Introduction:

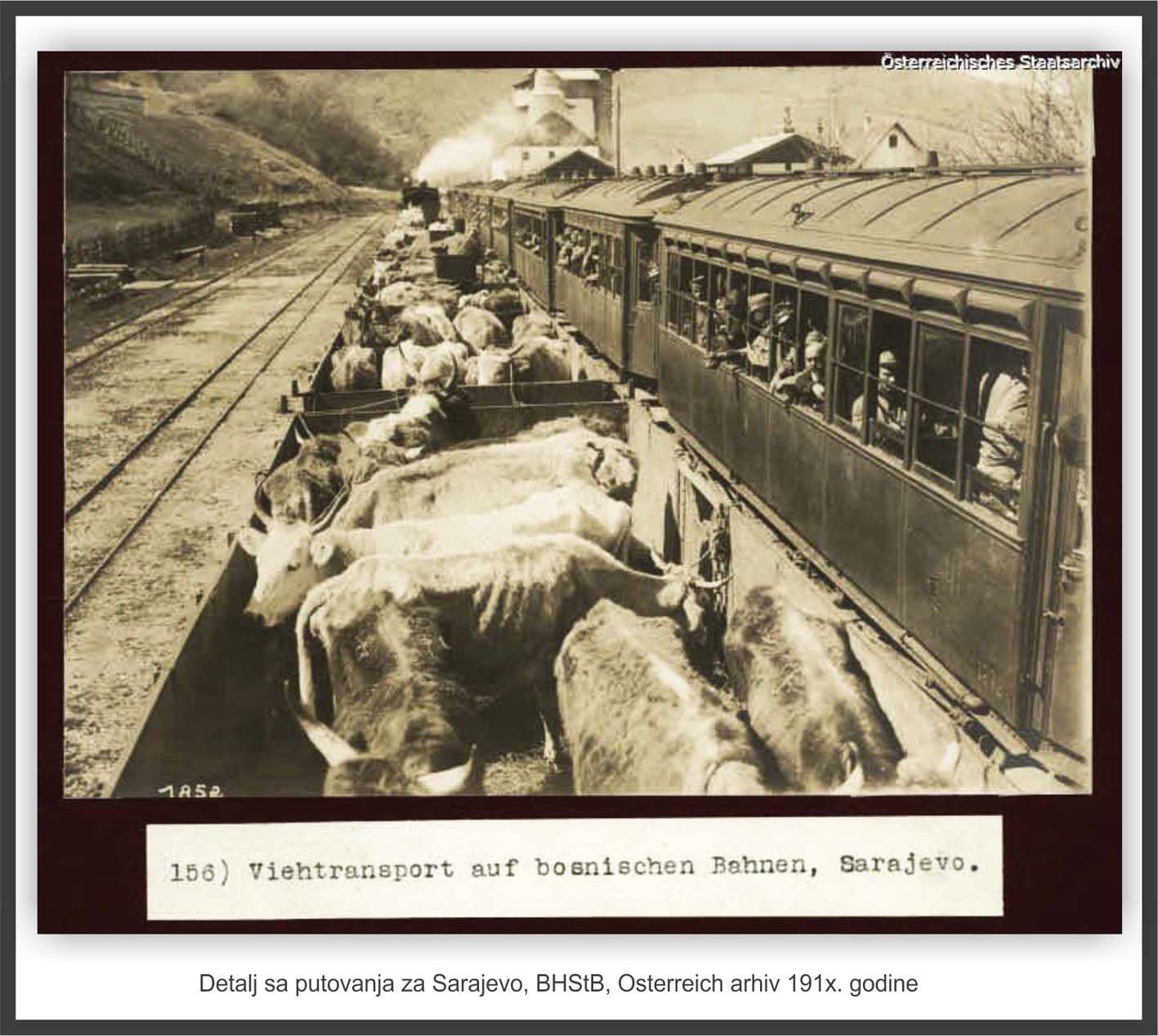

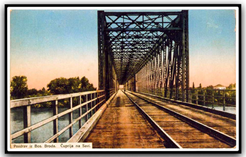

Located at the gateway of the Balkan Peninsula, at the crossroads of North – South and West – Southeast, during the Austro-Hungarian rule and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, important international routes passed through Serbia, Croatia, and even Dalmatia. These tracks were traveled by renowned trans-European trains such as the Simplon – Orient Express (London – Paris – Simplon Trieste – Belgrade – Constantinople – Athens) and the Orient Express (Paris – Berlin – Budapest – Belgrade – Bucharest – Constantinople – Athens). In addition to these luxurious long-distance trains, there was a whole array of fast international trainsAt that time, Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its narrow-gauge track, was a “blind alley” for international traffic. As it was then called, the “military railway” or “Bosnian railway,” and due to its narrow gauge of 760 mm, it was also known as the “Bosnian gauge,” the only exit to Europe (the standard-gauge main road from Belgrade to Zagreb) was at Bosanski Brod (Brod – Sarajevo in October 1882). For travelers, this was the end of their journey regardless of whether they were carriers of the imperial crown or ordinary citizens with a wooden suitcase. The Bosanski Brod station (built in 1896) had two stations, one for narrow gauge and one for standard gauge. Only in 1915, through the integration of the narrow and standard gauge, was local traffic established across the railway bridge to Slavonski Brod.

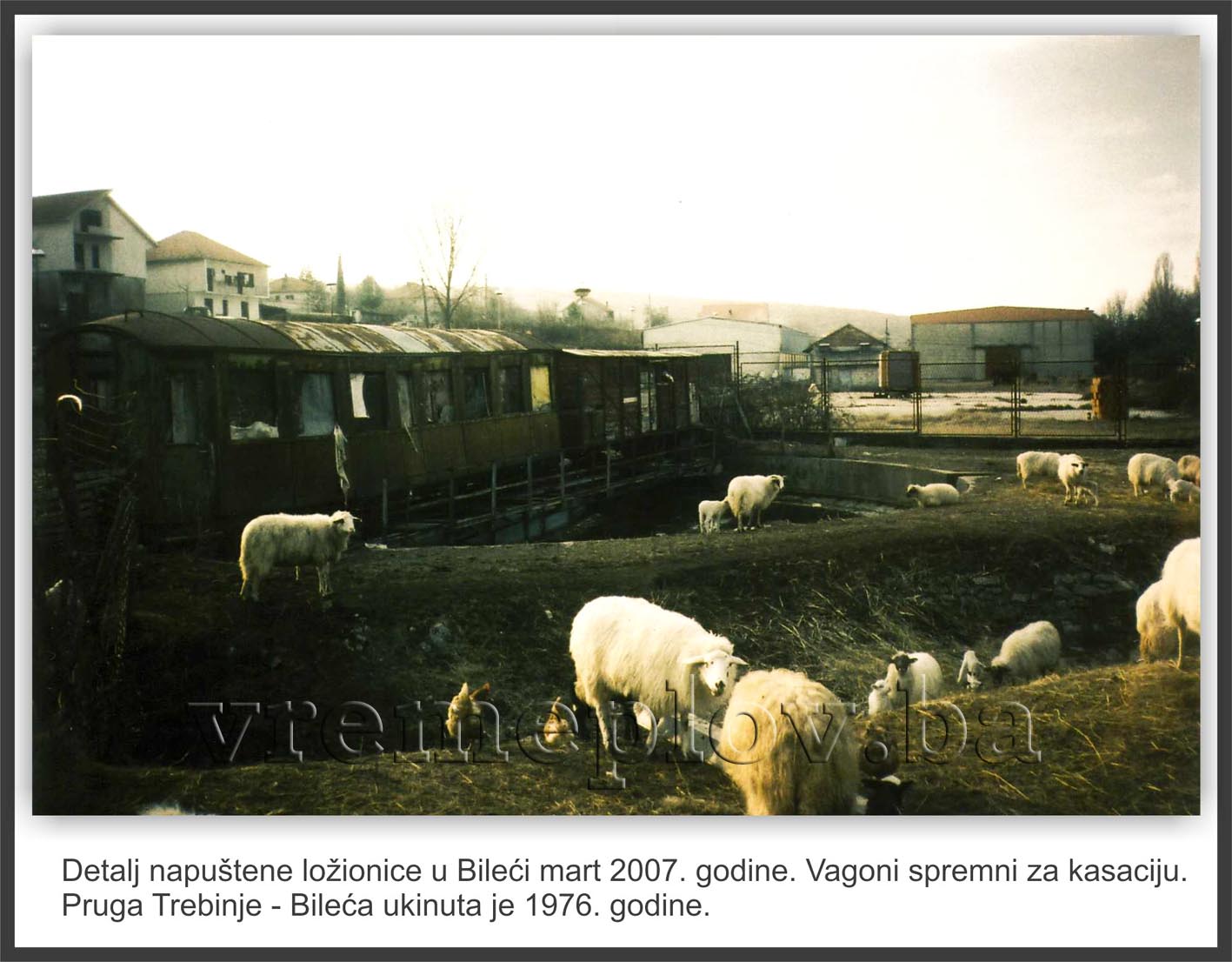

The second railway connection with narrow gauge from Bosnia was established with the opening of the line Gabela – Hum – Uskoplje – Dubrovnik and Uskoplje – Zelenika for public traffic in 1901 (the so-called Herzegovina-Dalmatian railway). The third outlet, in 1914, was enabled by the commissioning of the narrow gauge Prijedor – Knin line (Steinbeis Railway from 1892, later Šipad Railway), and from Knin, travelers continued by standard gauge to Šibenik and Split. The fourth route was established on the Sarajevo – Belgrade line in the summer of 1931, with a direct line Belgrade – Sarajevo – Dubrovnik in the summer of 1938. The connection to Montenegro (Hum – Trebinje – Bileća – Nikšić) was made by constructing the narrow gauge railway from Bileća to Nikšić in July 1938, and in July 1948, with standard gauge to Podgorica (formerly Titograd).

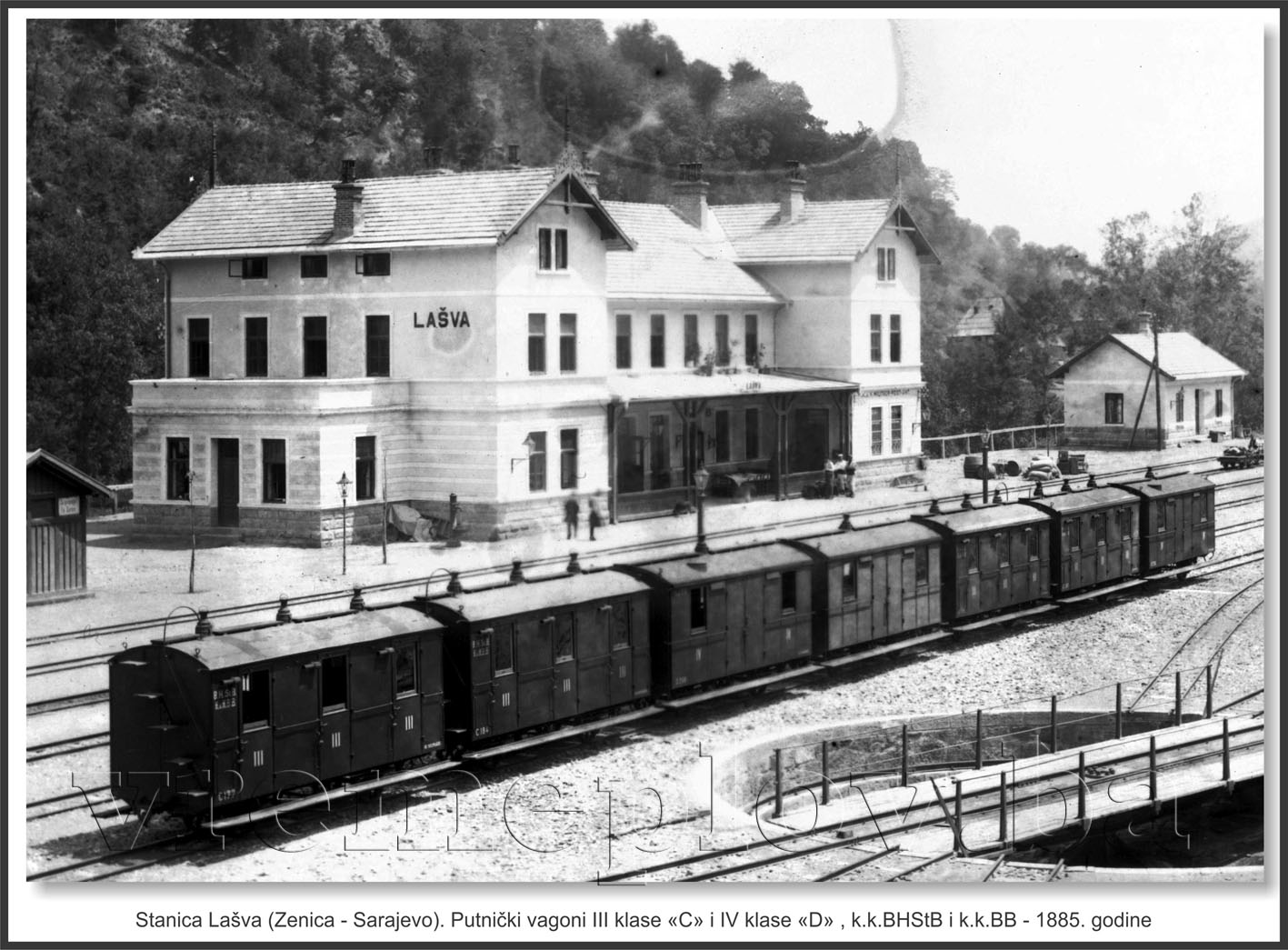

Since the topic is the narrow gauge railway, it should still be mentioned that the only direct route for travel to Europe could be realized by the standard gauge line Banja Luka – Dobrljin – Zagreb (1872). This line was not practical, except for adventurers, because a traveler from Herzegovina (Metković – Sarajevo August 1891) would change trains in Sarajevo, then travel by a new train to Lašva station, and again transfer to a new train on the Lašva – Jajce line (May 1895). From Jajce to Banja Luka, travel was by road using a passenger car or omnibus with a horse-drawn carriage.

The First Passenger Railway Traffic in Bosnia and Herzegovina

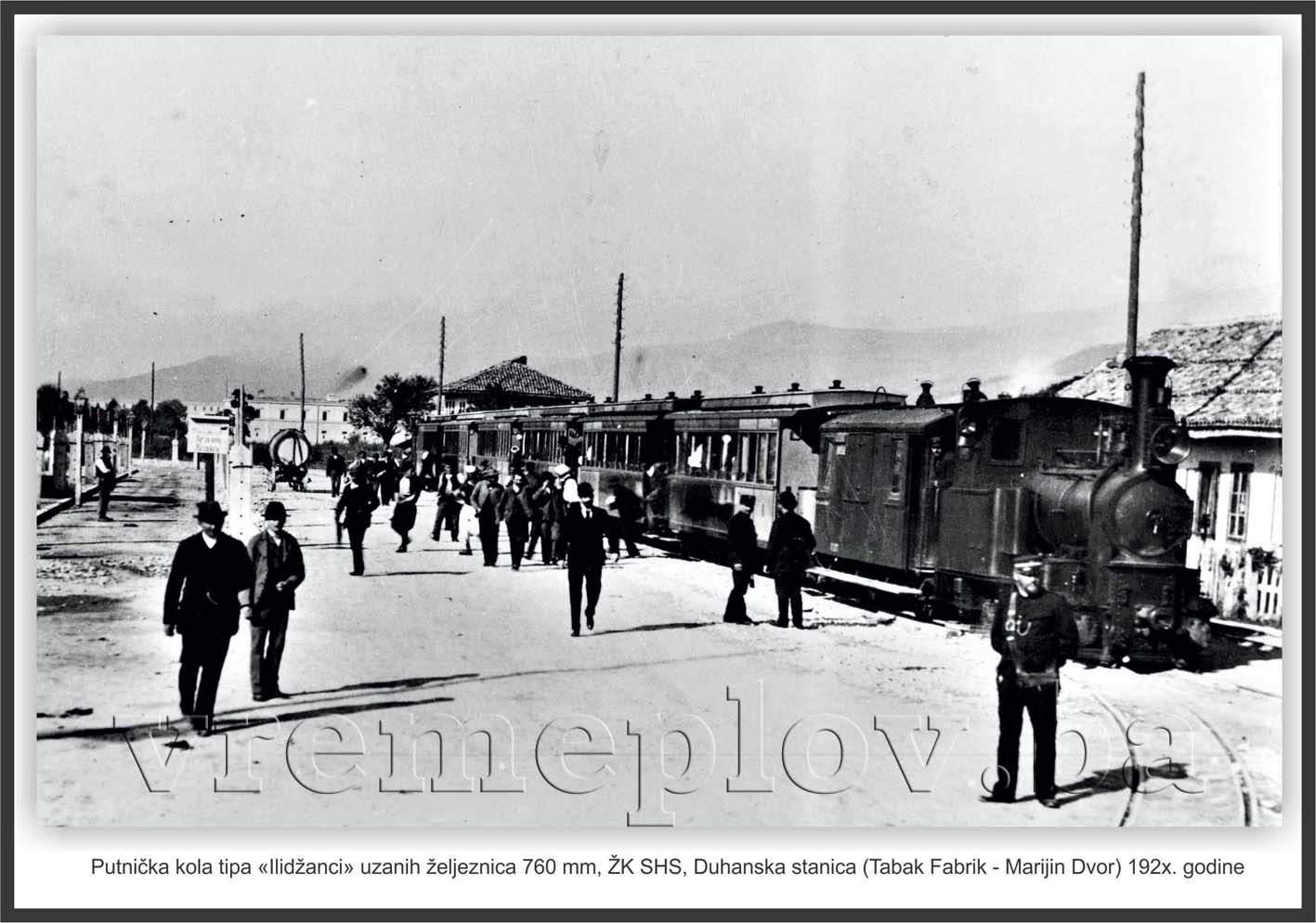

The first passenger train service was established with the construction of the narrow gauge line from Bosanski Brod to Zenica, as the first railway in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was put into public transportation on July 14, 1879, and that day is considered the birthday of the railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina. We note that this day was never and nowhere celebrated, but instead October 5 was commemorated as the day of the first train arriving in Sarajevo in 1882. October 5 was officially recorded as the day the railway was opened to the public, while the first train from Zenica arrived ceremoniously on October 4, 1882.

