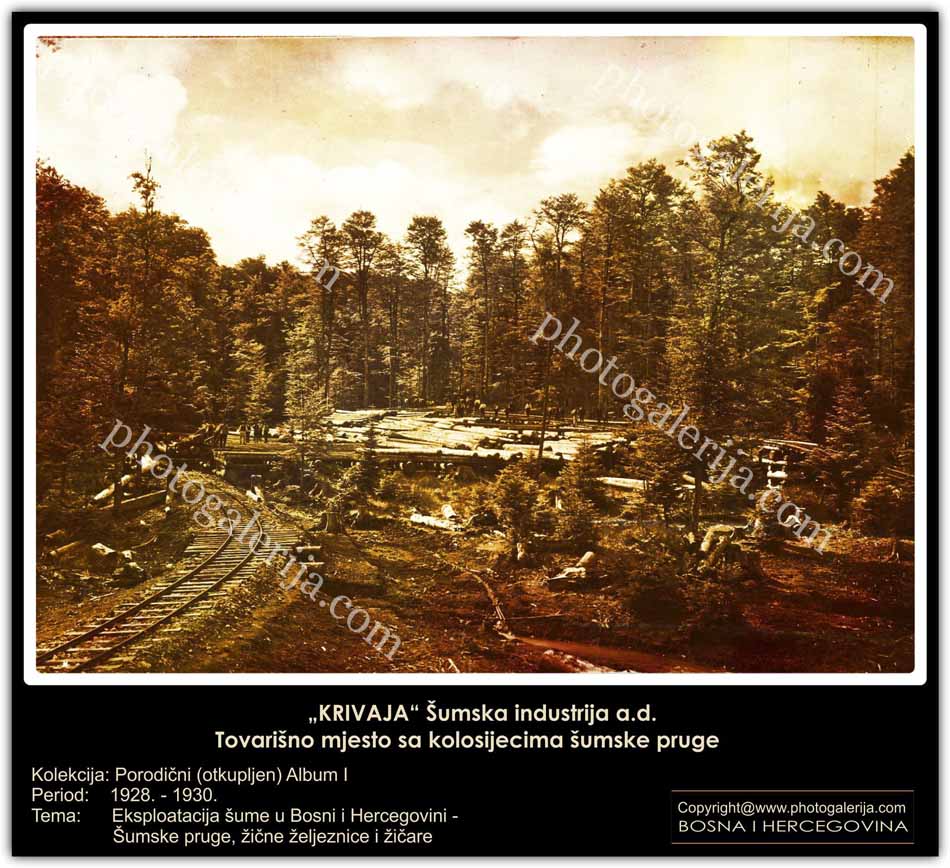

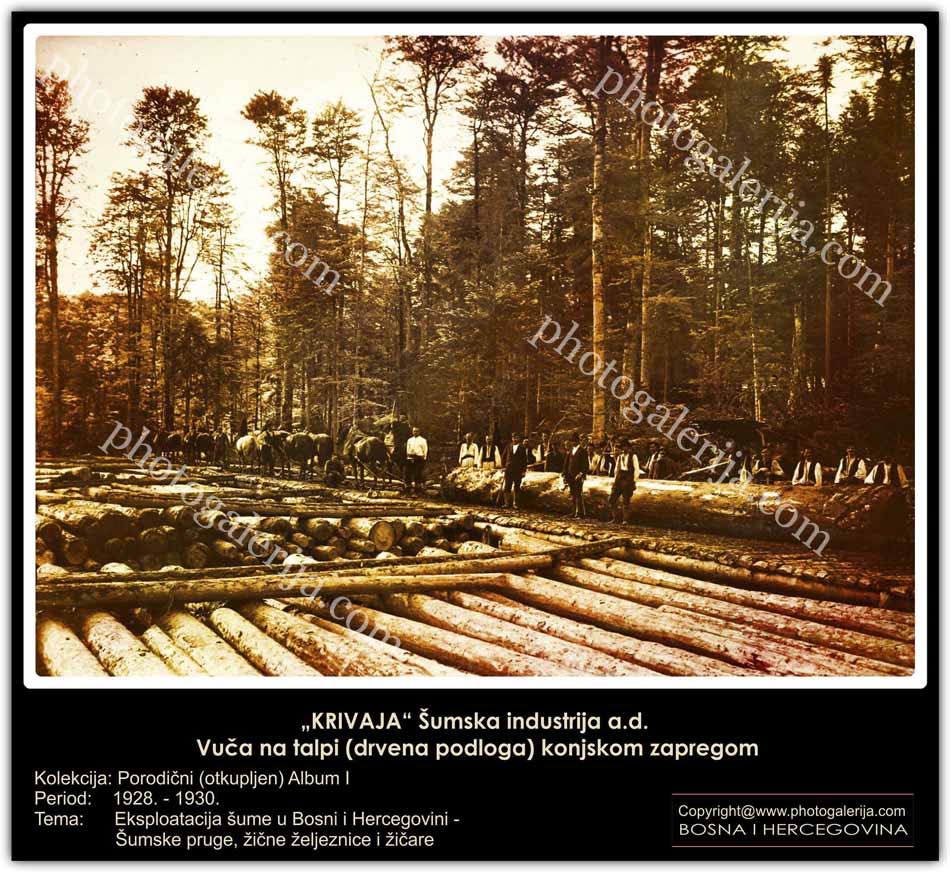

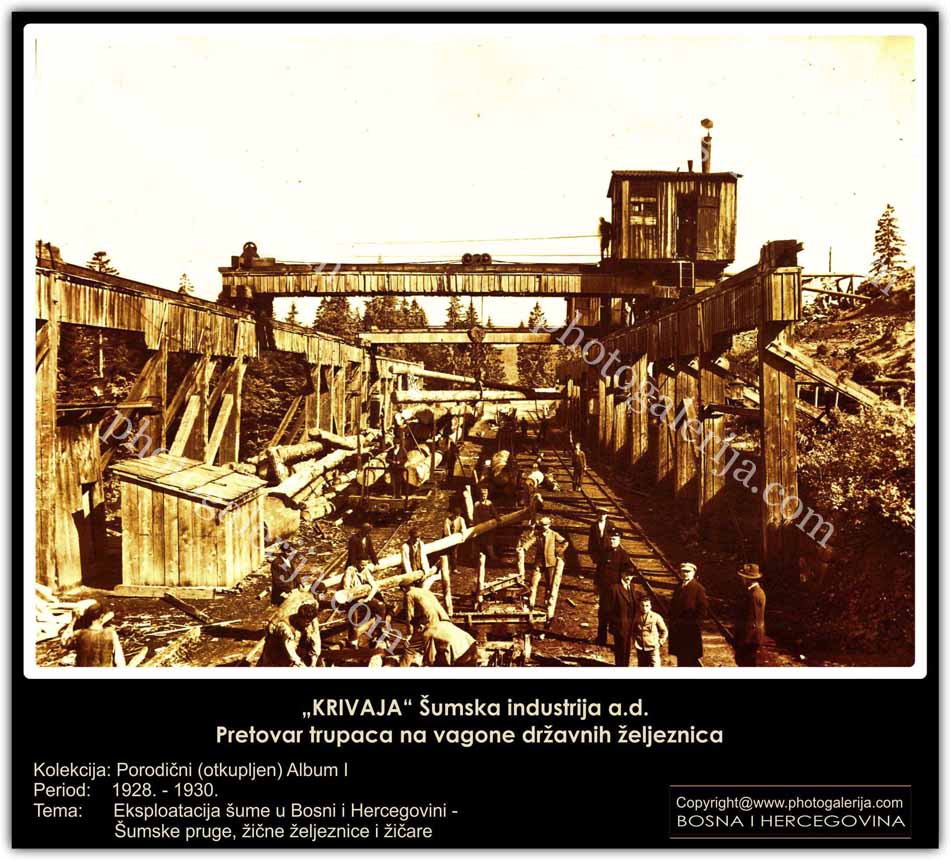

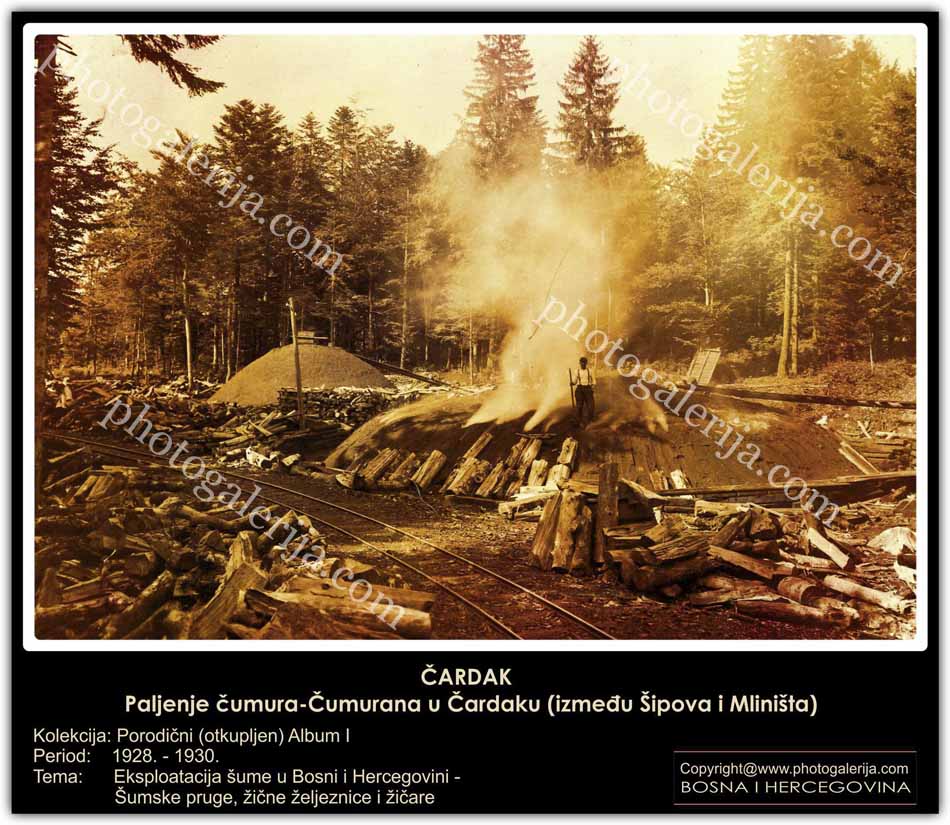

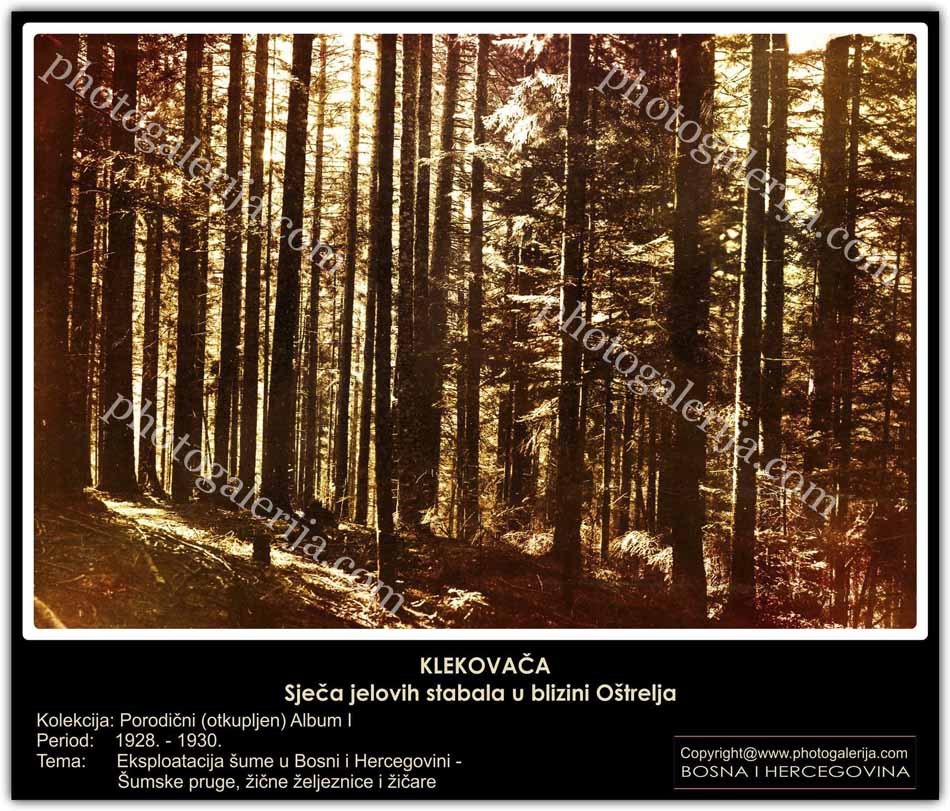

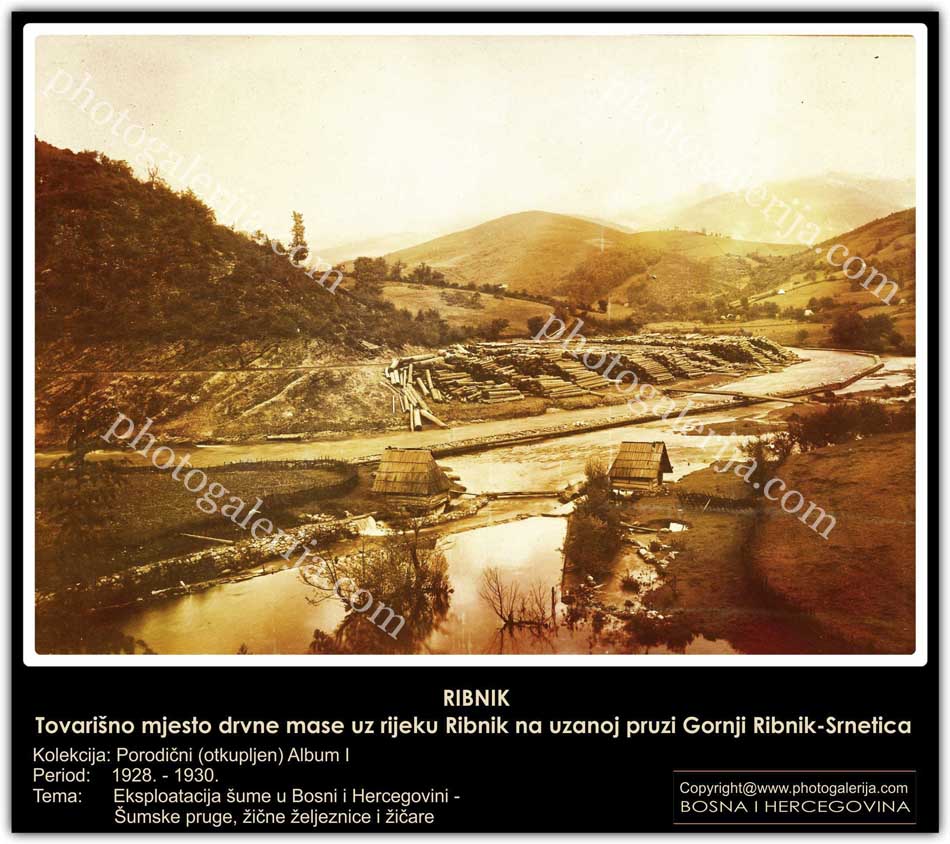

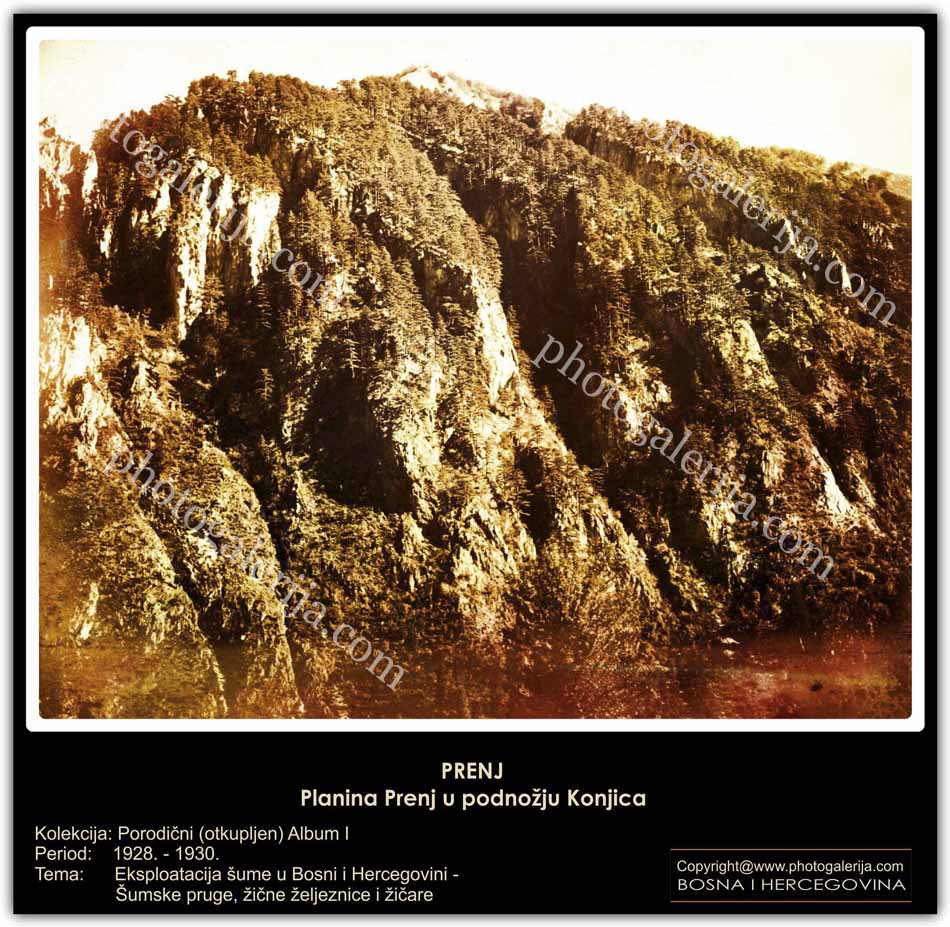

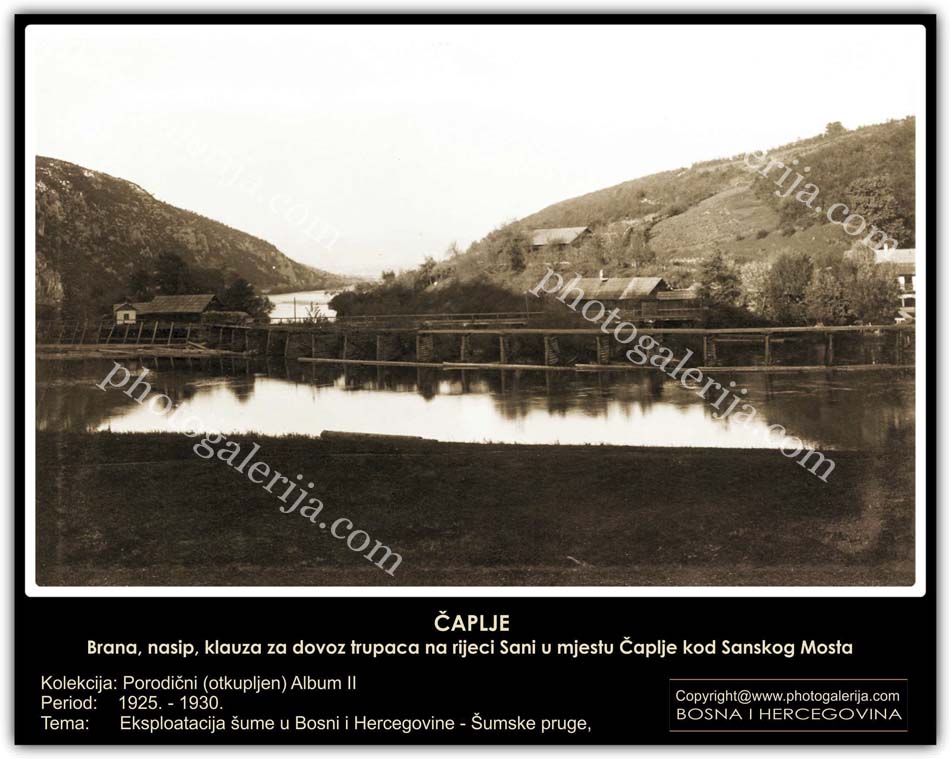

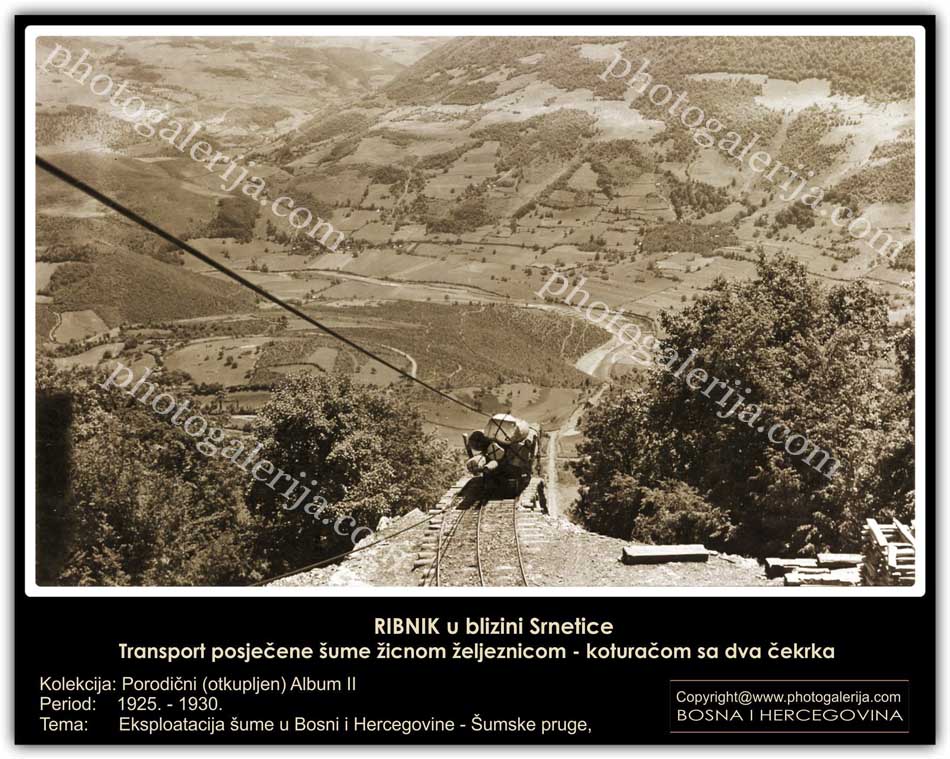

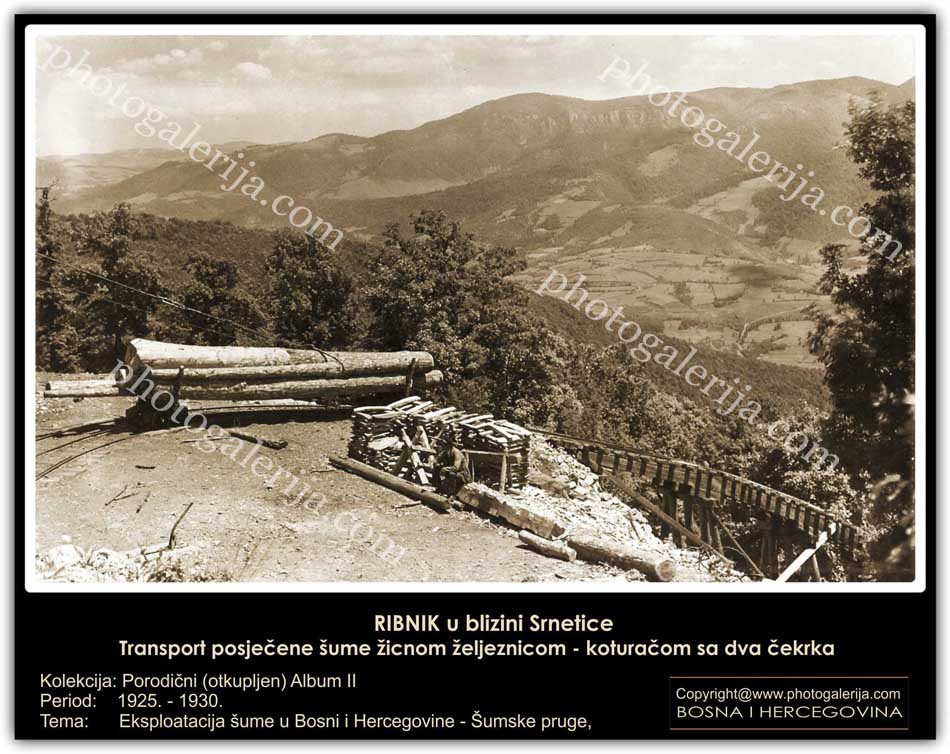

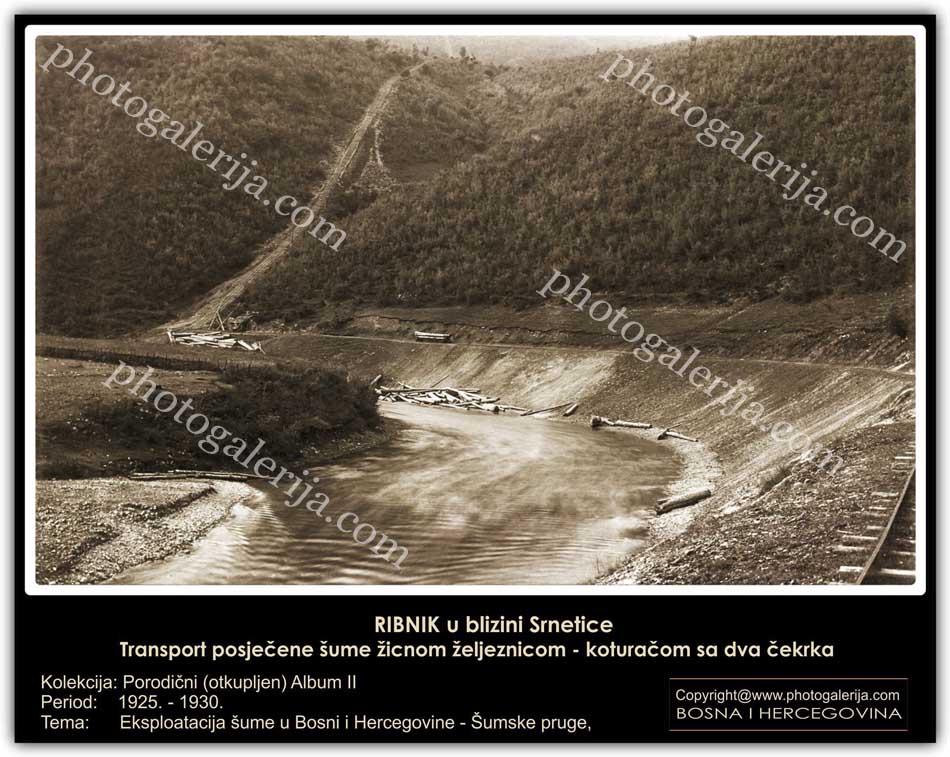

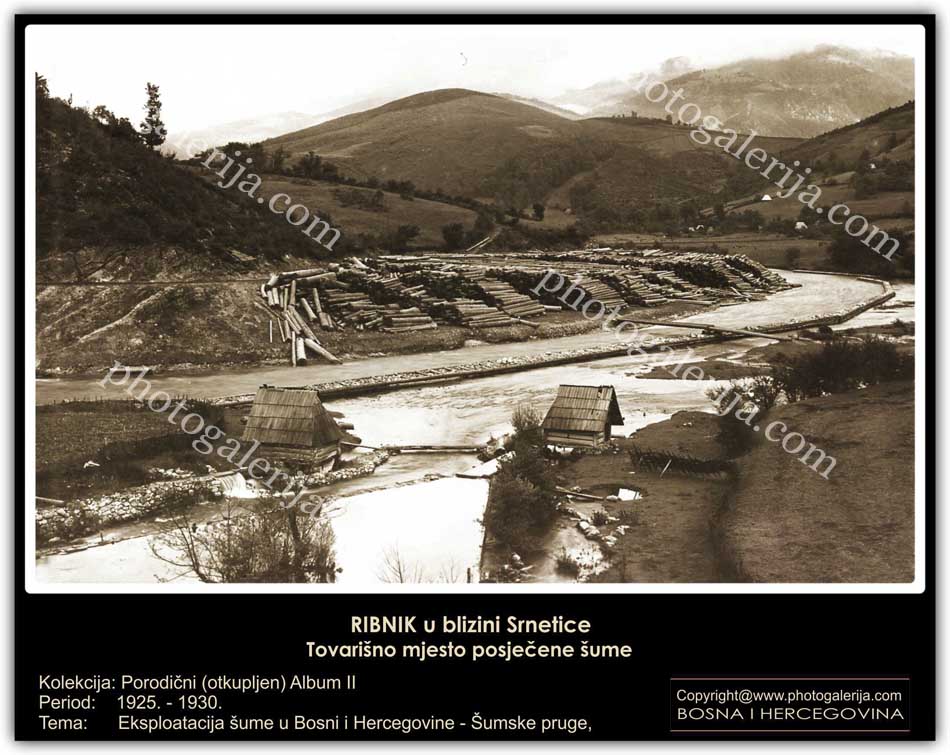

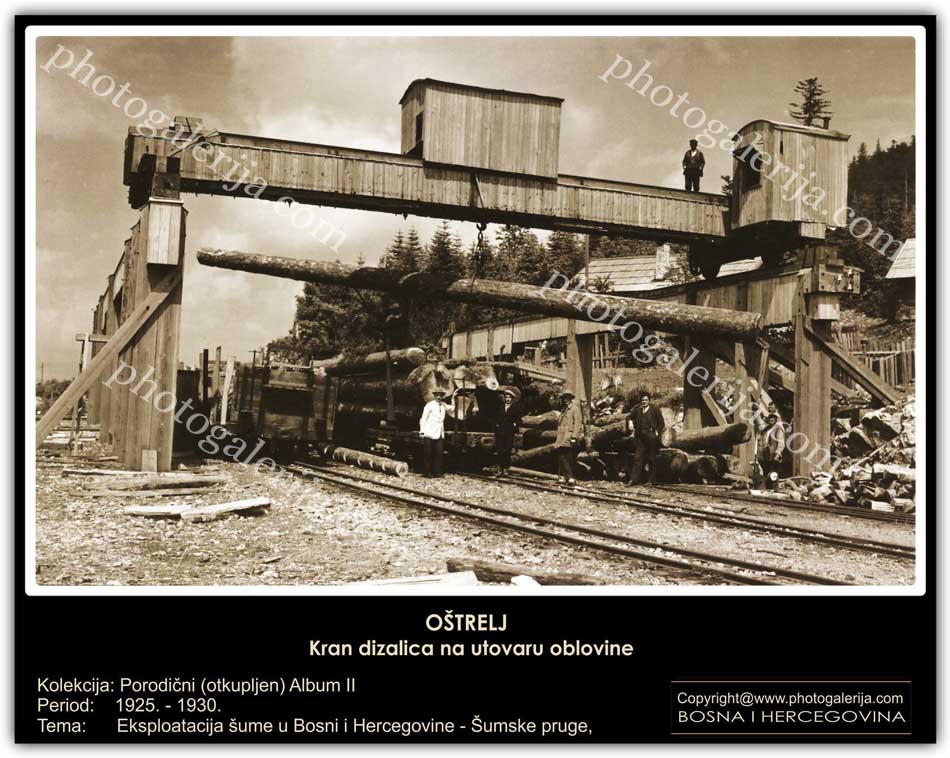

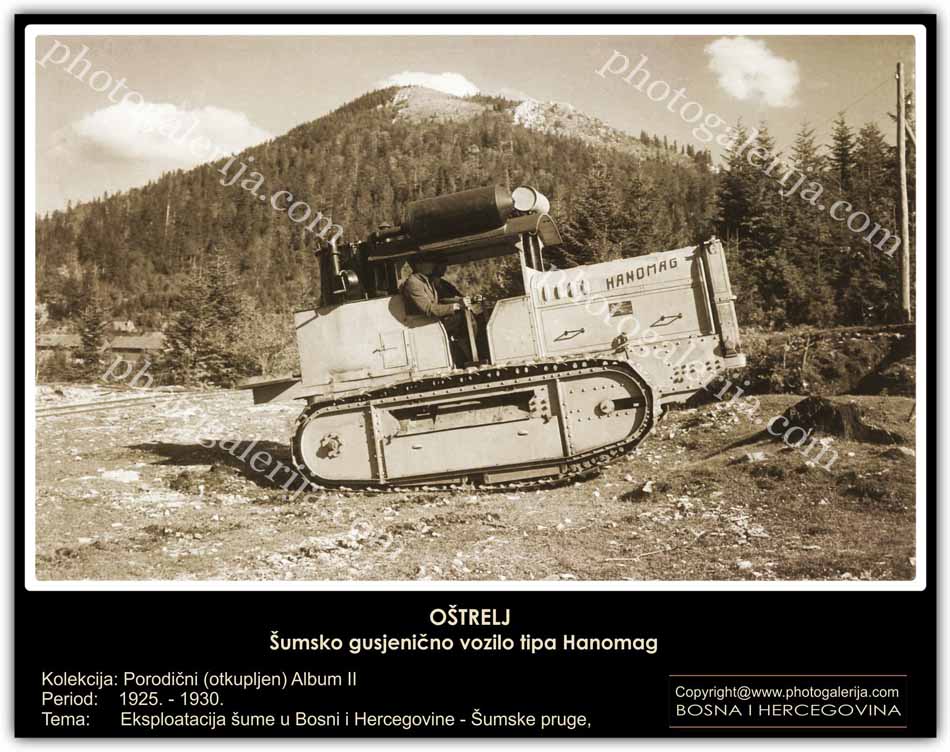

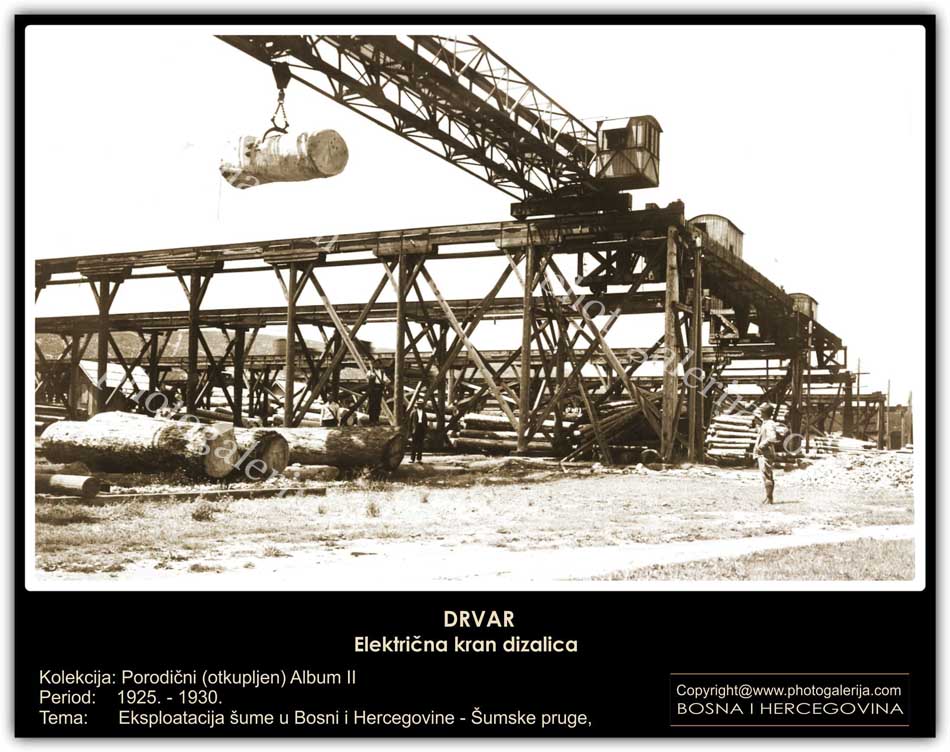

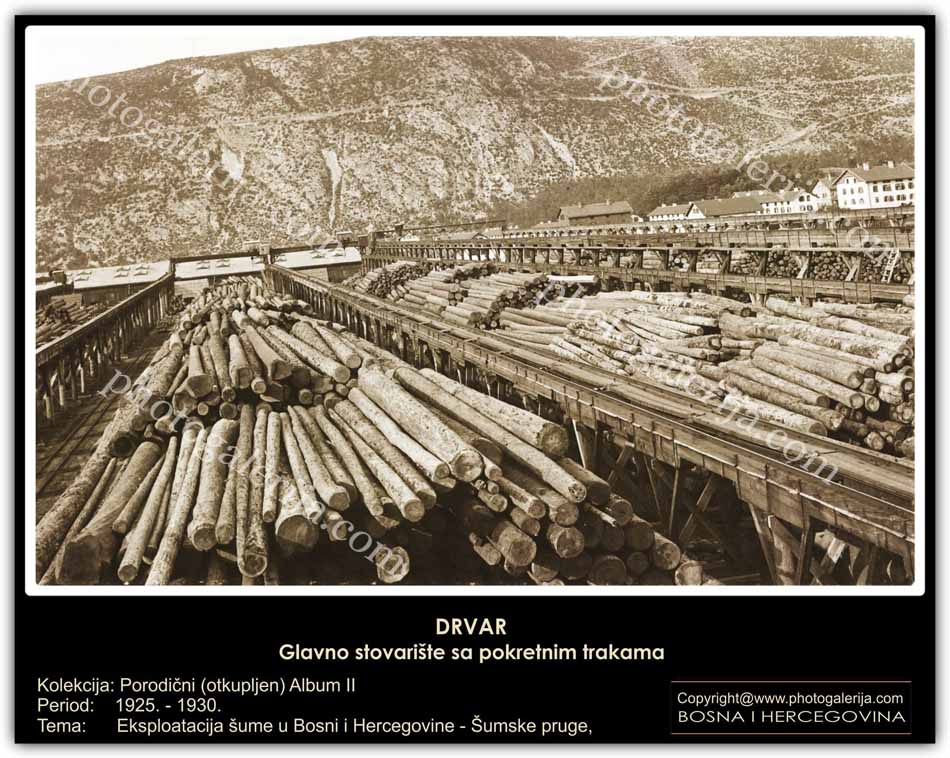

Regarding the exploitation of beech and oak forests for the purpose of producing railway ties, the primary logging activities are directed towards forest complexes: Gremč, Montenegro, Šator, Vijenac, Risovac, Plješevića, Pastrijevo, Šiša, Palež, Čemernica, and Manjača in the western part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Additionally, Prosara, Motajica, Vučjak, Ozren, Konjuh, Usora, Nemila, Igman, Ivan Bičovnja, Donja Prača, and others in the northern and central parts of Bosnia, specifically in the Sarajevo region. A study for opening these forest complexes raised the issue of access to exploit these forests. Many forest advisors (of foreign origin) worked on overcoming transportation obstacles for the wood mass to public roads, and their evaluations and proposals were based on the use of wire railways (cable cars), cranes, and the construction of forest railway lines that would transport the timber down into the river valleys, specifically to the watercourses of the Drina, Ribnik, Sanica, and Sana rivers by rafting to sawmill facilities. It is indeed confirmed that under Austro-Hungarian administration, led by the Provincial Government, with the goal of utilizing the available natural resources through forest exploitation, they collected monetary revenues within the framework of “imposed” self-financing.