Namely, according to a written chronicle from the newspaper “Sarajevski list” dated October 4, 1882, we share a few quotes: … “Since on Monday and politically they examined the new track from Zenica to Sarajevo, it was decided for today, on the eve of the holiday of our beloved ruler Franz Joseph, that the first ceremonial train from Sarajevo would depart to Zenica and back.” … “This morning, the Sarajevo station gleamed in its full glory, decorated with flags and greenery, and on the new platforms stood a long train with newly built carriages and with flags and banners, topped with a locomotive decorated with flags.” A large number of passengers were at the station to bid farewell to the first train with heartfelt wishes… “At 7 o’clock, His Excellency Mr. Baron Appel arrived at the station in a parade carriage and occupied a place with the Marshal of the Army Stransky, Mr. Komadin, and Colonel Pittreich from the War Ministry.” … “There were up to 120 passengers in the train. Exactly at 7 o’clock, the train set off amid the humming of music that was arranged in the front carriages.” … “With the journey and stops at stations, of which there are only eight to Zenica, the journey from Sarajevo to Zenica lasted only 4 hours and 25 minutes.” … “The stay in Zenica was limited to one hour, and the time passed quickly during this refreshment. When the train, with lively music, started back from Zenica, many relics along the track greeted it with long shouts, and the workers again stoked the boilers, making the air burst with smoke.” … “Thus, this continued along the entire return route, and when the train arrived at the scheduled time, five minutes before 5 o’clock, in Sarajevo, it was greeted by a crowd of several thousand people covering the entire station.”