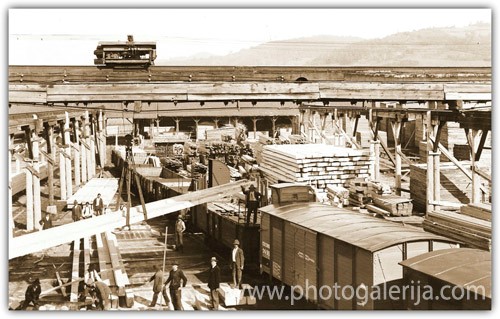

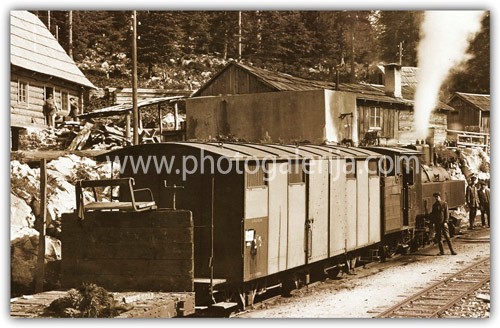

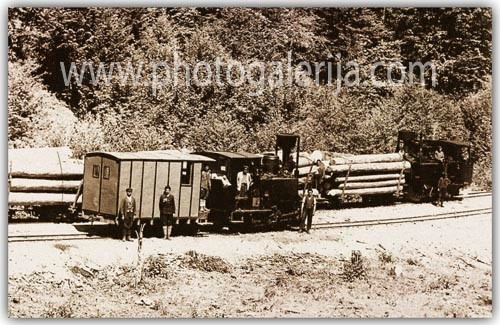

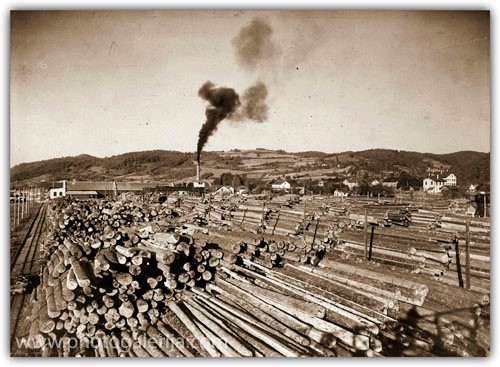

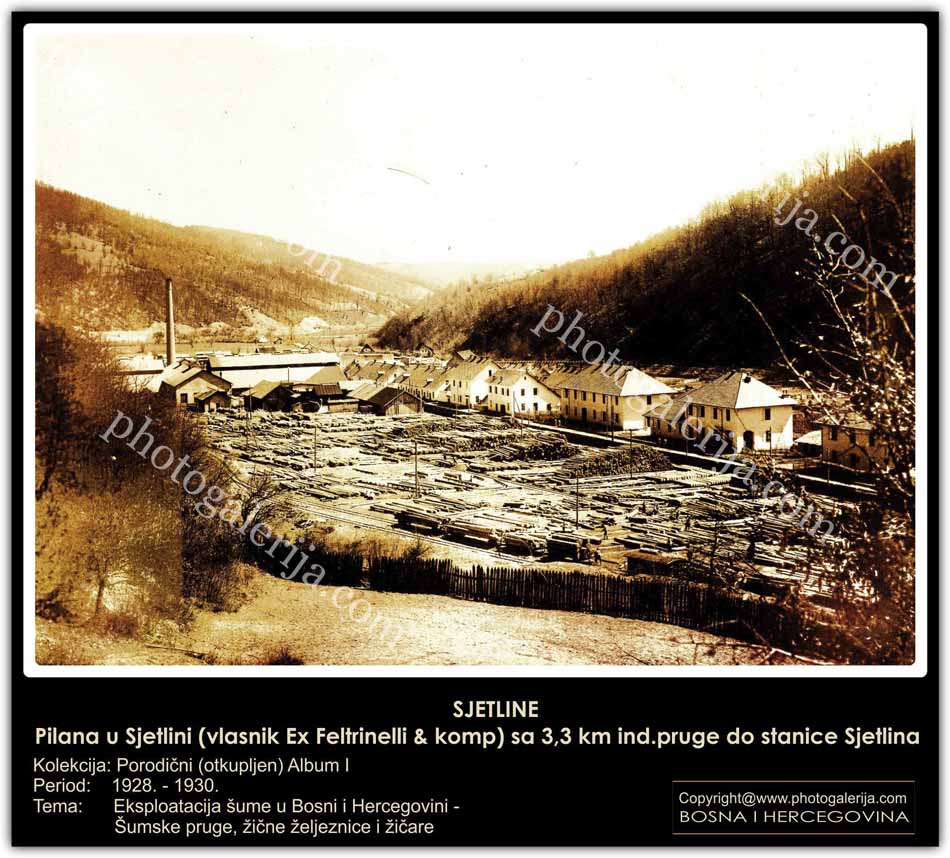

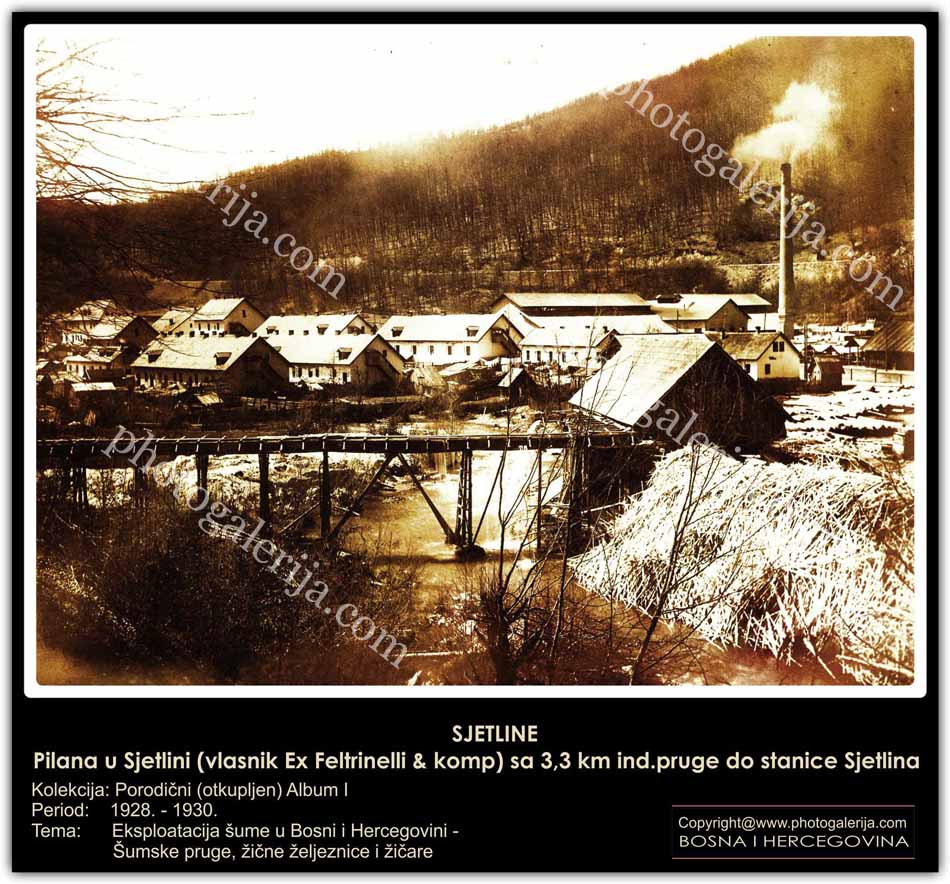

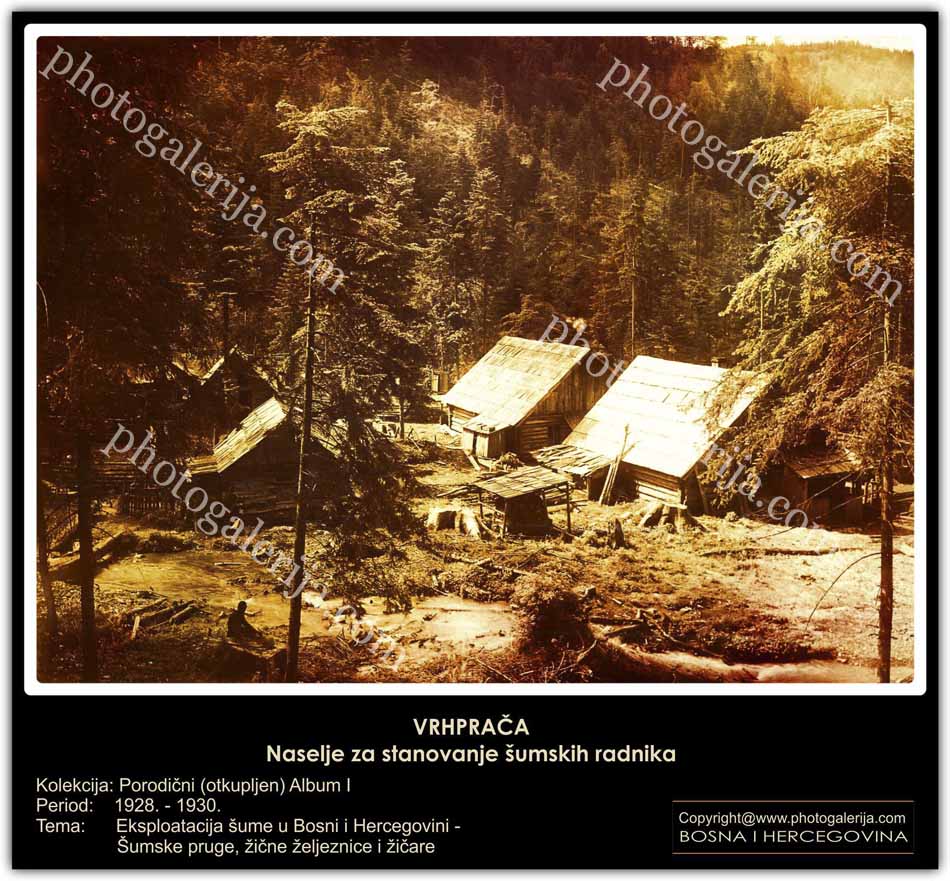

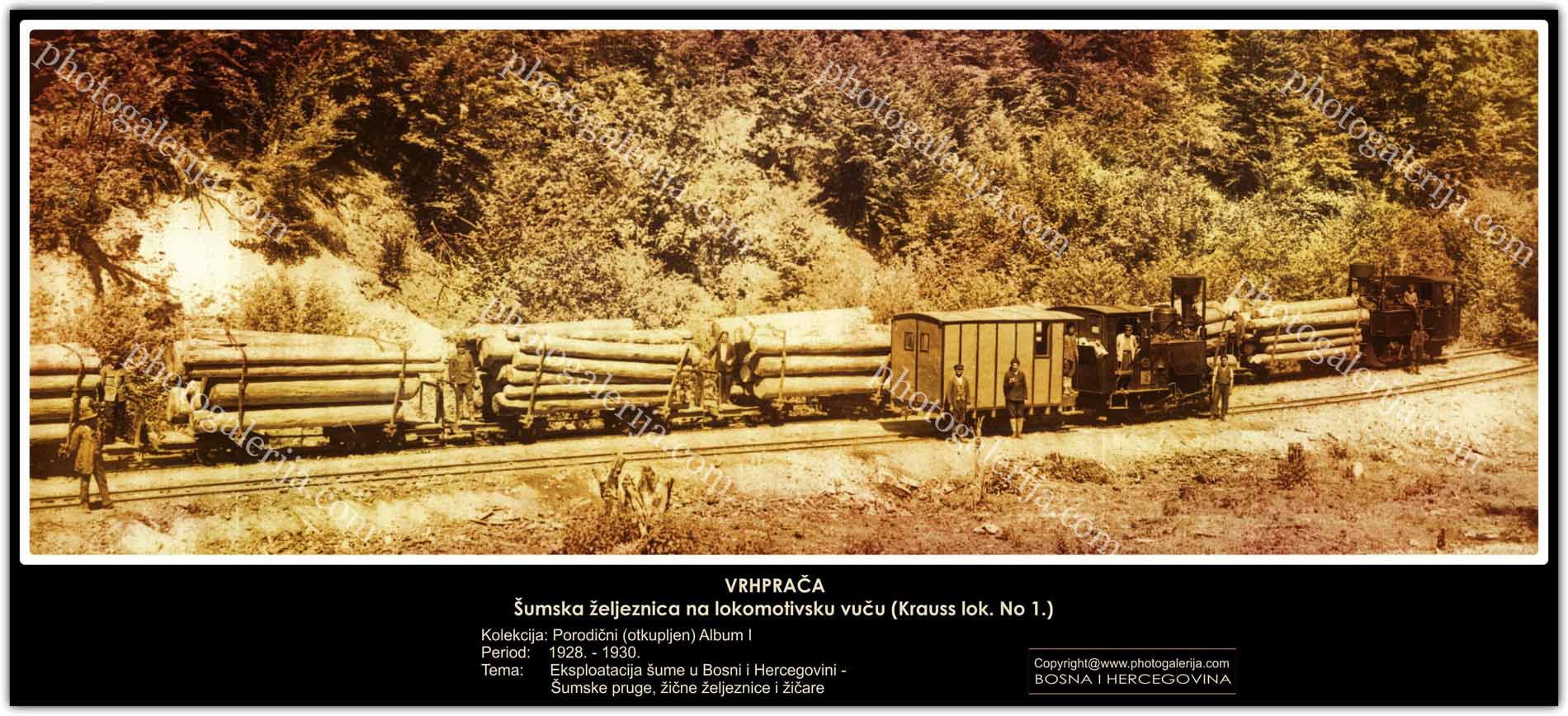

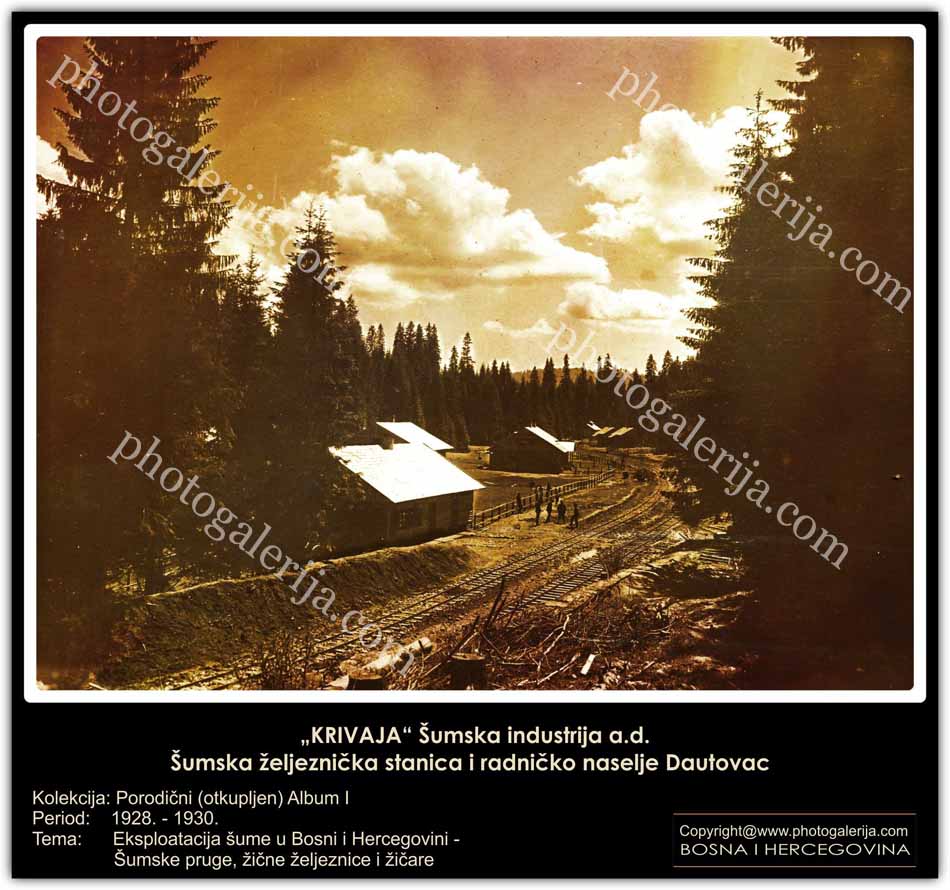

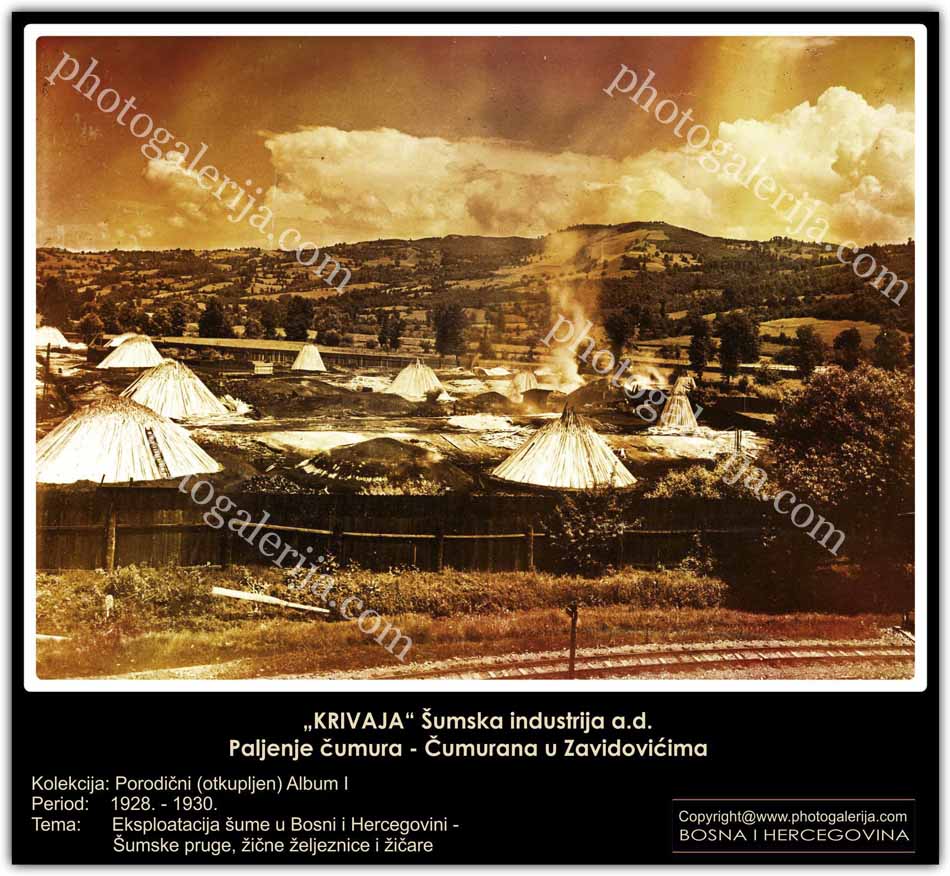

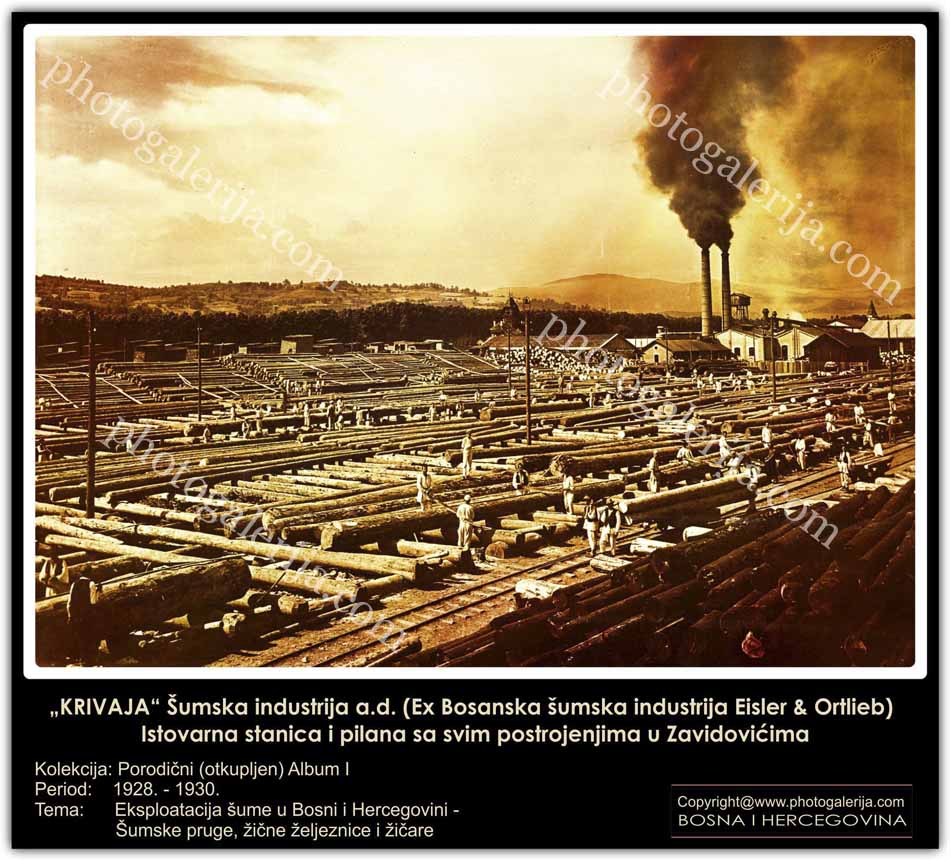

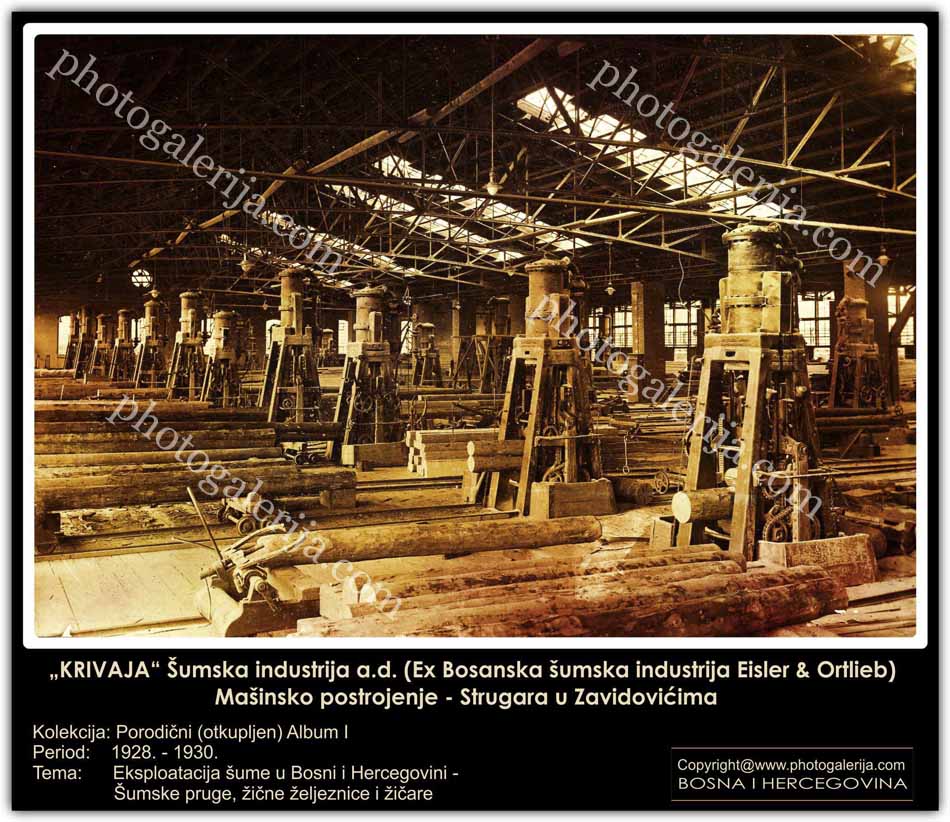

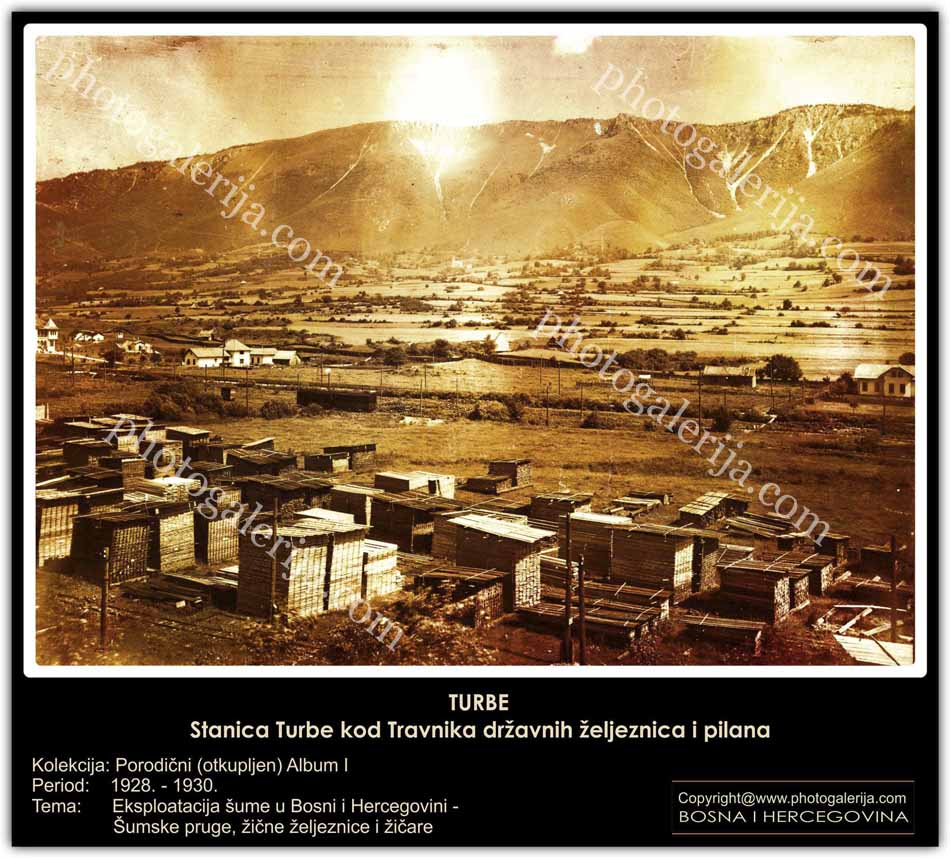

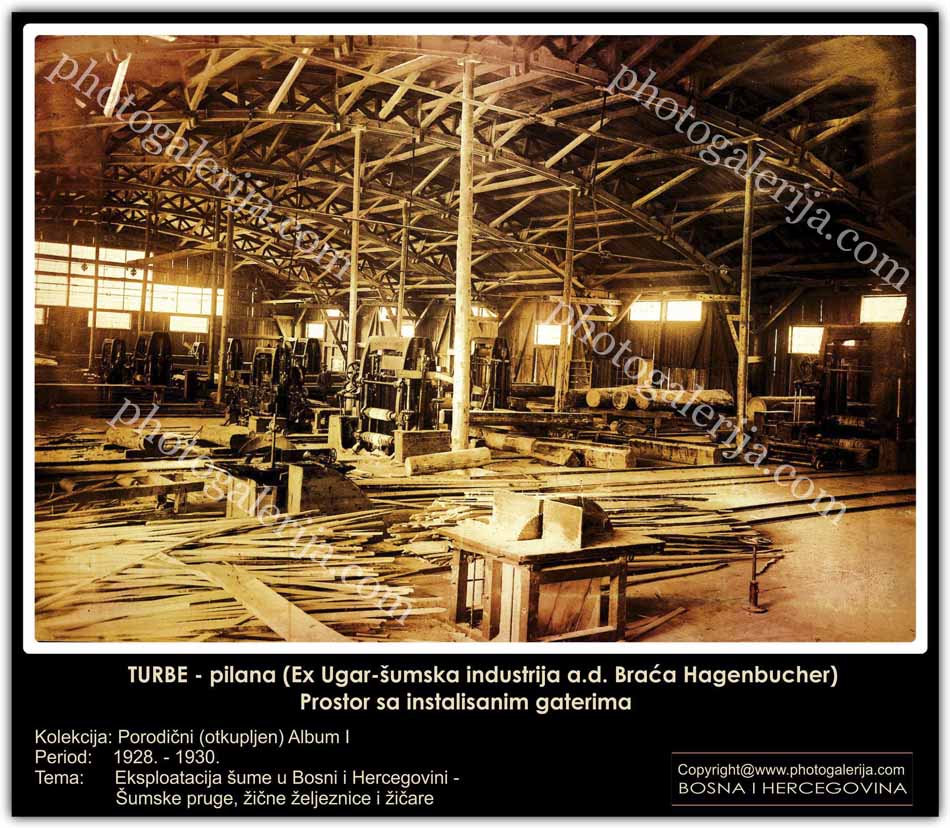

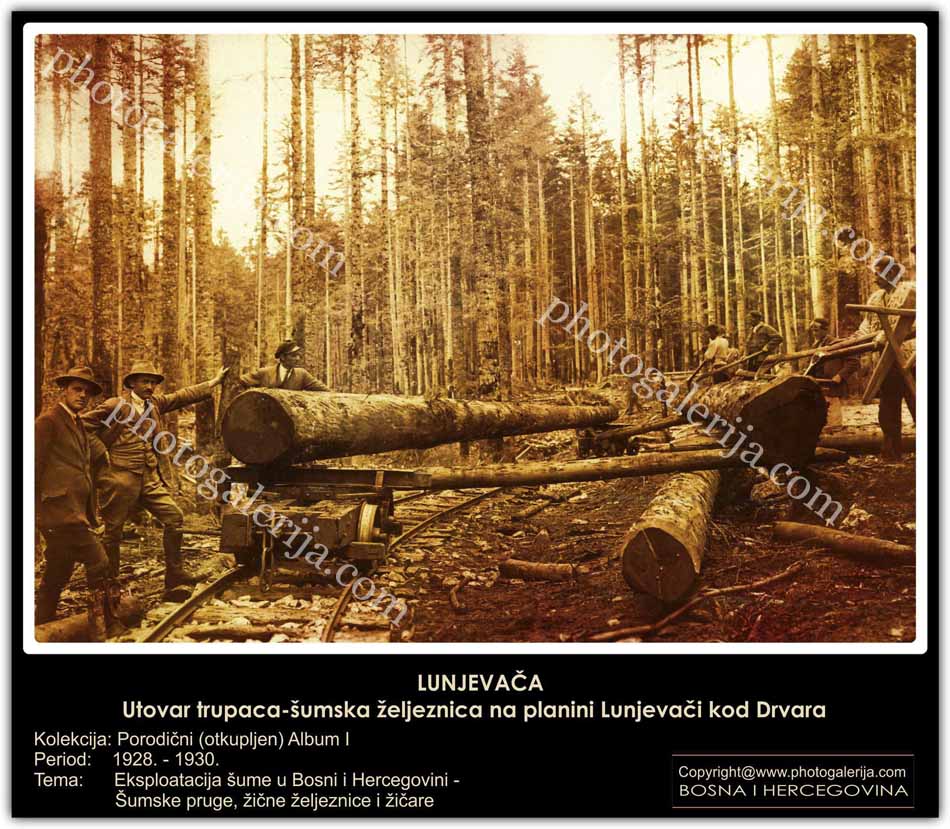

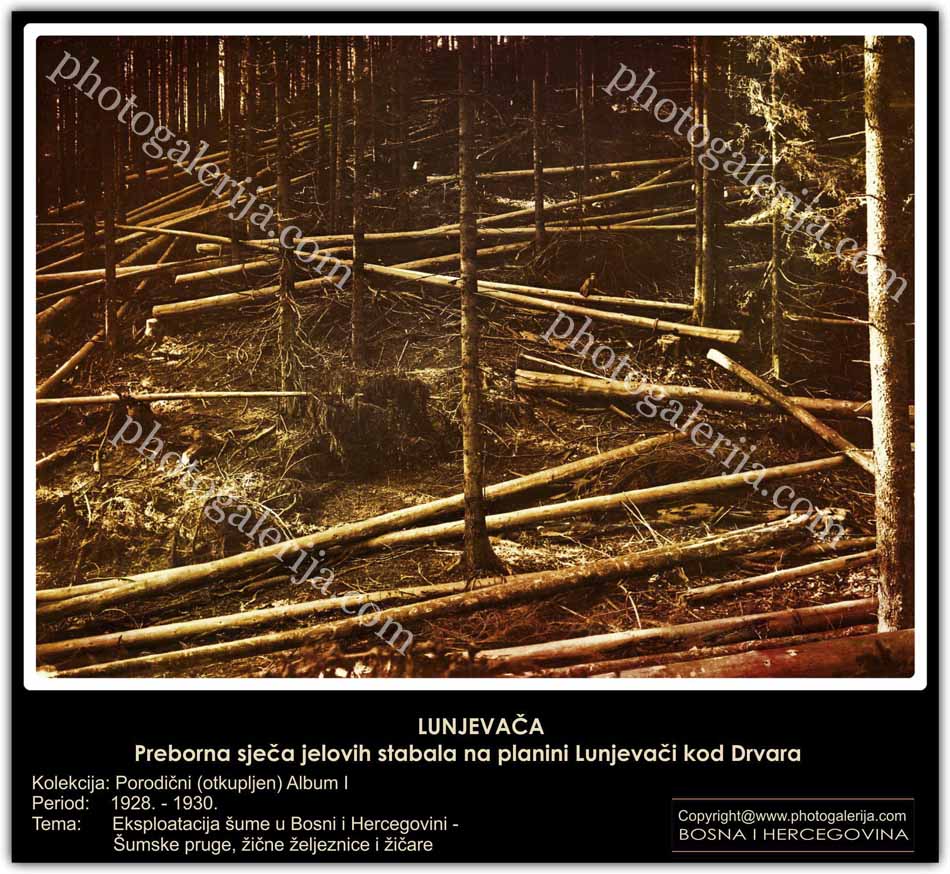

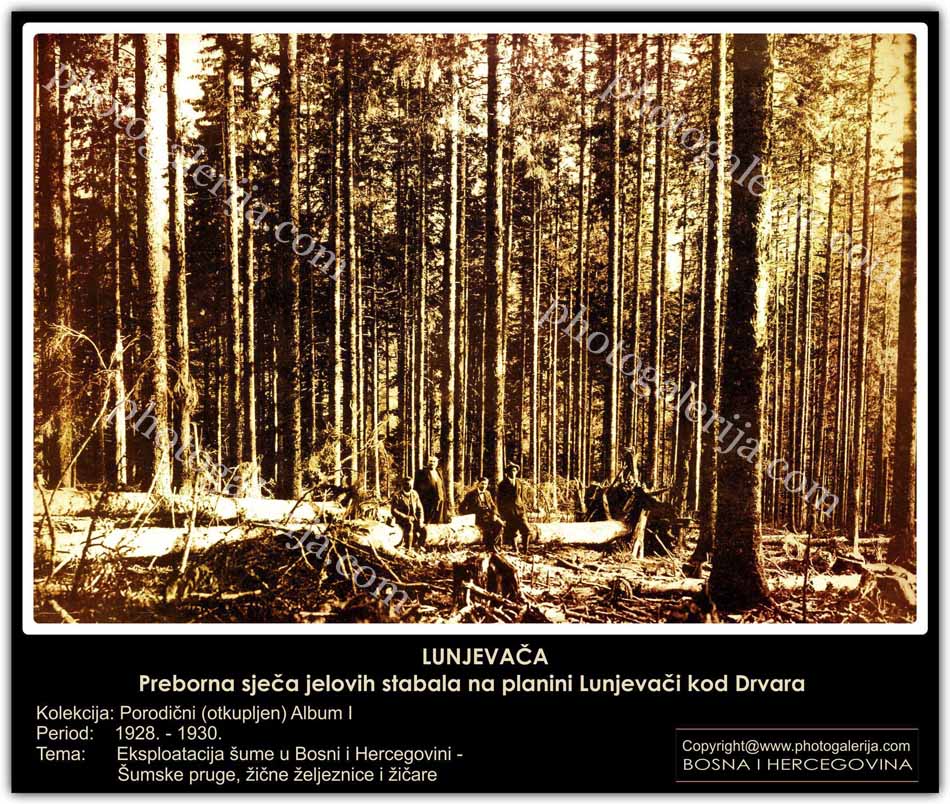

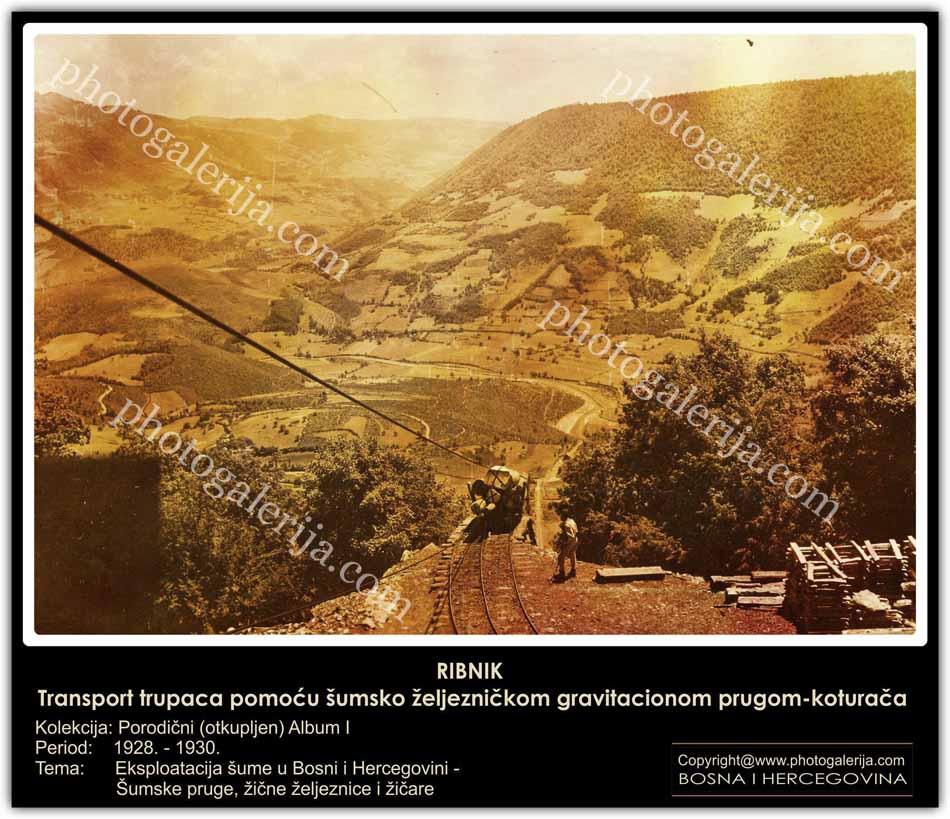

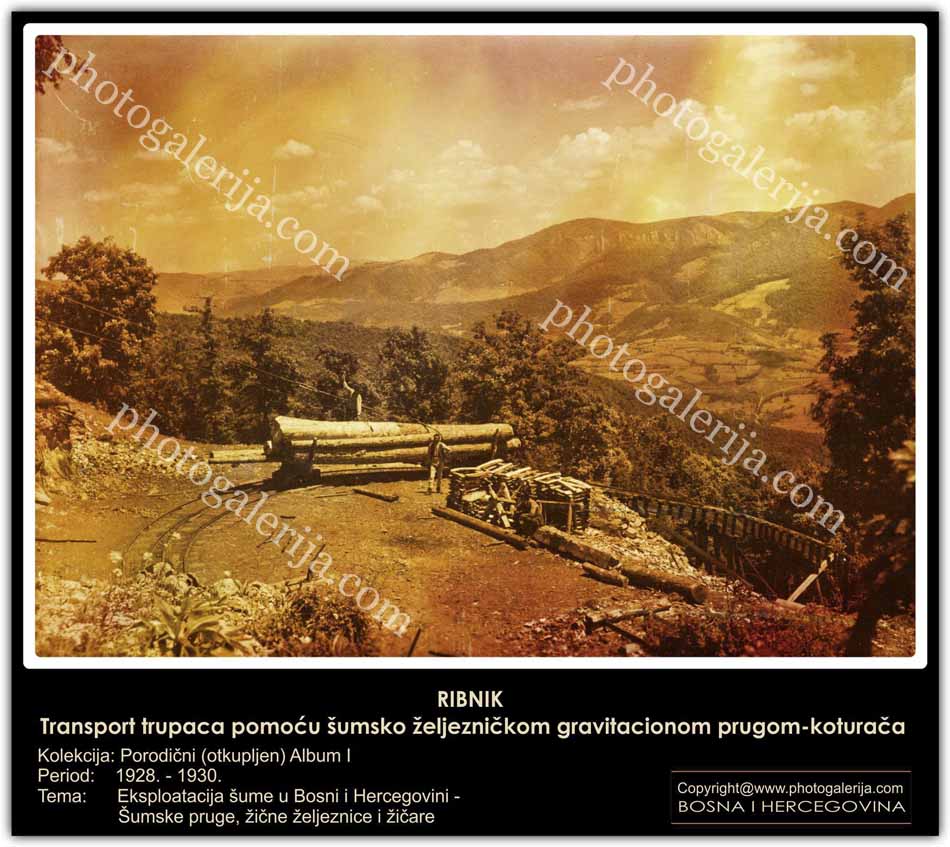

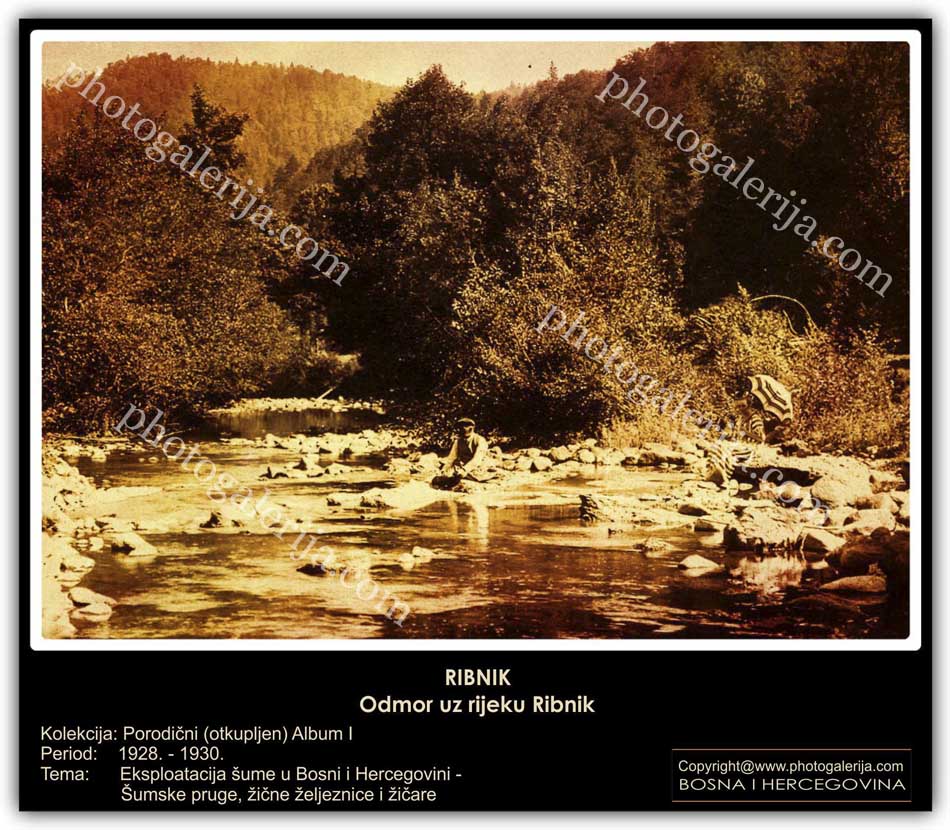

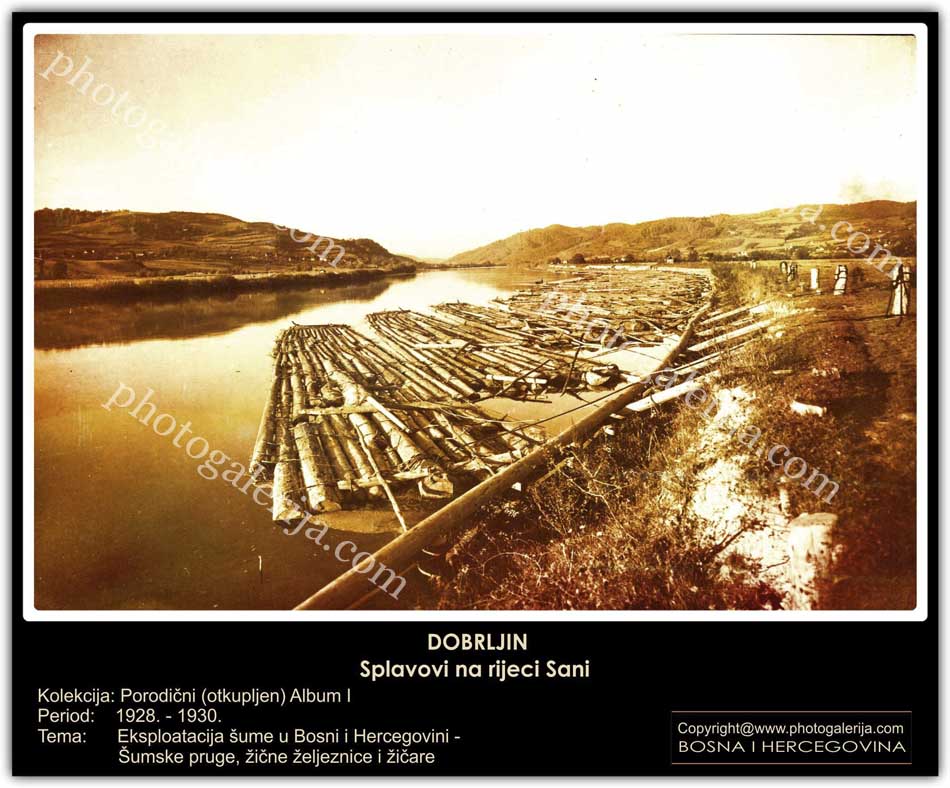

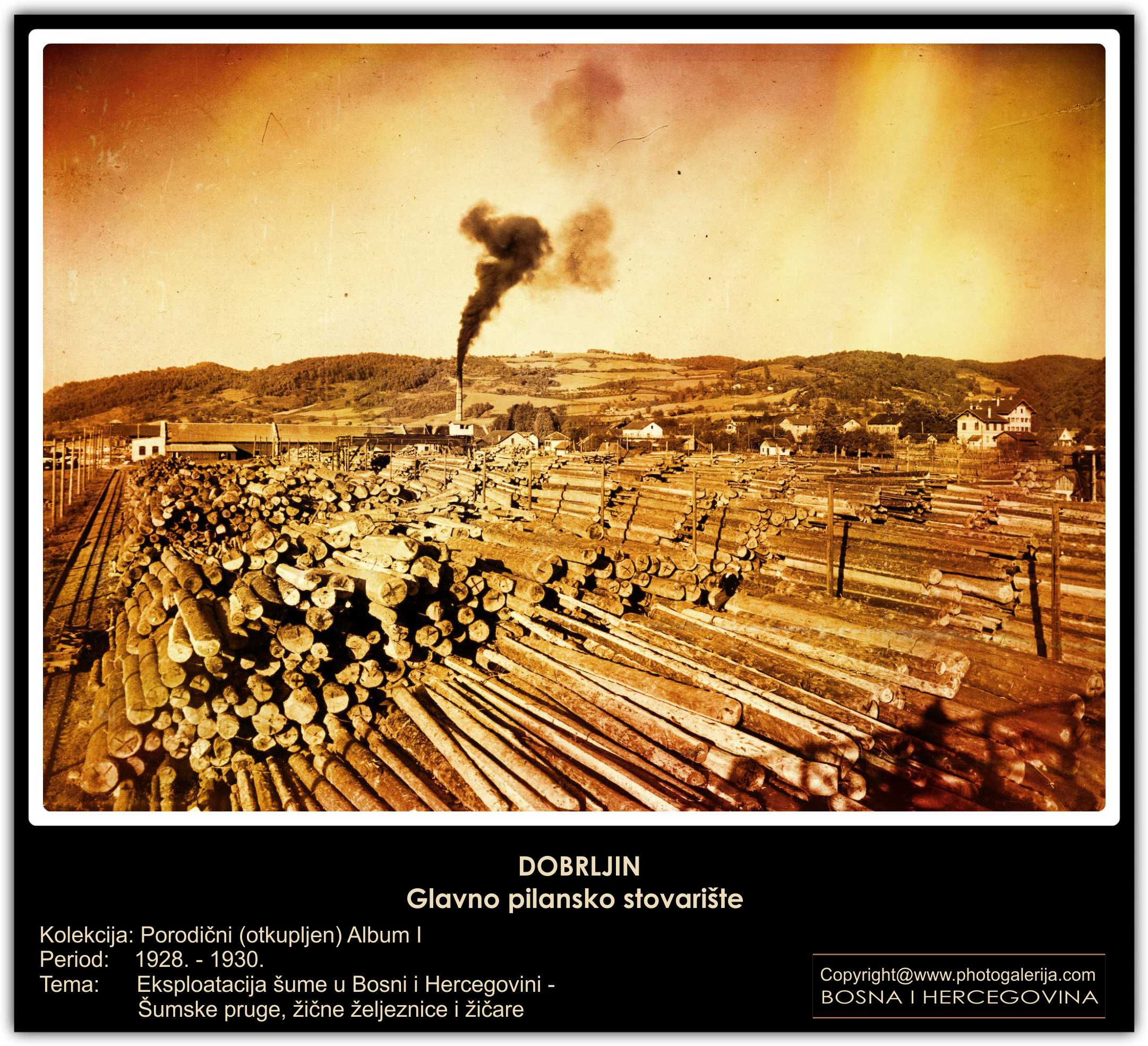

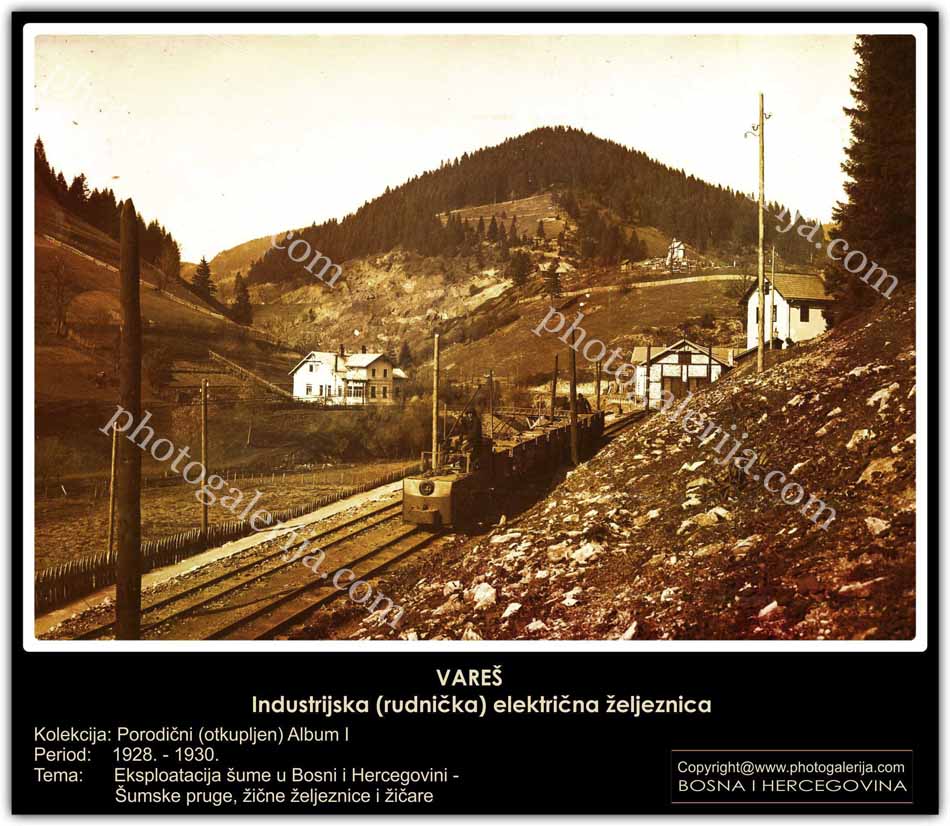

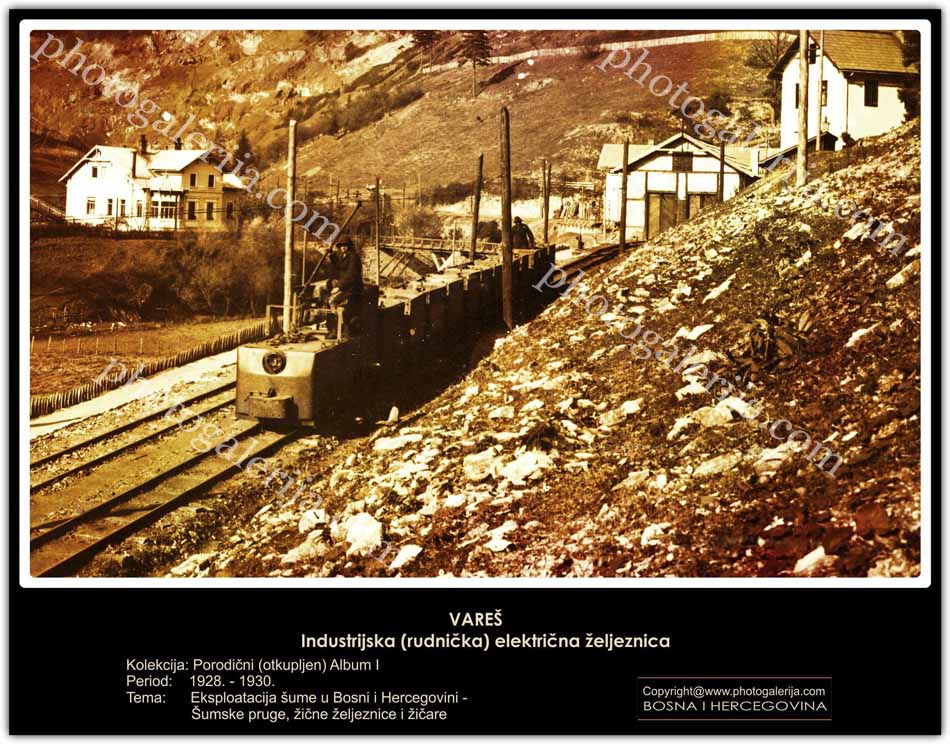

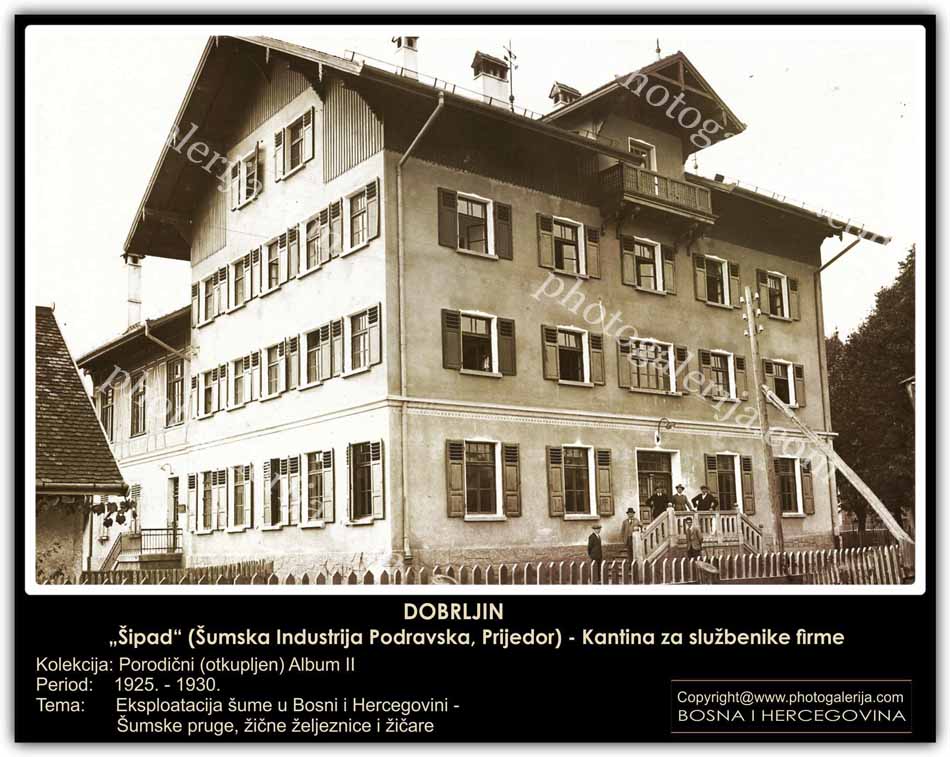

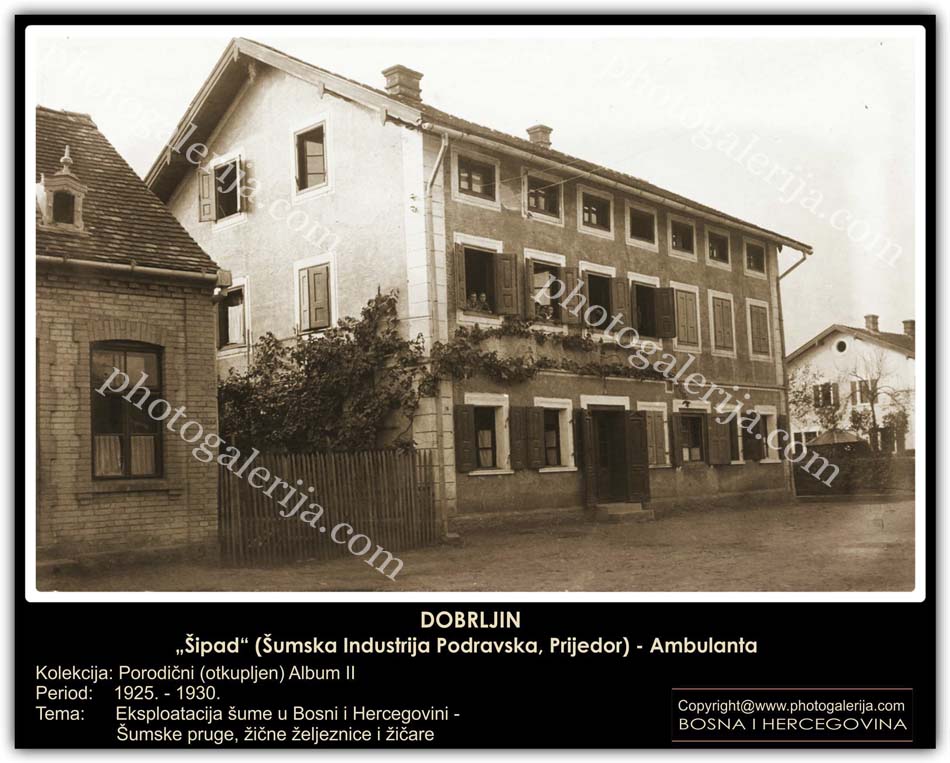

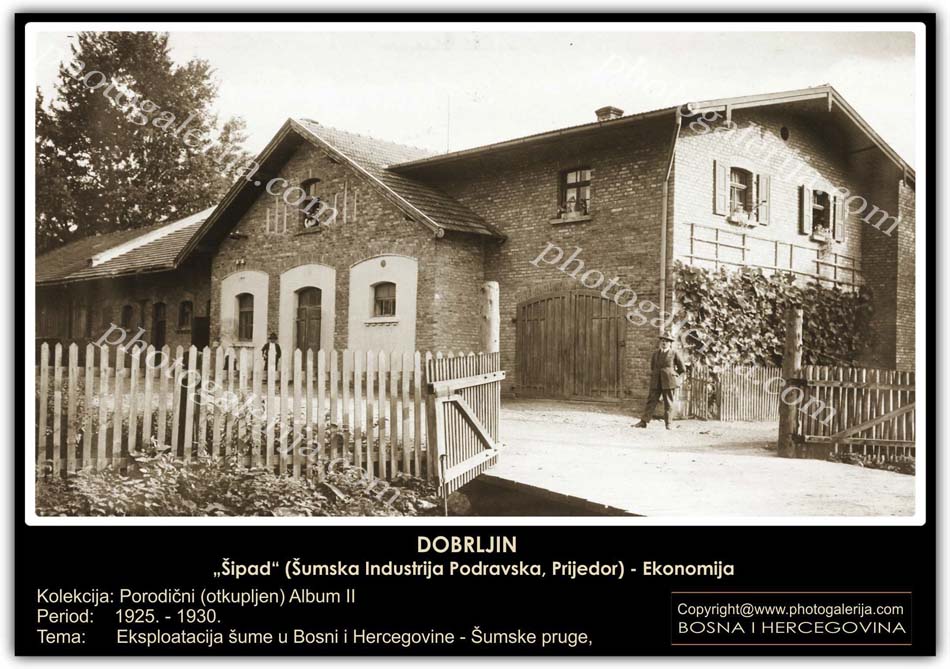

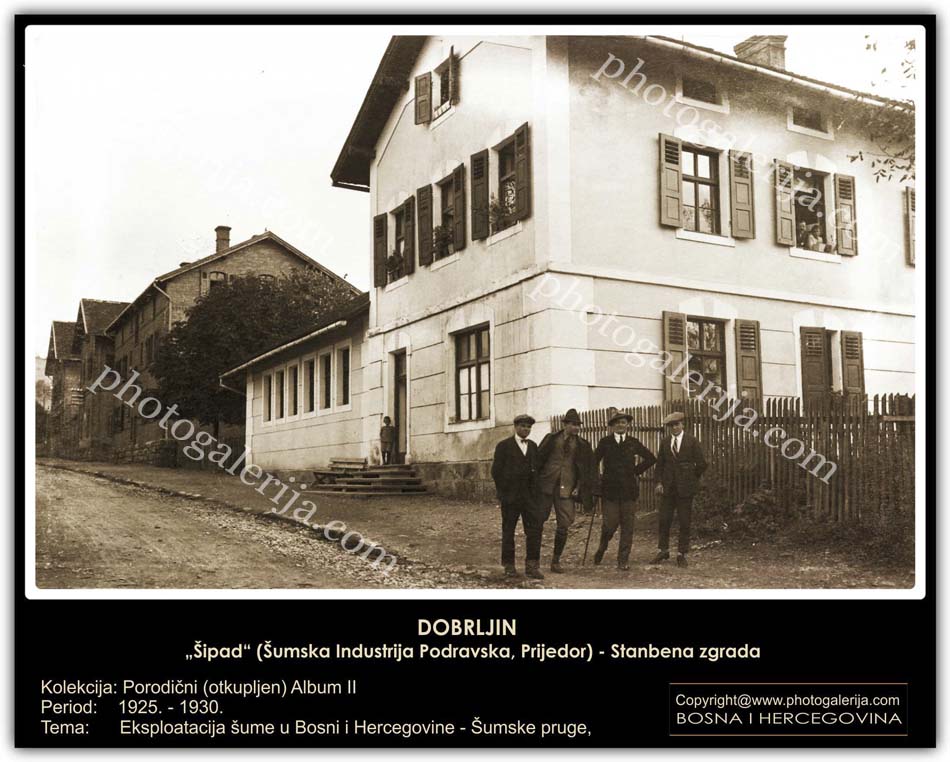

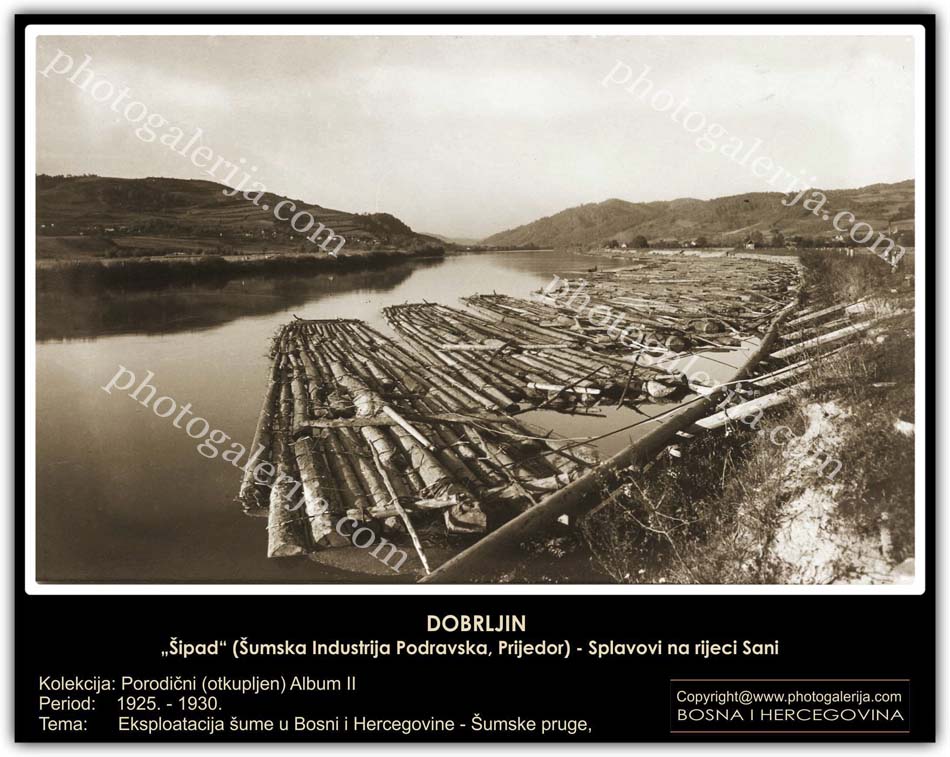

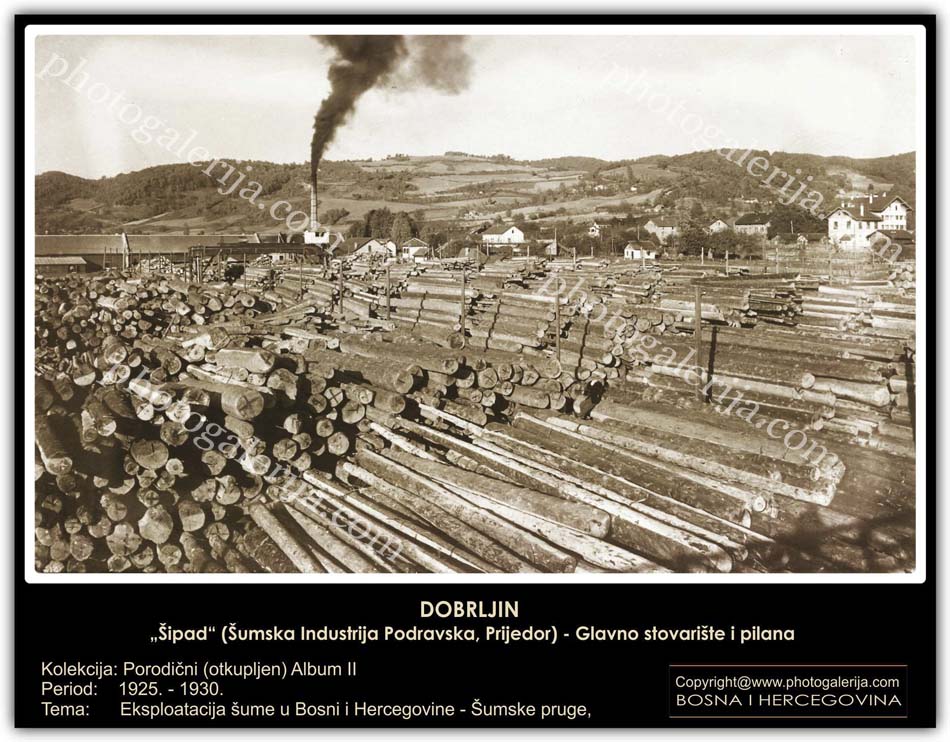

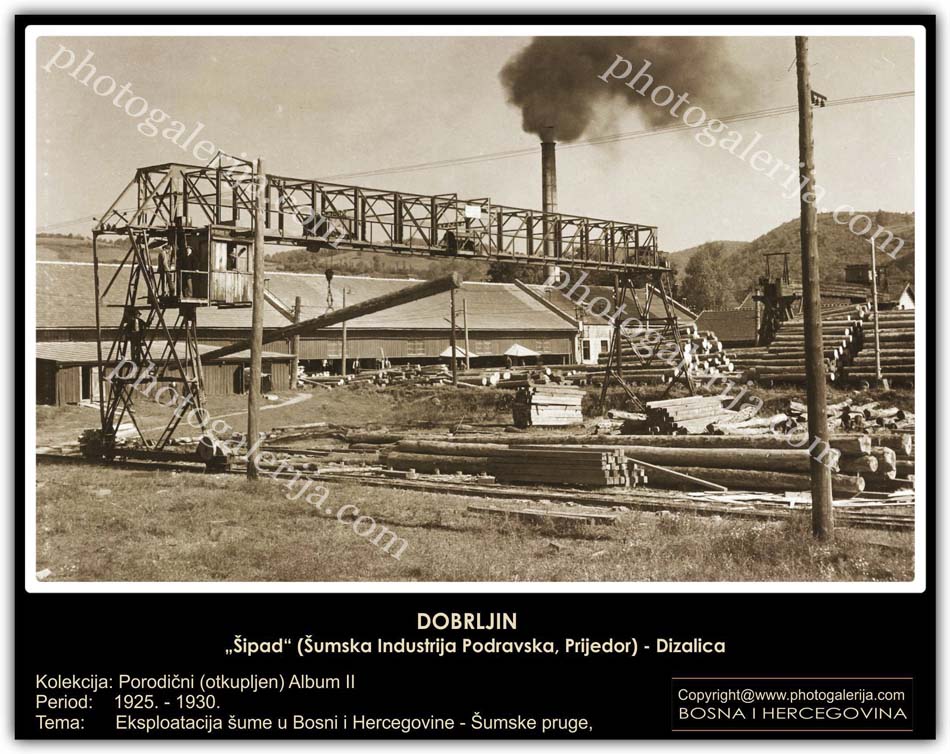

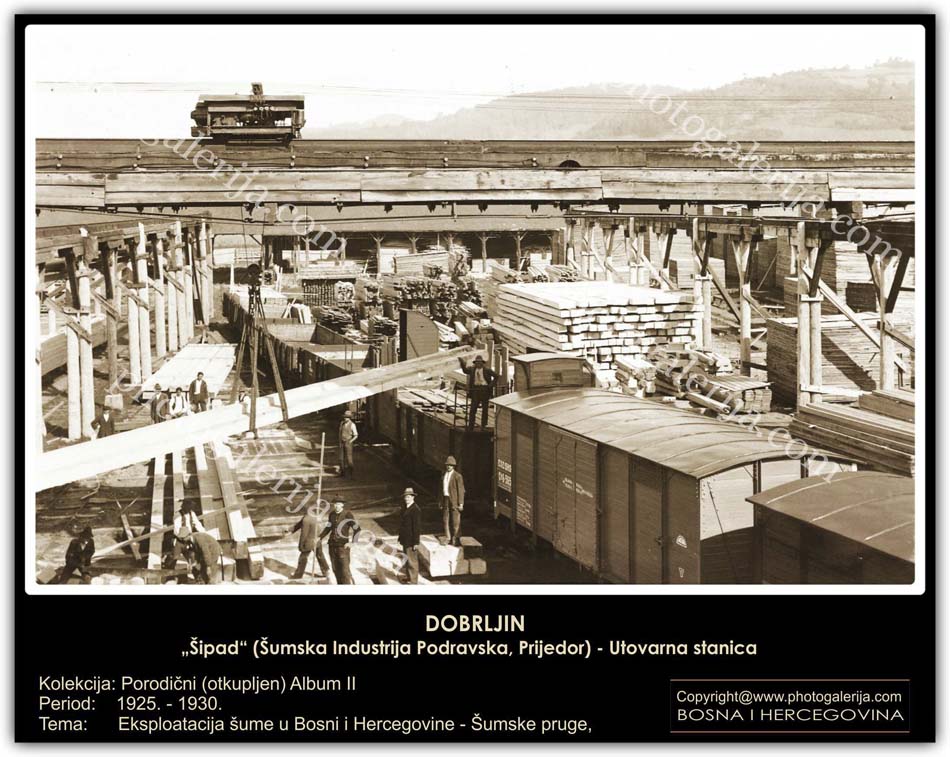

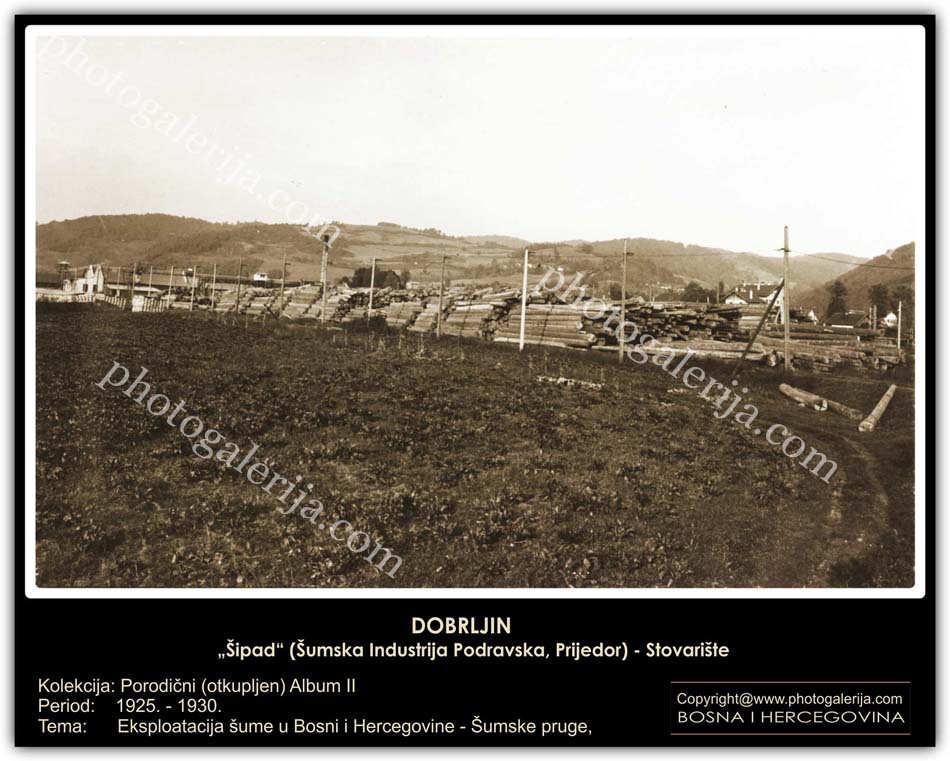

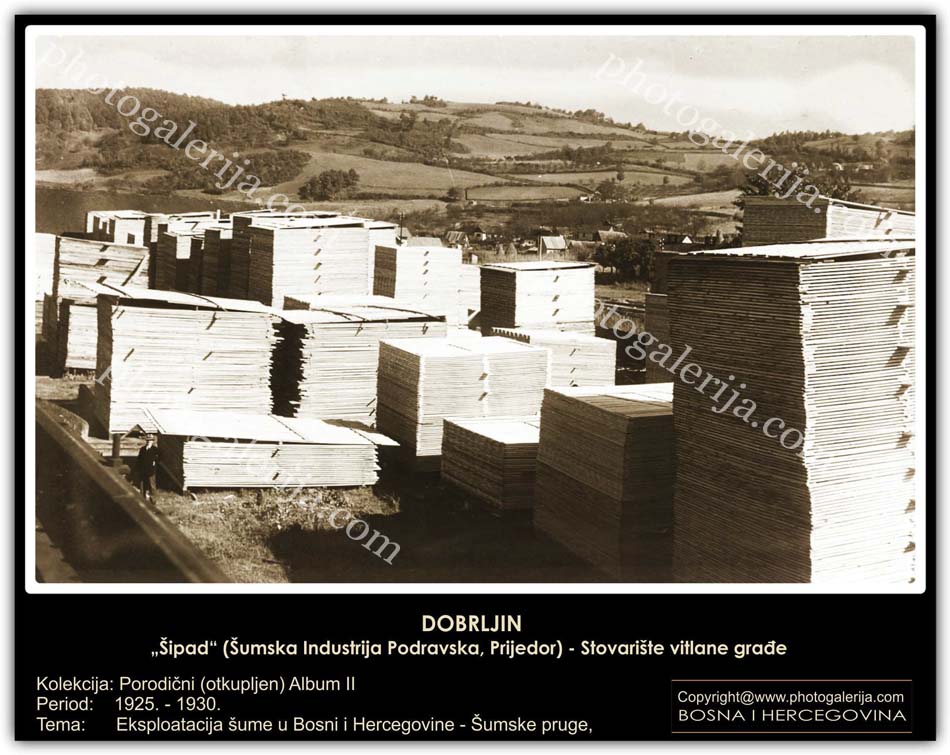

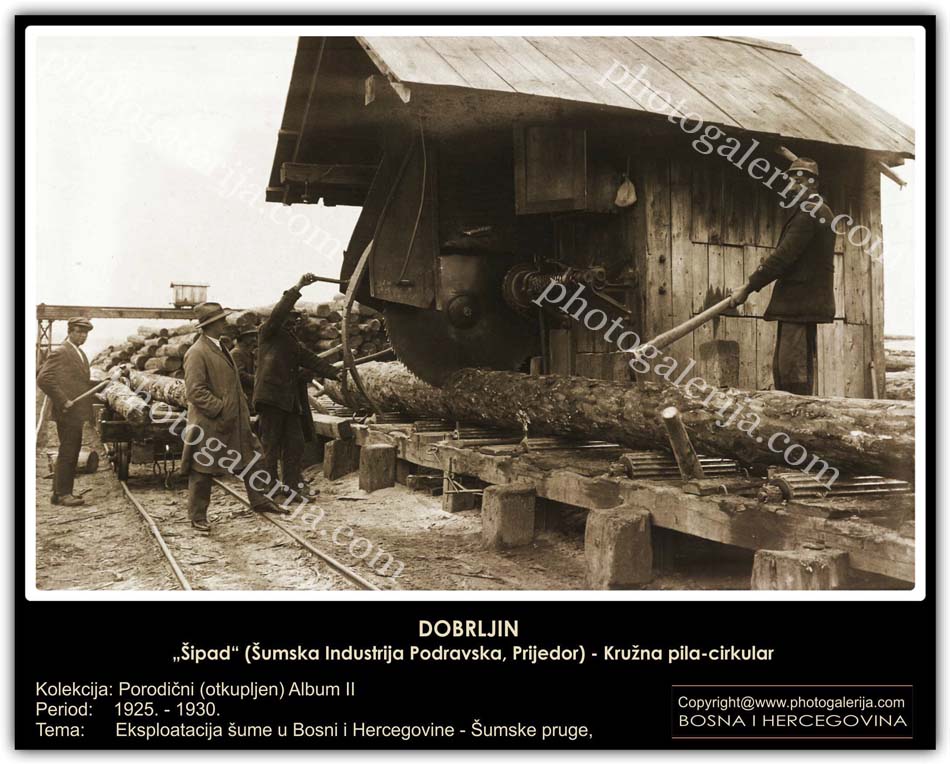

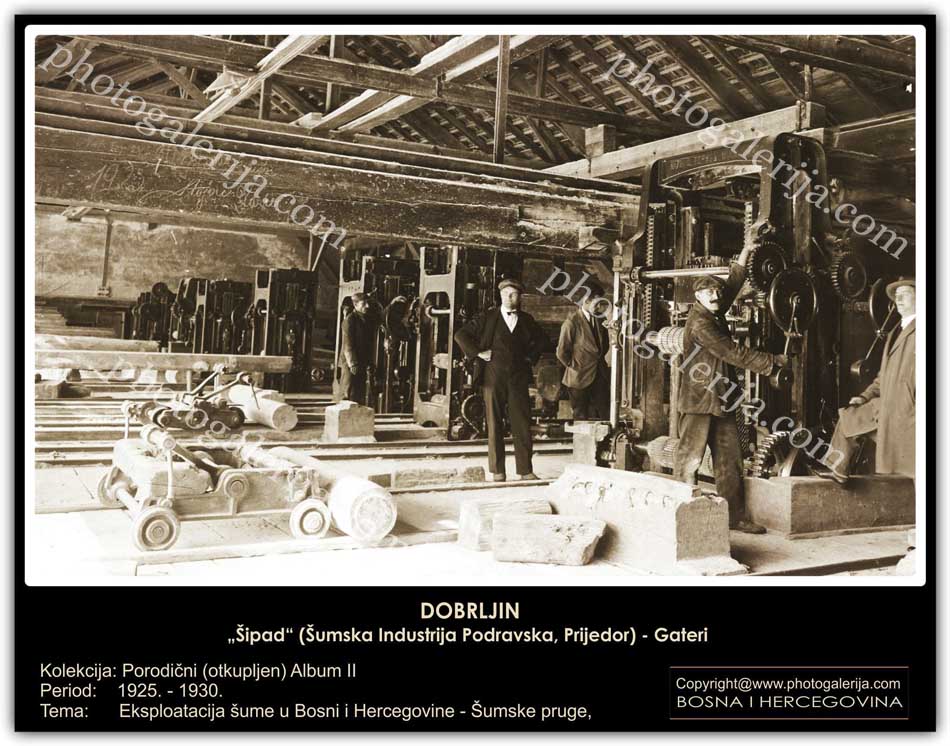

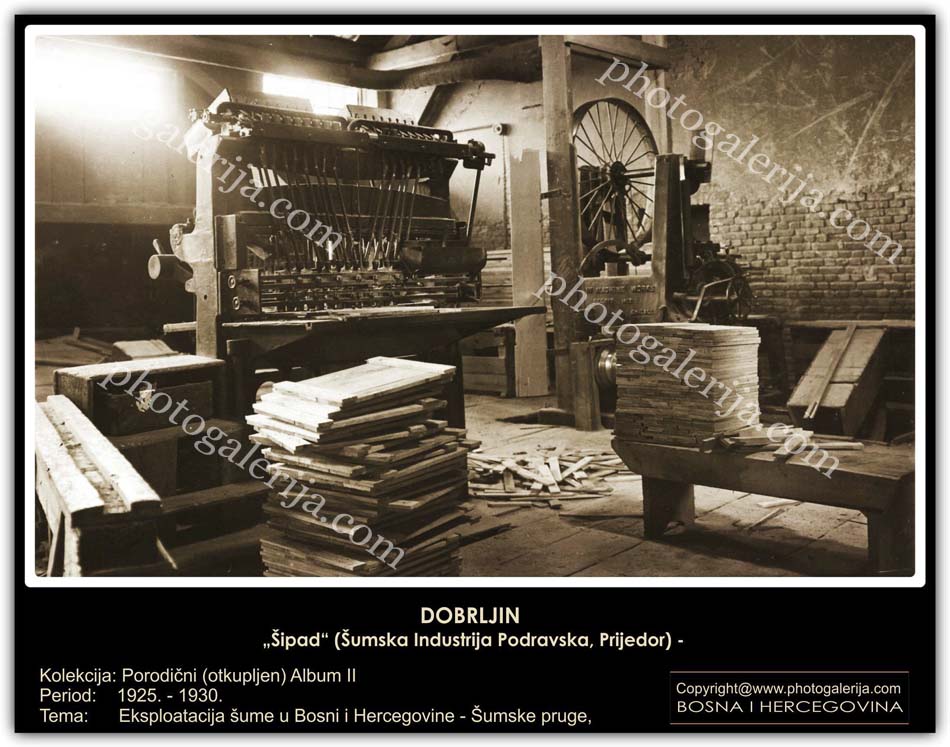

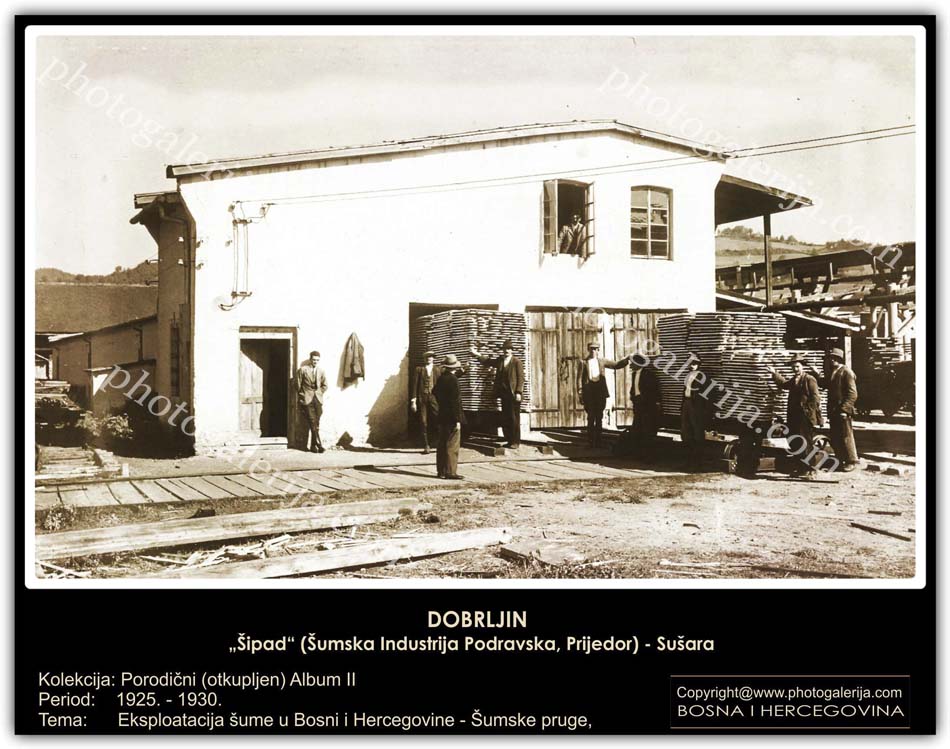

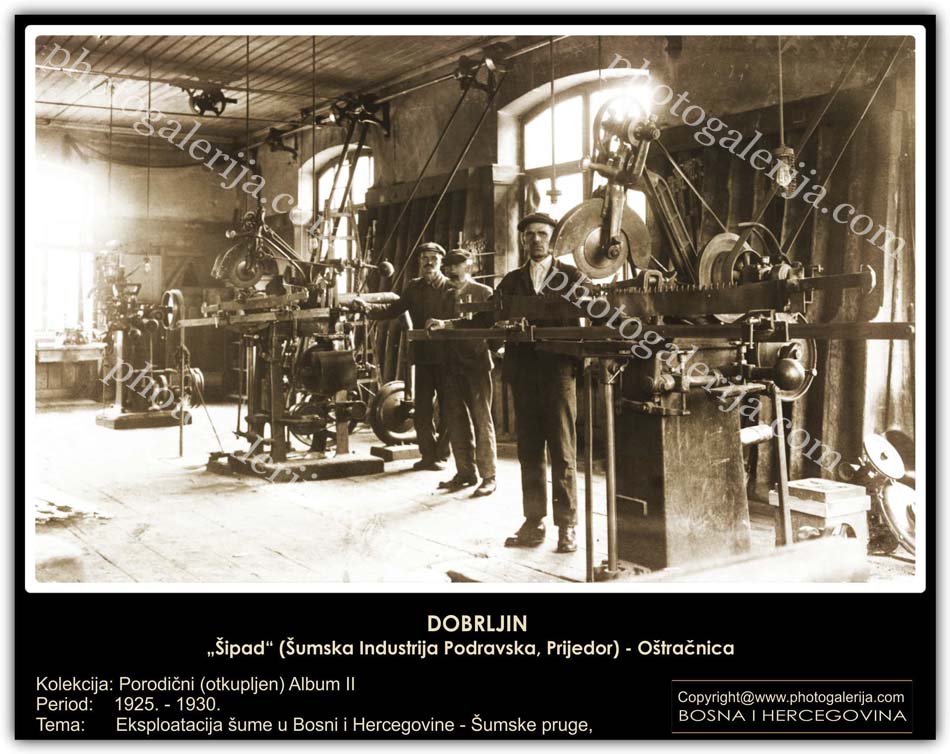

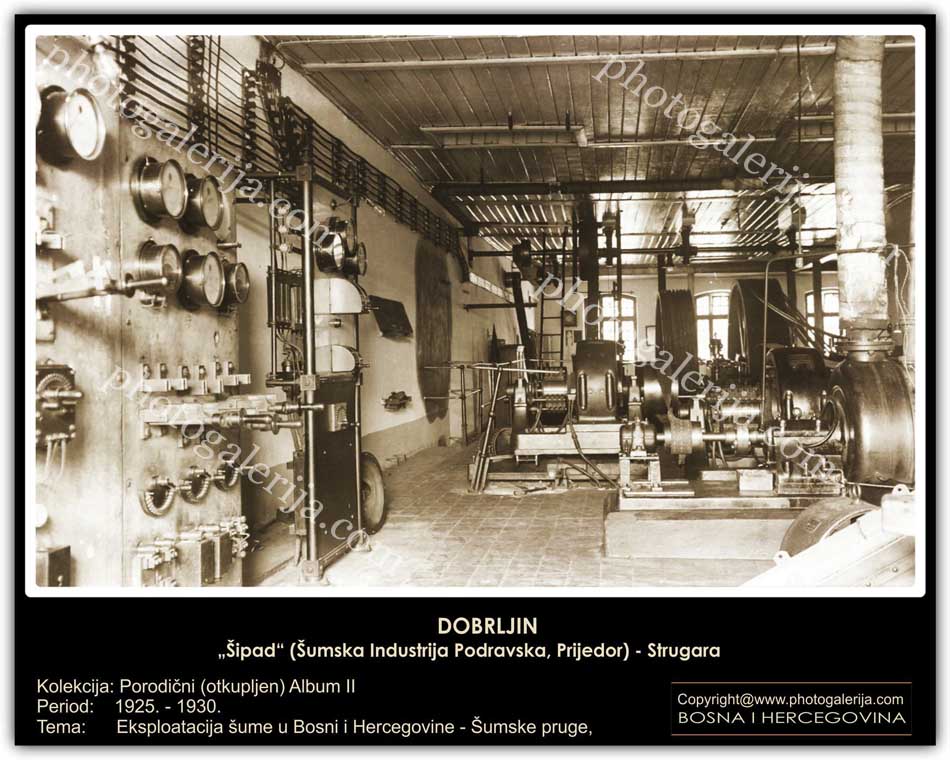

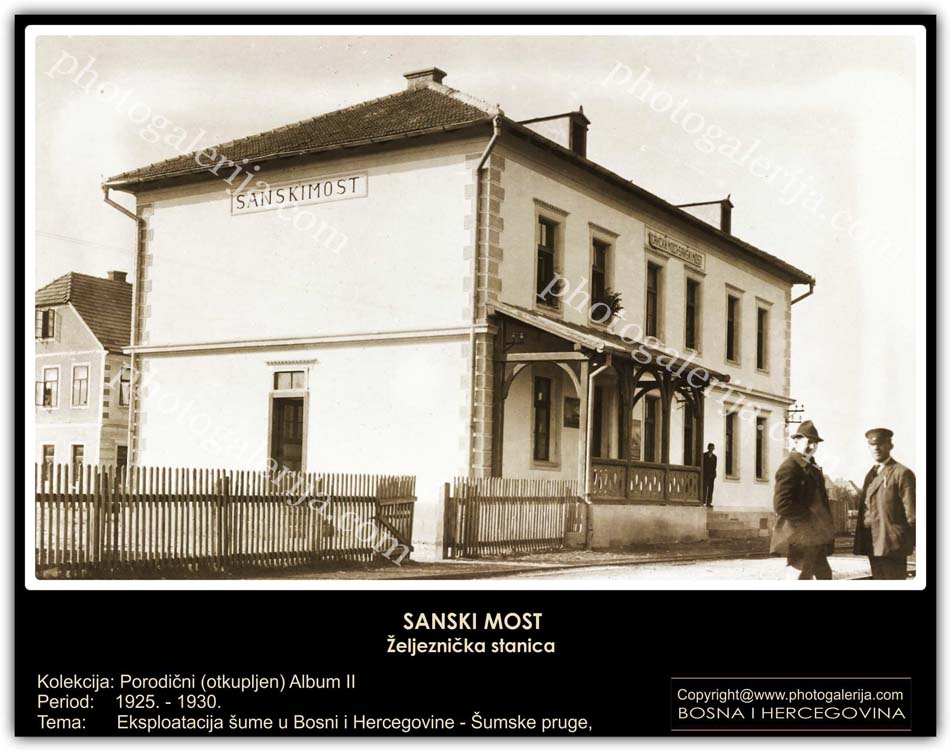

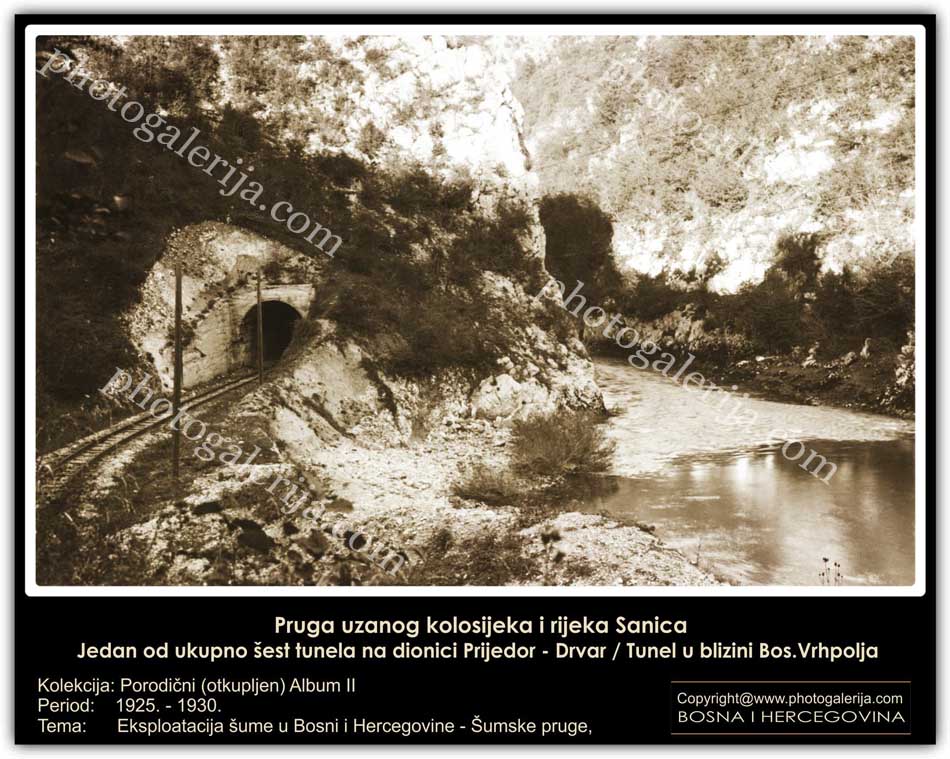

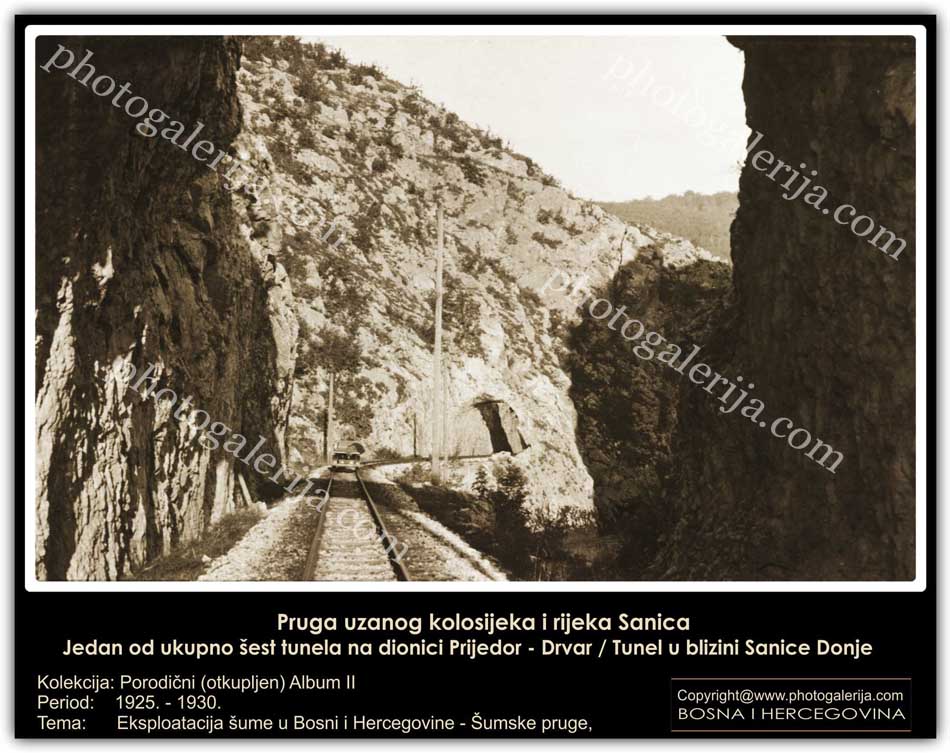

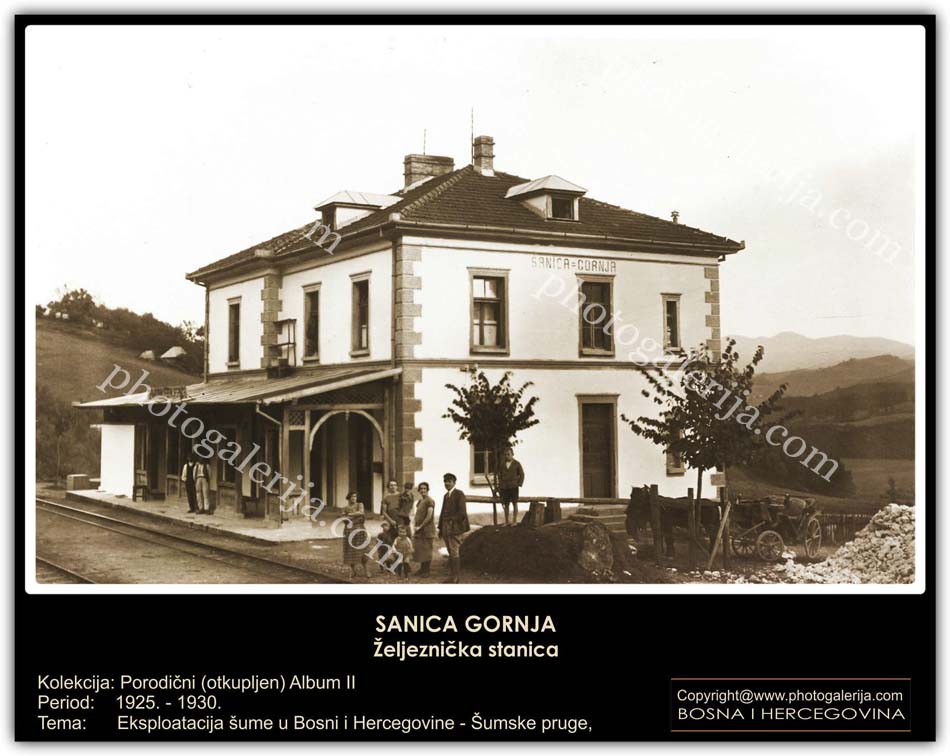

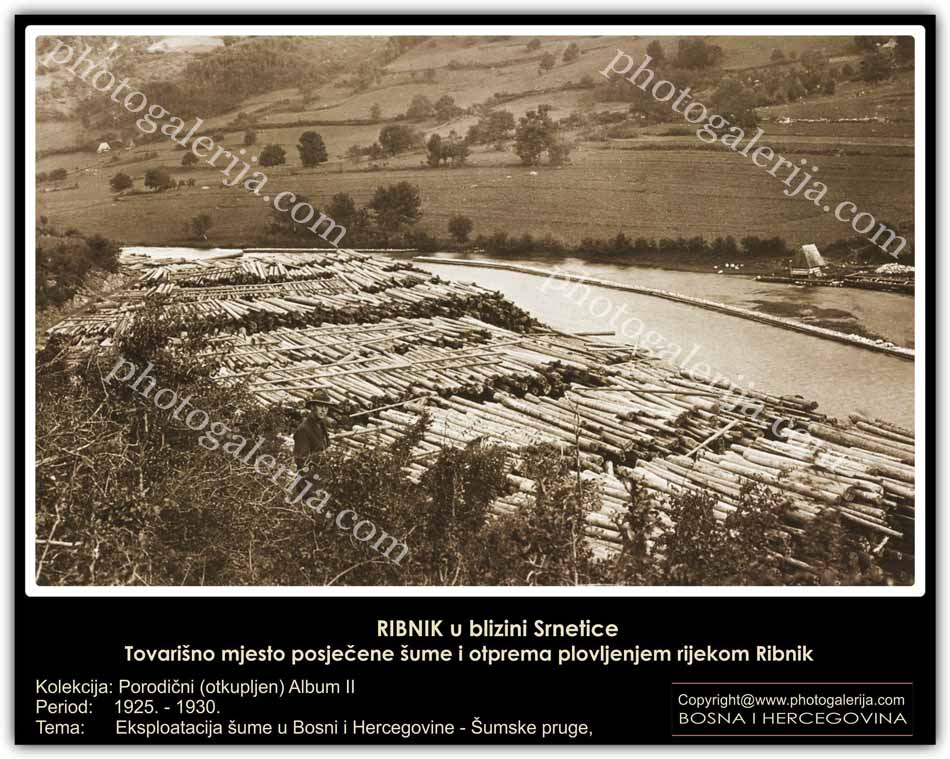

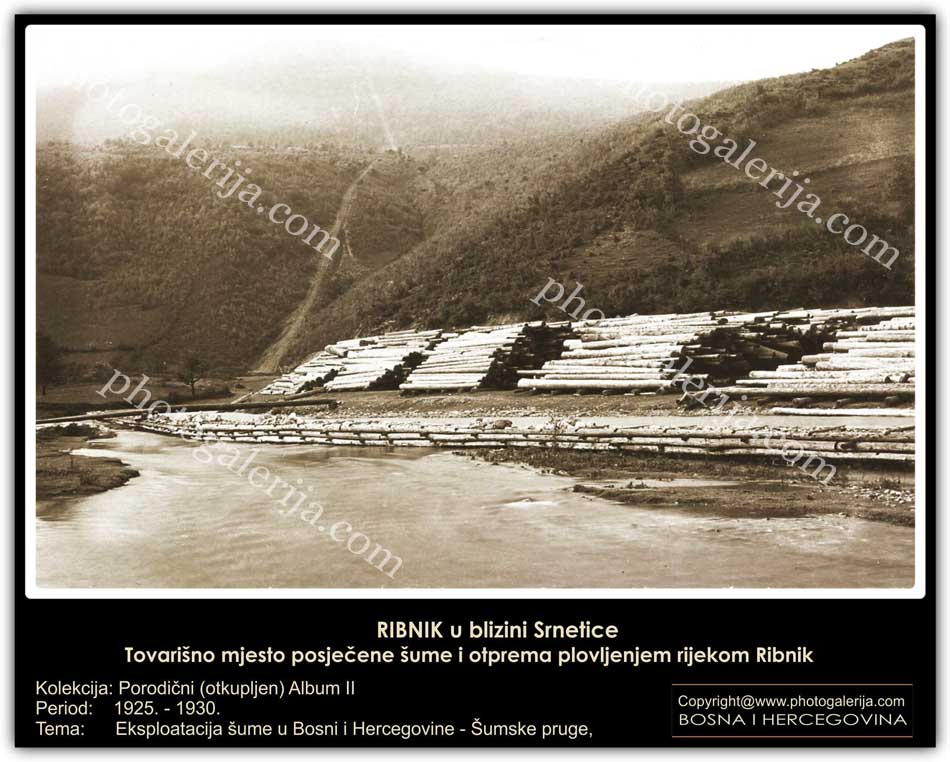

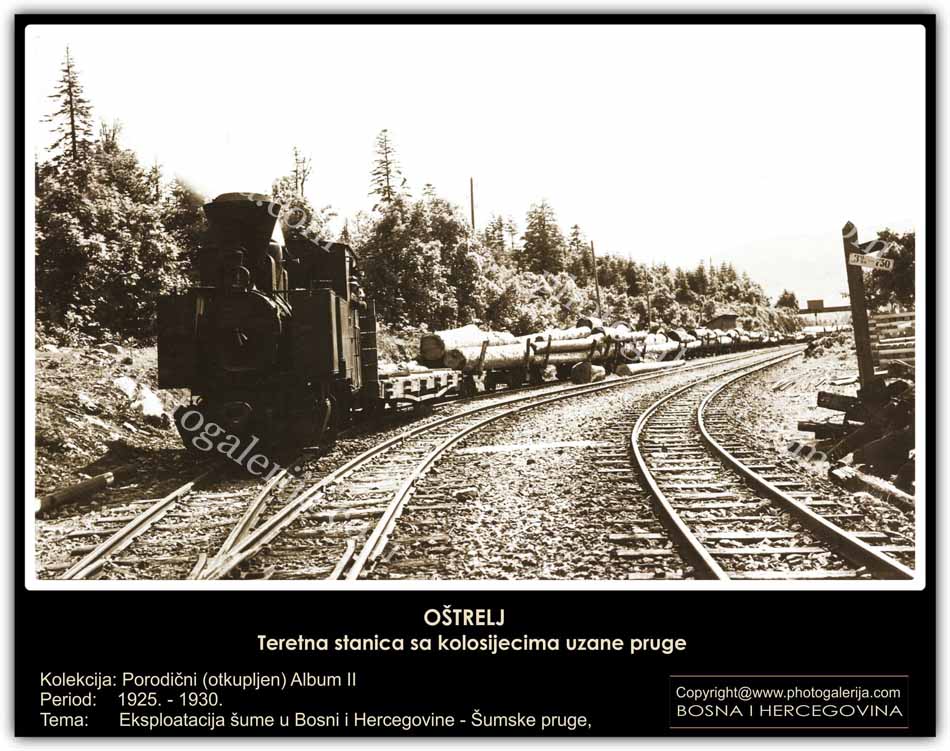

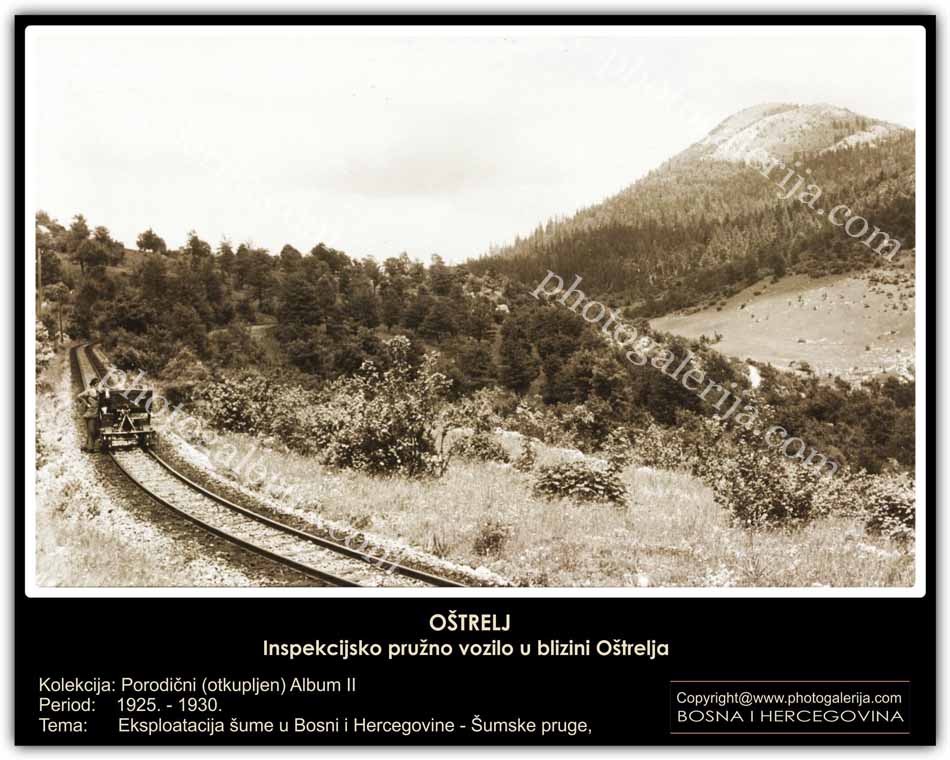

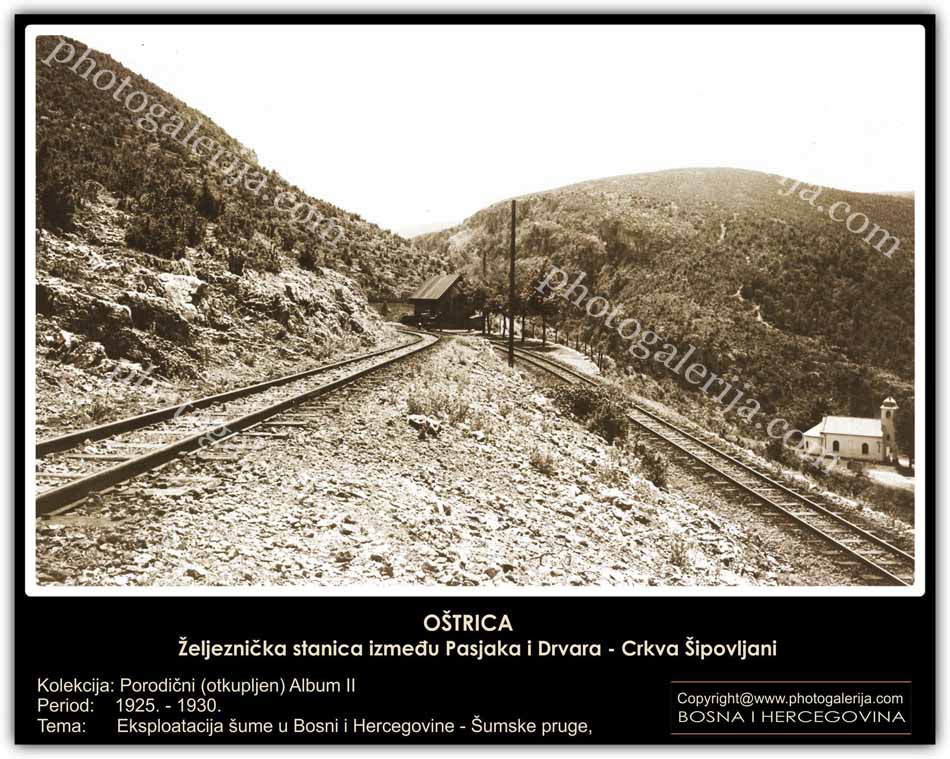

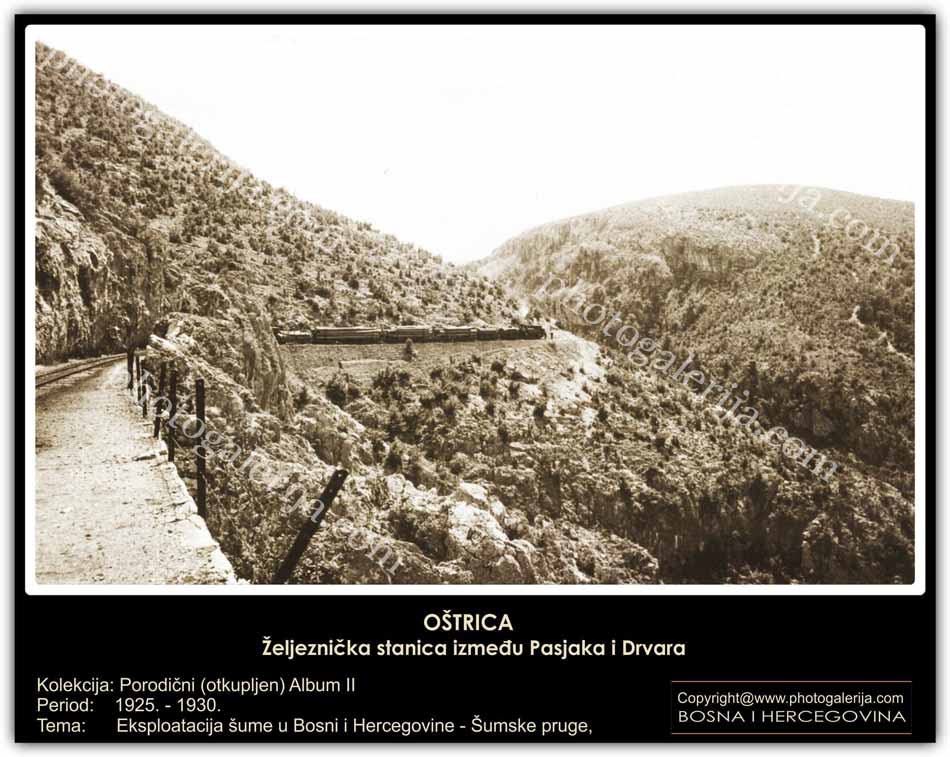

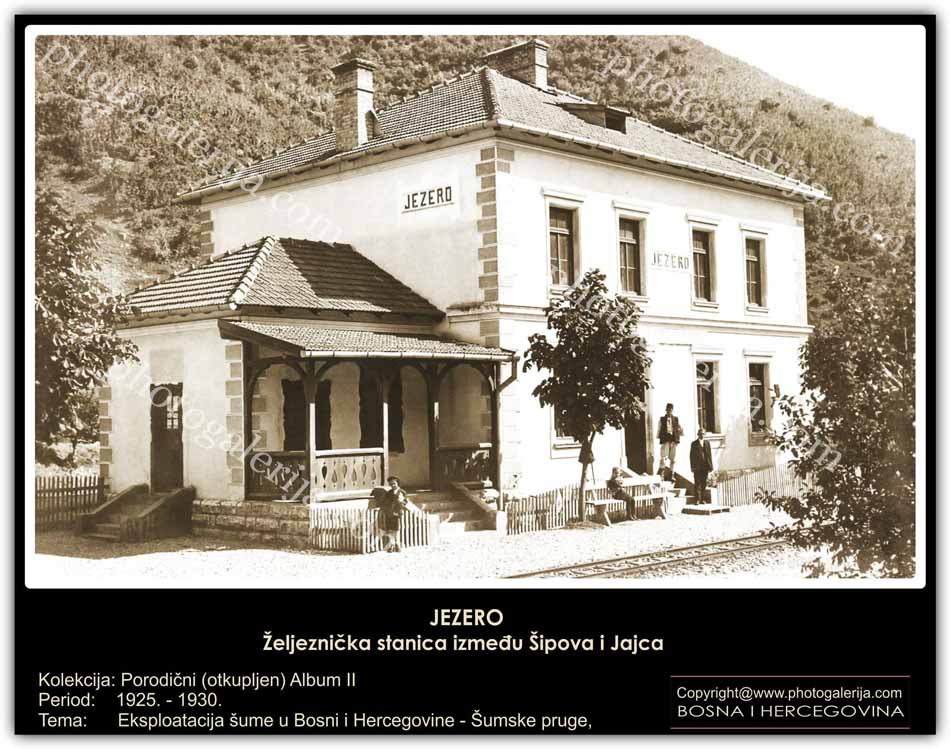

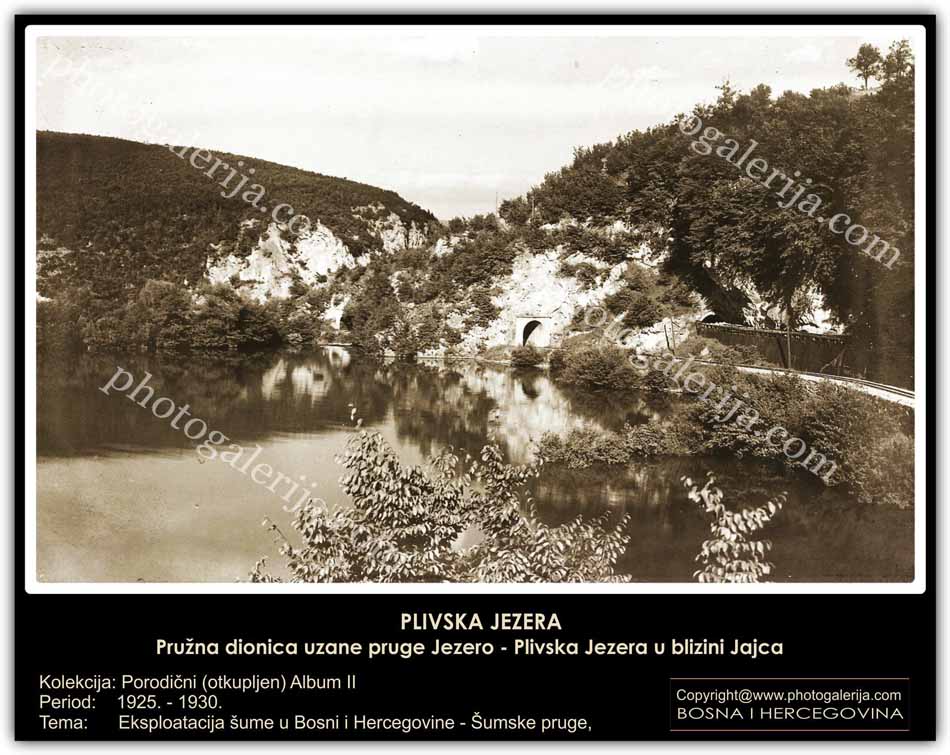

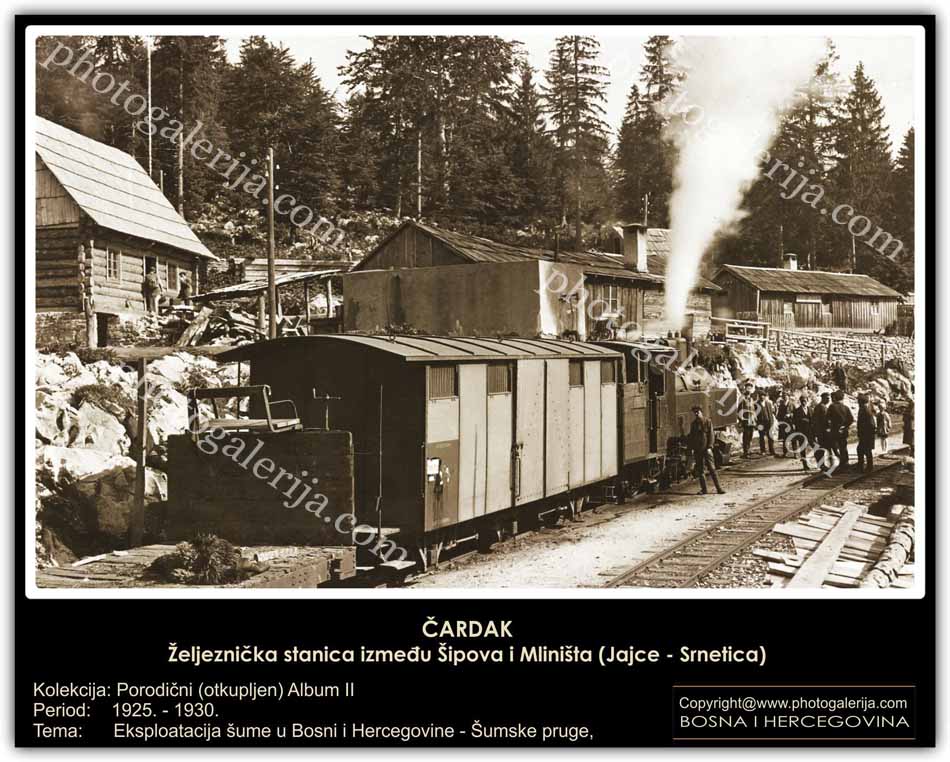

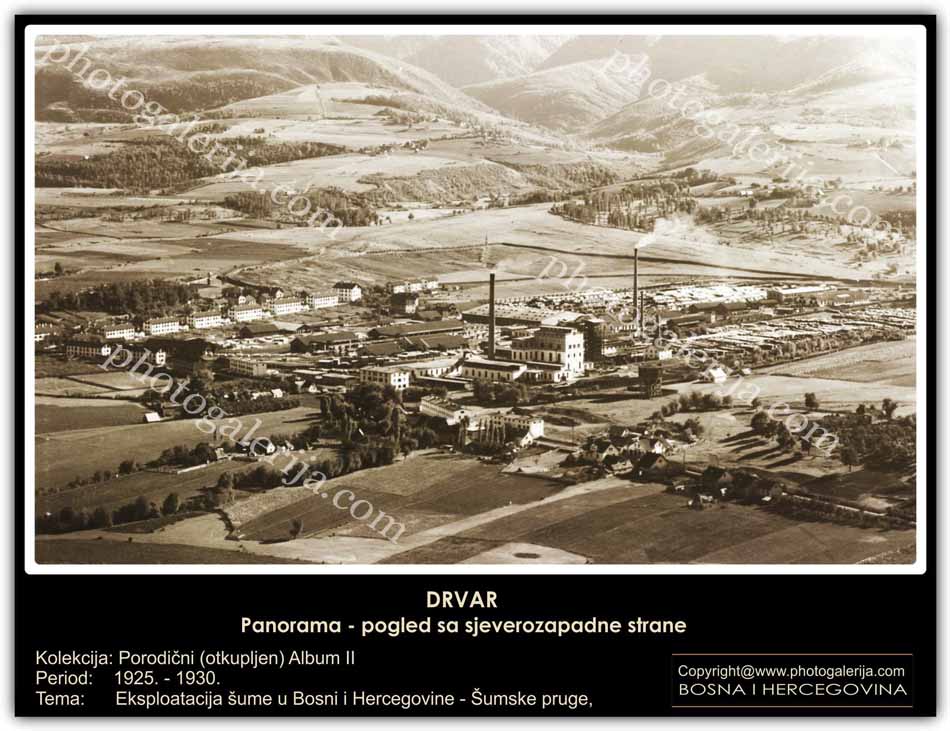

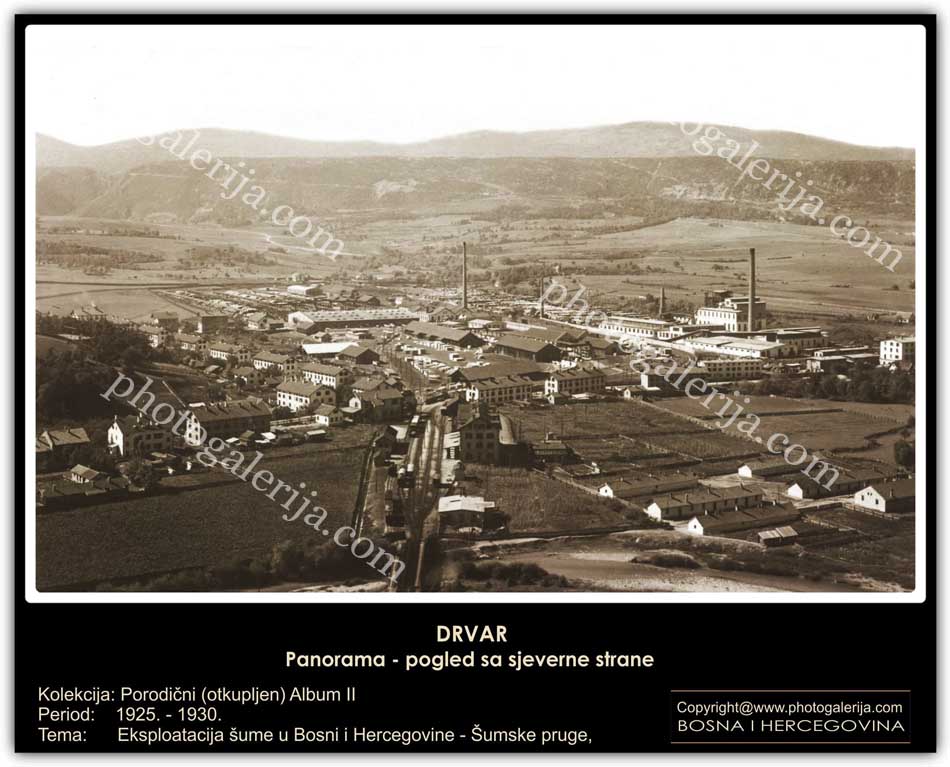

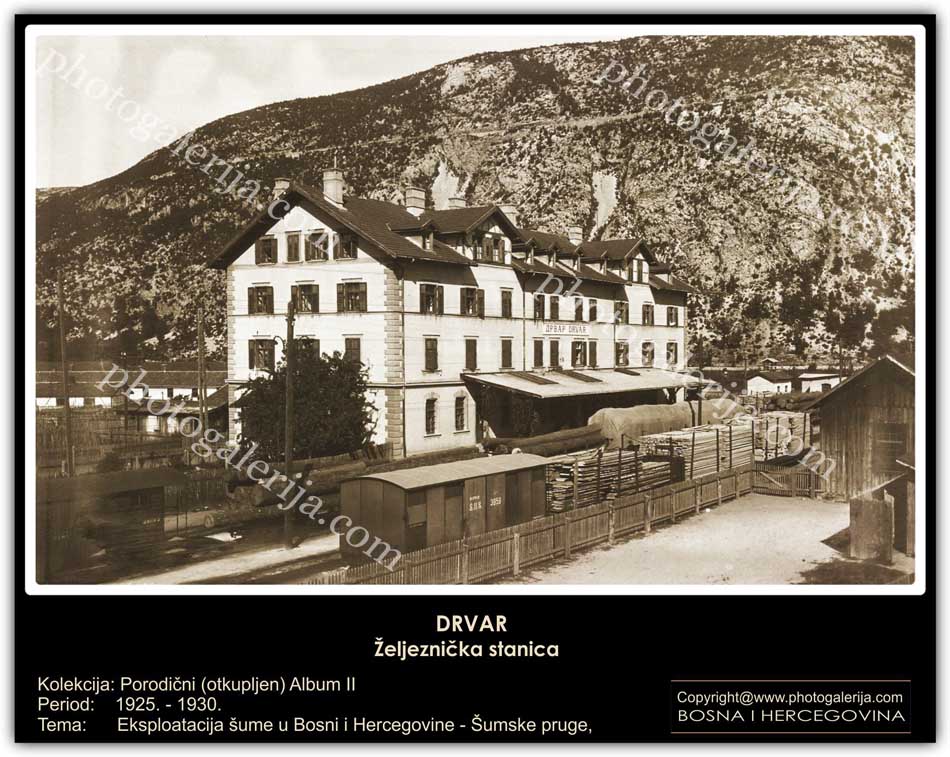

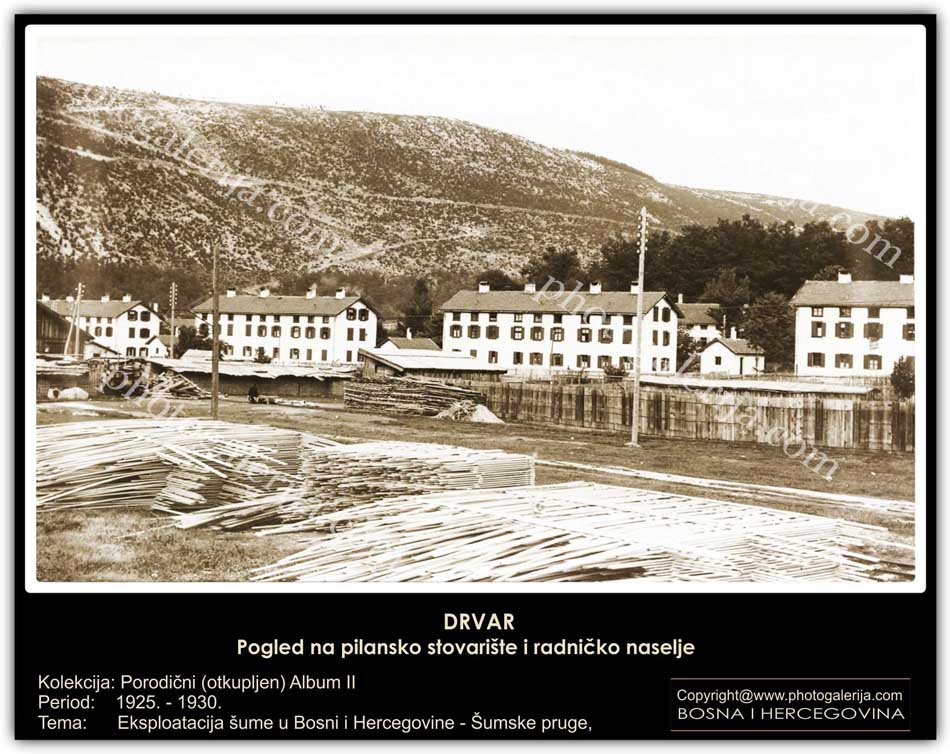

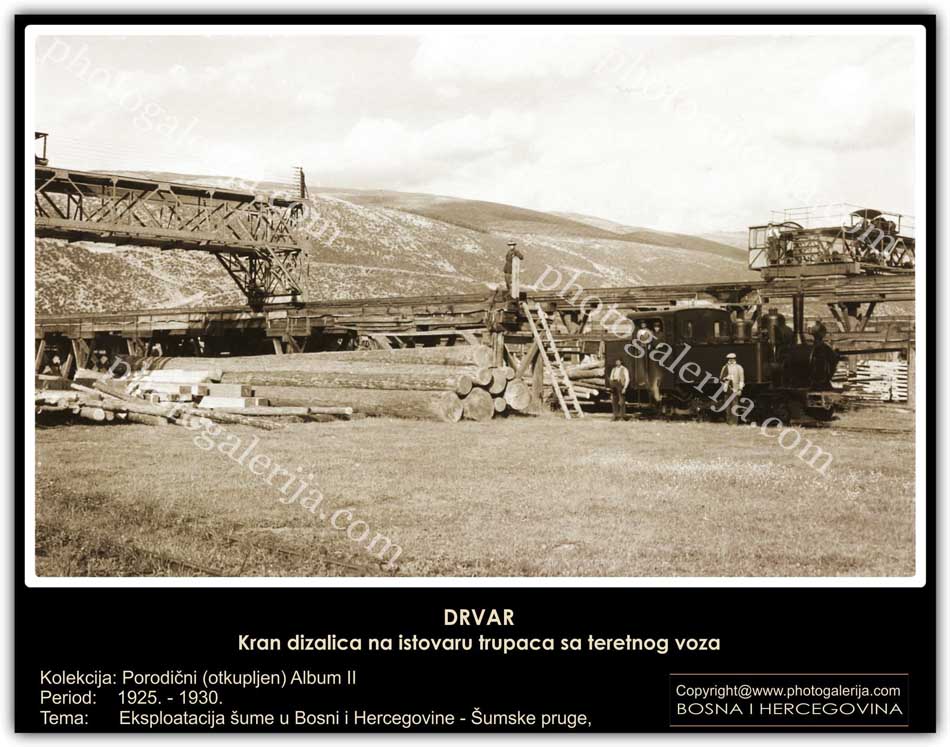

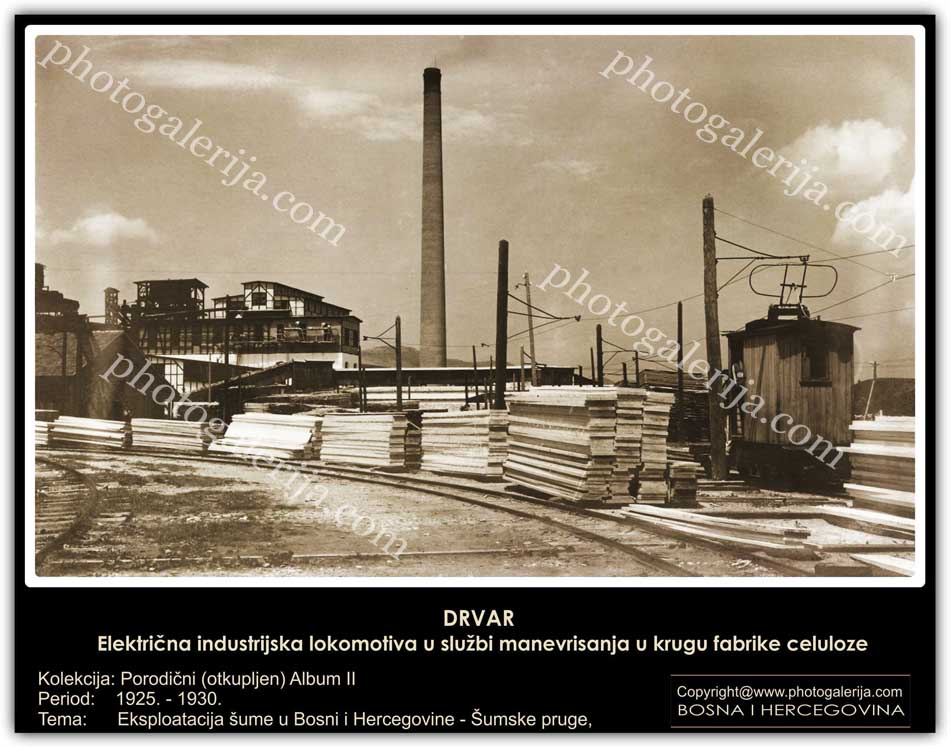

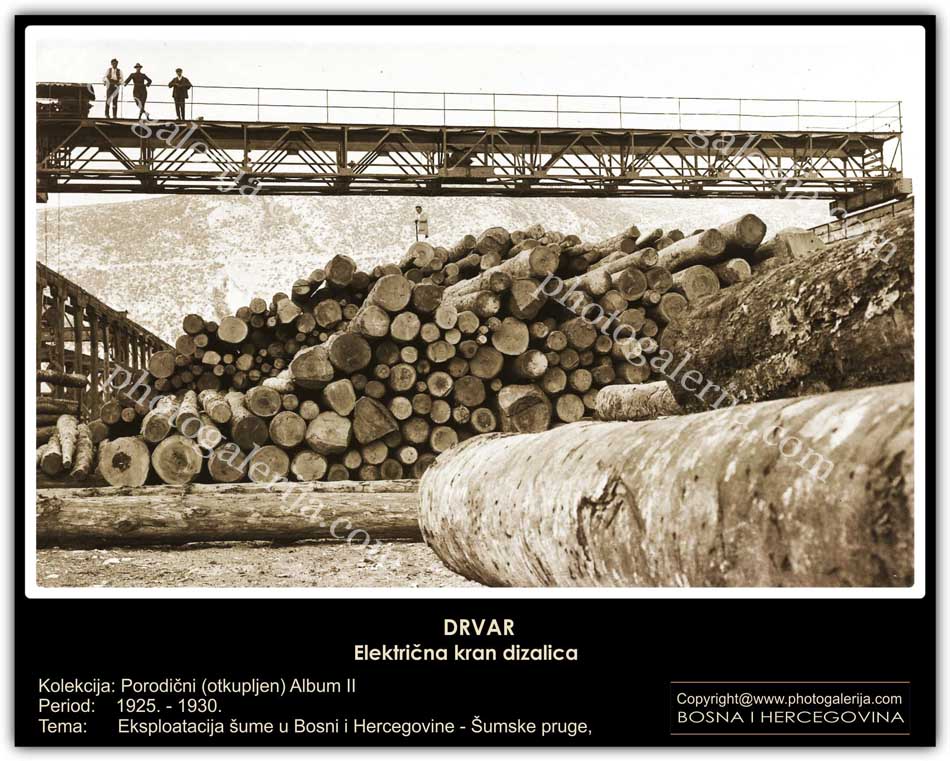

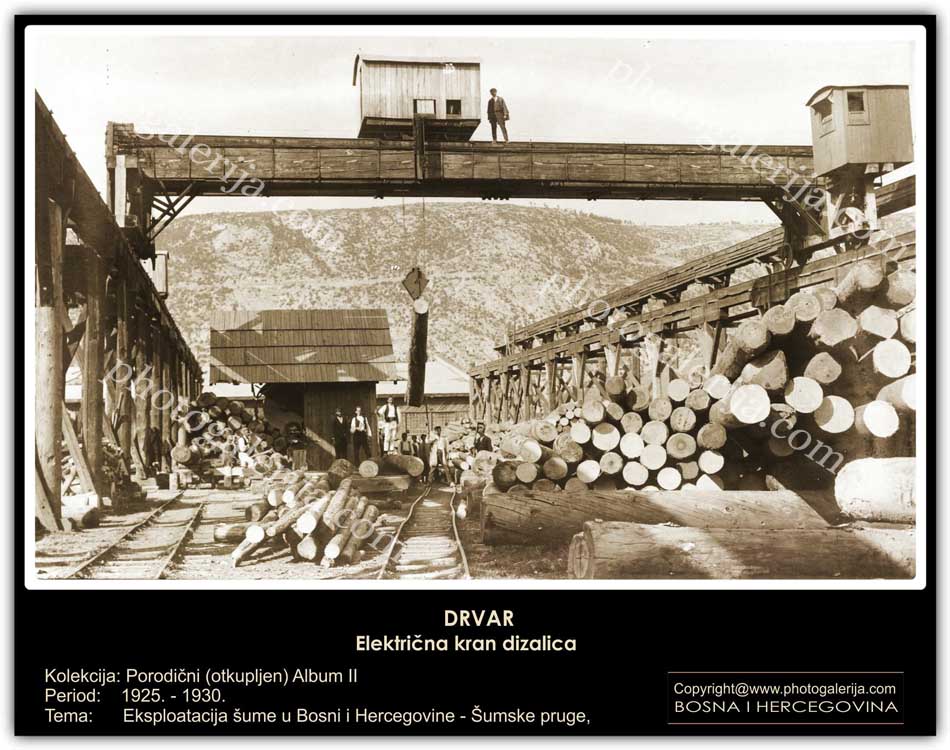

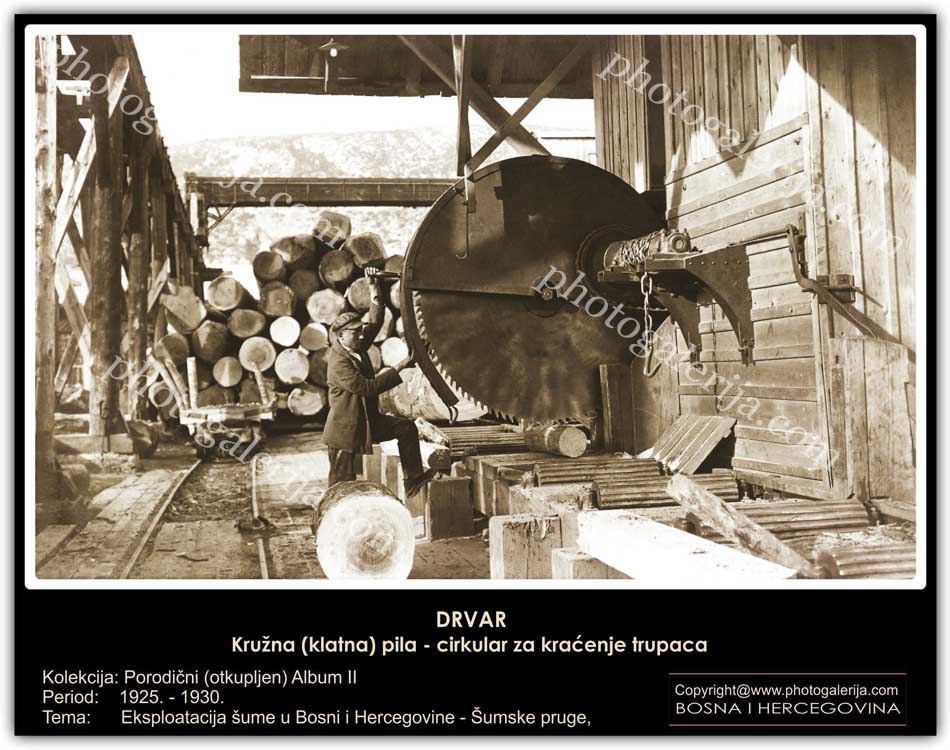

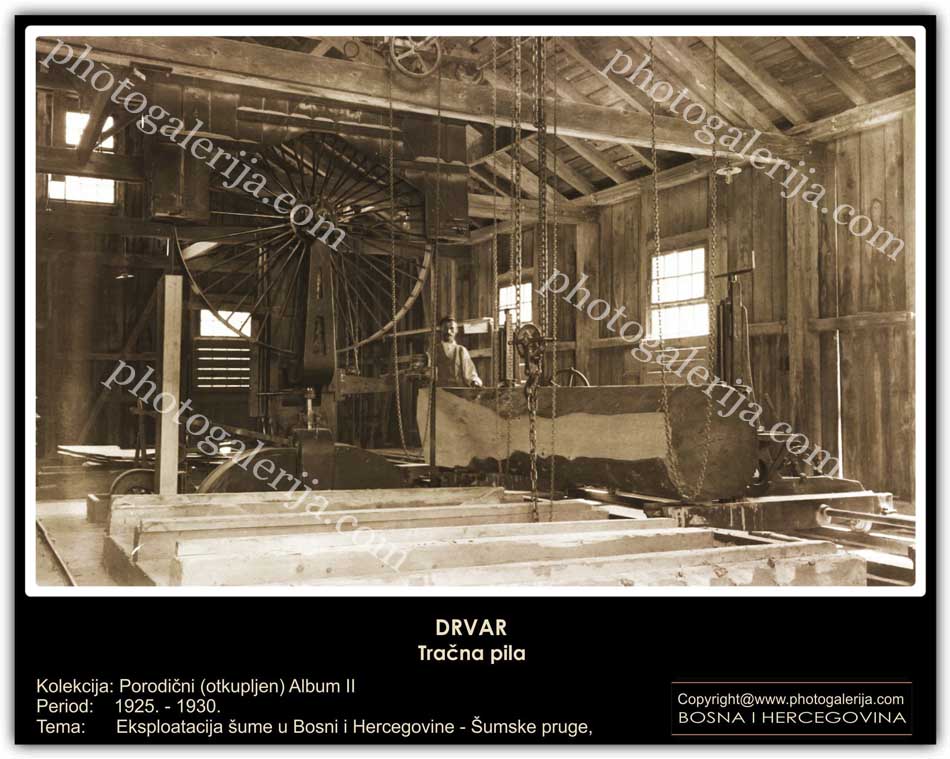

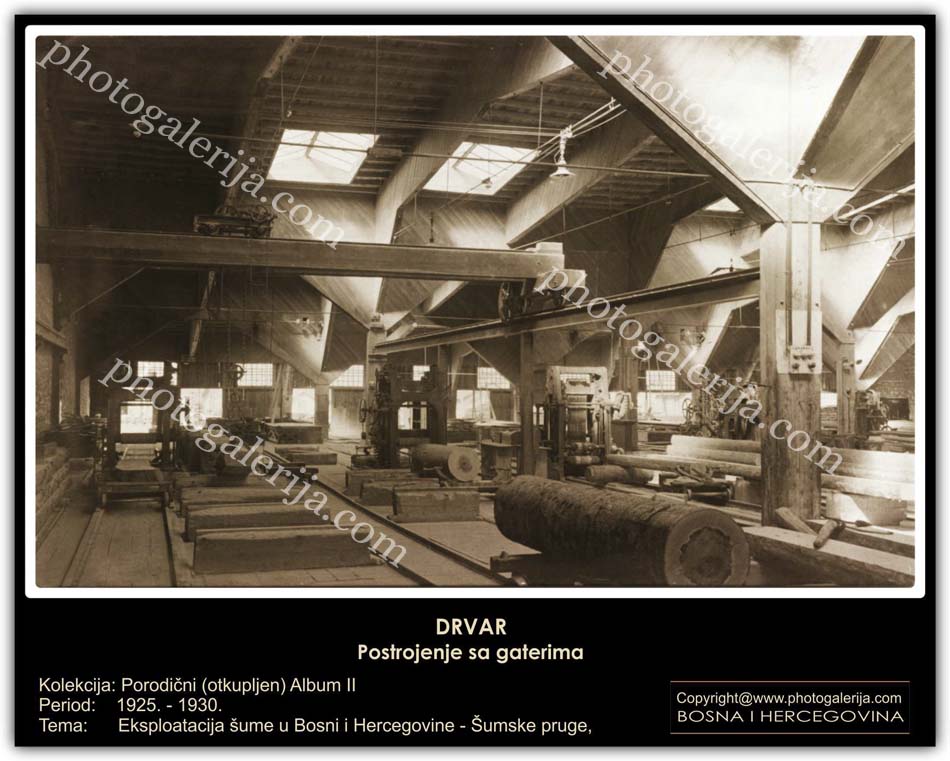

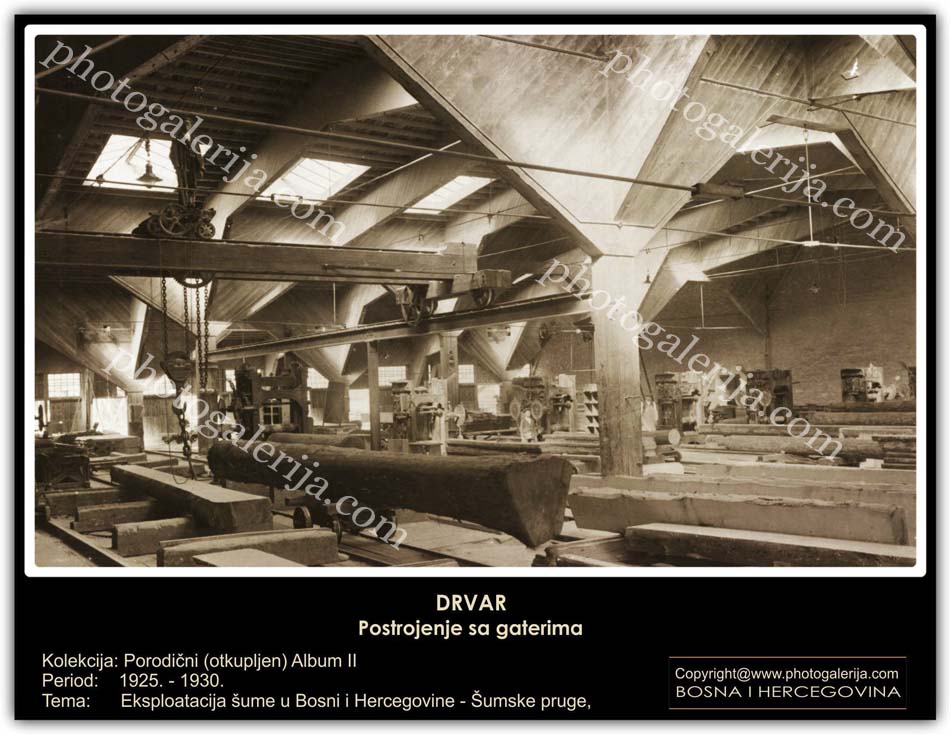

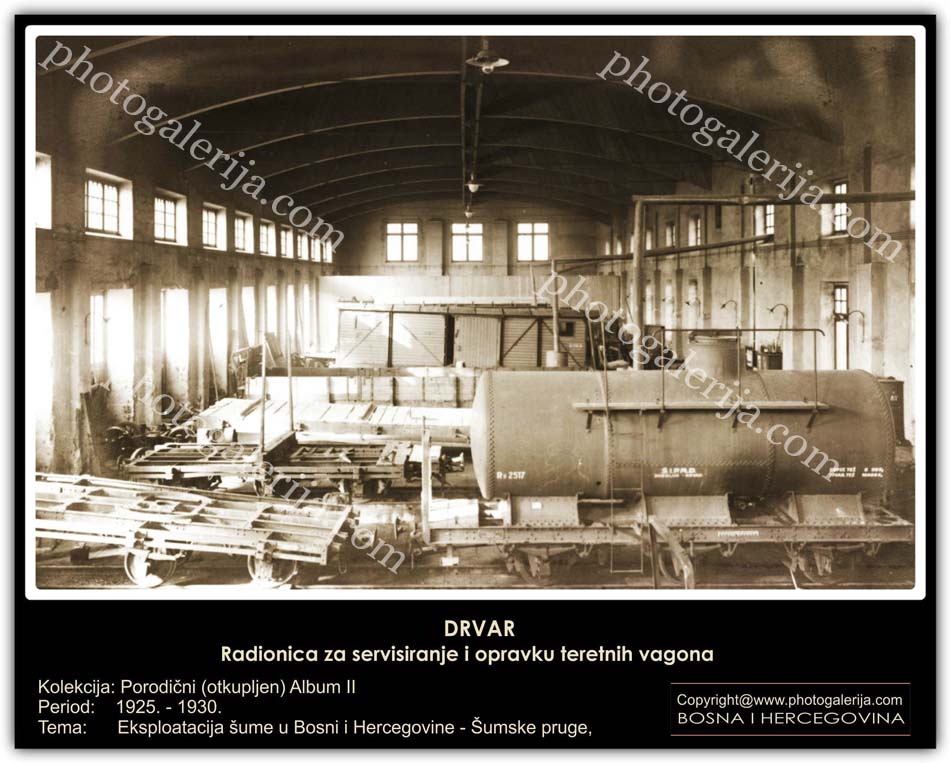

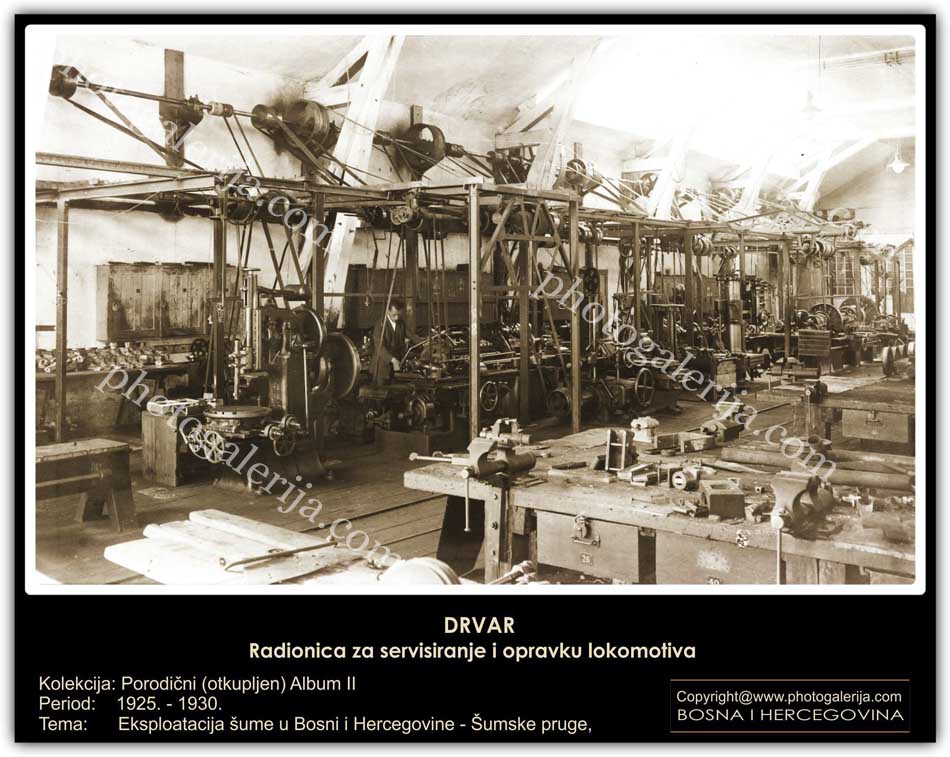

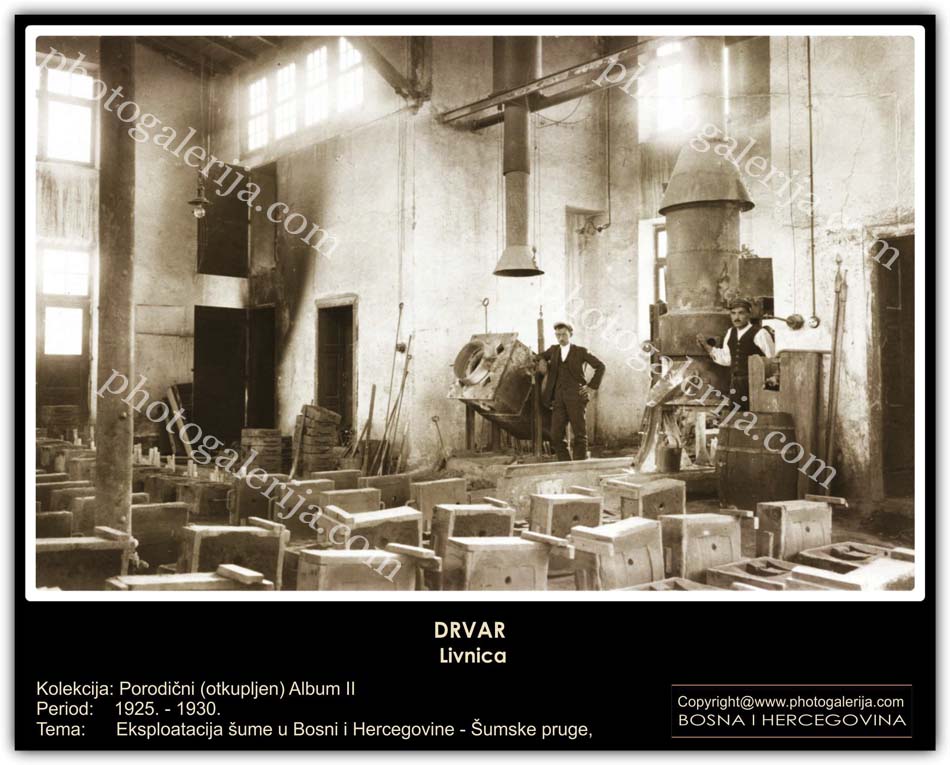

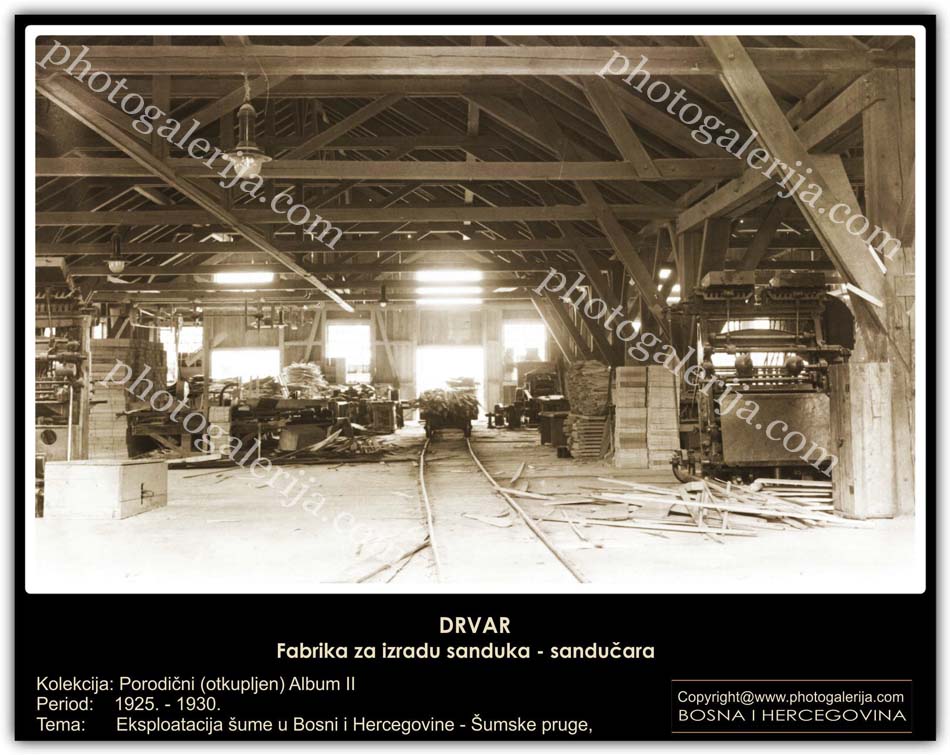

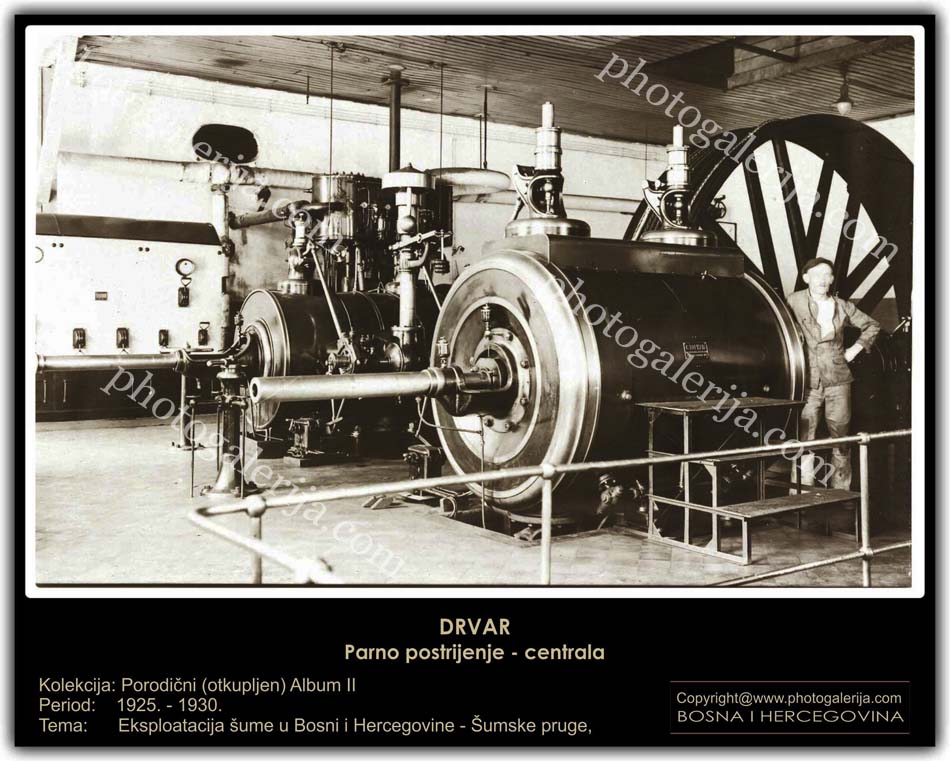

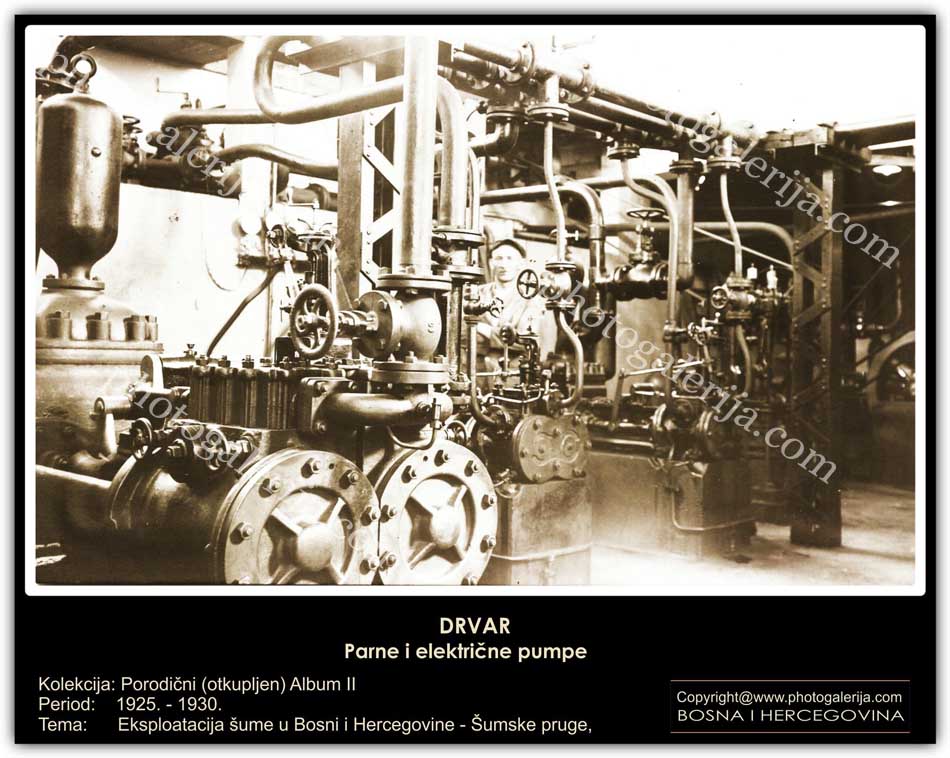

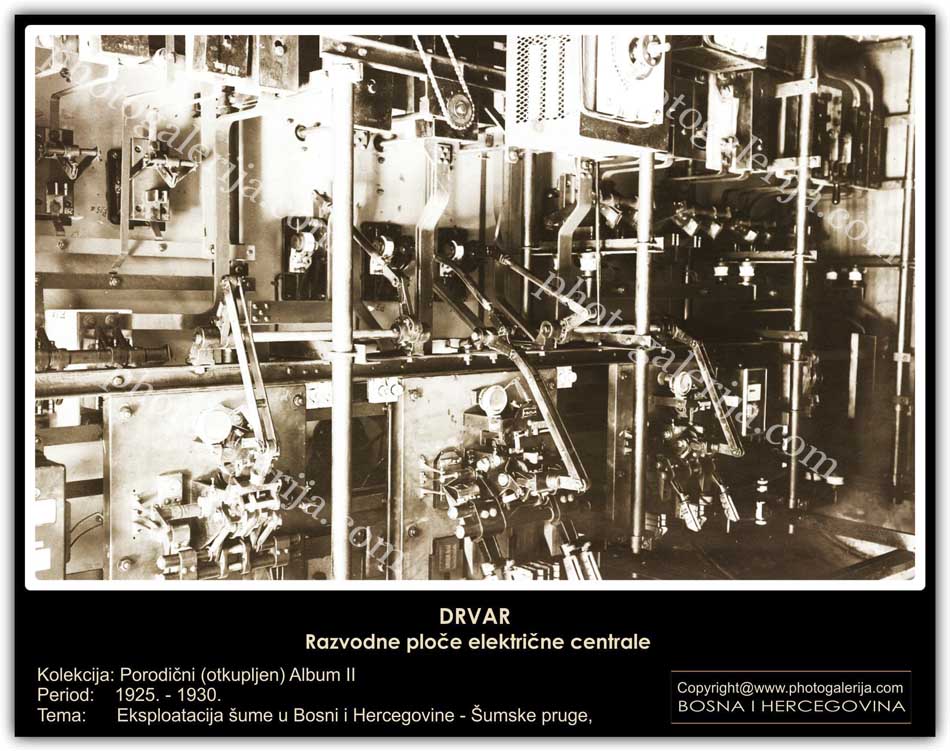

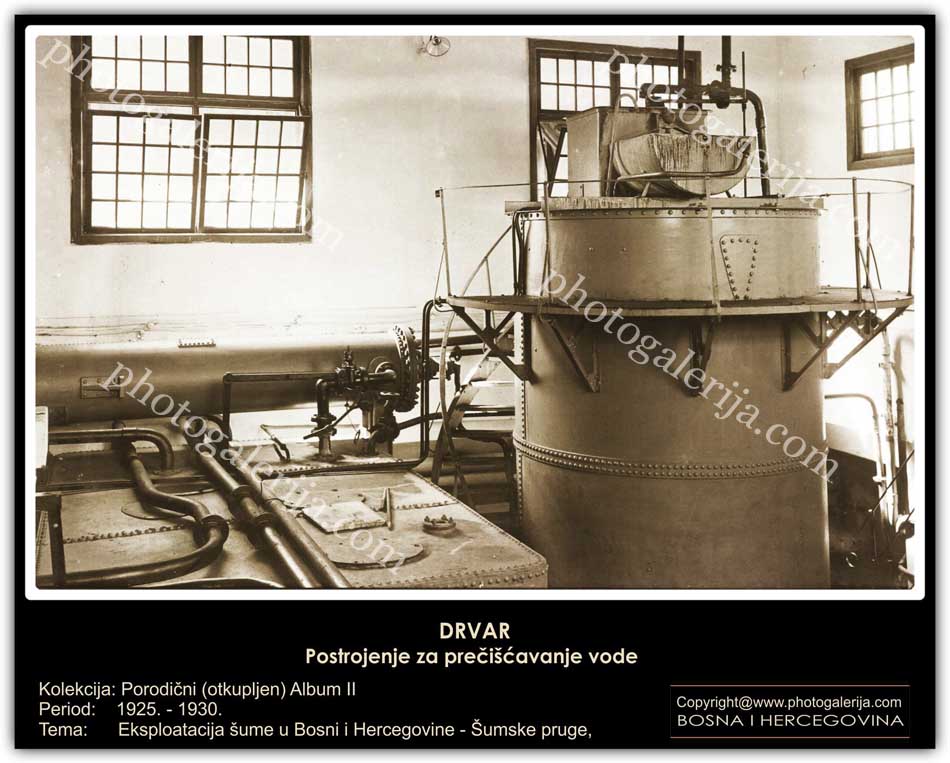

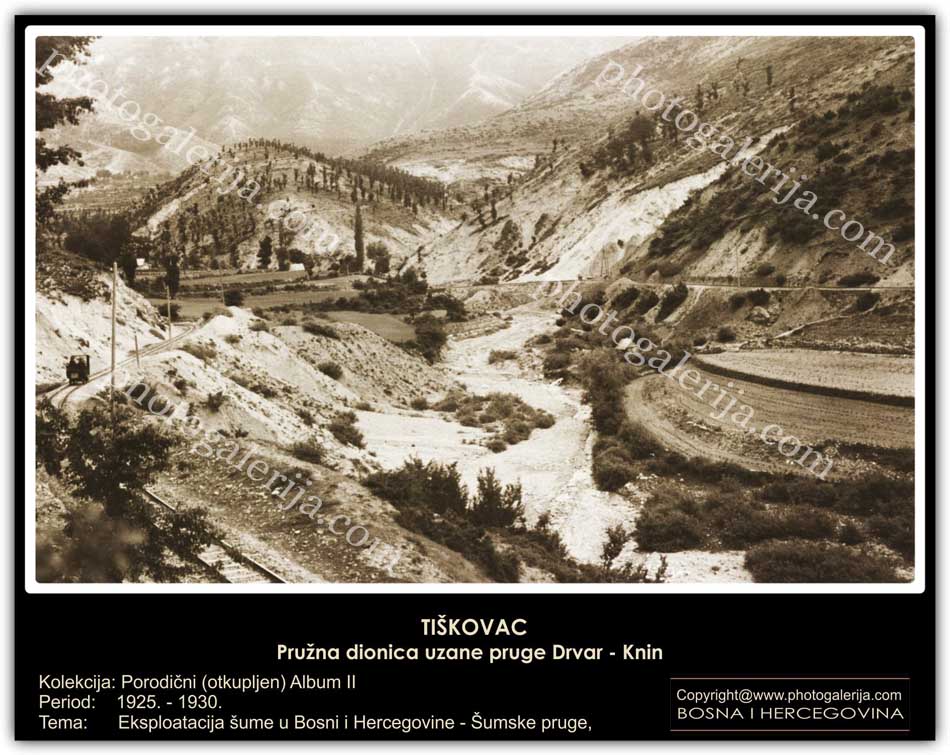

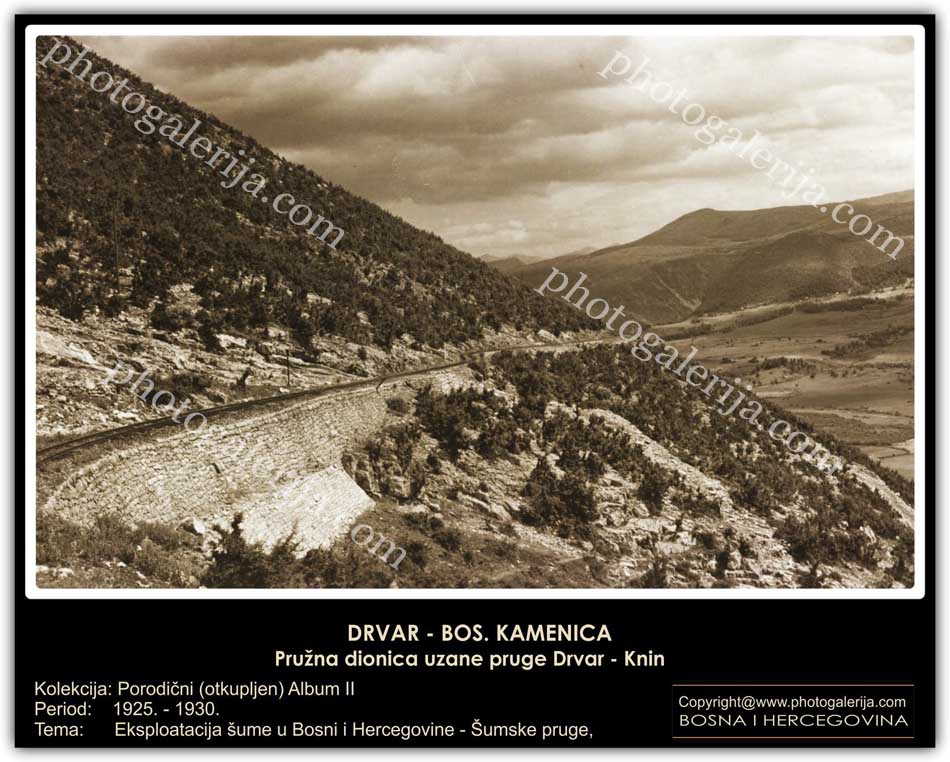

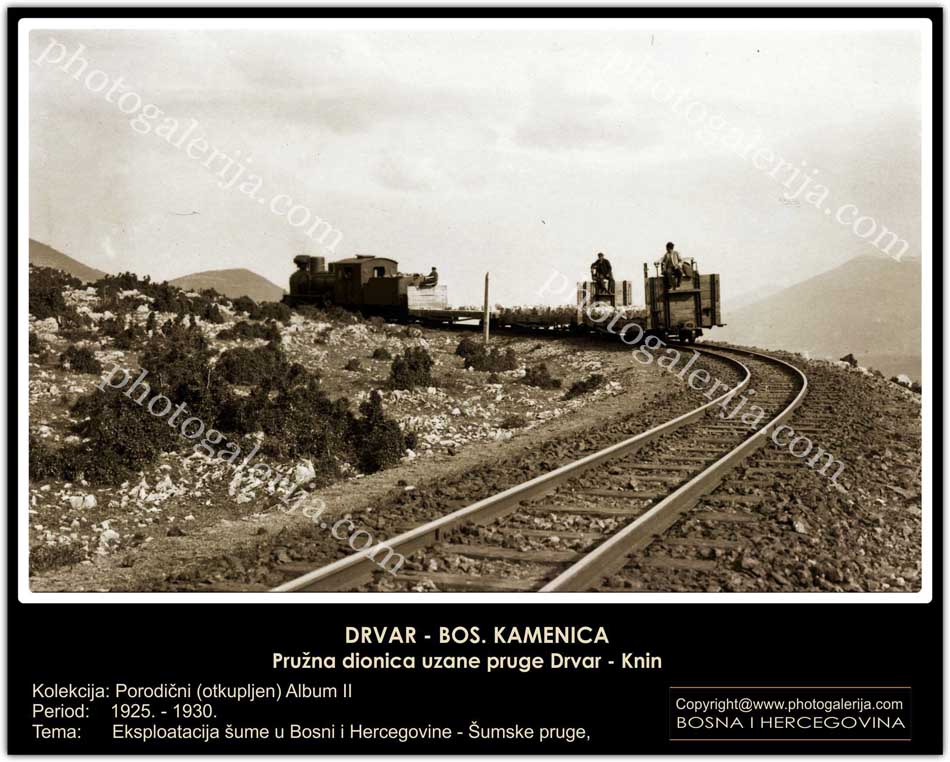

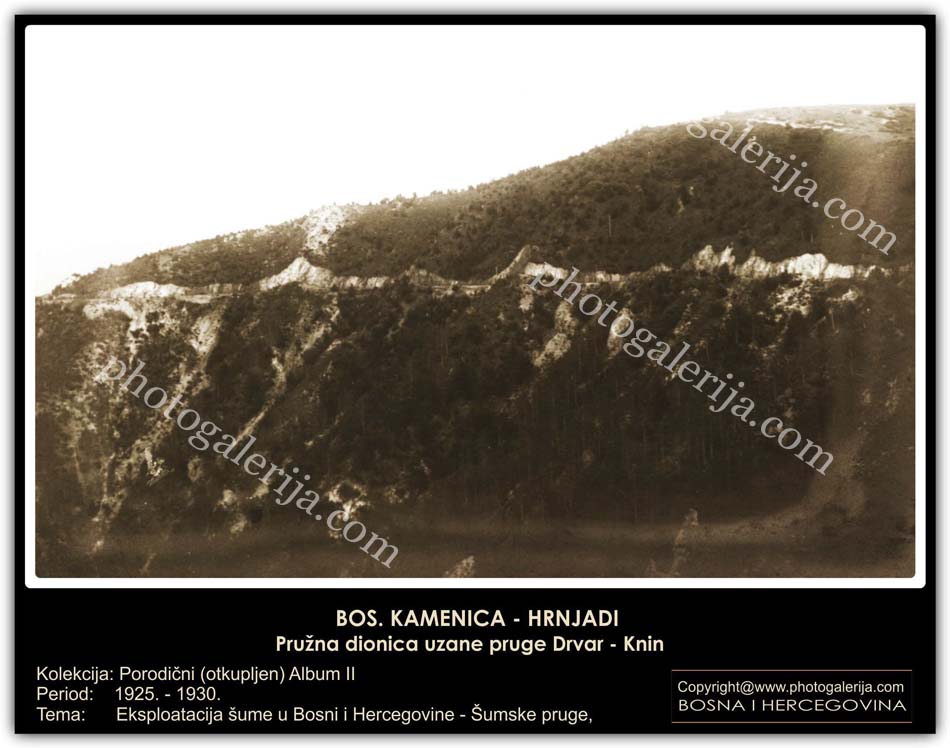

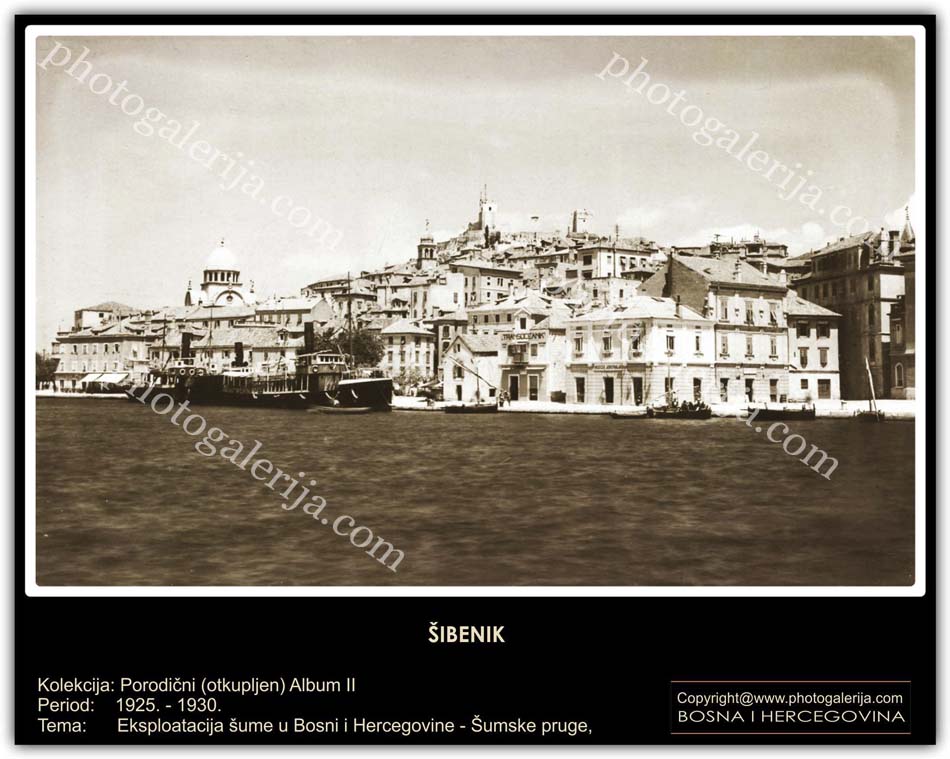

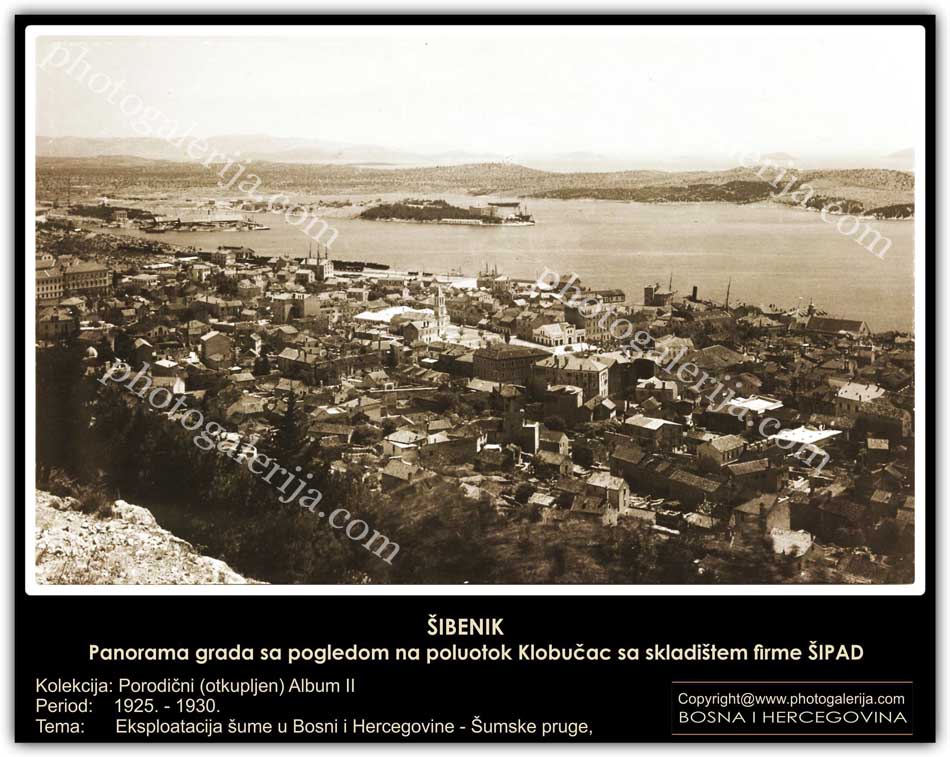

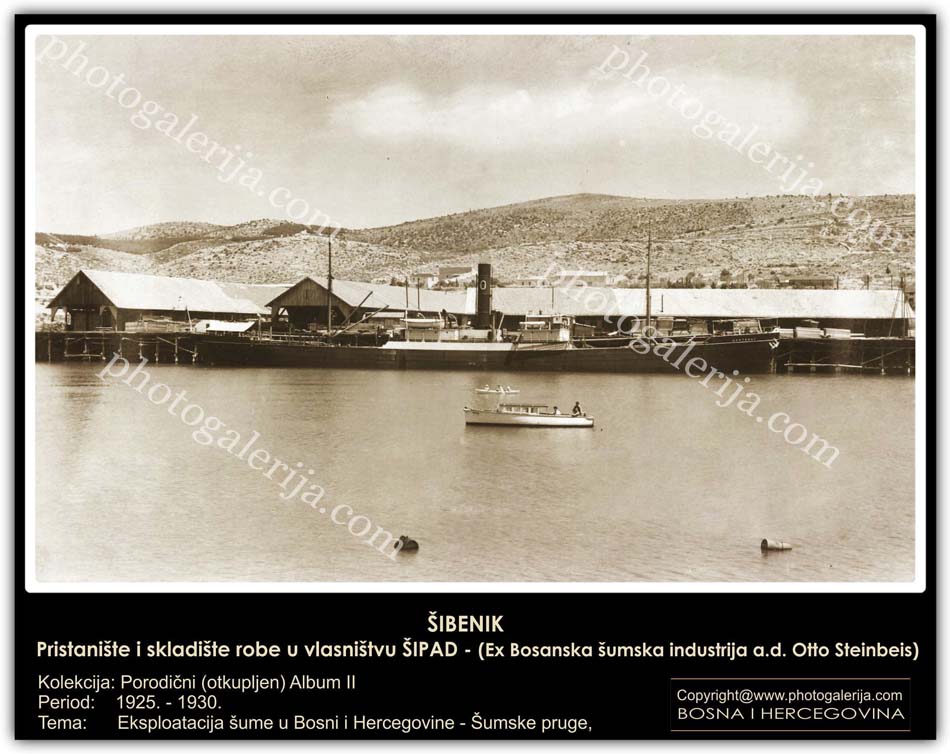

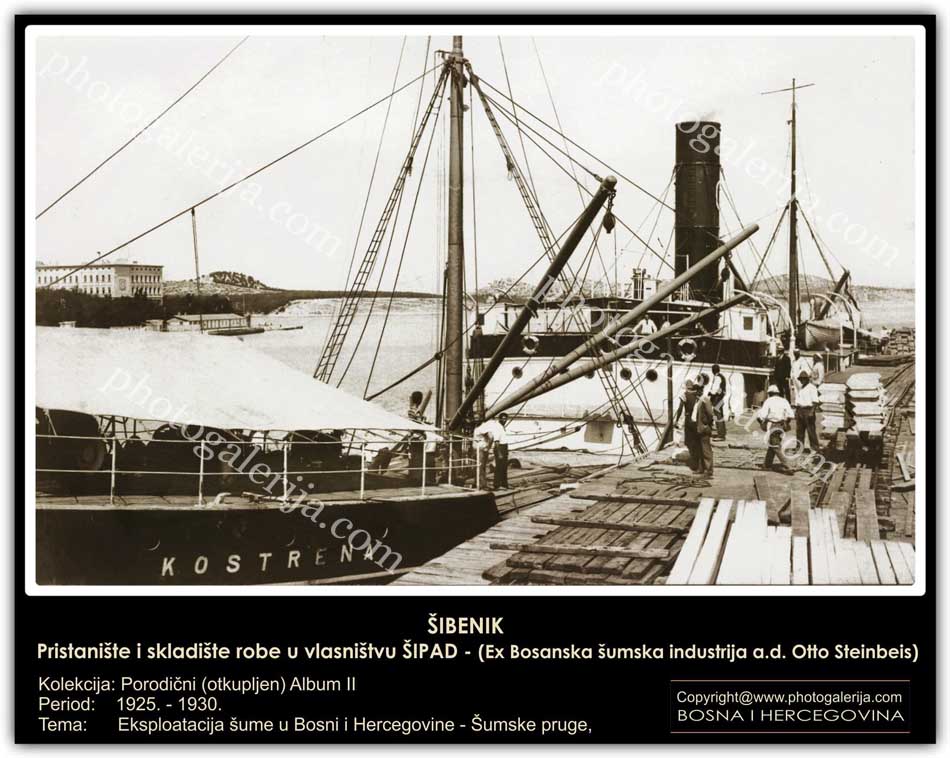

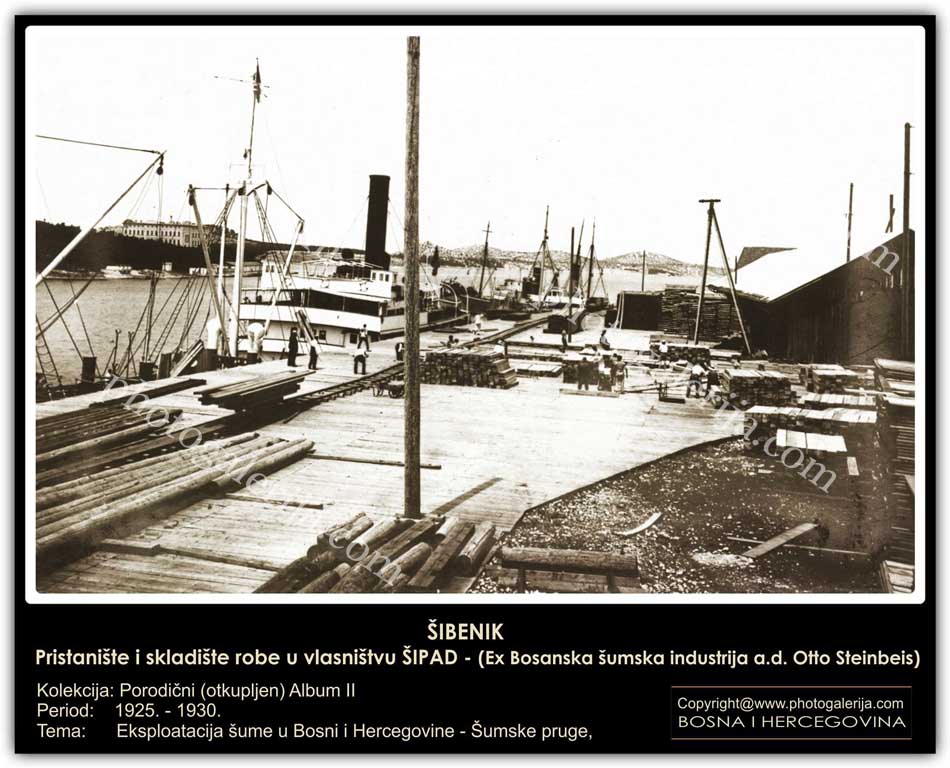

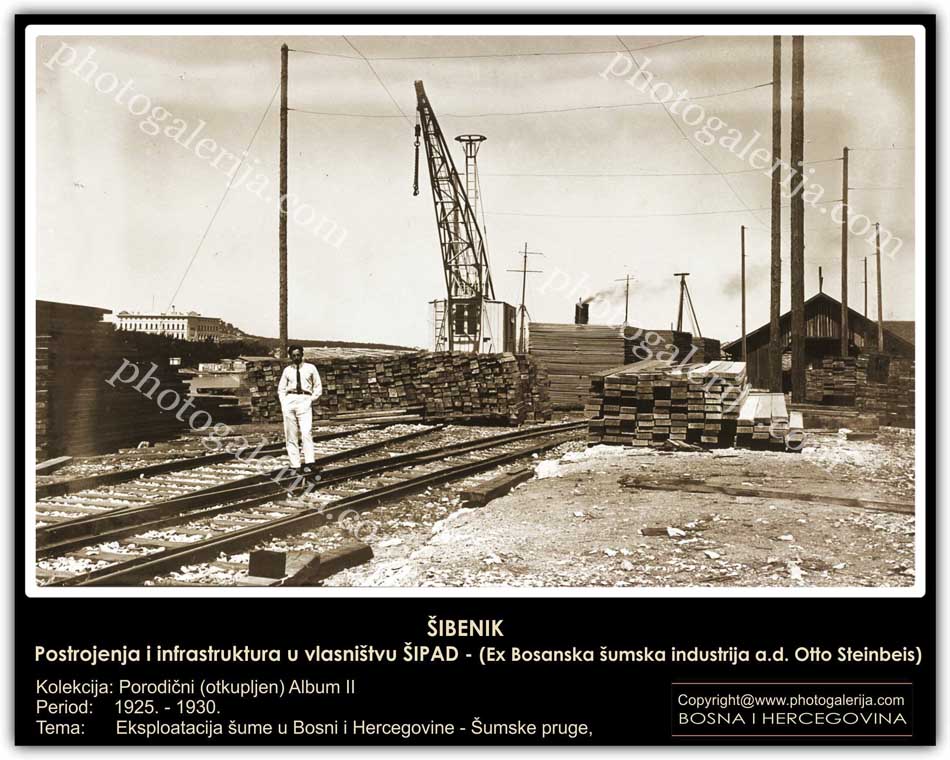

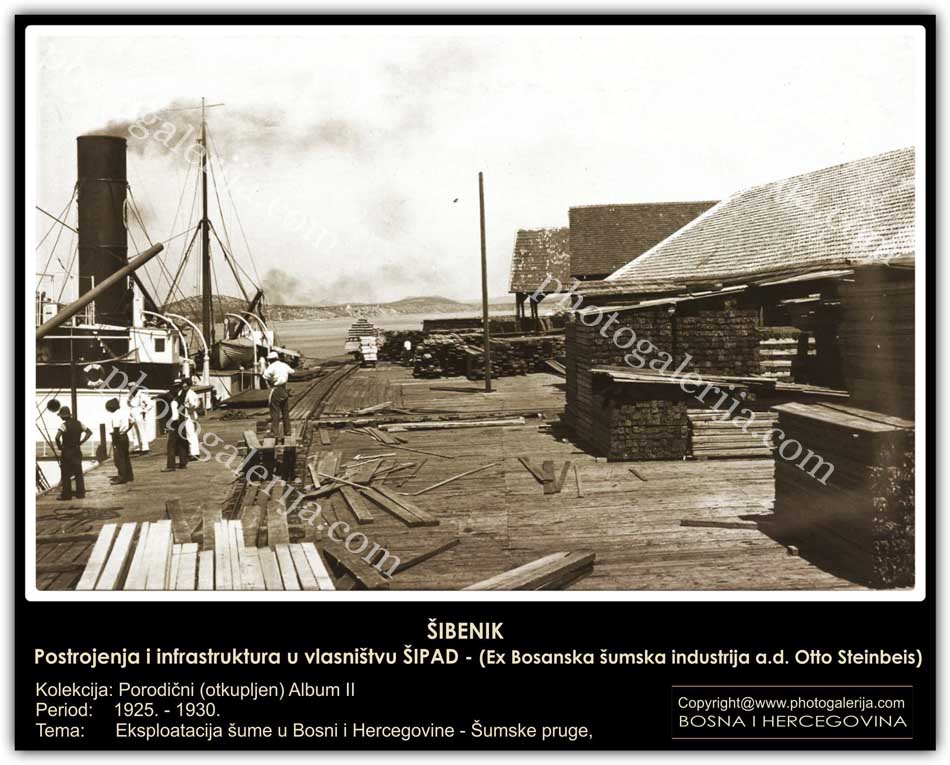

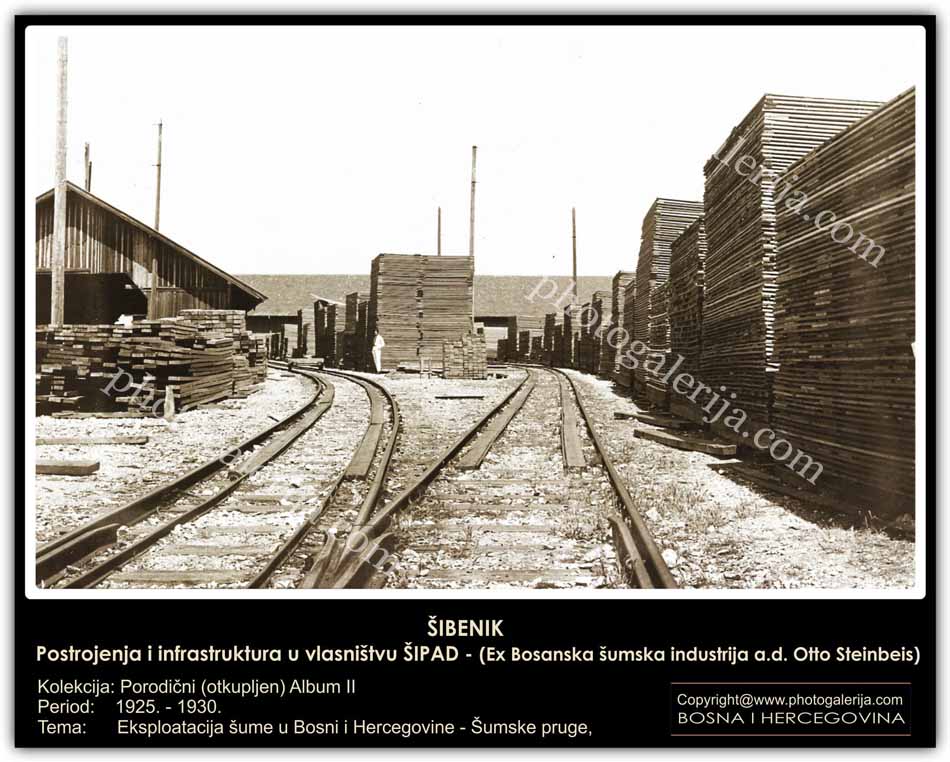

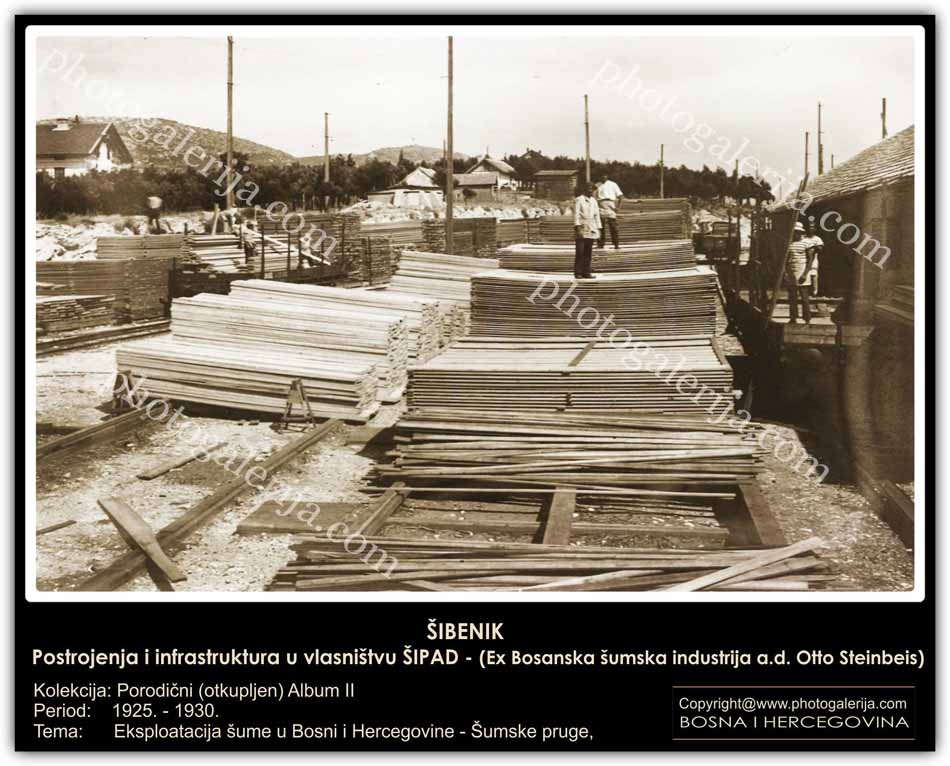

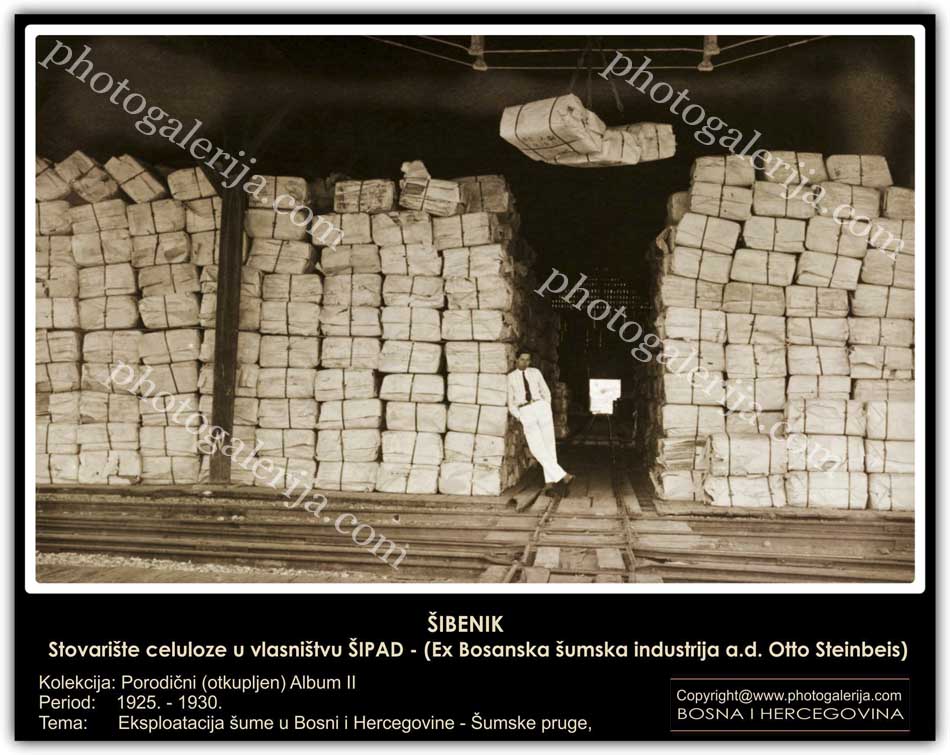

For the purpose of attracting foreign capital and joint ventures in the exploitation of Bosnian forests, the first agreements were made, and we would like to highlight the most significant ones: Bosnian Forest Industry Ltd. Otto Steinbeis in Dobrljin-Drvar, Bosnian Forest Industry Eisler & Ortlieb Zavidovići, G. Gregersen & Sons Forest Industry in Zavidovići, Bosnian Wood Industry Ltd. Gustav Mechtersheimer in Višegrad, J. Brabetz Company in Gospodći, Bosnian Wood Industry Consortium Oskova-Gostilja-Puračić, “Una” Wood Industry Ltd. in Bosanska