First series of narrow-gauge passenger wagons

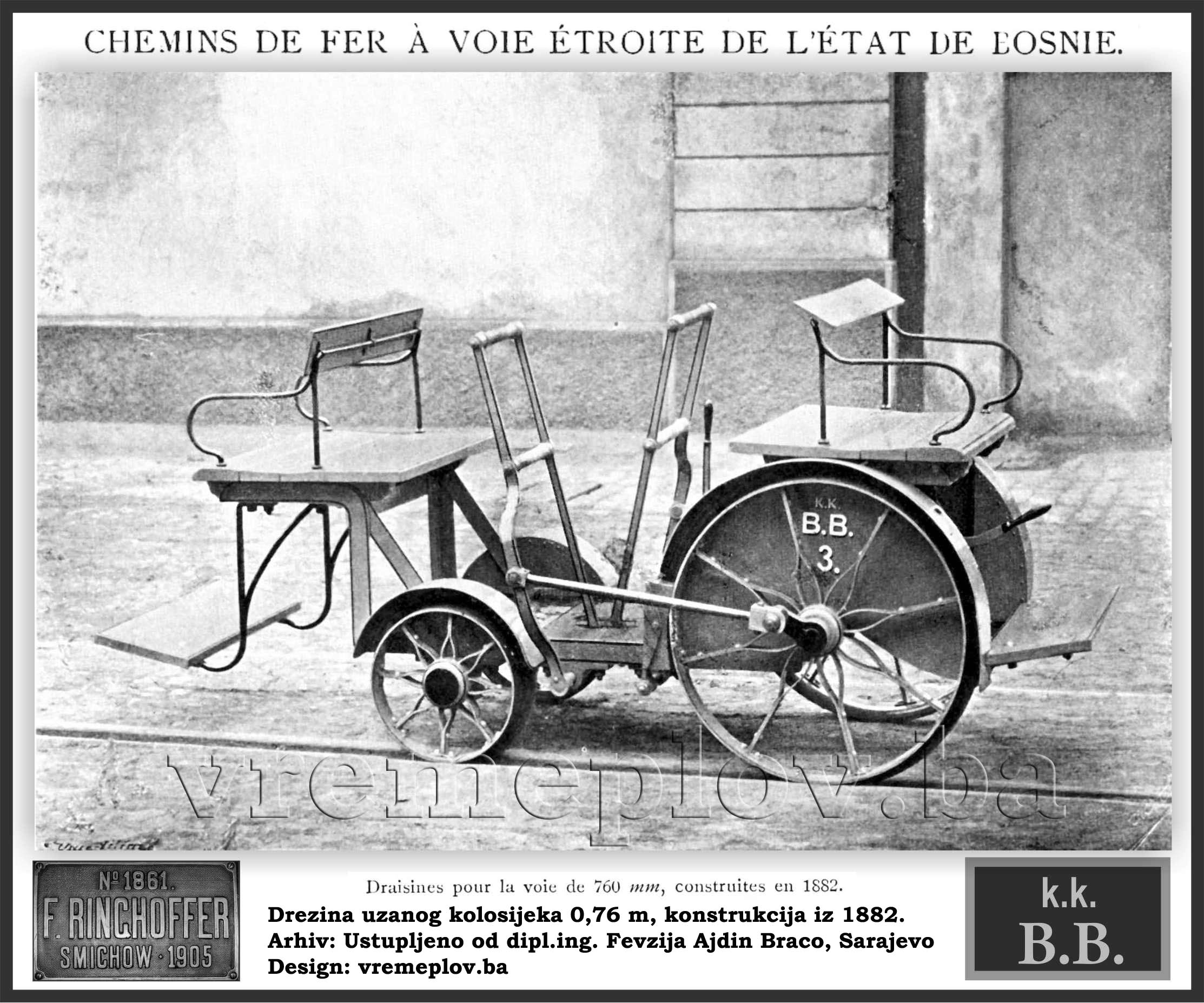

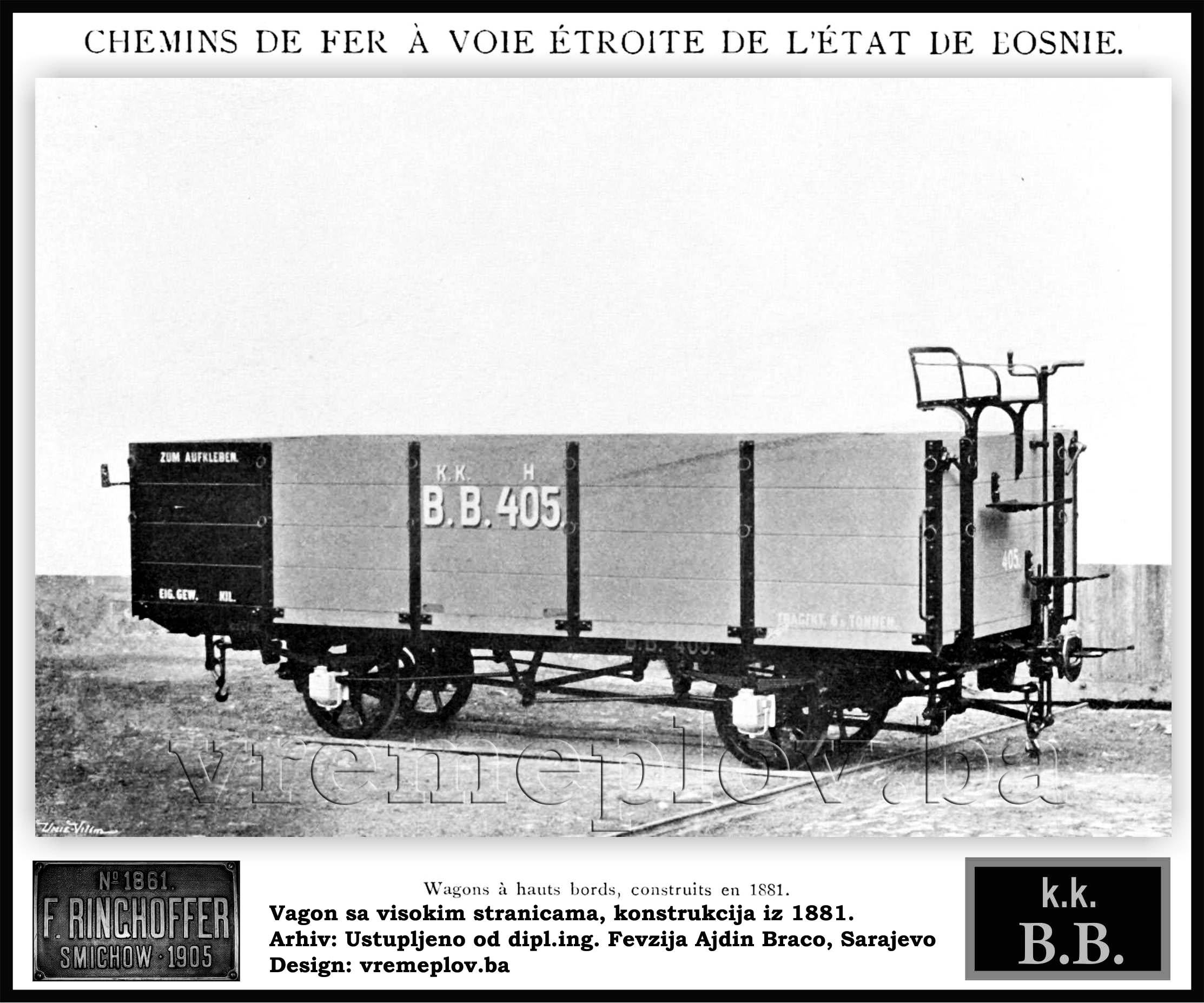

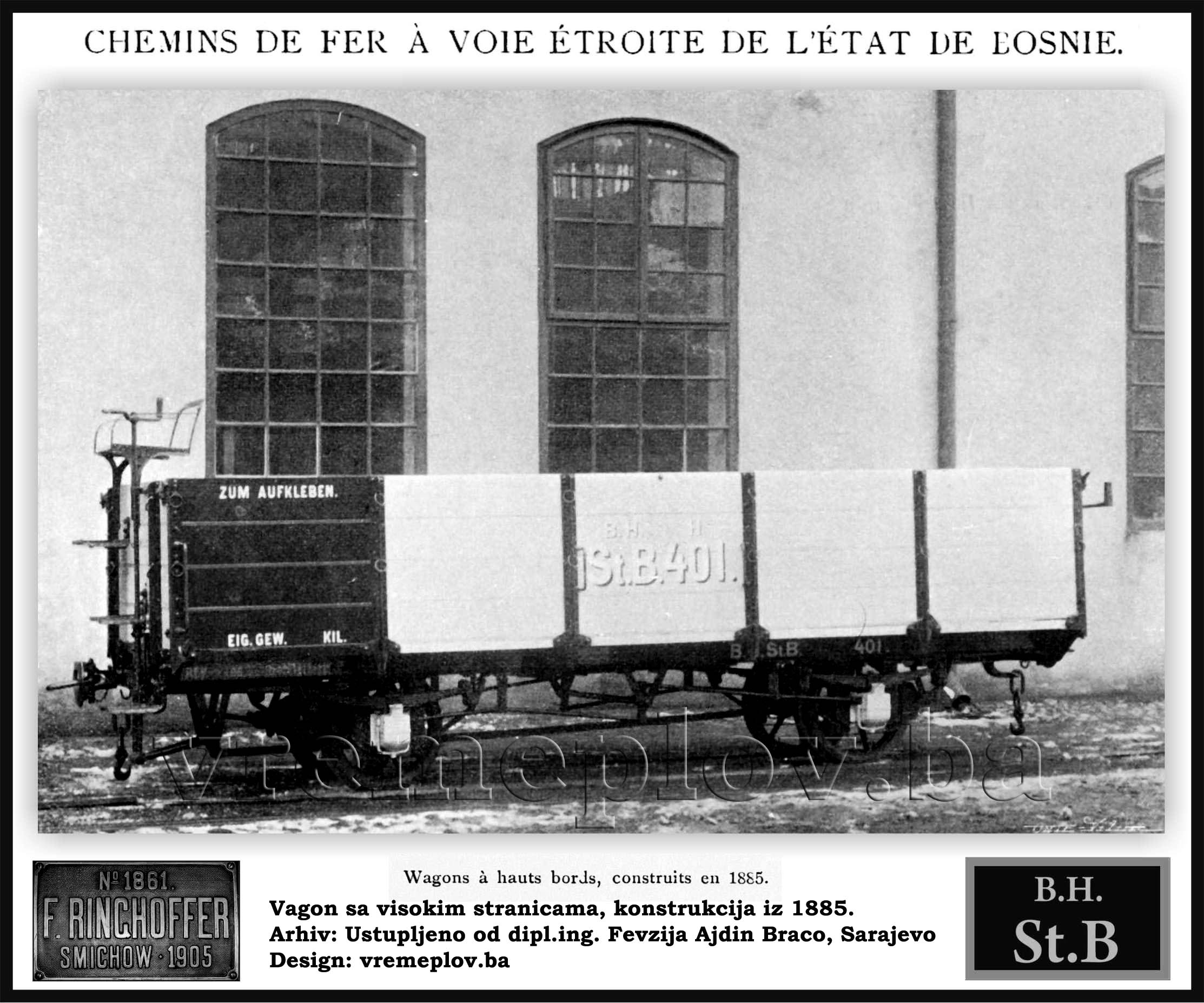

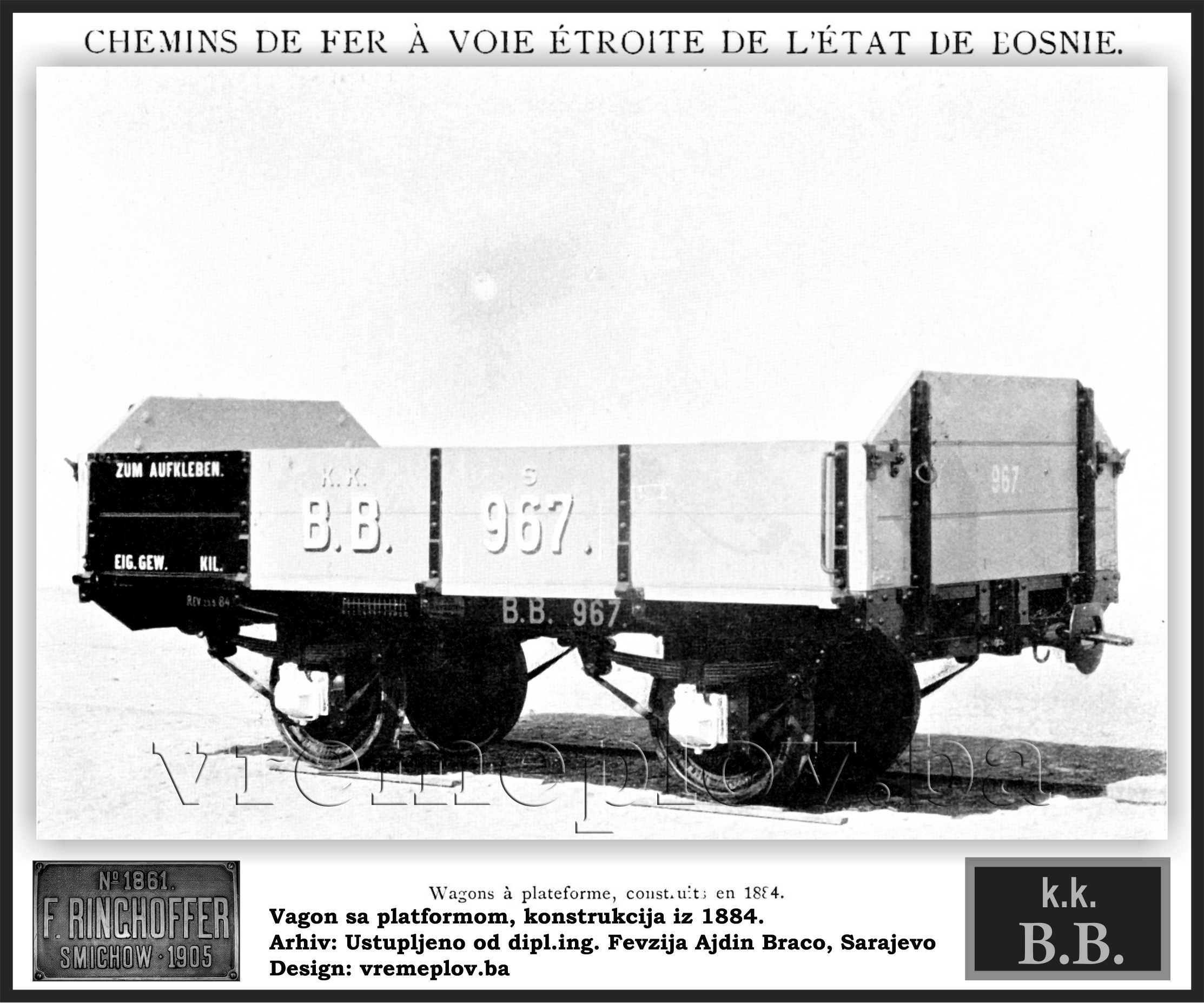

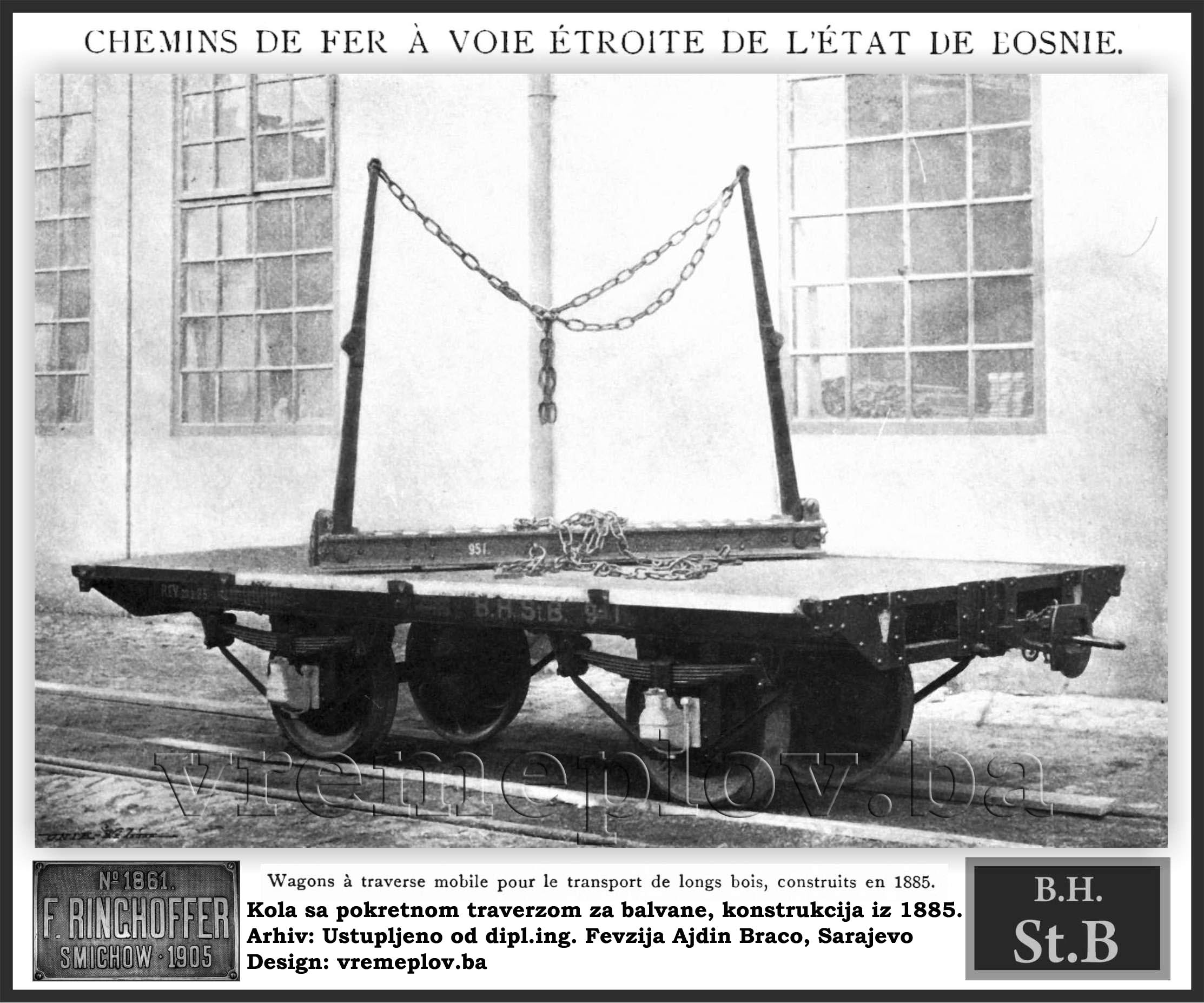

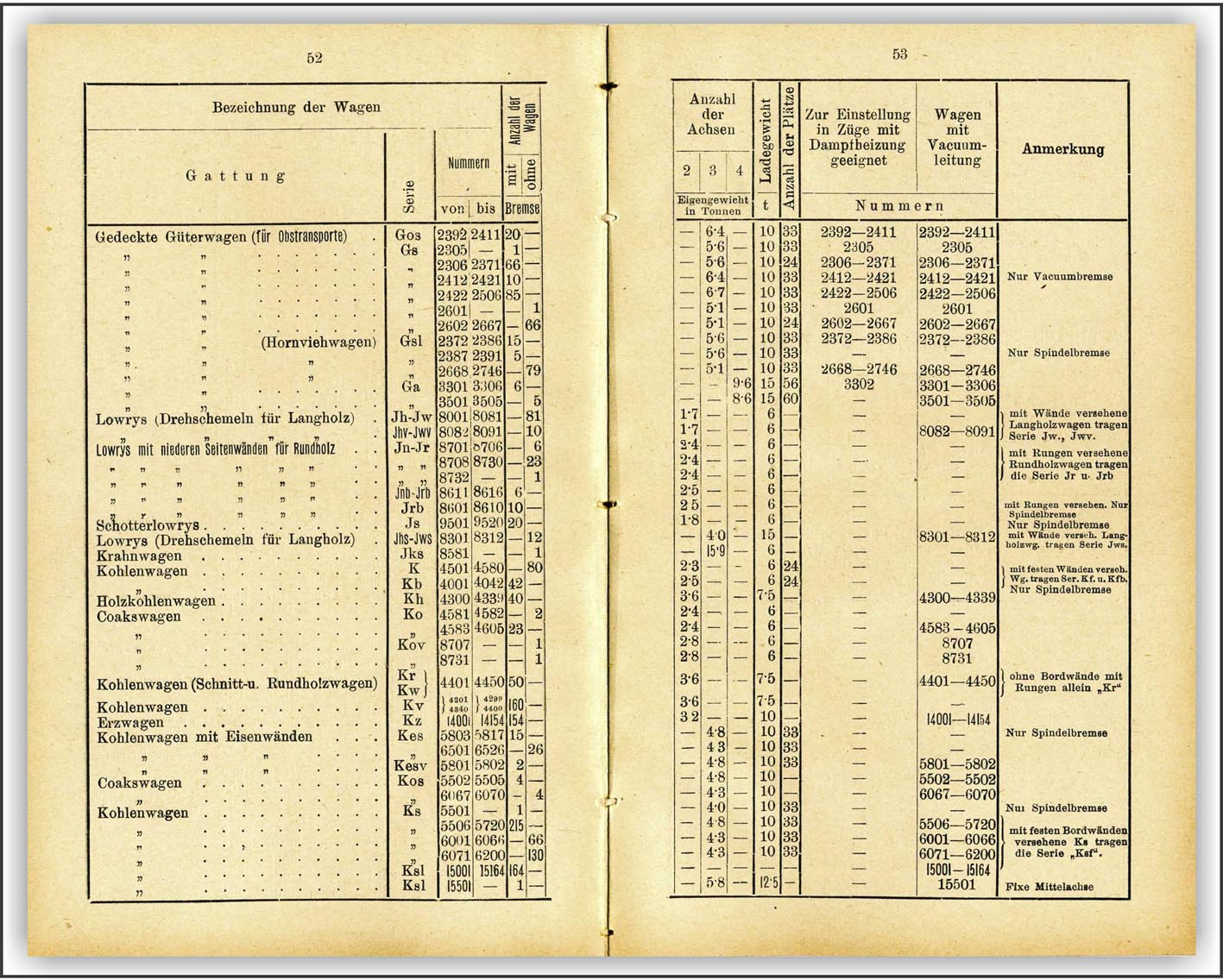

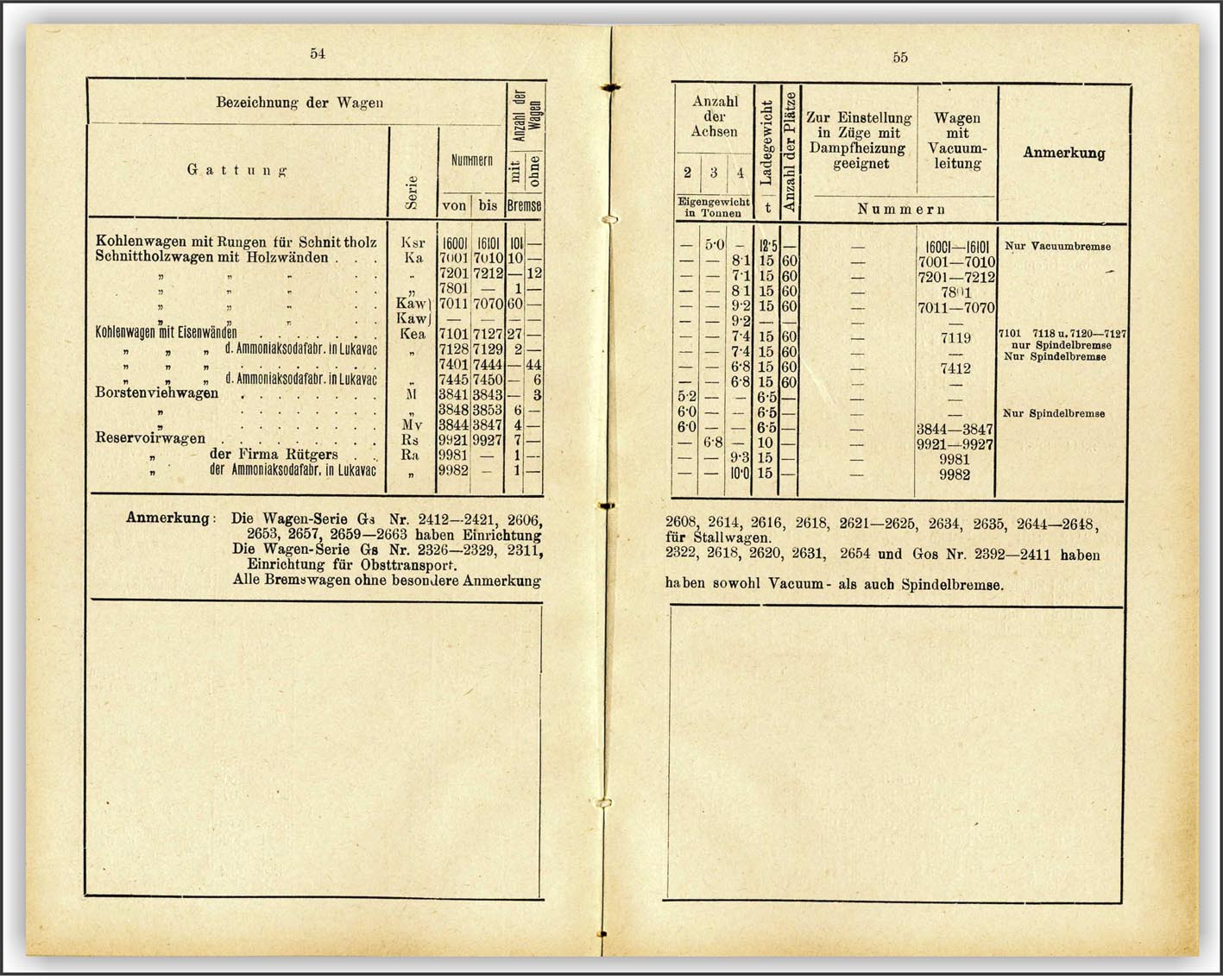

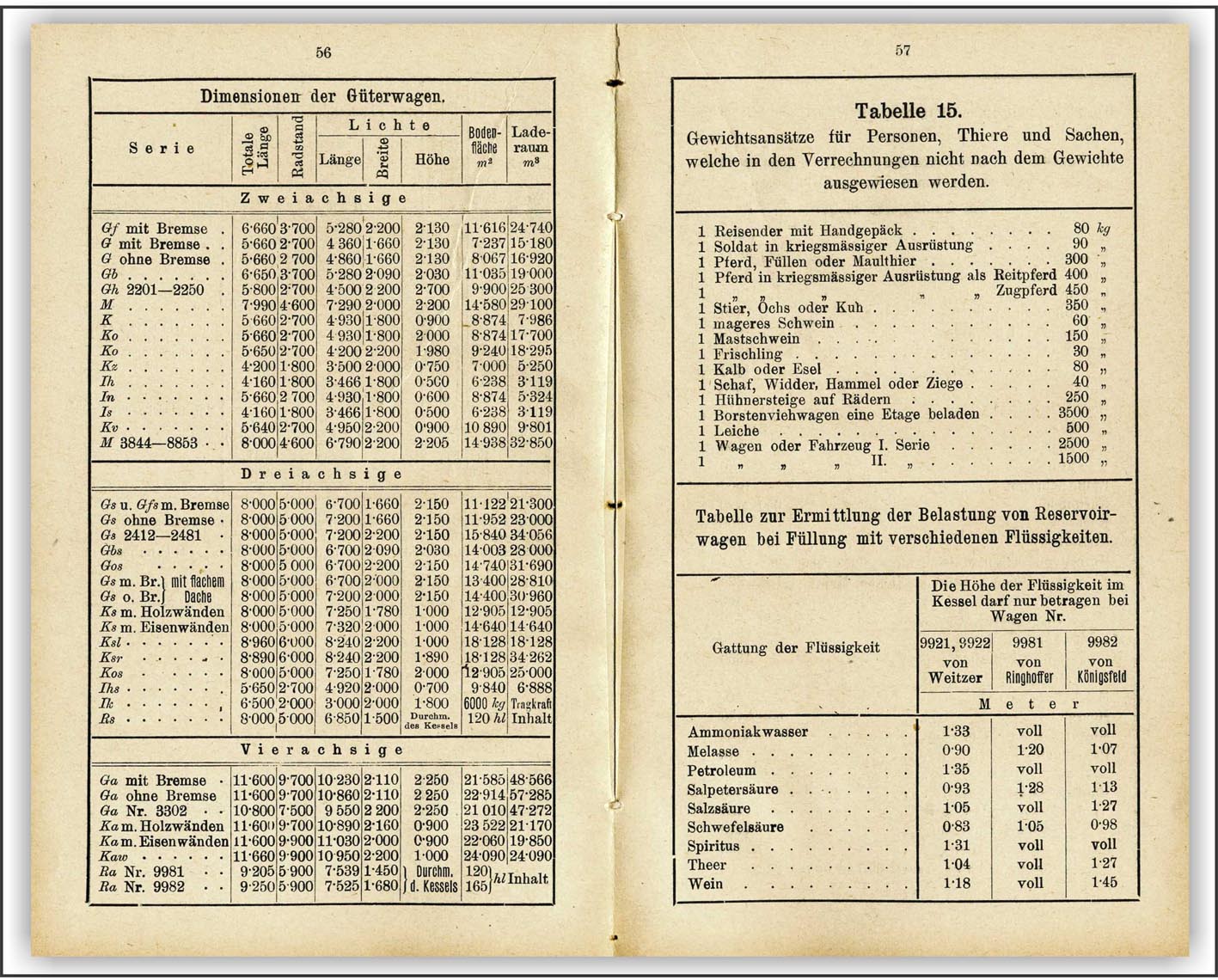

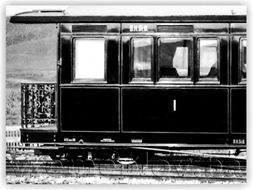

In the early years, the constructed railway served military and strategic purposes, mainly the extraction of cheap raw materials toward industrial centers. The rolling stock consisted of 20 locomotives with a power of 20 to 40 horsepower and nearly 400 small open, two-axle freight wagons called “Lorisi” (“Lowrys” in German), with a capacity of 2 tons, with primitive coupling methods. For passenger traffic, 10 “Loris” wagons were converted into passenger carriages. They were so primitive that they resembled roadside mail carts, with roof fabric stretched across four wooden posts at the corners of the wagon, the front side enclosed with planks, and curtains hanging from the roof to the front planks. Travel, even under the best conditions from Brod to Zenica (186 km), took about 15 hours.