Dubica, Josef Banheyer and son Vukovar-Srebrenica, Buttazzoni & Venturini Wood Industry Ltd. in Sarajevo, Zadik S. Finci Company Sarajevo-Pale, Rafael Z. Finci Company and Tarčin-Sarajevo cooperative, among others. At the end, during Austro-Hungarian rule (1878/1918) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, covering an area of approximately 51,000 square kilometers, two-thirds of which was forested, capitalists (exploitors in service of the Monarchy) managed to cut about 18.5 million cubic meters of wood, which, according to contracted obligations, accounts for approximately 52% of the total realized volume. The remaining 48% of unexploited forests remain a regret and a memory of times when they measured and wandered through Bosnian wooded mountains, marveling at the height, embarkment, and purity of Bosnian trunks. Immediately after the end of the war (and during the war), owners of these companies lost ownership rights in favor of the Kingdom of SHS, which confiscated and inherited all estate lands, facilities, and constructed forest railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The best example of inheritance is the case of the state enterprise “Šipad,” which, as the new operator, utilizes all the acquired infrastructure in that part of Bosnia and cape Klobučac with a built harbor in Šibenik and about 400 km of railway lines from German industrialist and banker Otto Steinbeis. During this period, the phrase “Steinbeis Railway” (“Steinbeis-Bahn”) remained among the people, later replaced by “Šipad railway lines.” It is difficult to ignore the history of the founding of this large company (“Bosnische Forstindustrie AG Otto Steinbeis”), as we believe it is less known to generations born after the seventies of the last century when the narrow (and all forest) railways in that part of Bosnia and Herzegovina were definitively abolished. Otto Steinbeis founded and registered the company under his name in 1892, and in 1900, transformed his enterprise into a joint-stock company called “Bosnian Forest Industry Ltd. Otto Steinbeis Dobrljin-Drvar.” He