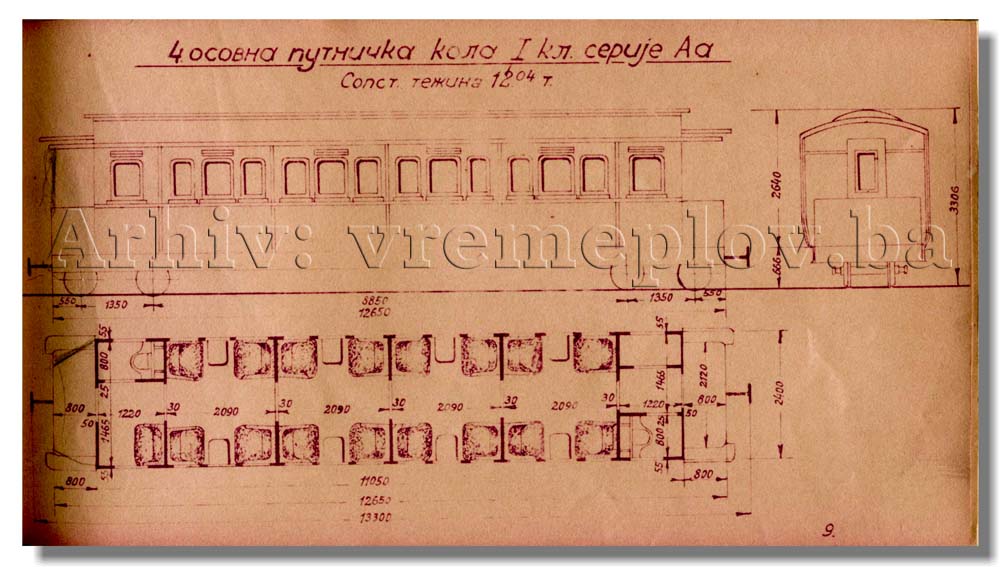

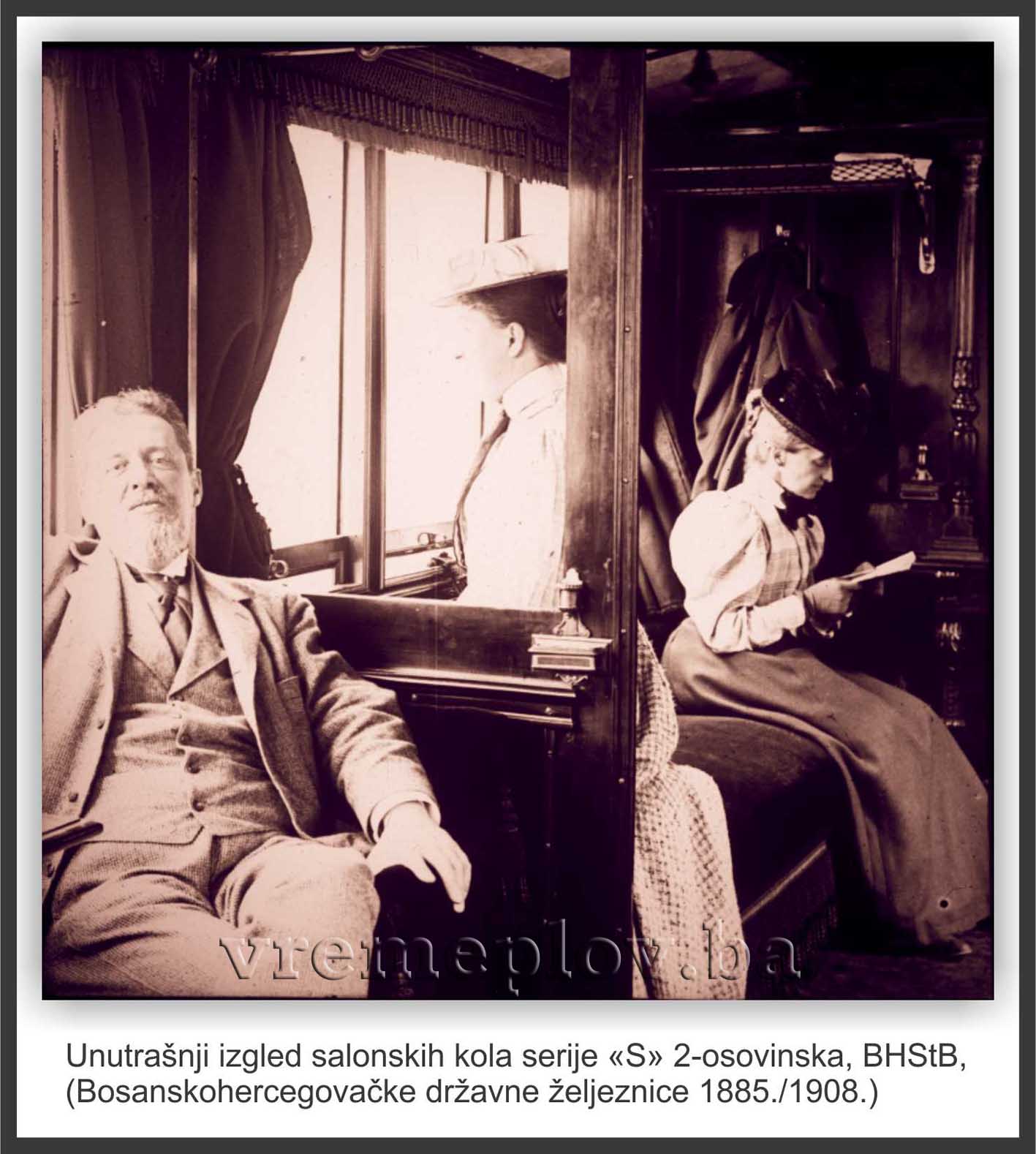

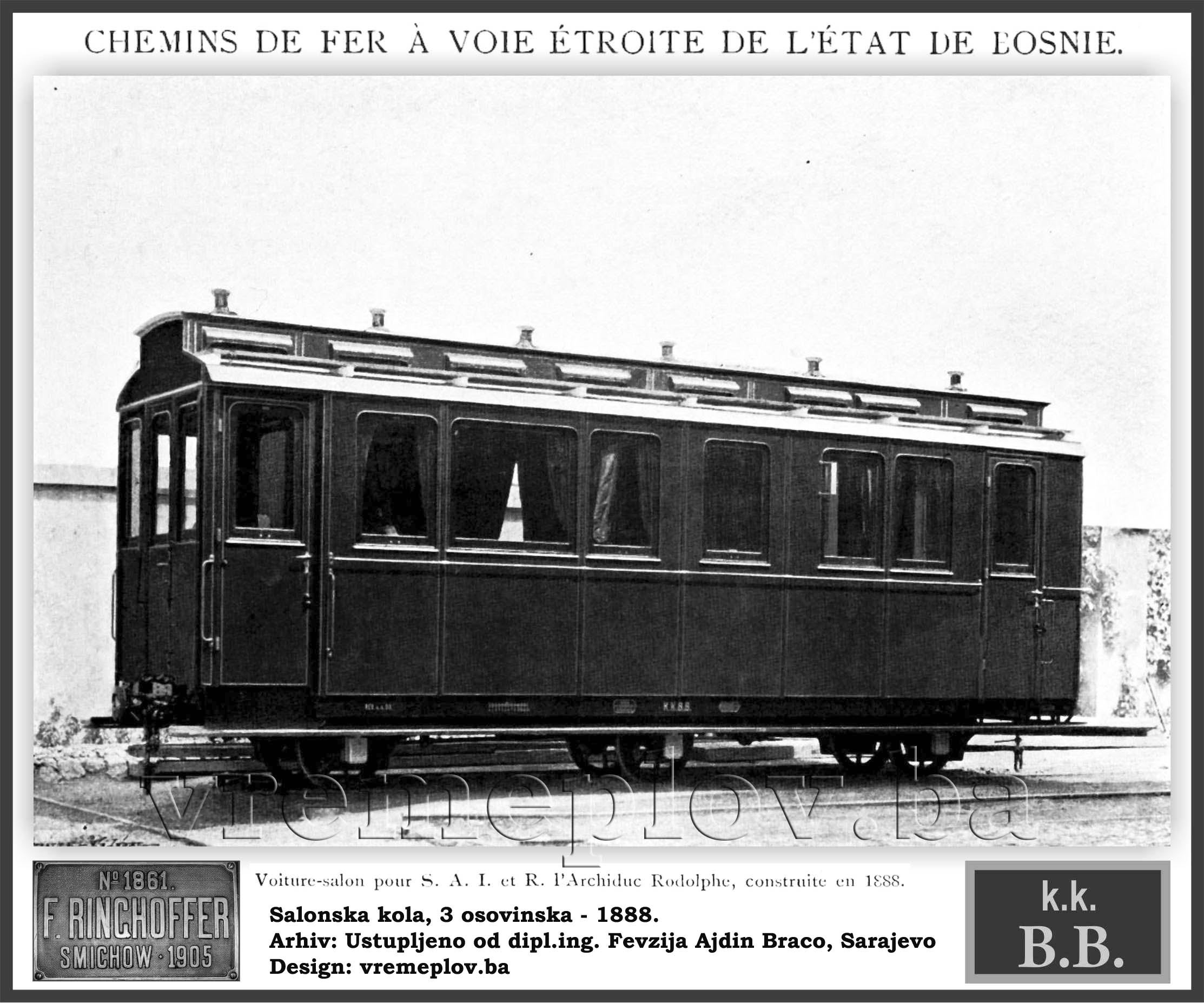

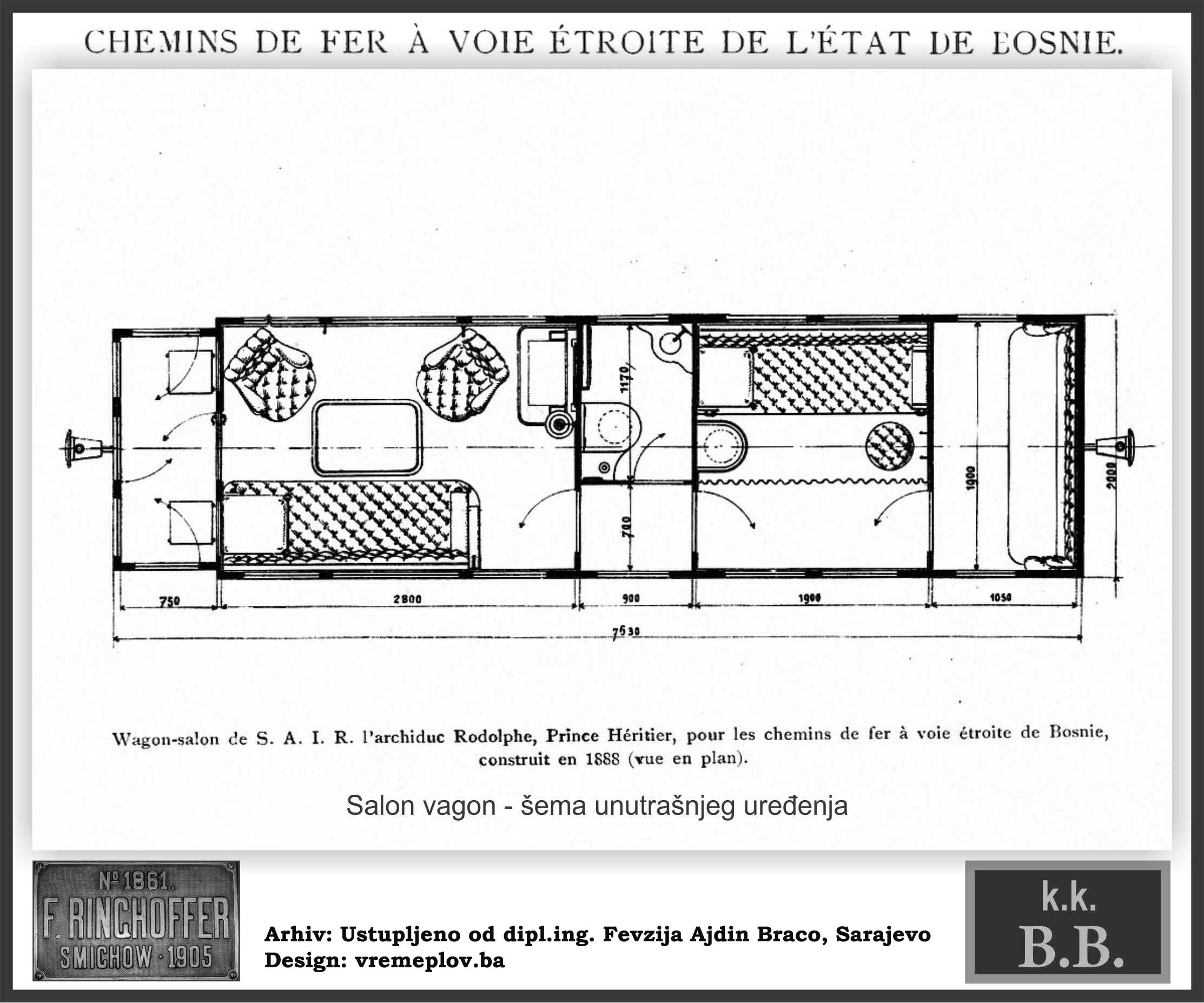

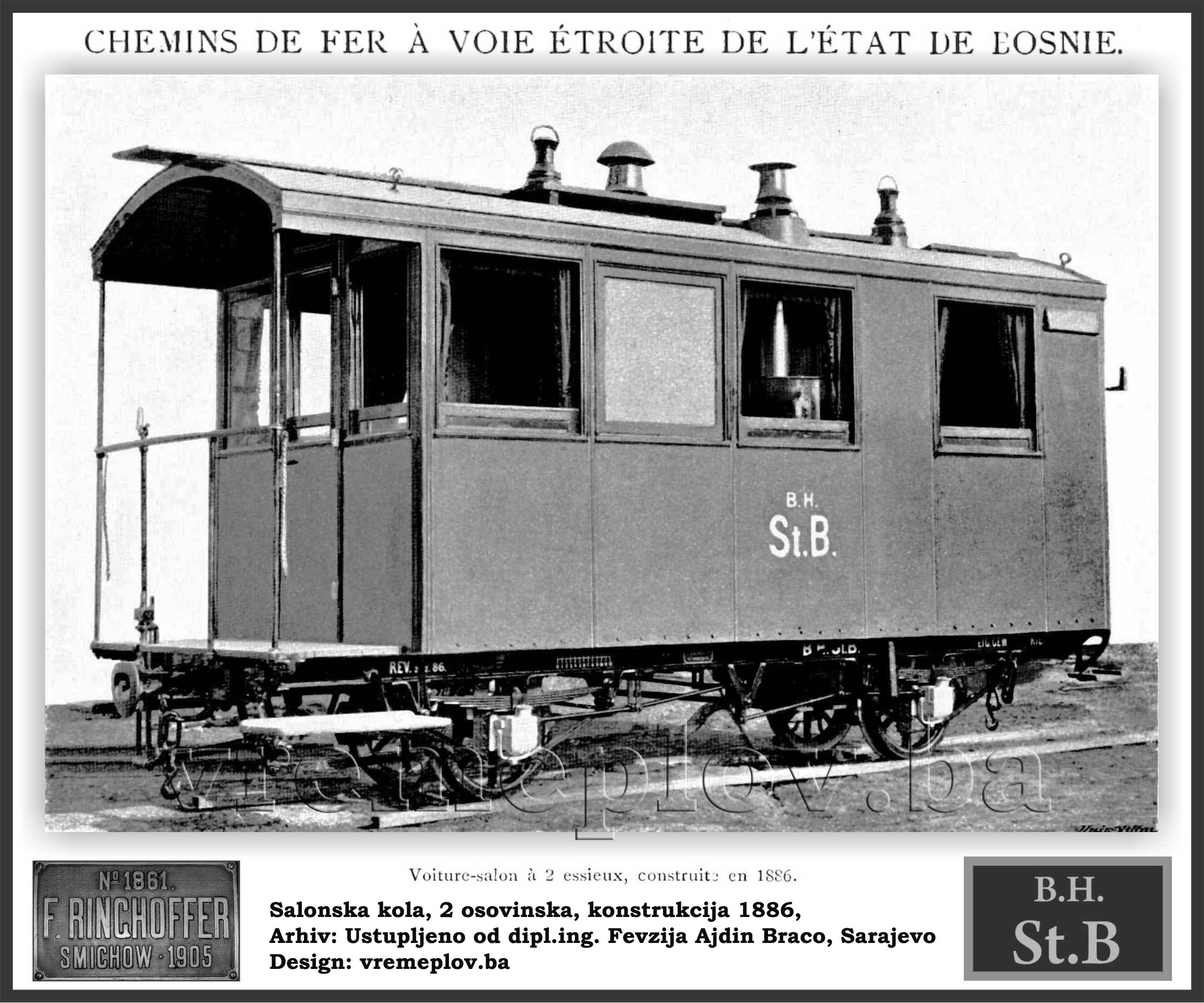