divided the exploitation areas into two gravitational zones: forests of the northern part that drain into Nera and Una, and the southern area in the Una valley. Accordingly, one sawmill was situated on the Una River in Dobrljin, and another in the Una valley in Drvar. The transportation of logs to Dobrljin was primarily water-based, while in Drvar, rail was used. It is also worth mentioning the exploitation area in the Vrbas valley, where wood was transported by rail from Jajce to Turbeta, via Srnetica to Drvar. During the exploitation of forests (the first contract was signed in 1892 with the Royal Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina for twenty years of exploitation, and in 1900 with the newly established company for thirty years), from its founding until the outbreak of World War I, the main railway lines were constructed, facilitating the transport of timber from the forests within approximately 346 km of locomotive-operated tracks, along with an additional 80 km of gravitational tracks. Srnetica was designated as a central hub, connected to the state railway network by three branches: one via Sanski Most to Prijedor on the main standard gauge line to Dobrljin; another via Oštrelj, Drvar, and Tiškovac to Knin and Šibenik; and a third via Mliniste from Jajce. The rolling stock consisted of 24 steam locomotives with about 1,300 wagons for transporting wood and other materials, as well as an electric railway within the pulp mill operation in Drvar, powered by electricity from a small built-in thermal power plant. These lines formed a continuous network until their decommissioning in 1976. Additionally, there were 11 built electrified switchbacks (wire railways – funiculars) totaling 6,400 meters, 11.5 km of forest roads, and roughly 155 km of river courses used for rafting (Una, Sana, Unac, Ribnik, Vrbas, etc.)

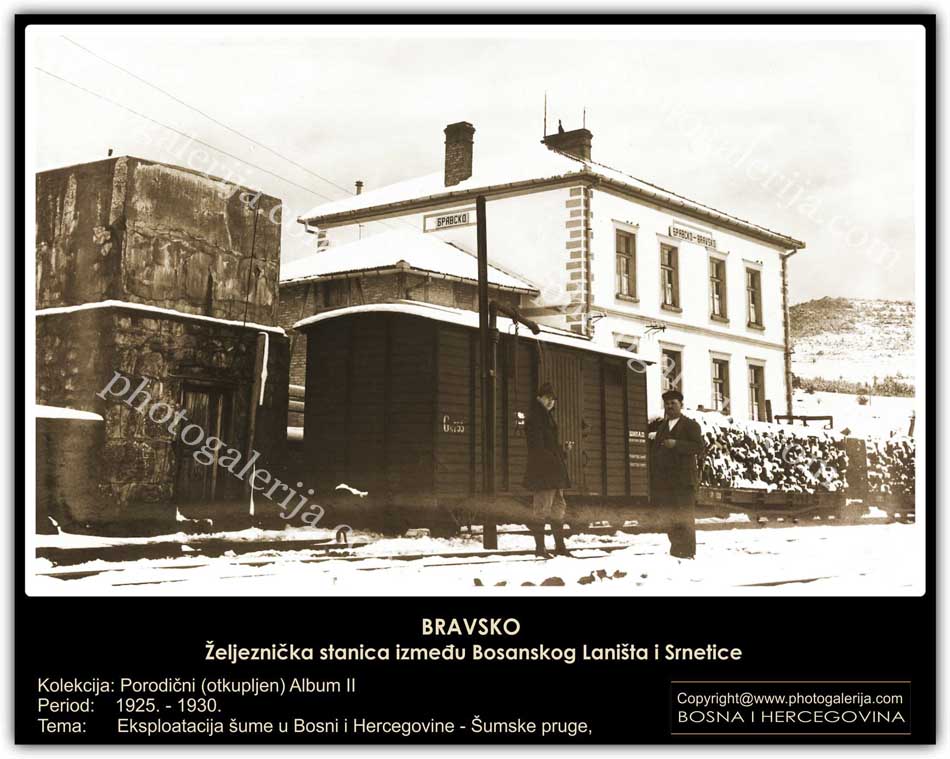

It is difficult to ignore the history of the founding of this large company (“Bosnische Forstindustrie AG Otto Steinbeis”), as we believe it is less known to the generations born after the seventies of the last century, when the narrow (and all forest) railways in that part of Bosnia and Herzegovina were definitively abolished. Otto Steinbeis established and registered the company in his name in 1892, and in 1900 converted his enterprise into a joint-stock company called “Bosnian Forest Industry A.D. Otto Steinbeis Dobrljin-Drvar.” He divided the exploitation areas into two gravitational zones. The forests in the northern part, which border the Neretva and Una rivers, and those in the southern part, in the Una valley. Accordingly, one sawmill was located on the Una River in Dobrljin, and another in the Una valley in Drvar. Transit of logs to Dobrljin was mainly done by water, while in Drvar, the railway was used. Additionally, it is worth mentioning the exploitation area in the Vrbas valley, where the wood was transported by railway from Jajce to Turbeta, or across Srnetica to Drvar.

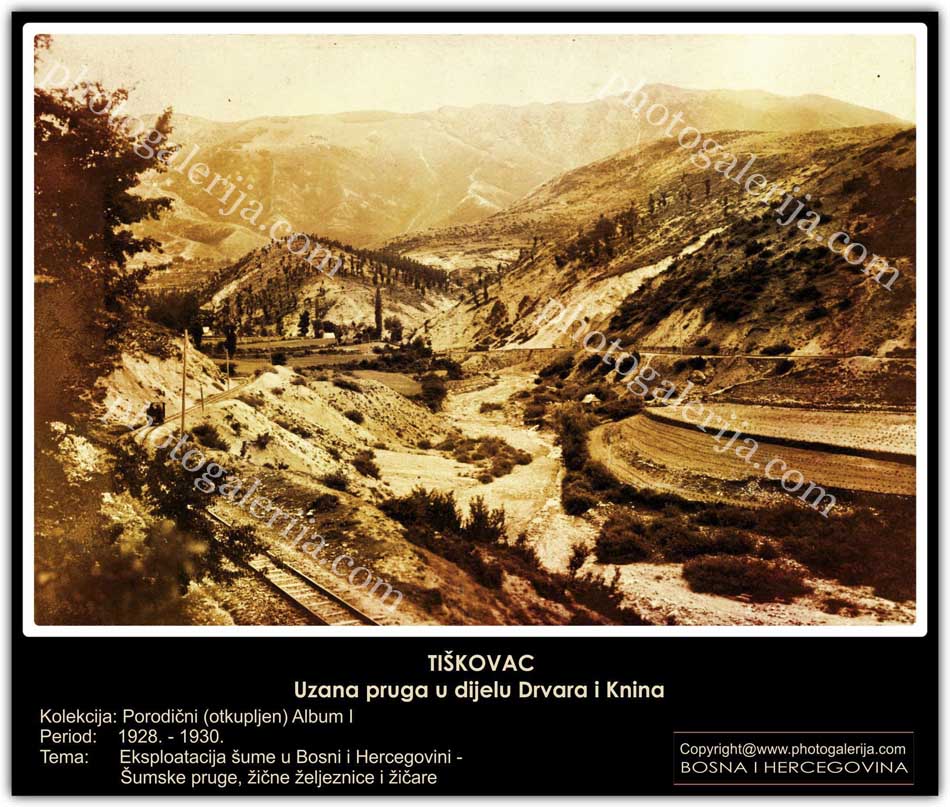

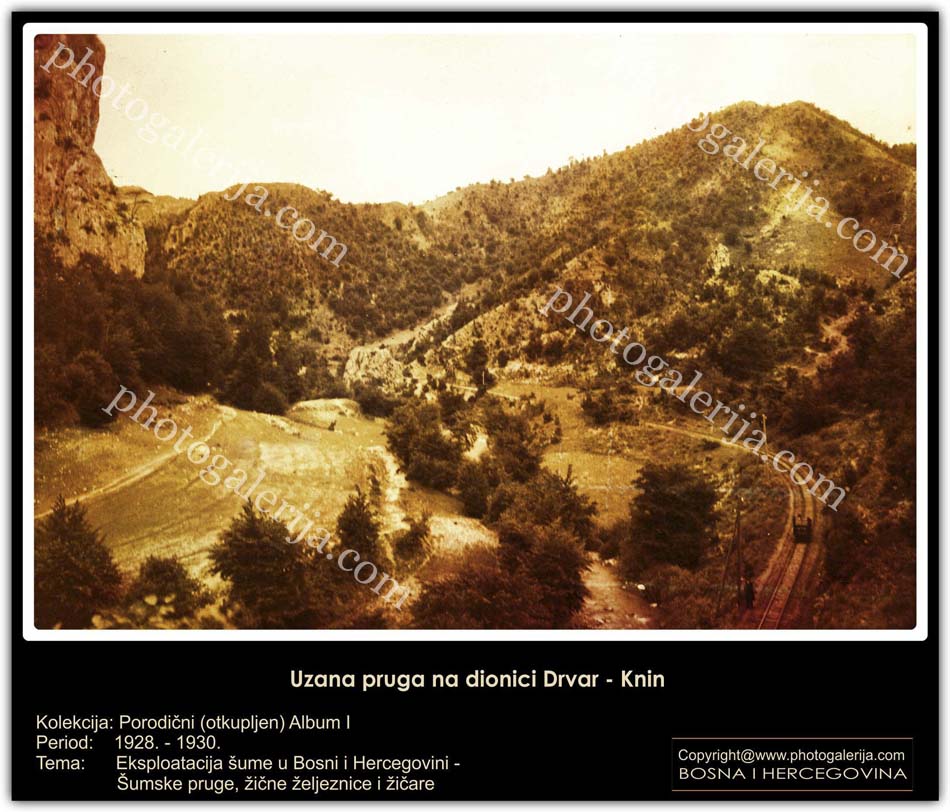

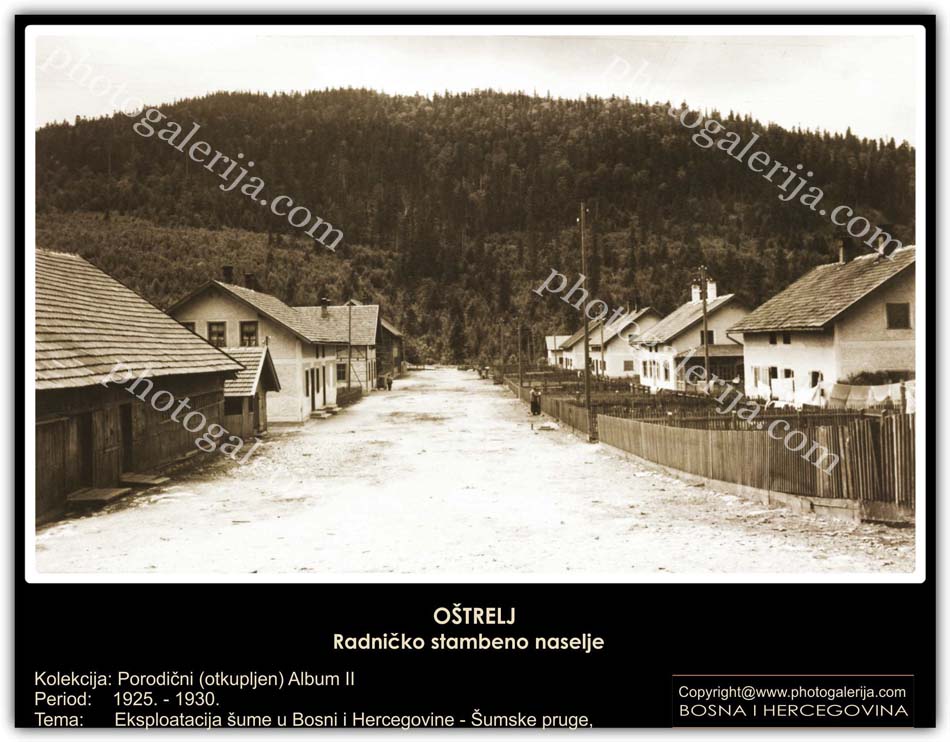

During the exploitation of the forest (the first contract was signed in 1892 with the State Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina for twenty years of exploitation, and in 1900 with the newly established company for thirty years), from its founding until the outbreak of World War I, it built the main railway lines used to transport timber from the forests of that area over approximately 346 km of steam locomotive-operated railways, as well as an additional 80 km of gravity-powered lines. The central hub and junction was designated as Srnetica, which connects to the state railway network via a branch line through Sanski Most to Prijedor on the main standard-gauge railway, another branch through Oštrelj, Drvar, and Tiškovac to Knin and Šibenik, and a third branch via Mliniste to Jajce. The fleet comprised 24 steam locomotives with approximately 1,300 wagons for transporting wood and other materials, along with an electric railway within the pulp mill complex in Drvar, powered by electricity generated from a small thermal power