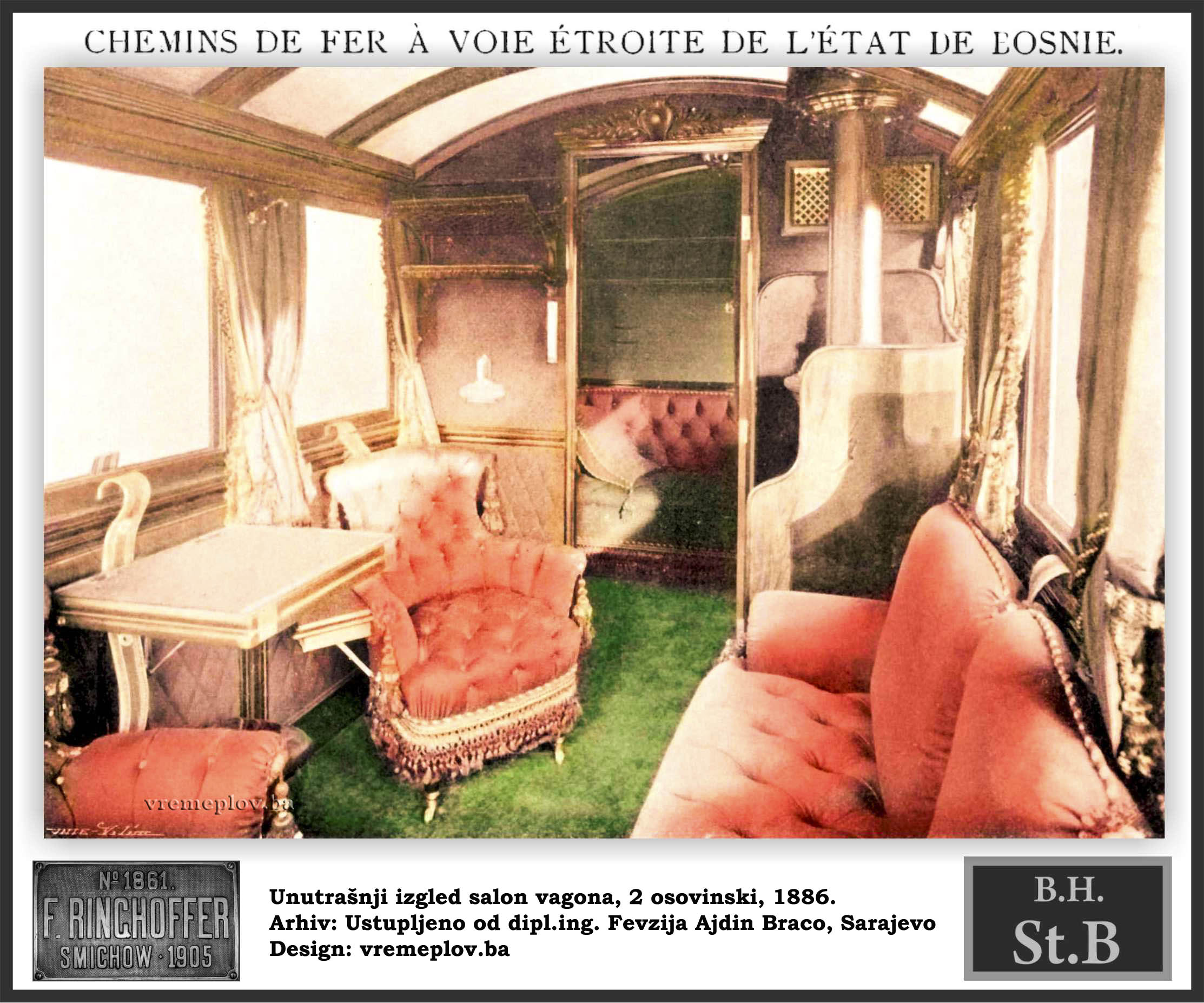

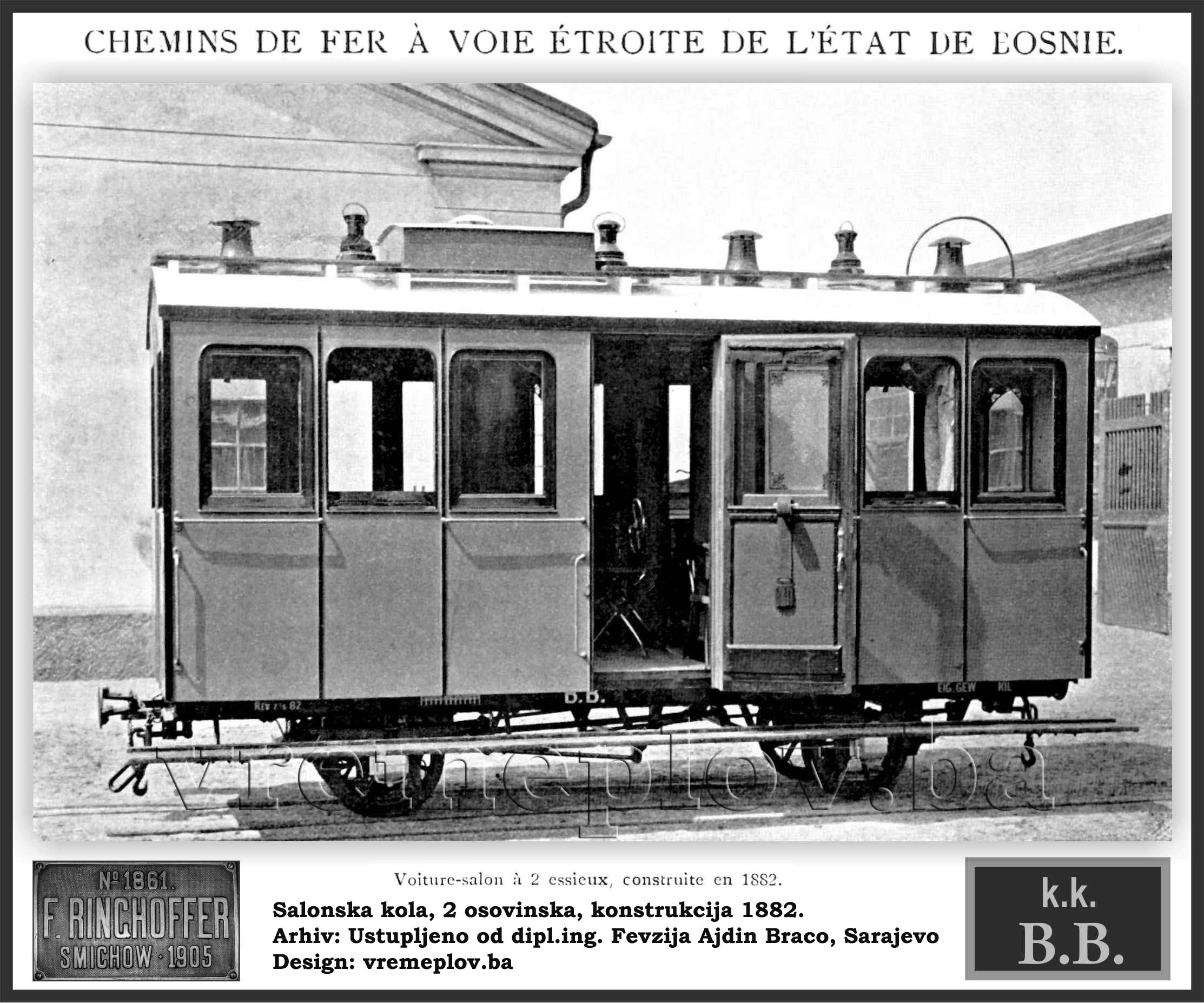

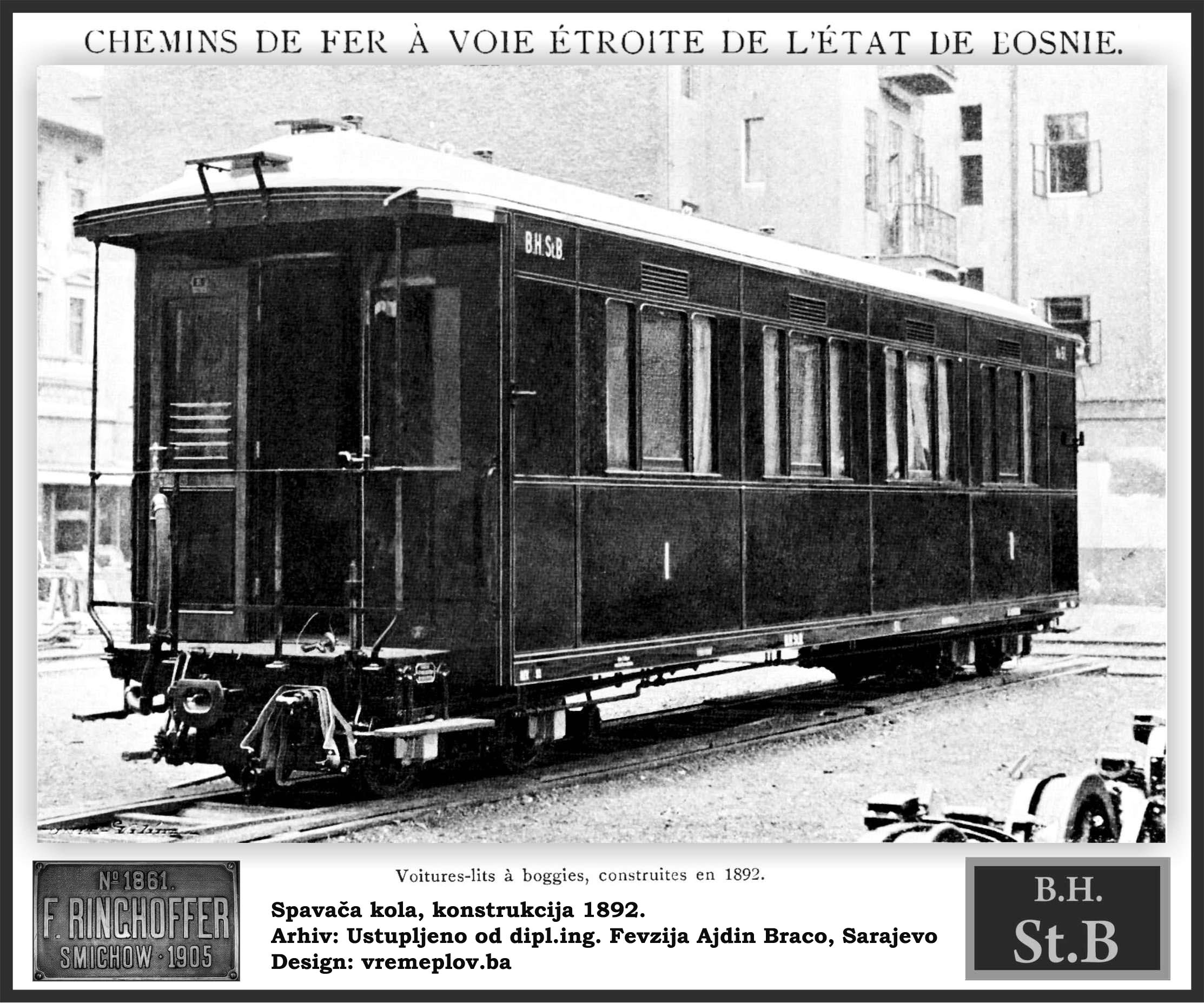

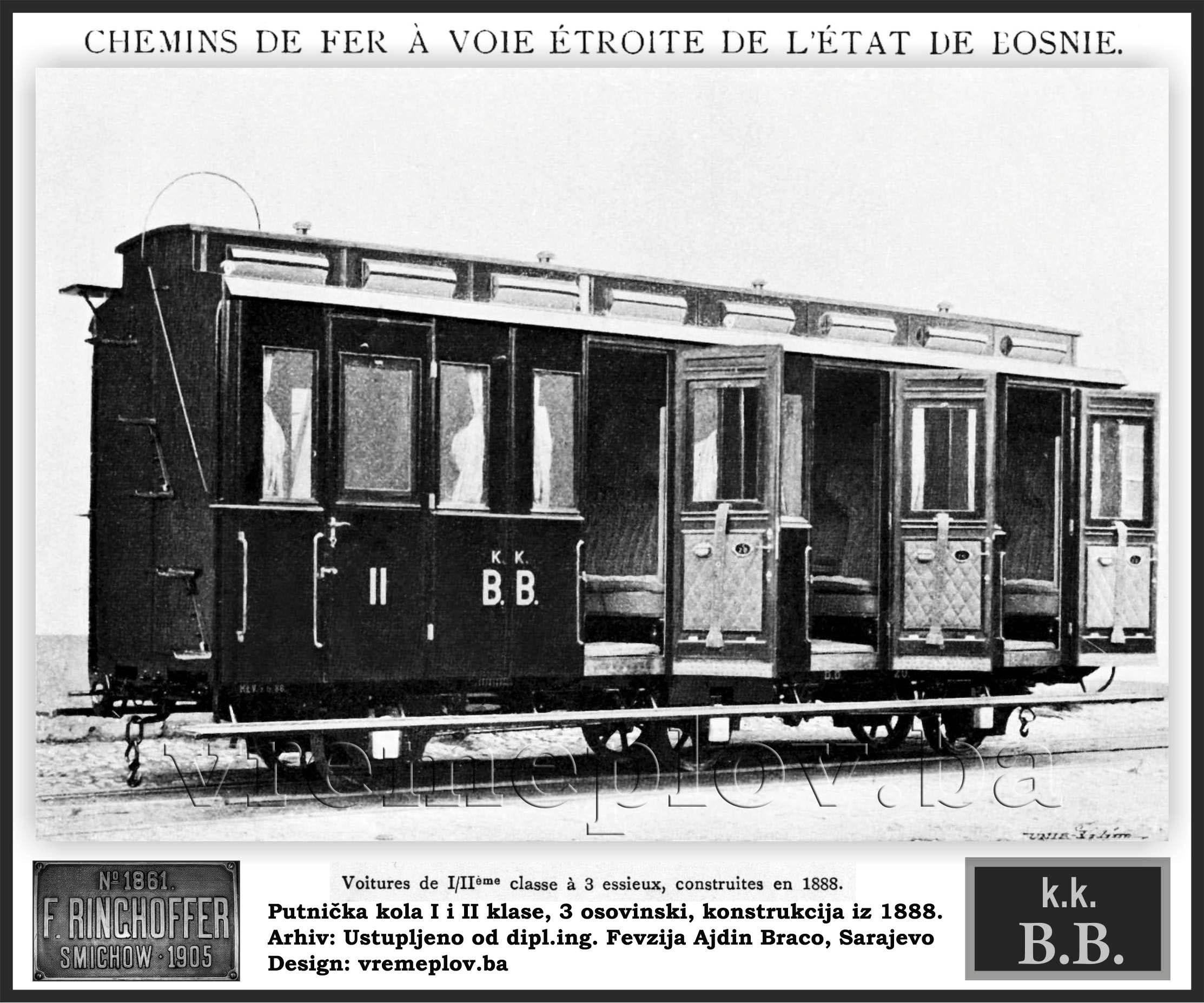

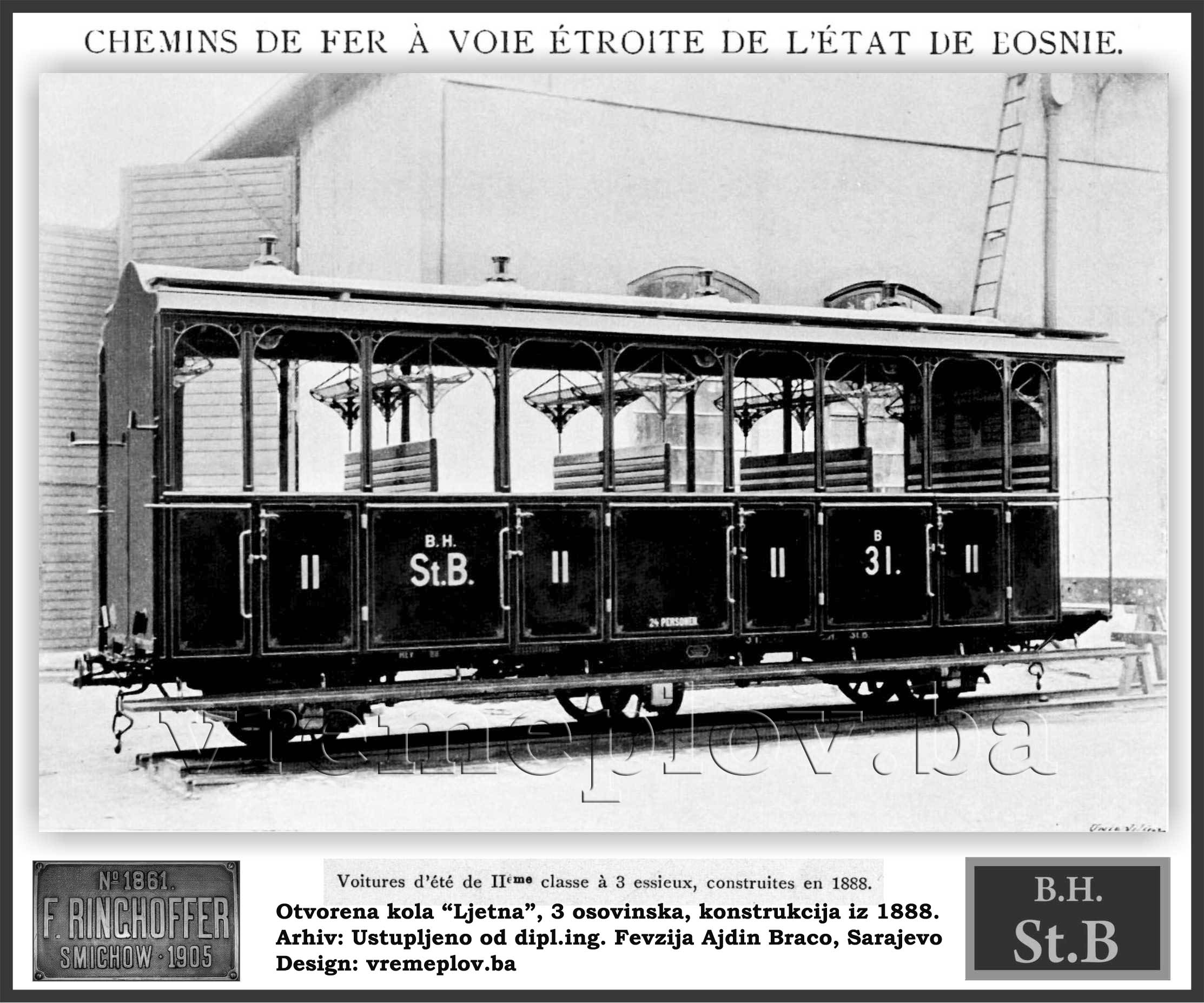

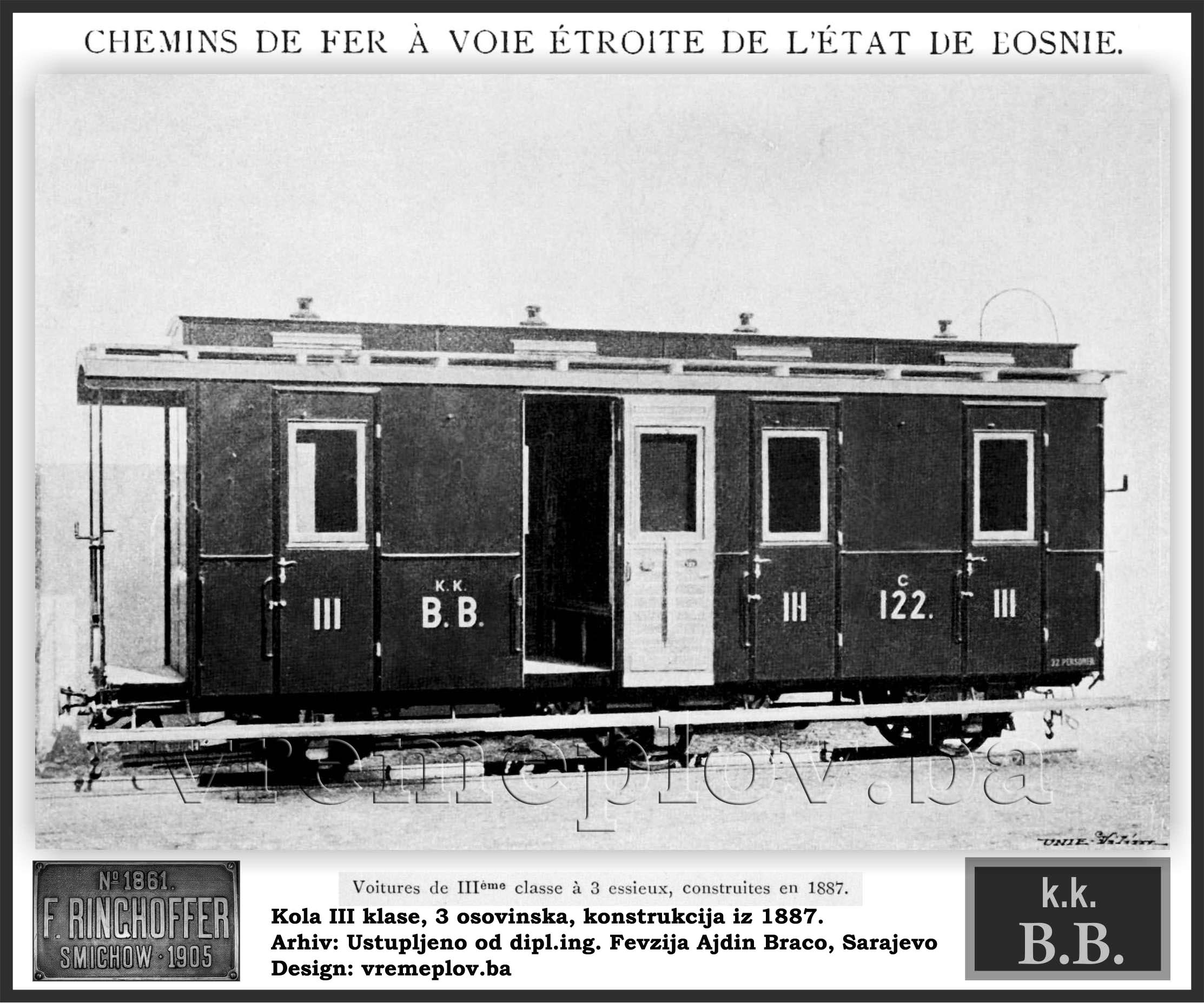