plant. These lines had the character of continuous routes and remained so until the most recent times, until their discontinuation in 1976. Furthermore, within the contractual area, there were 11 constructed cable railways (wire-powered ropeways) totaling 6,400 meters, 11.5 km of forest roads, and roughly 155 km of river channels used for rafting (Una, Sana, Unac, Ribnik, Vrbas, etc.) to access handling sites and sawmills.

Due to radical personal changes within the jurisdiction of the Joint Ministry of Finance in Vienna and the leadership of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian administration in 1912, as well as based on the harsh campaign by the Bosnian Parliament against him and his enterprise, Steinbeis agreed to the transaction and sold all 60% of the company’s shares in favor of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian treasury. As a countermeasure, the Provincial Government of Bosnia and Herzegovina committed through a special contract to appoint Otto Steinbeis as the general director and as a member of the management board of the new treasury company. After the end of World War I, the company was under the jurisdiction of the relevant ministry in the Kingdom of SHS, until 1919, when the rights over the management (inherited) of the property were granted to a company named Forest Industry Company Dobrljin–Drvar a.d. Sarajevo, and only in 1939 under a new name, Forest Industry Company “Šipad” a.d. After World War II, all property was transferred into the ownership of the New (socialist) Yugoslavia (confiscated as people’s property – social ownership), and the constructed railways of public importance were incorporated into the system of Yugoslav State Railways (JŽ), until their abolition from 1968 to 1975/76. Ultimately, as a curiosity, during and after the wartime events in the newly established Republic of Croatia, a legal dispute continues to this day concerning the registration of rights (new-old) over the space, warehouses, business and other buildings on the Klobučac Peninsula in Šibenik by the heir of Šipad from Sarajevo.