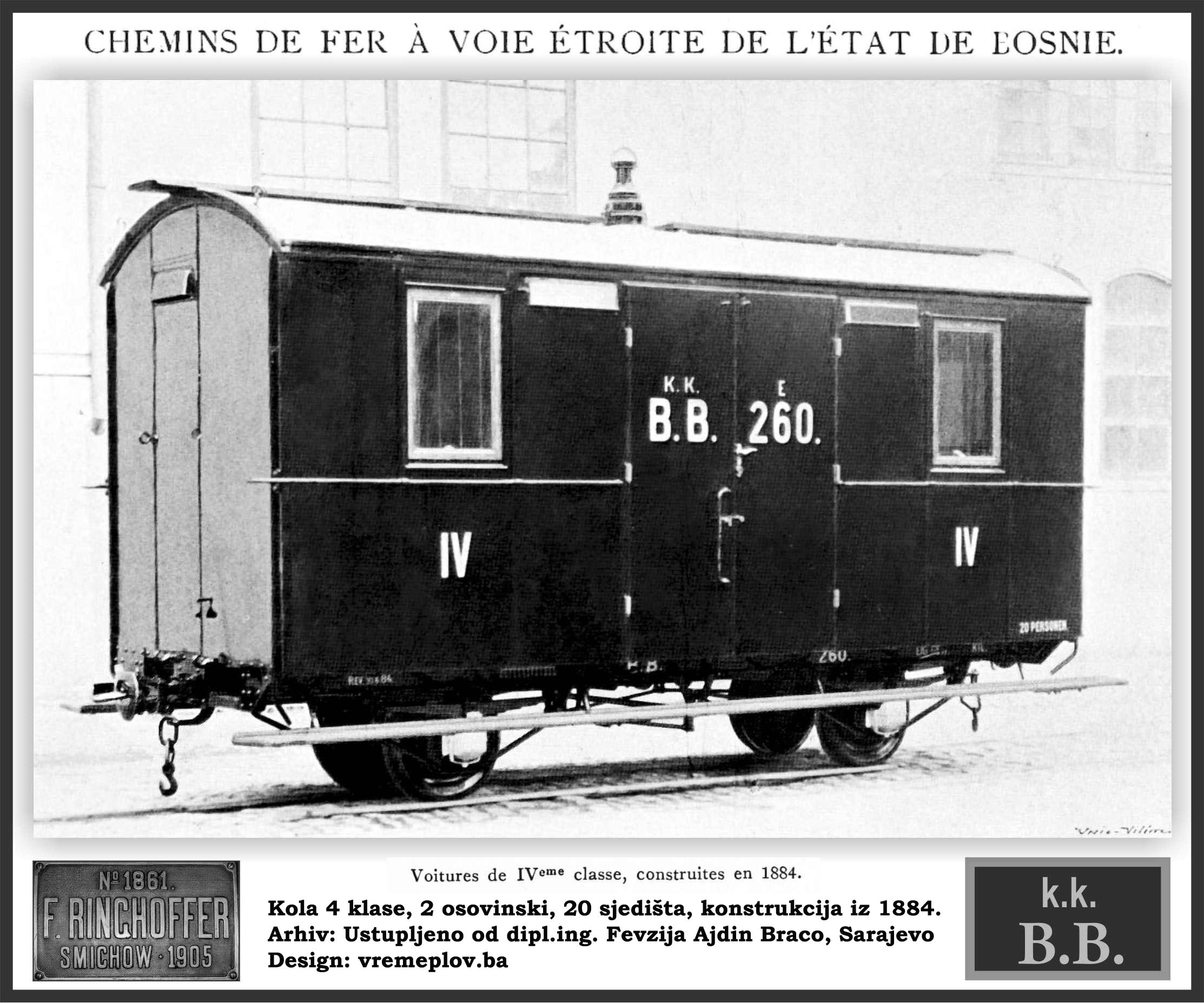

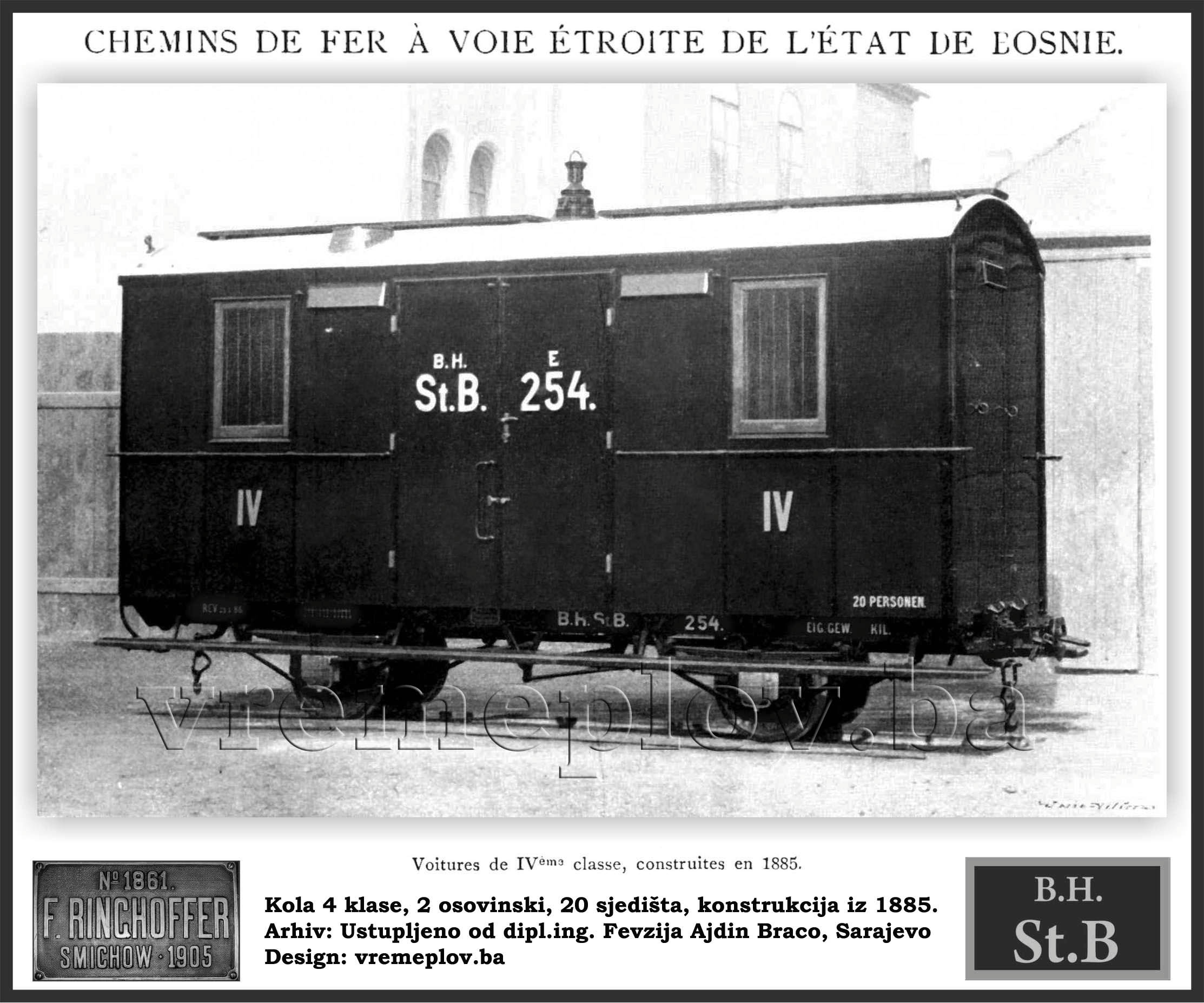

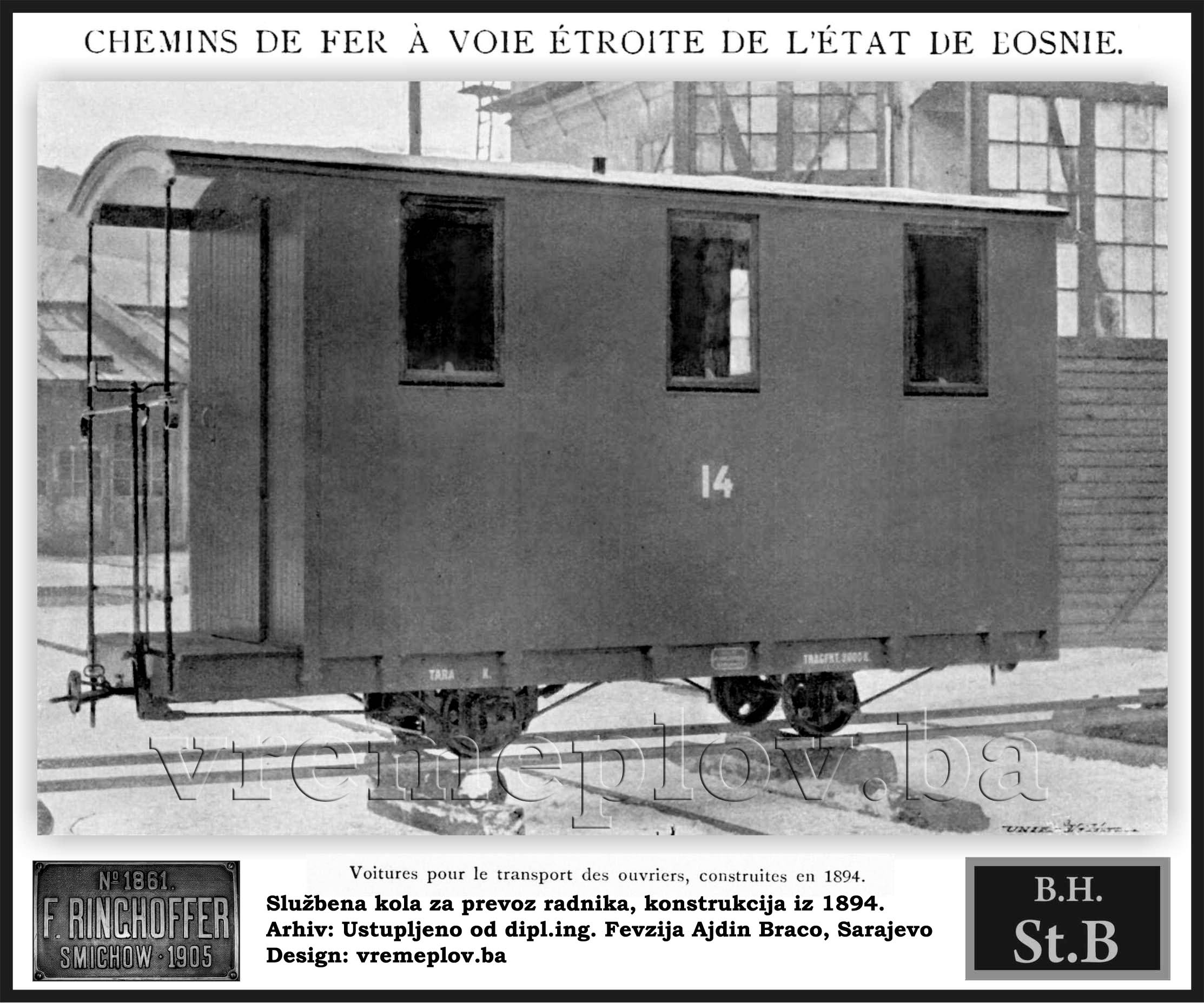

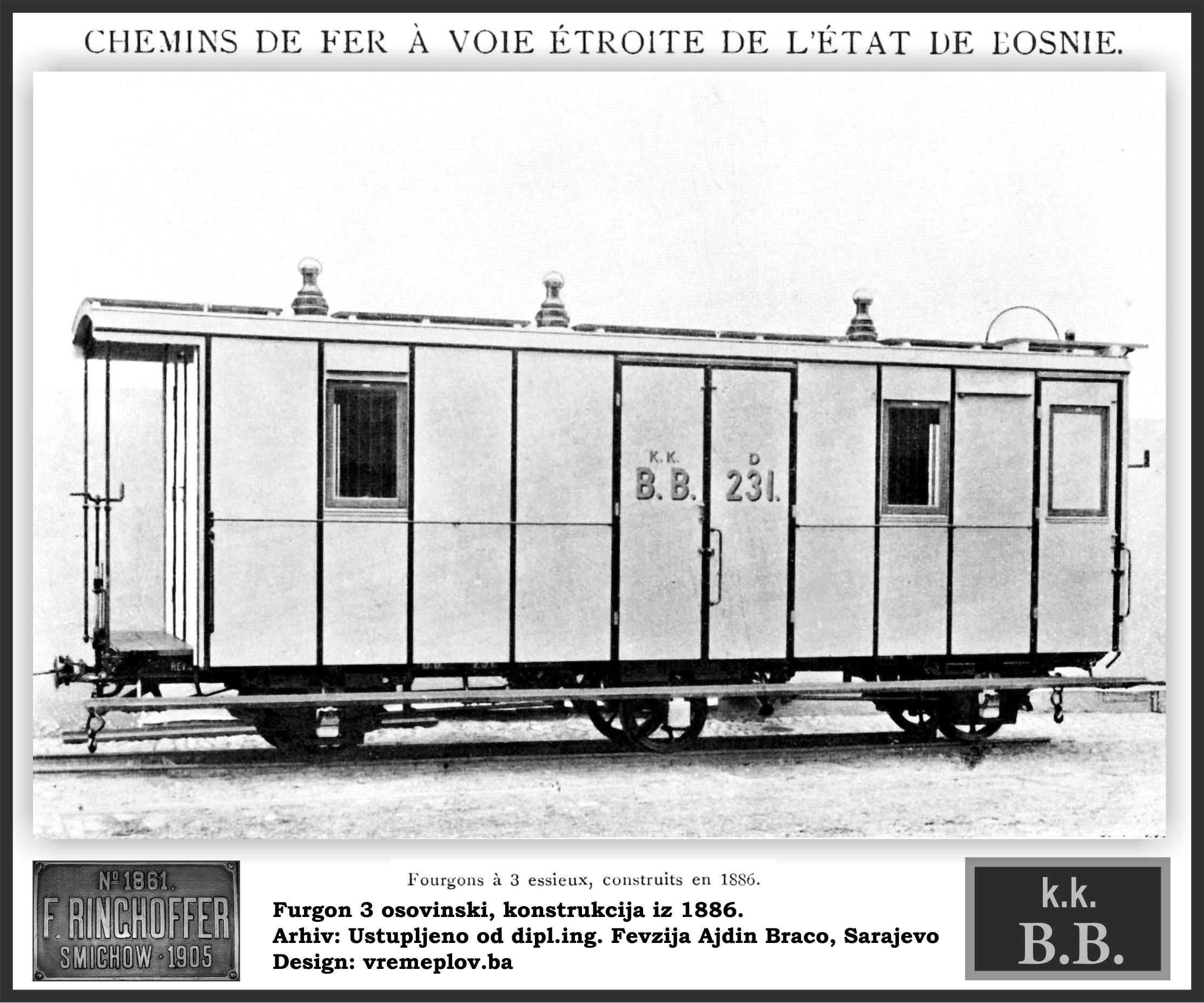

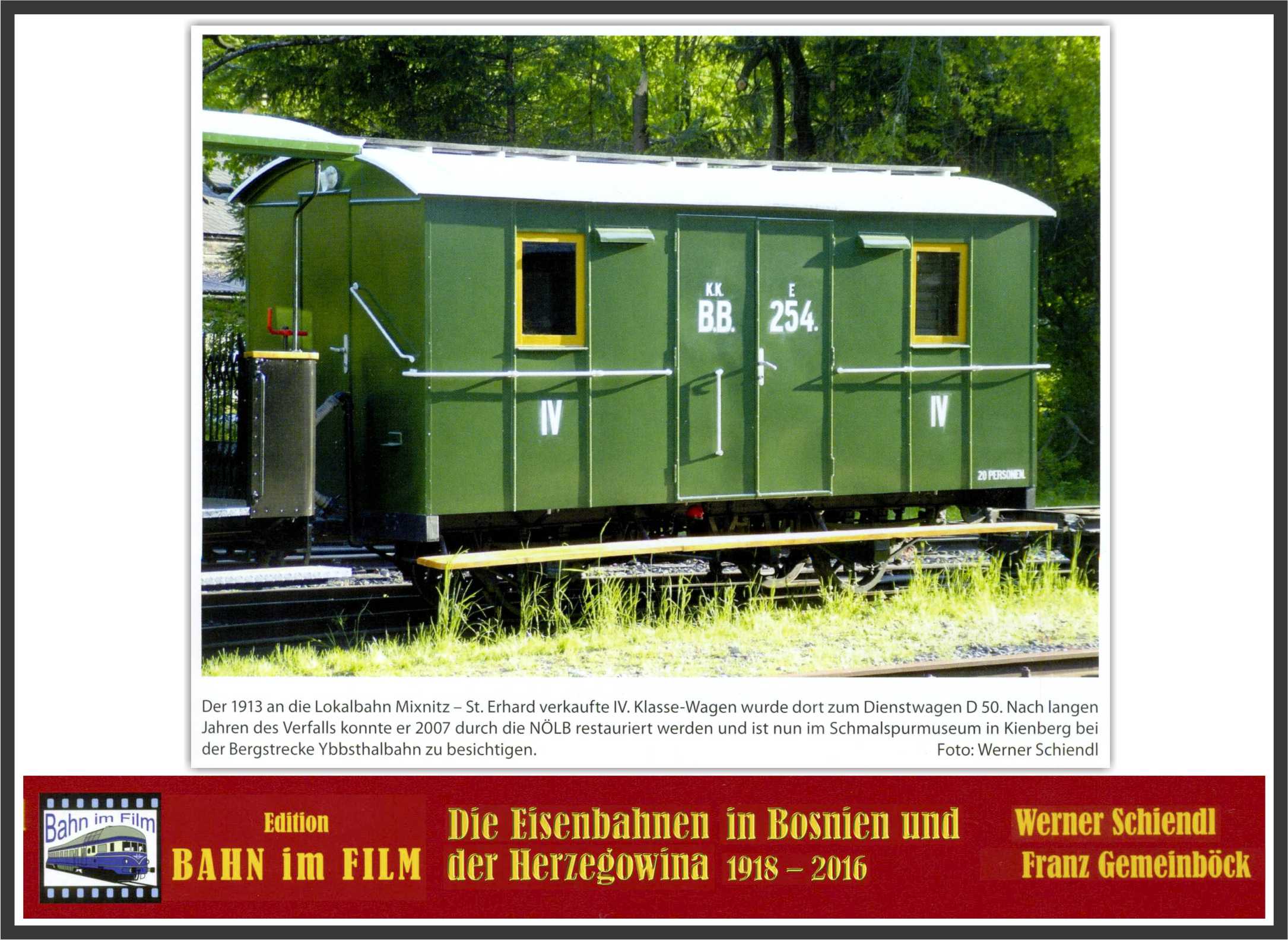

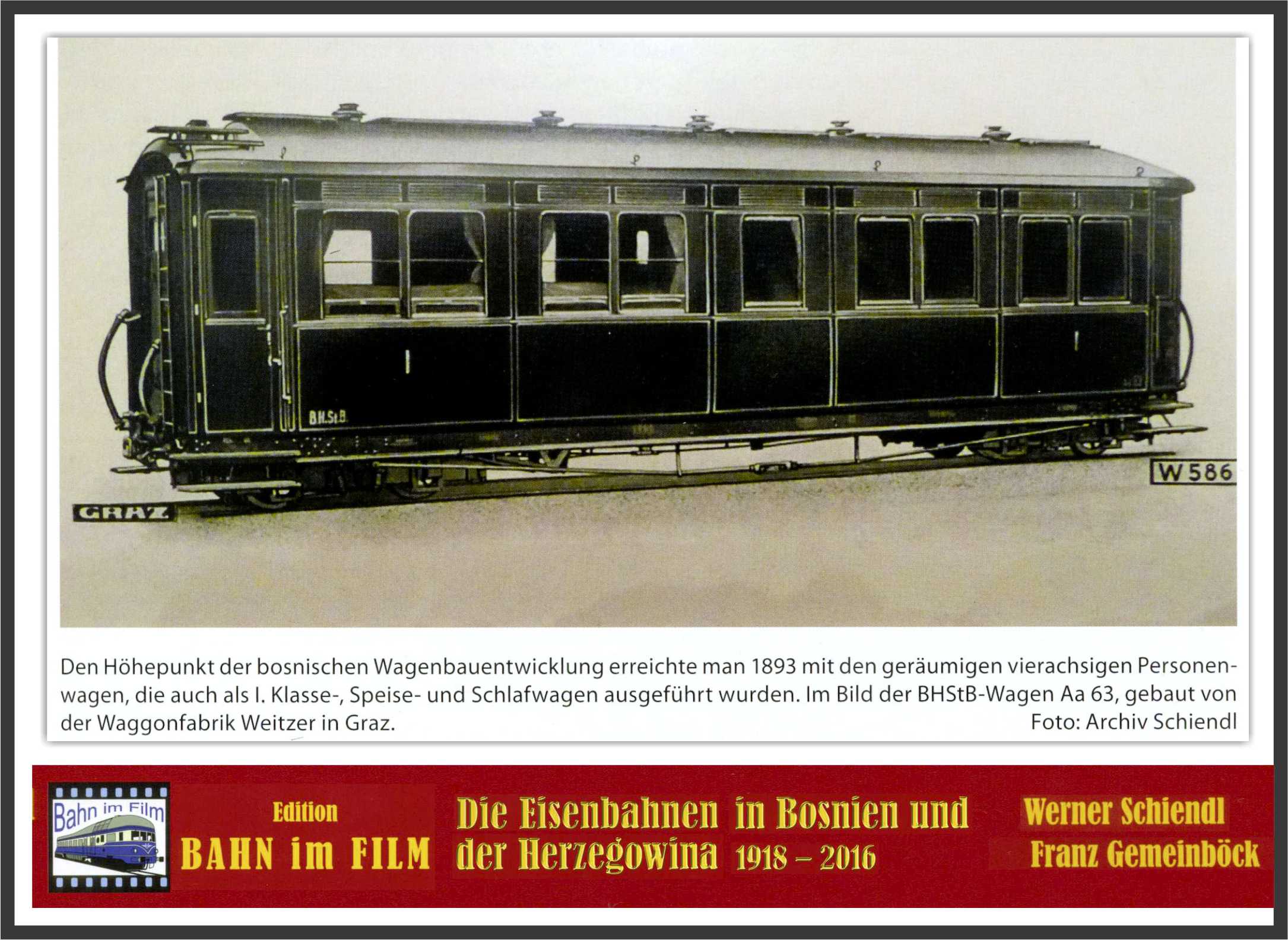

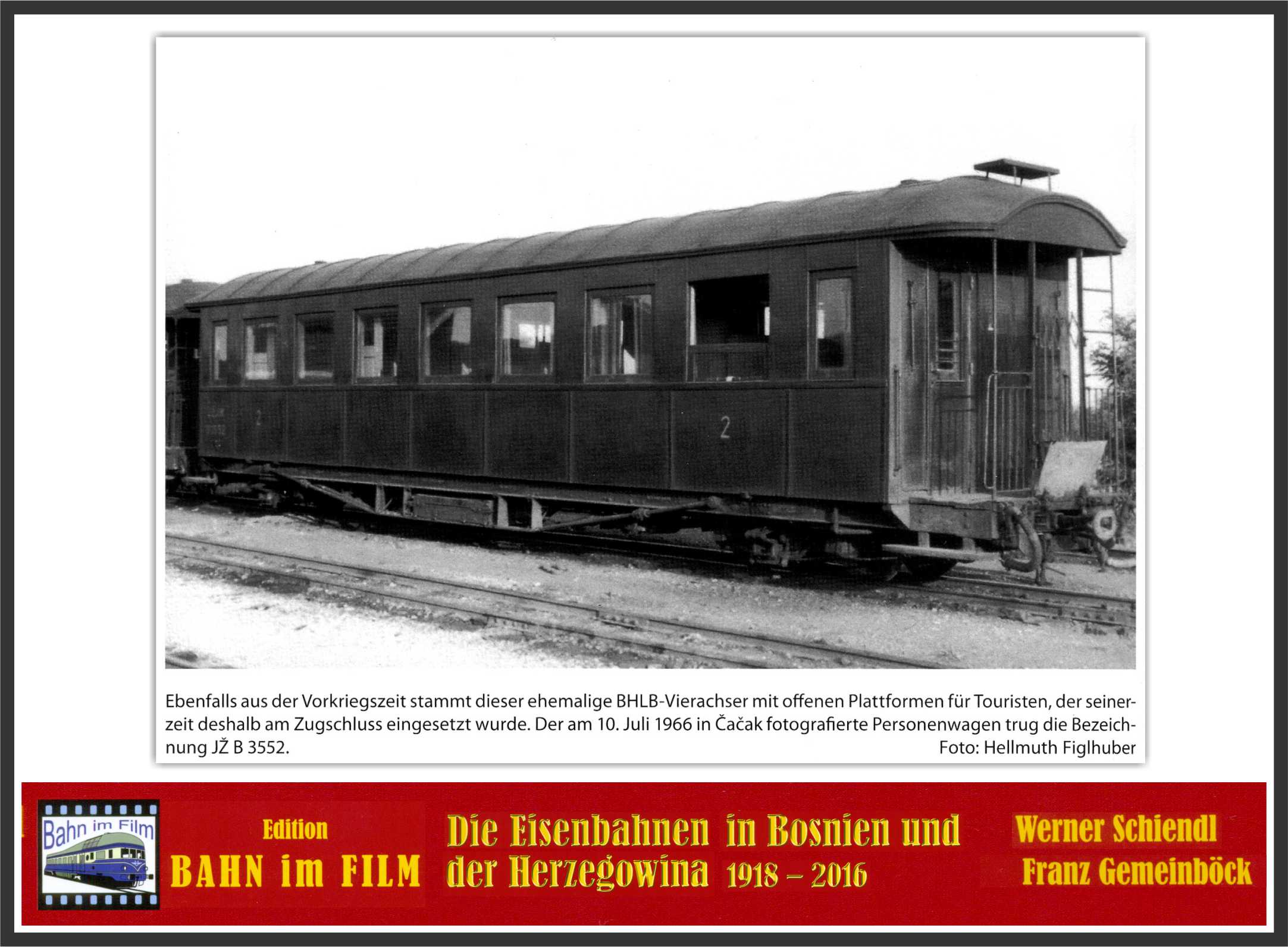

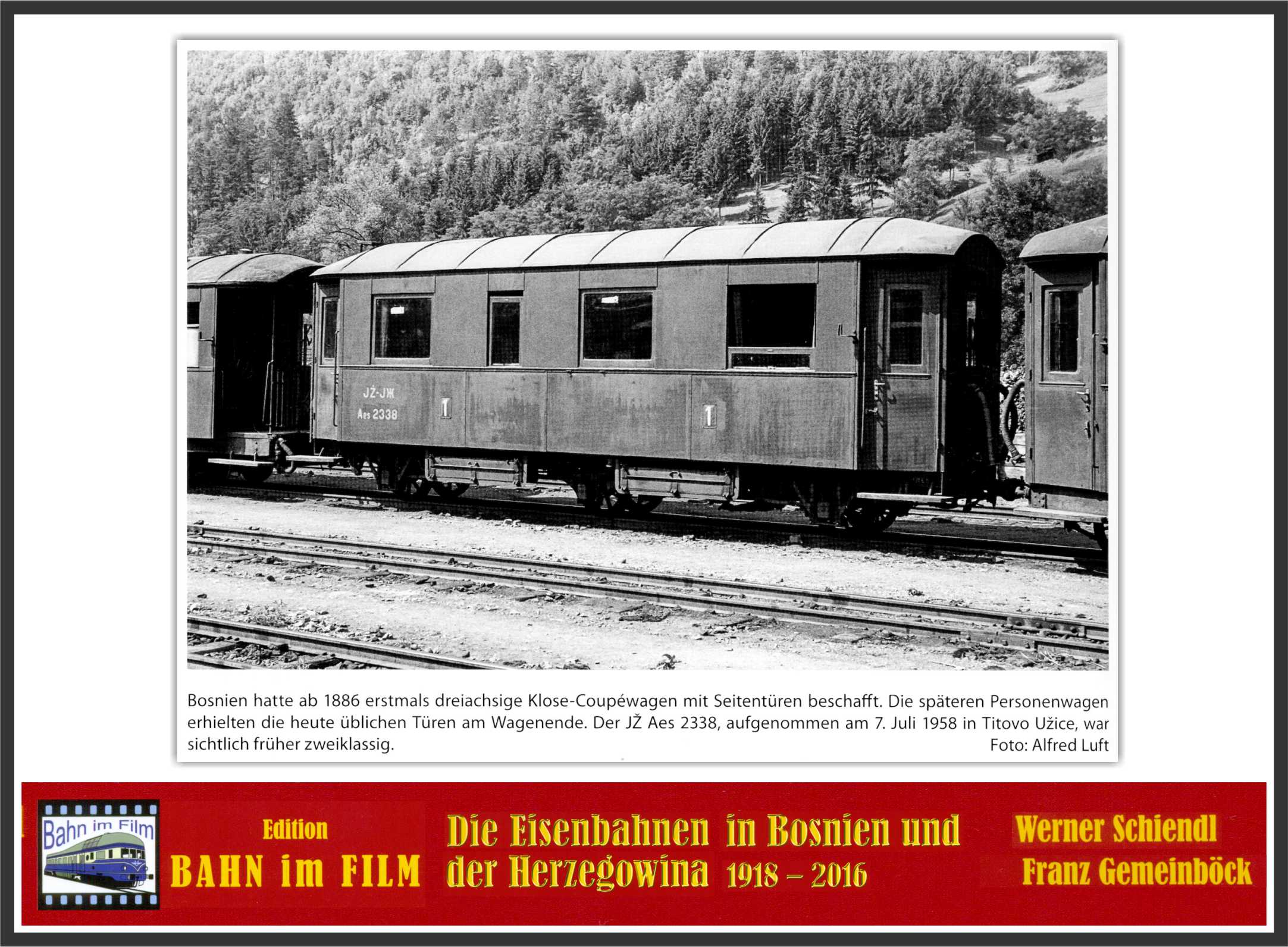

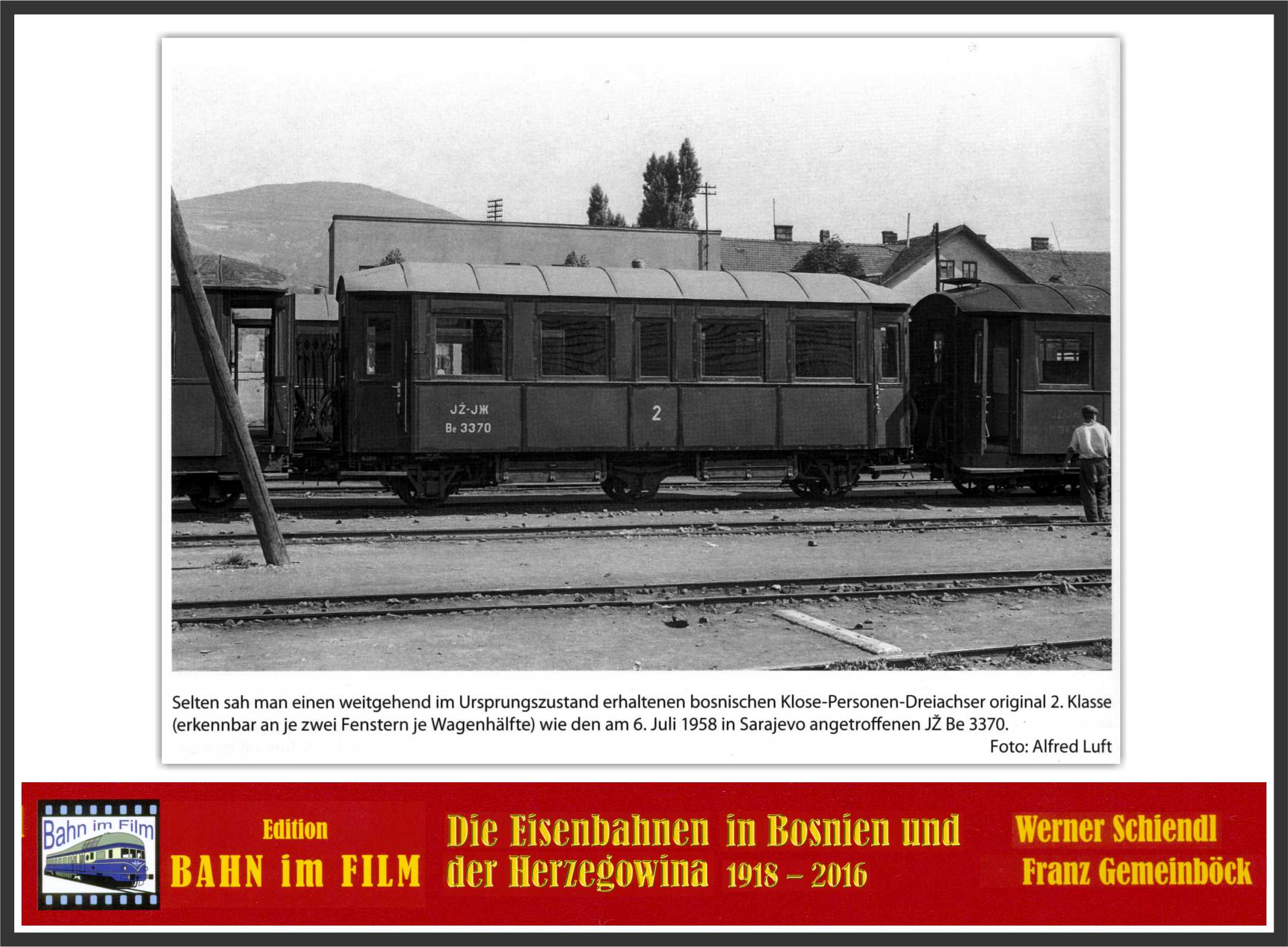

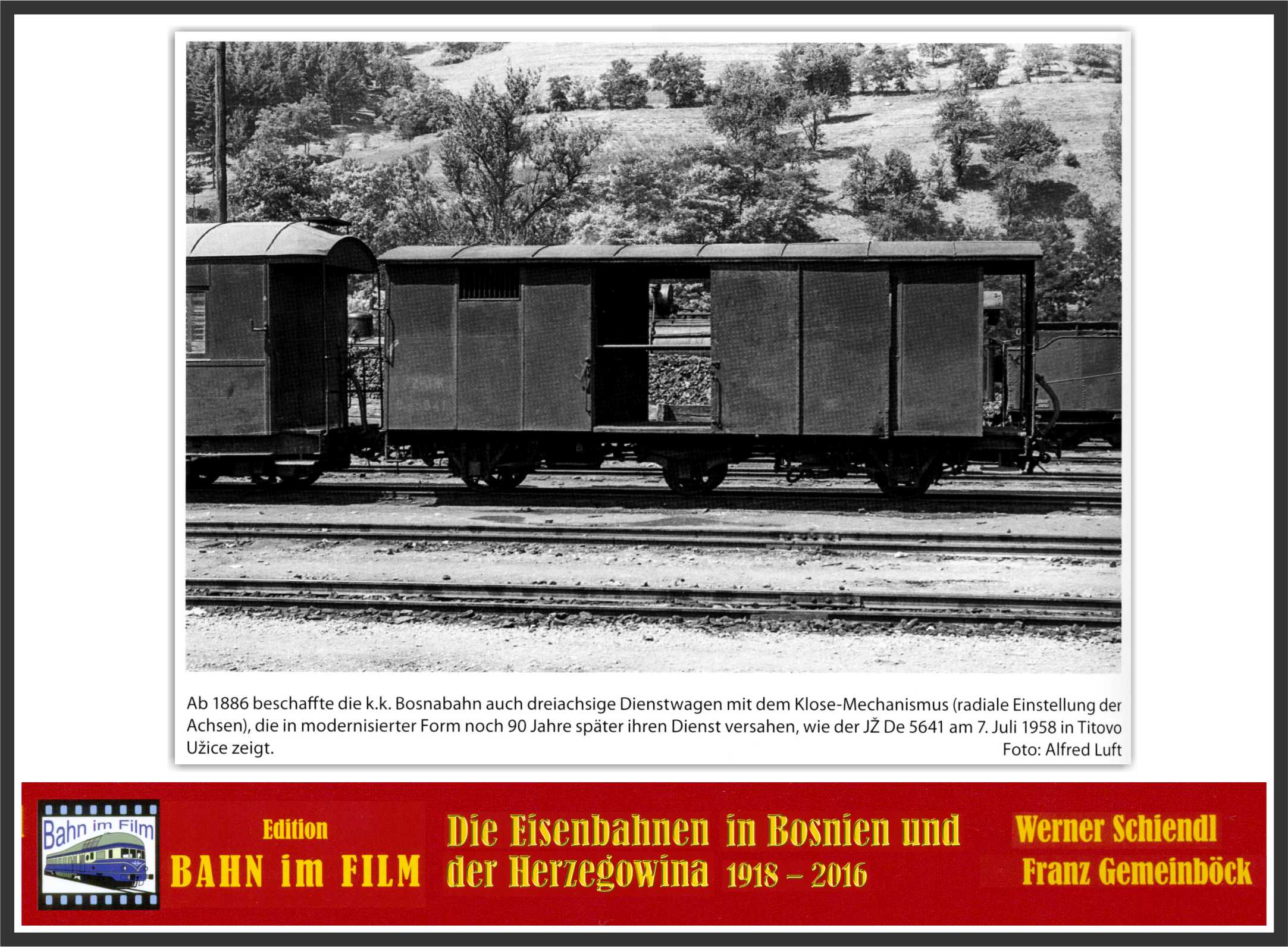

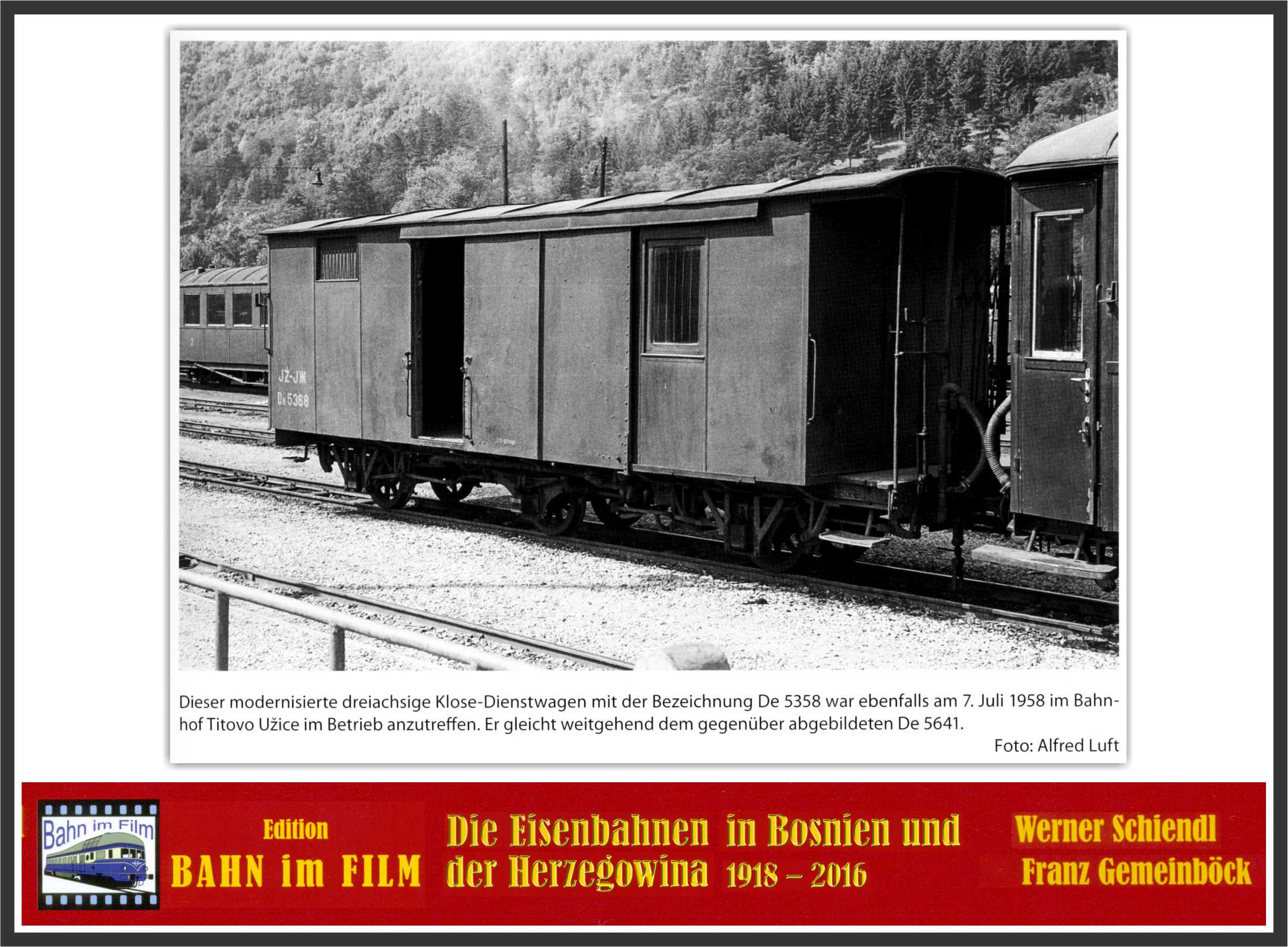