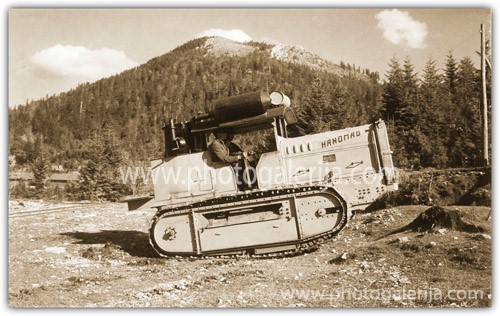

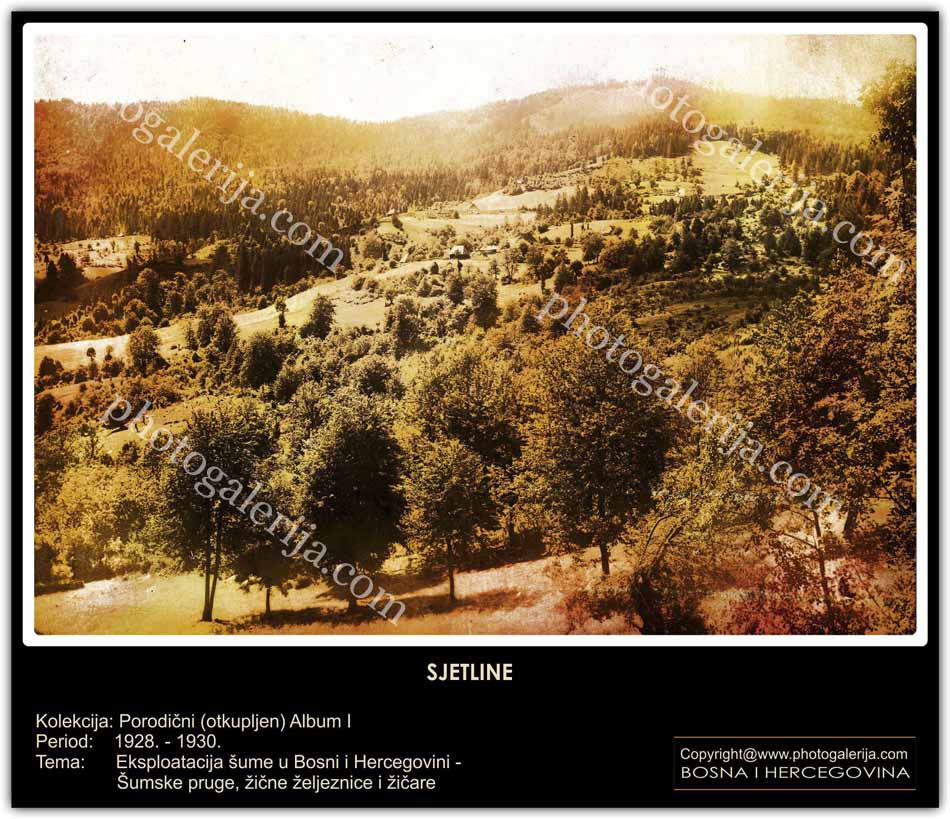

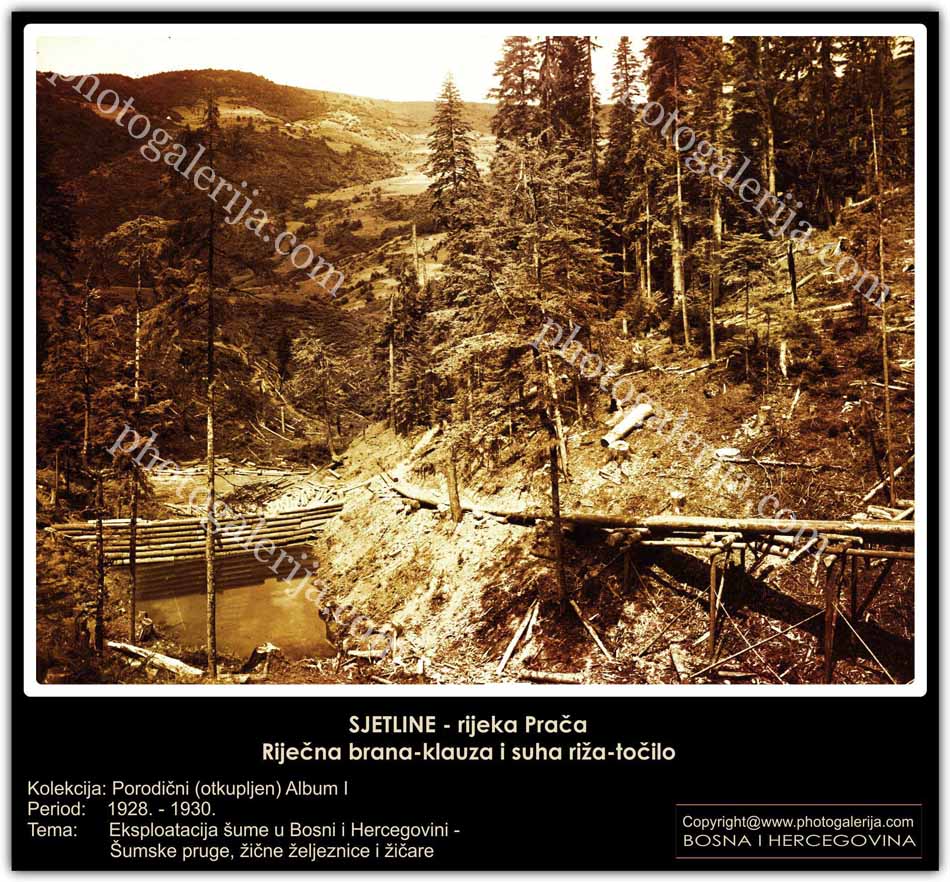

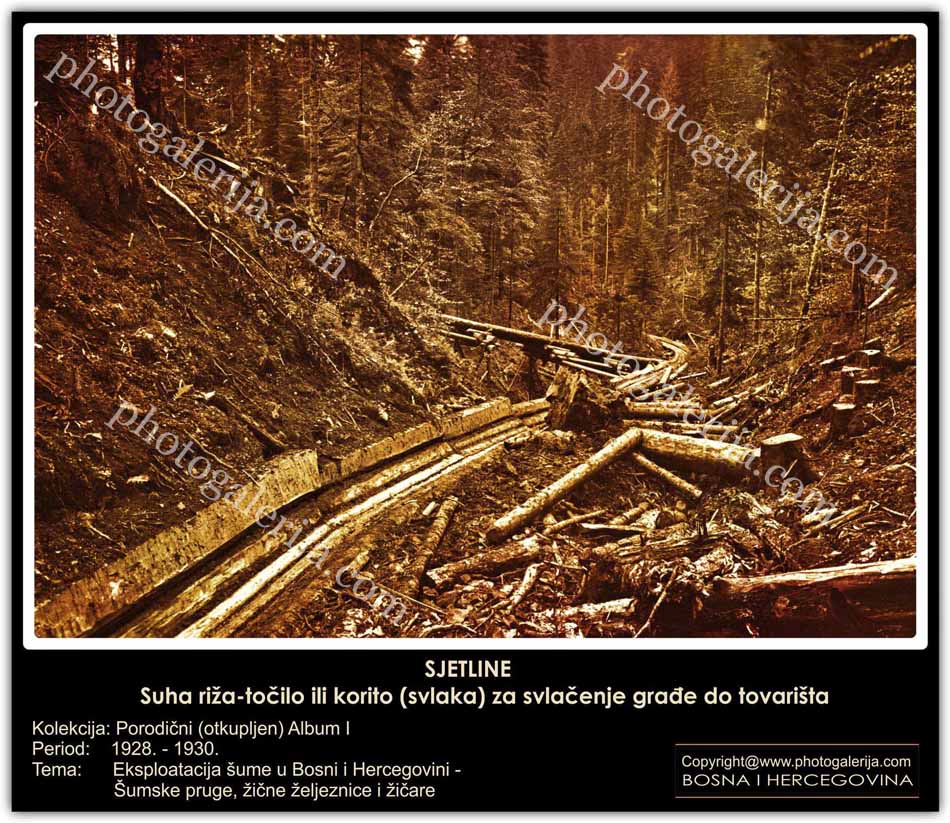

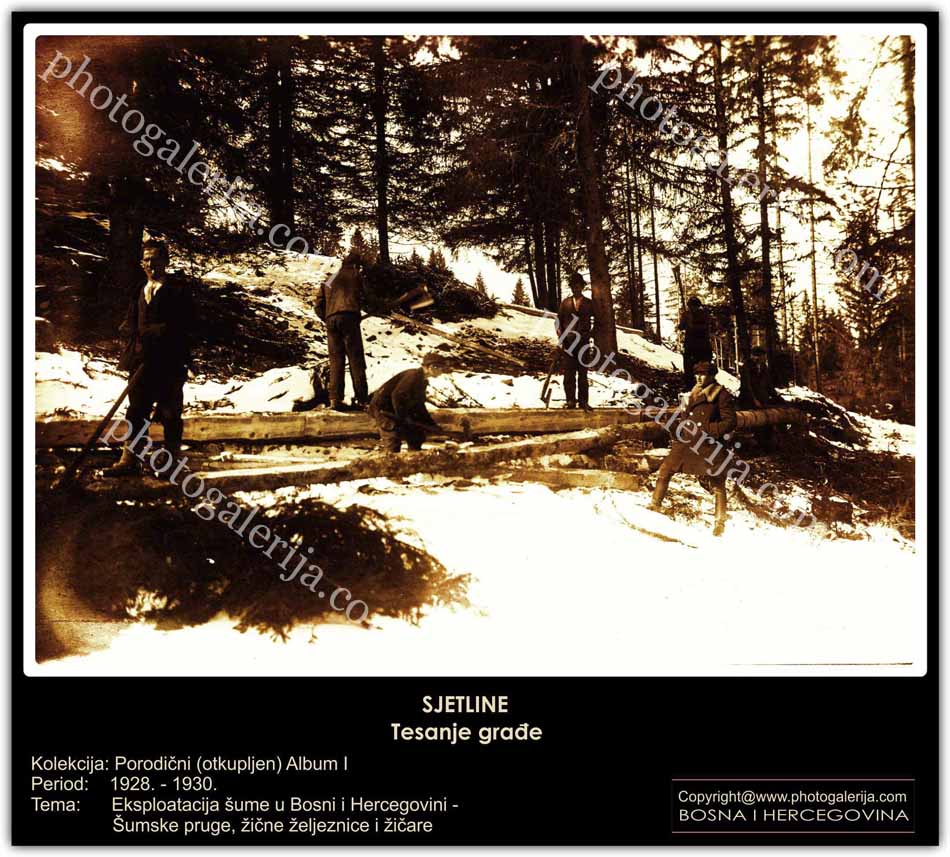

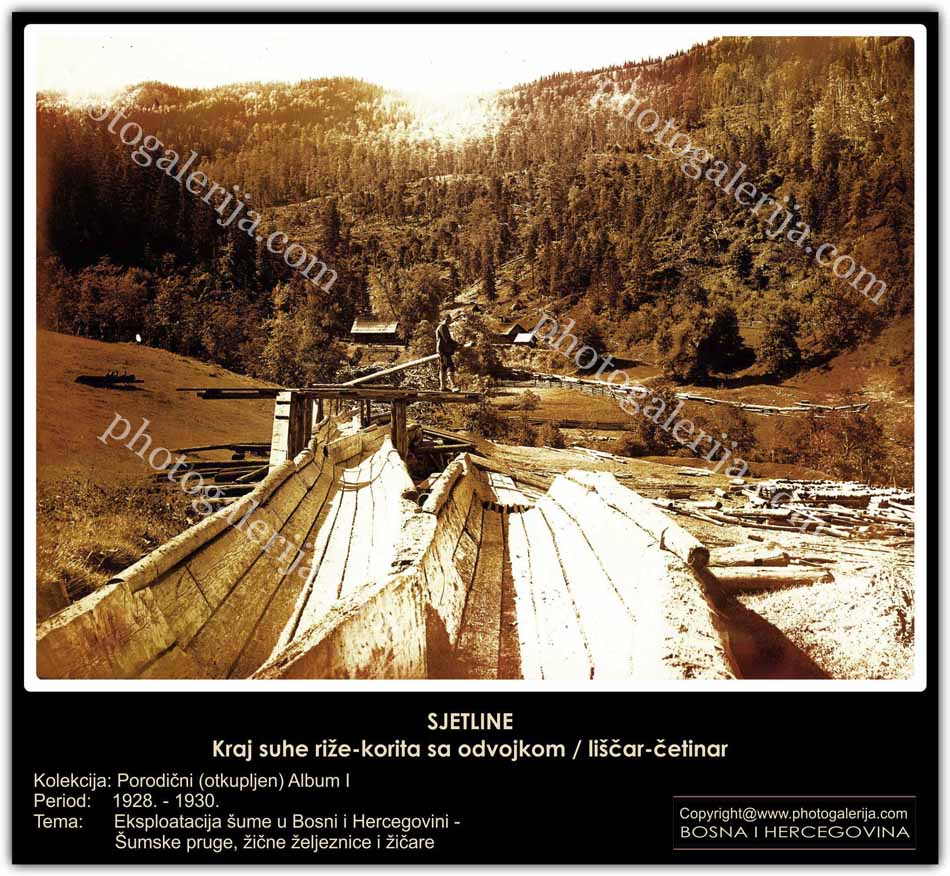

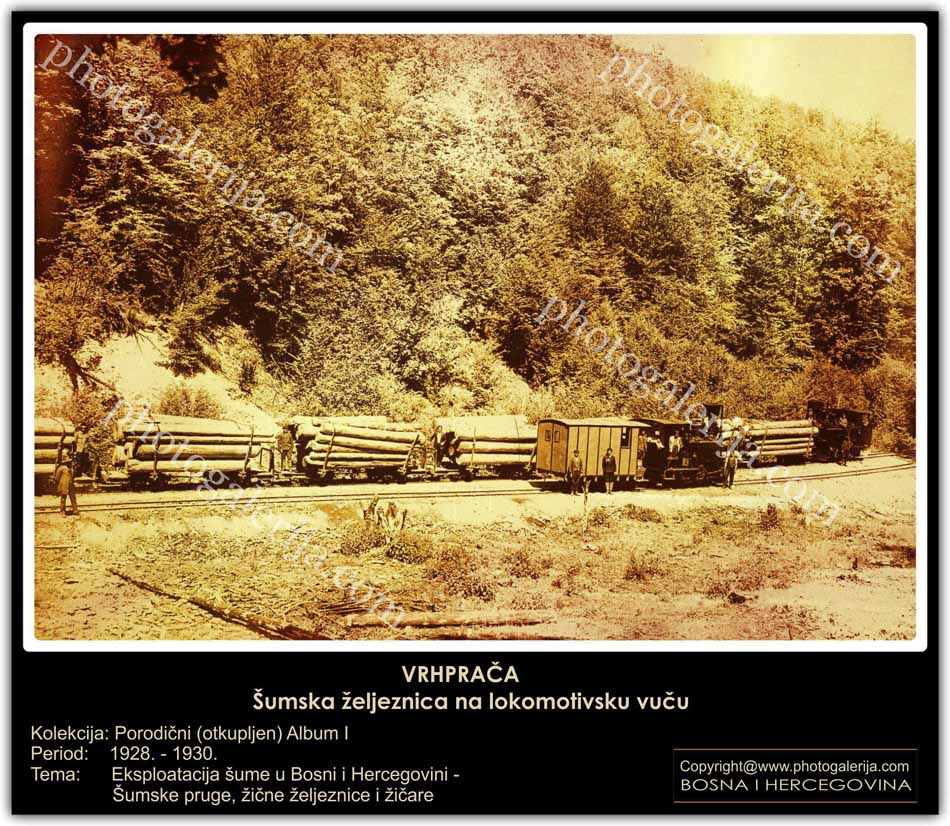

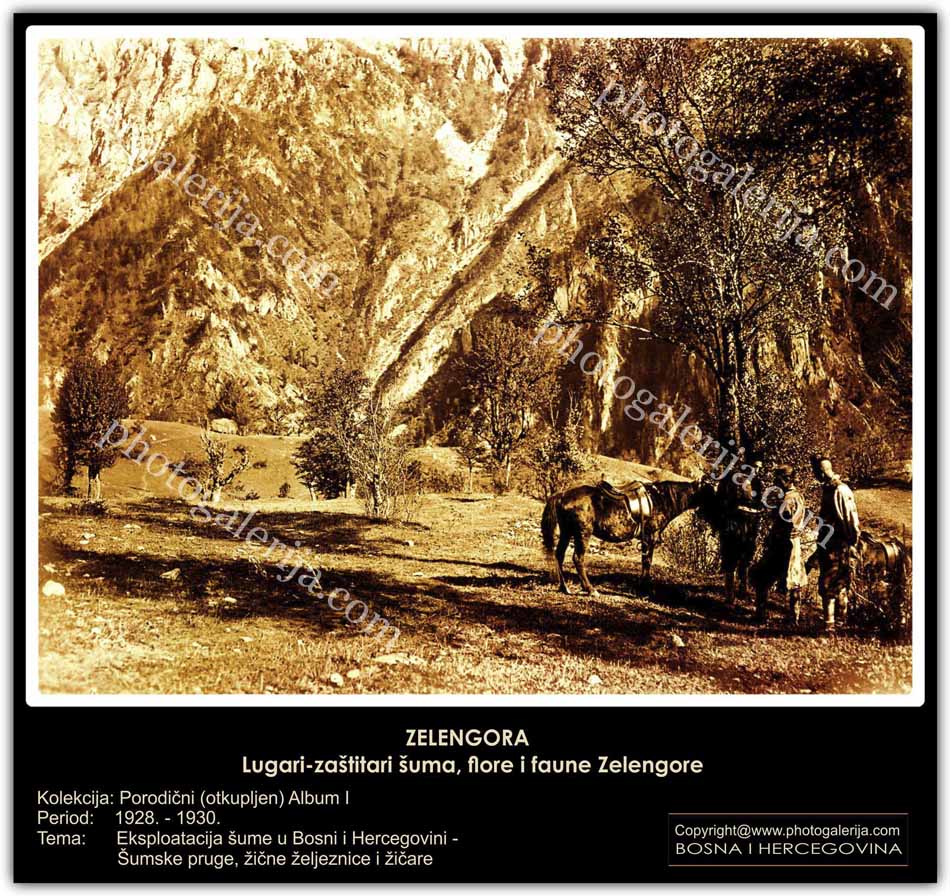

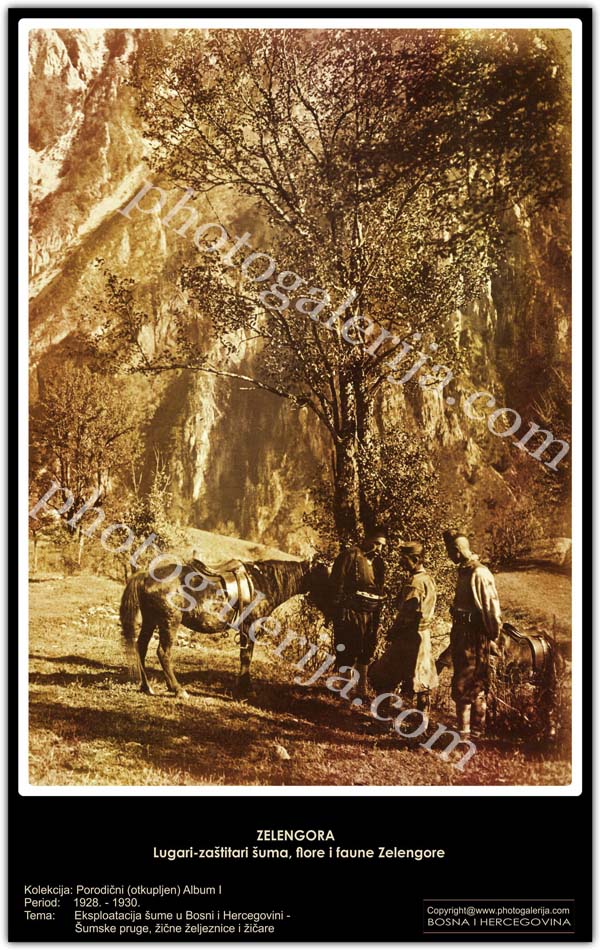

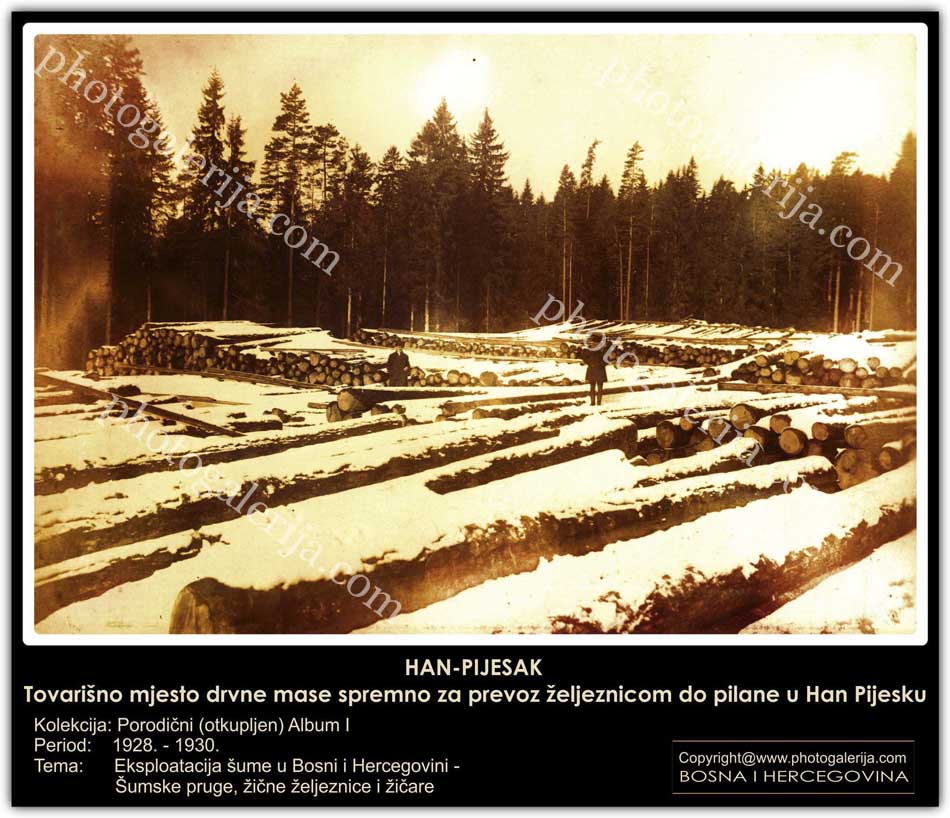

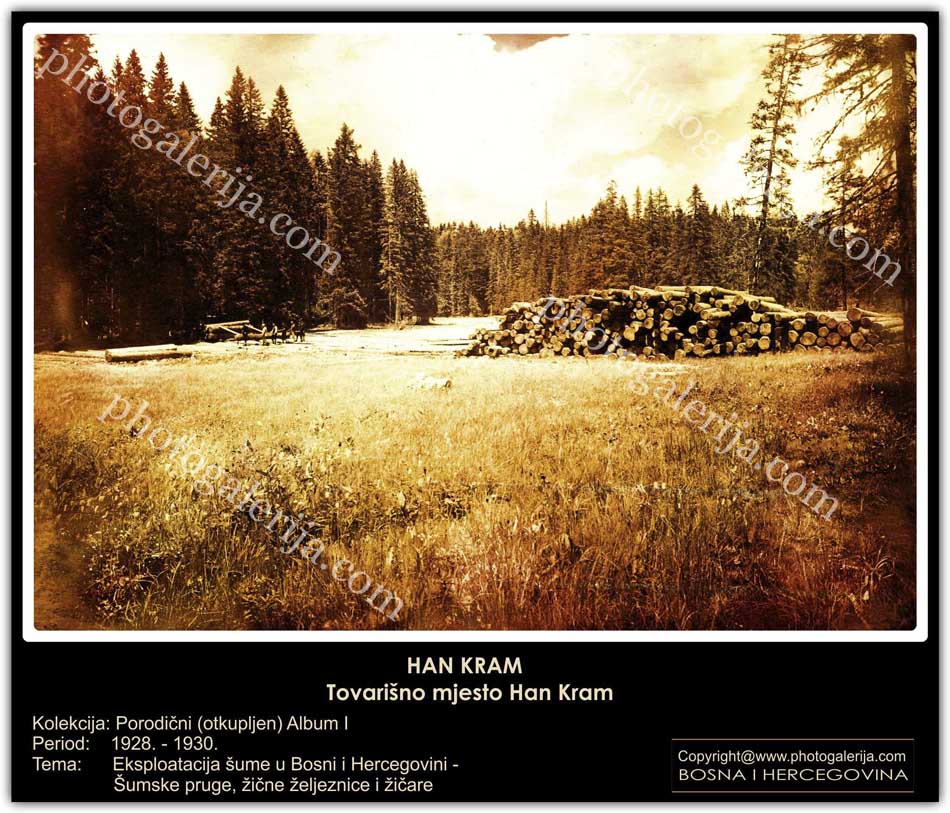

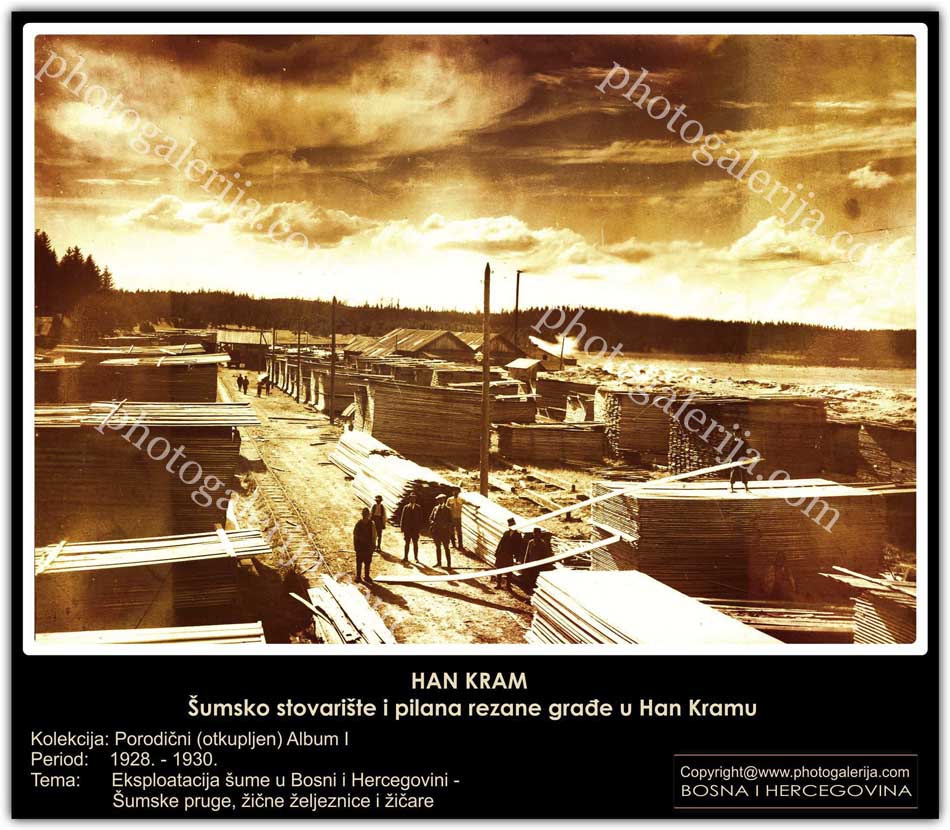

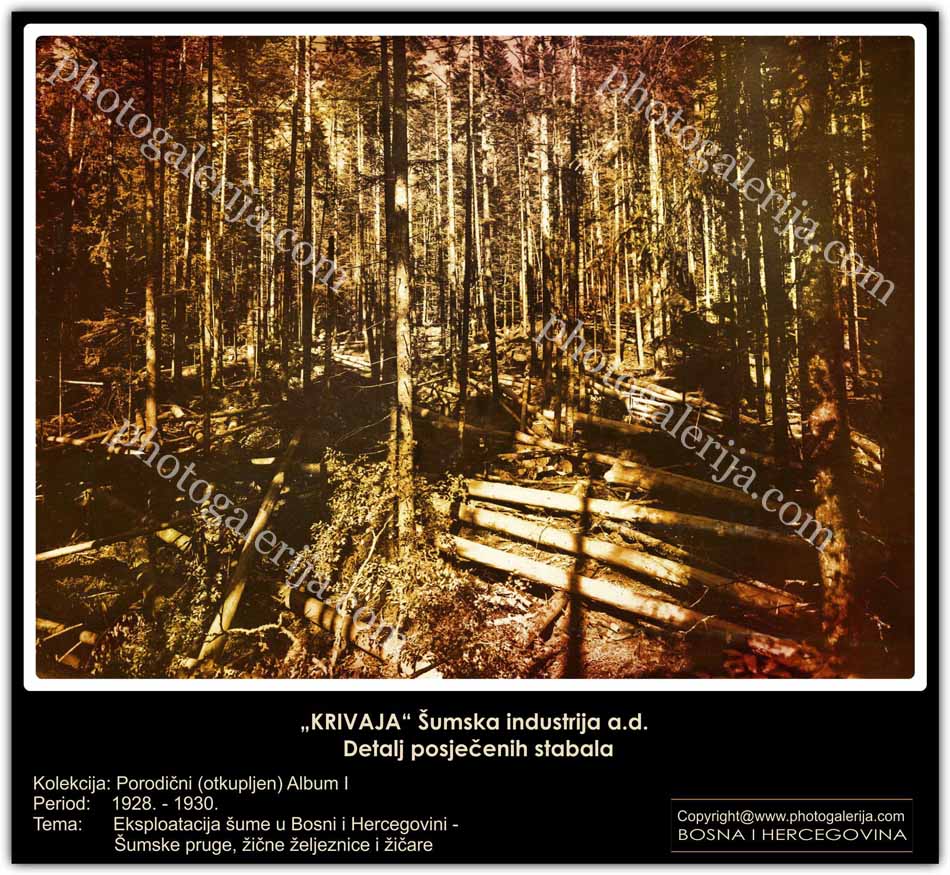

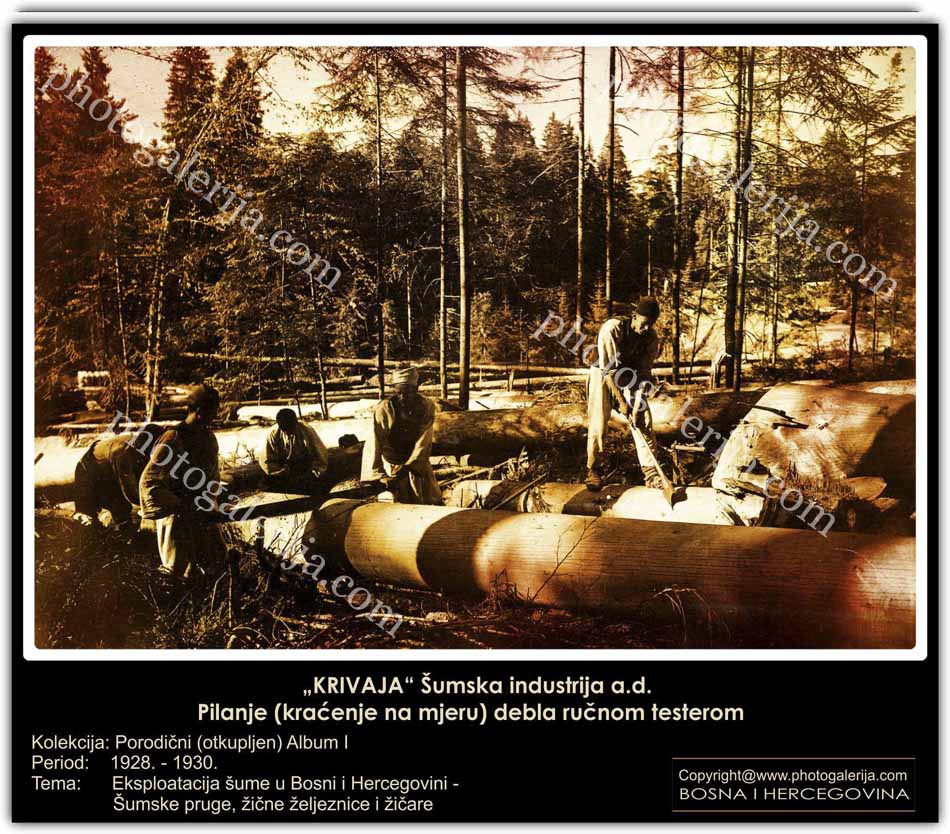

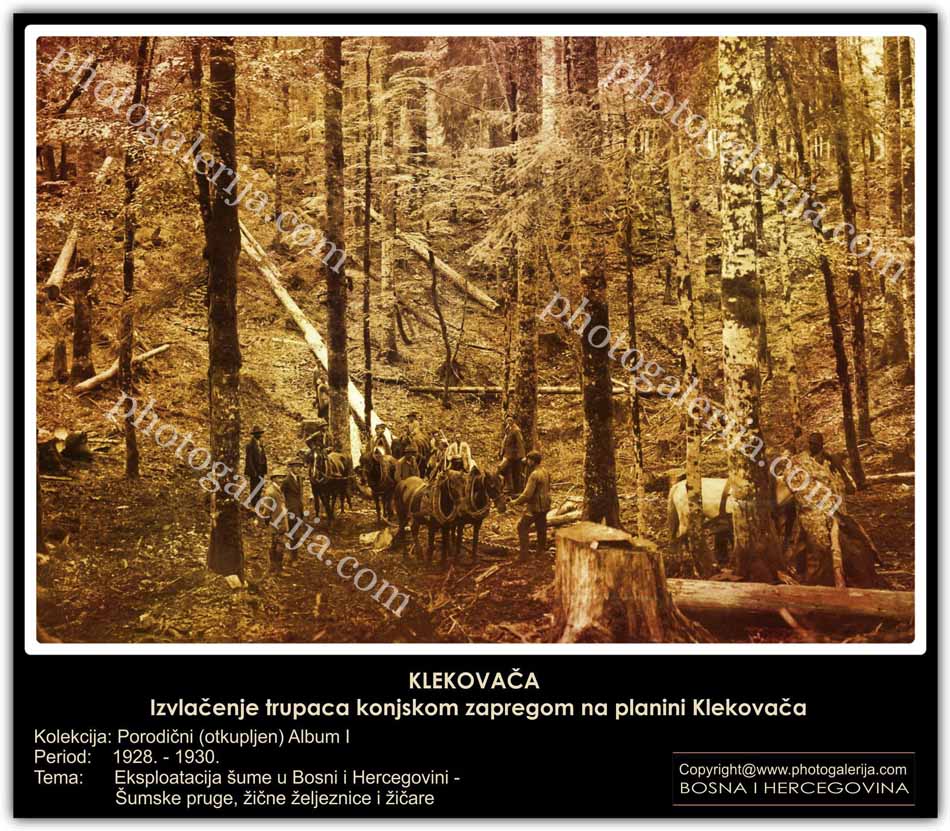

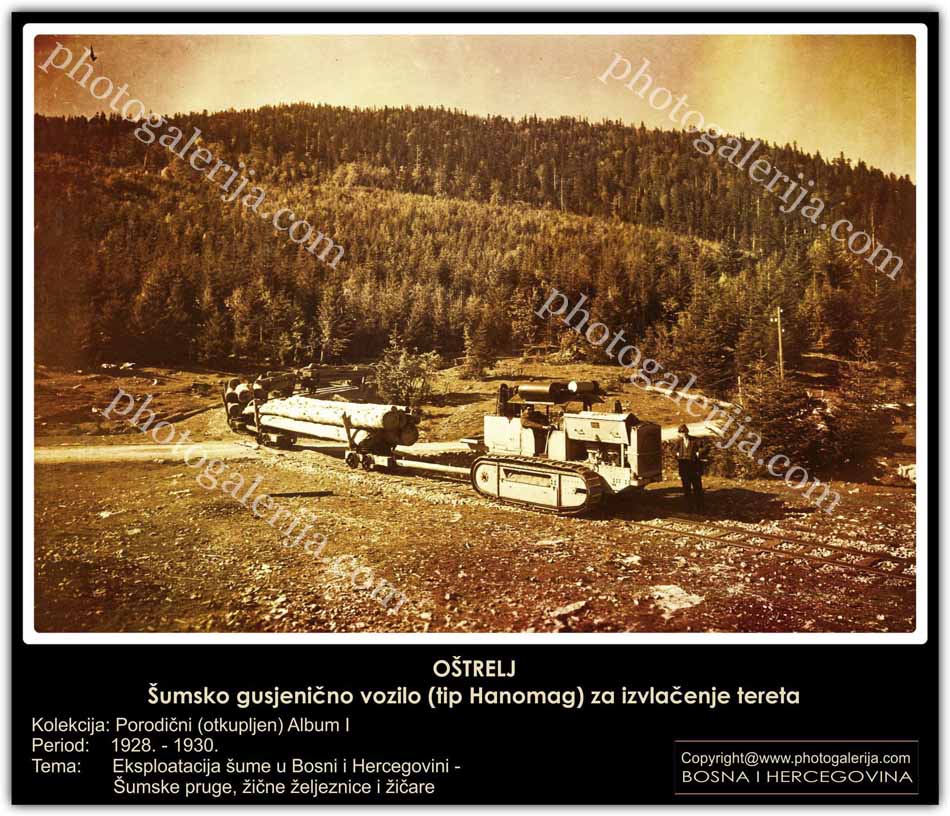

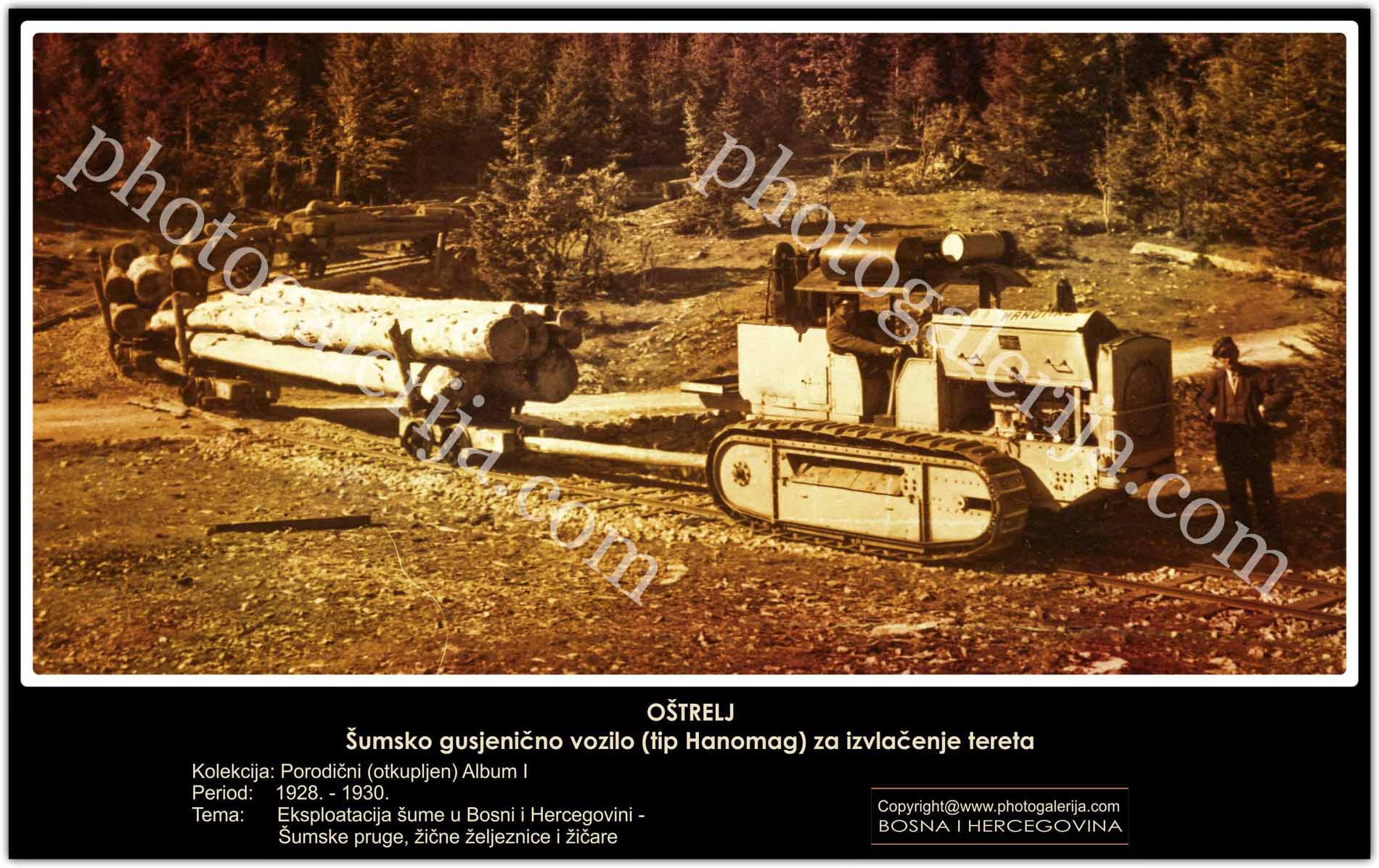

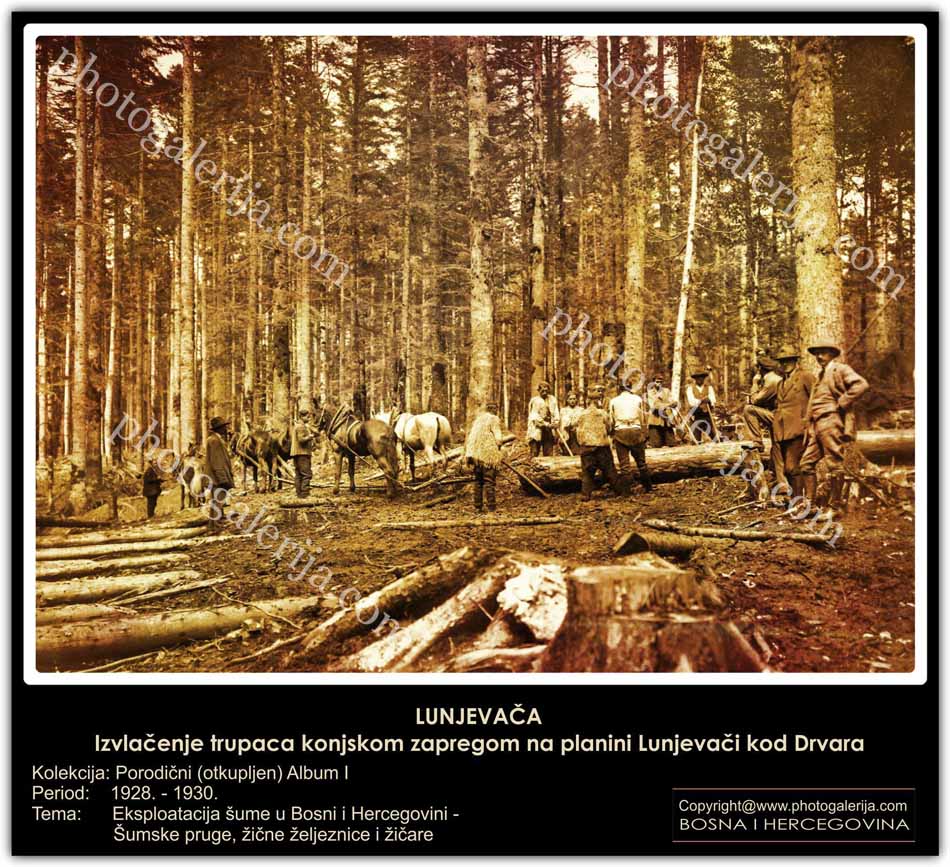

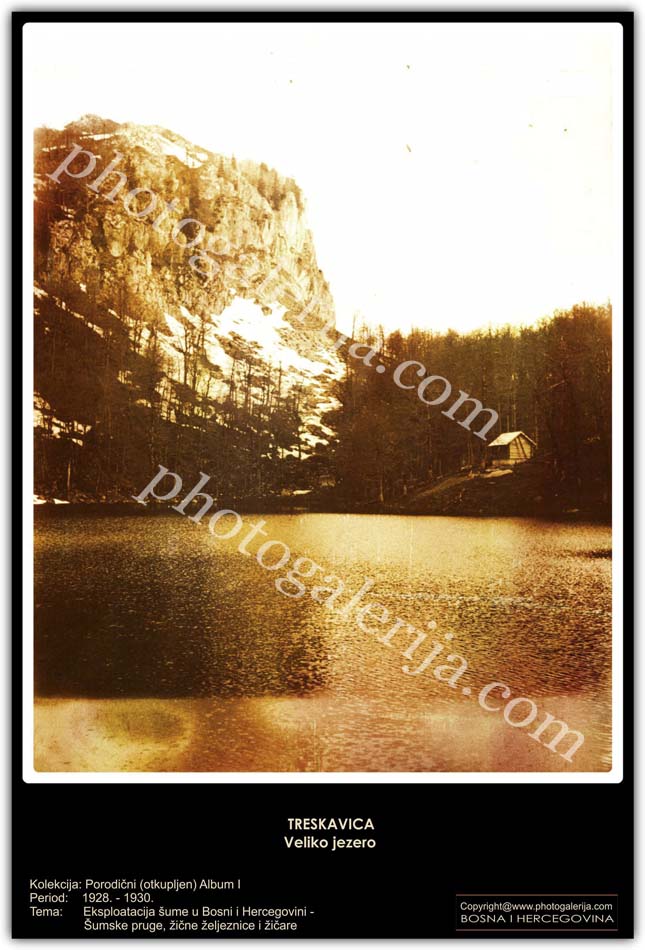

Enclosed with this article, we exclusively publish a rare collection of photographs compiled in two parts. The source of these photographs consists of two (purchased on the collector’s market) family albums created during the Kingdom of SHS-Yugoslavia from 1925 to 1933. This supplement does not diminish the importance of the topic in the upper title of the article because all the forest and narrow gauge railways, as well as industrial facilities, were inherited from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in 1918.