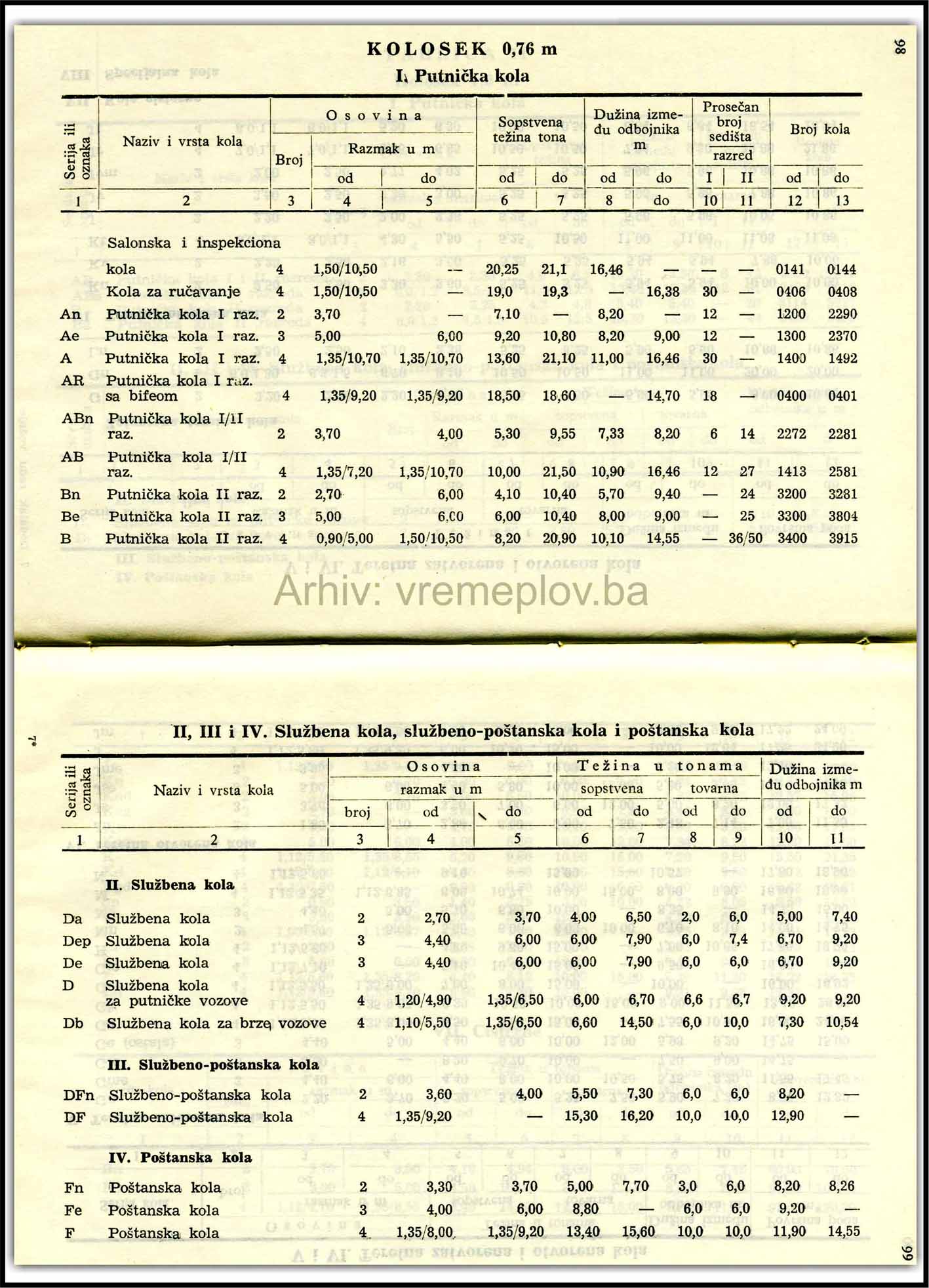

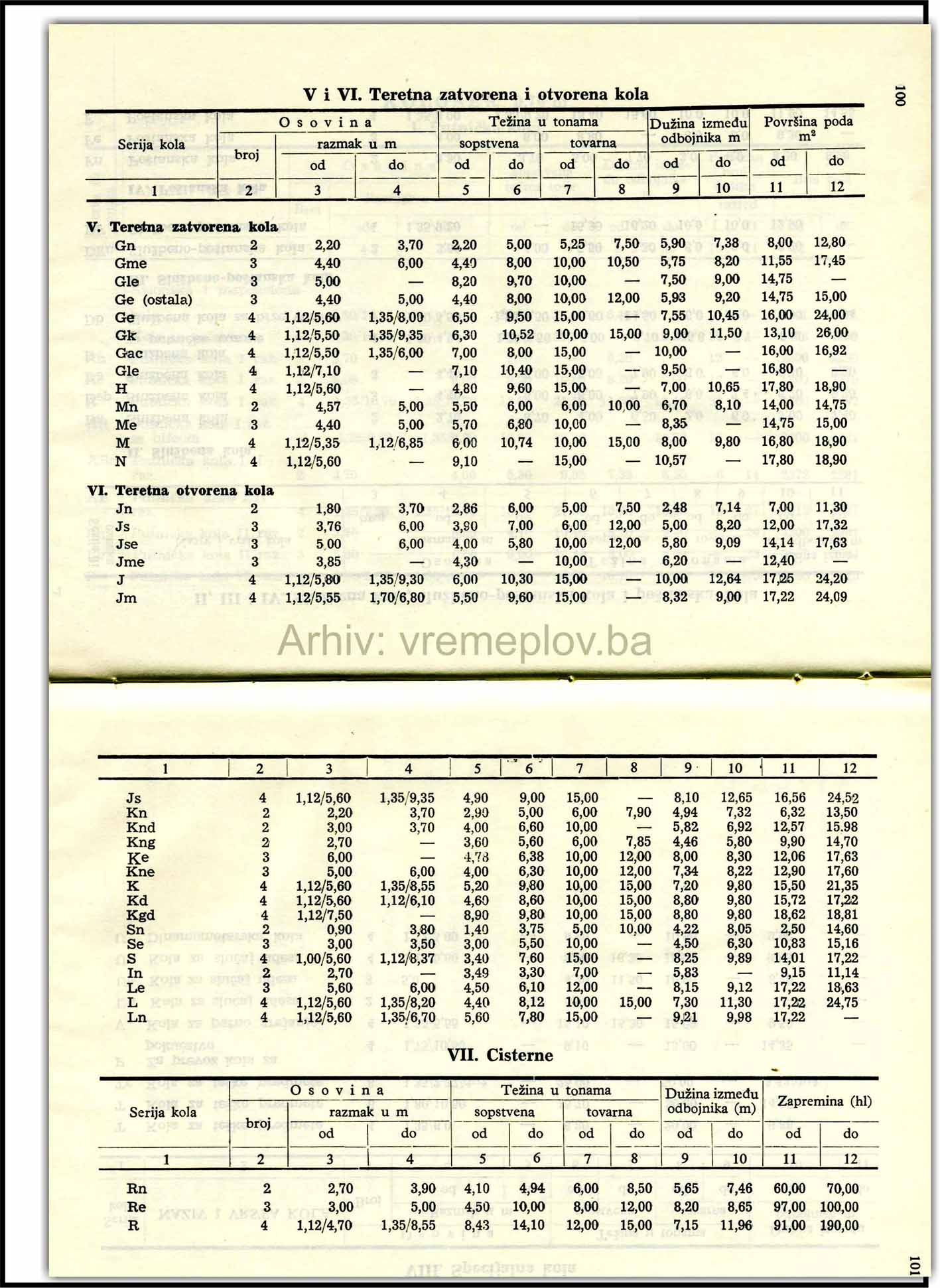

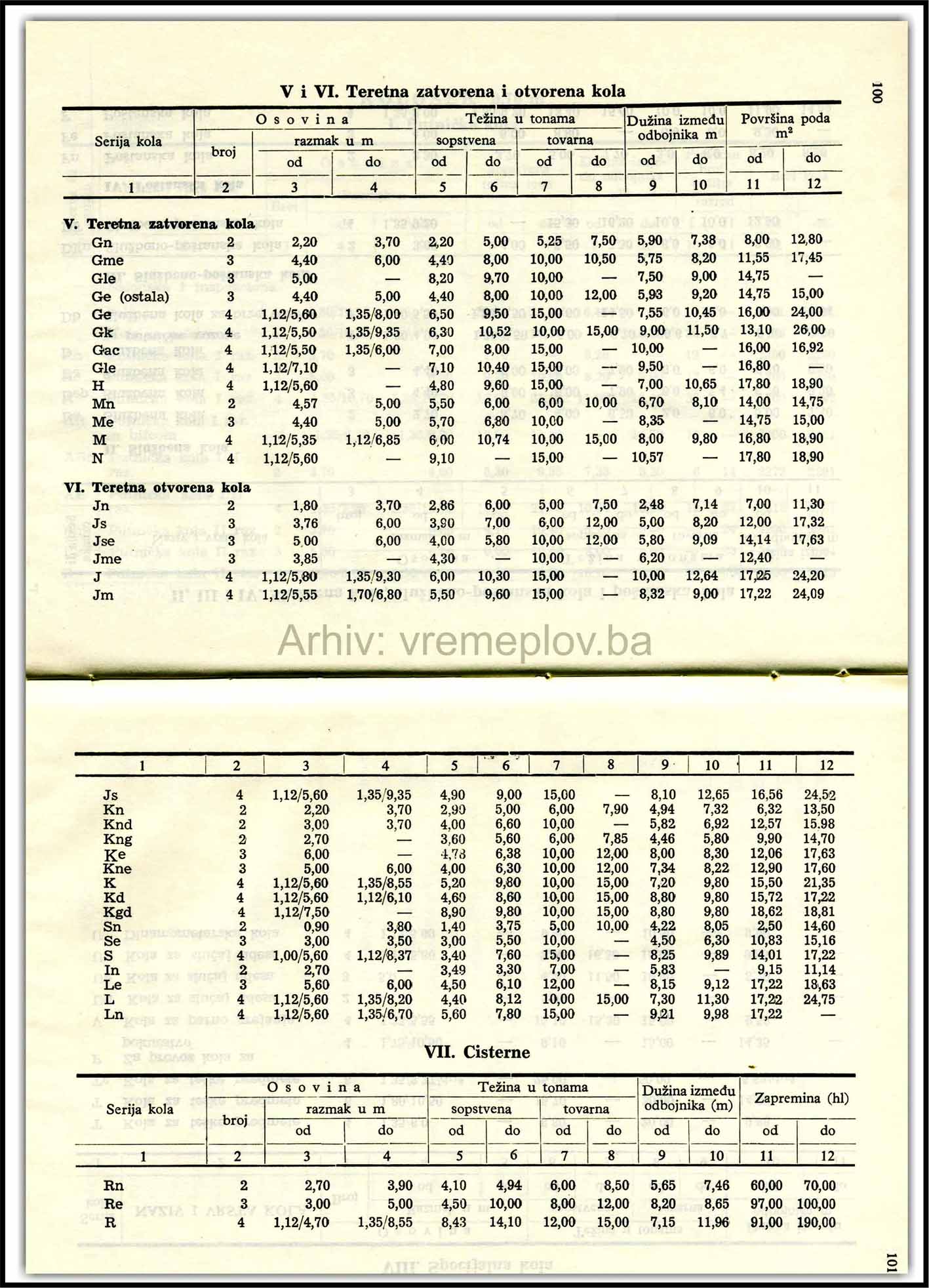

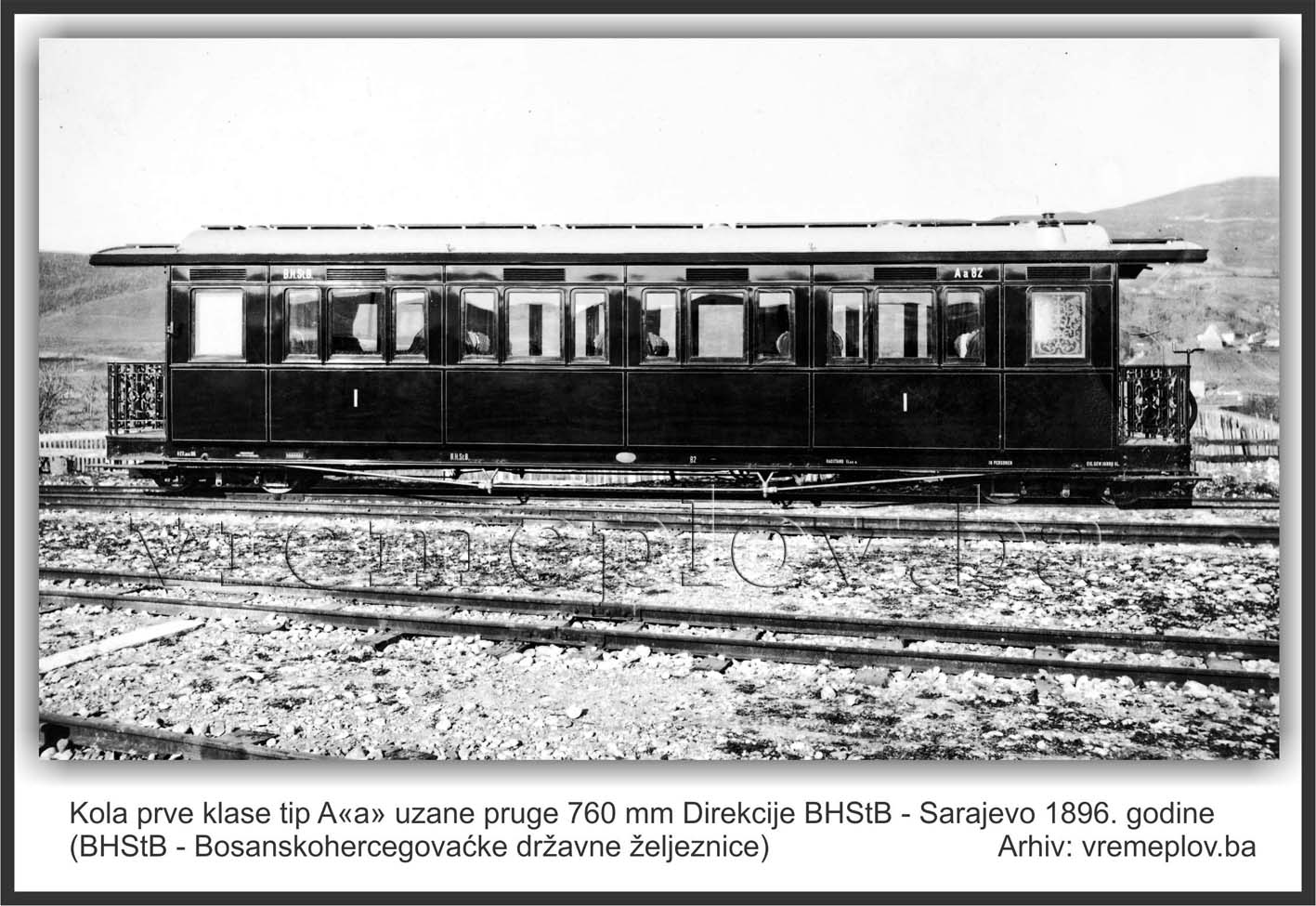

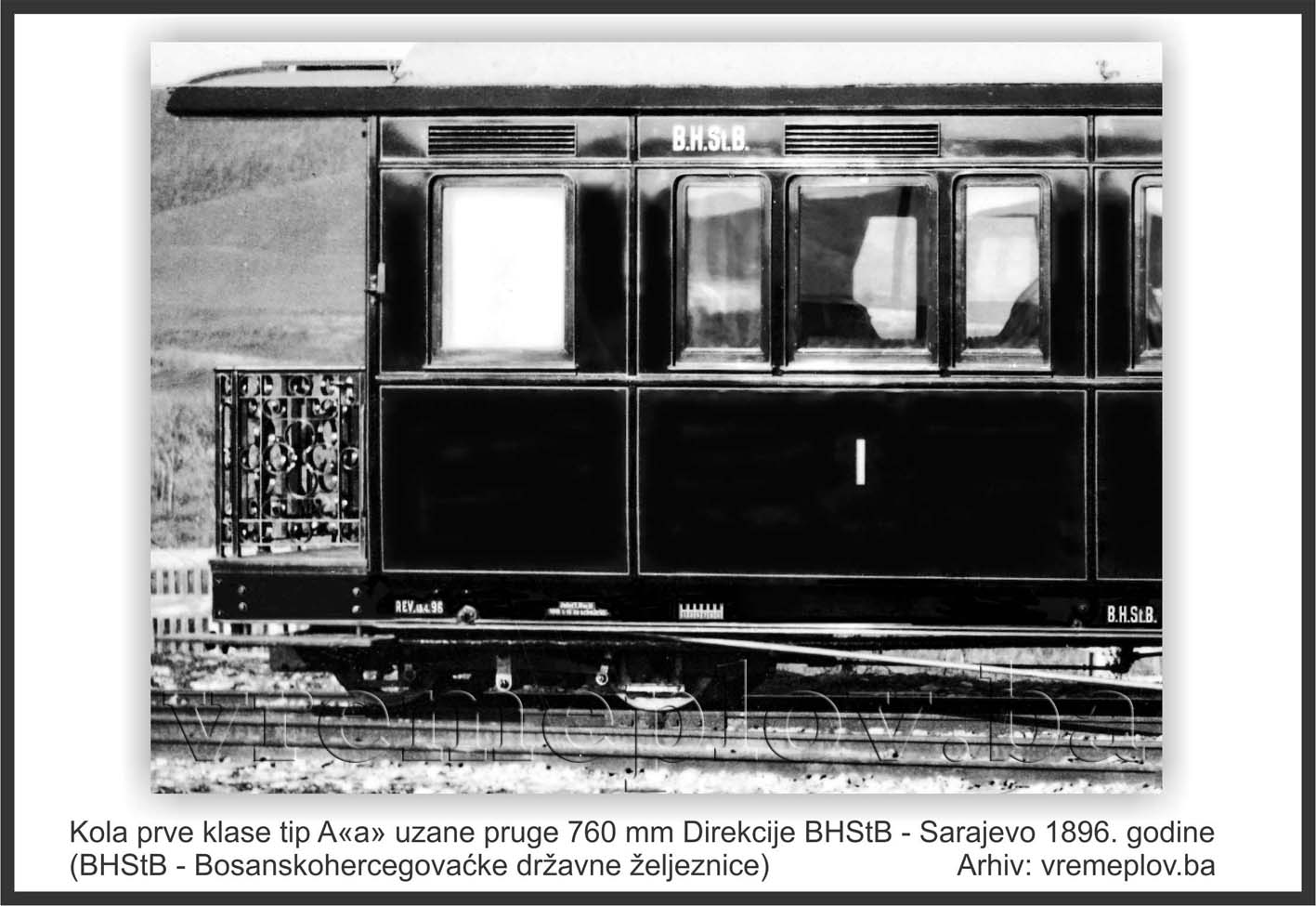

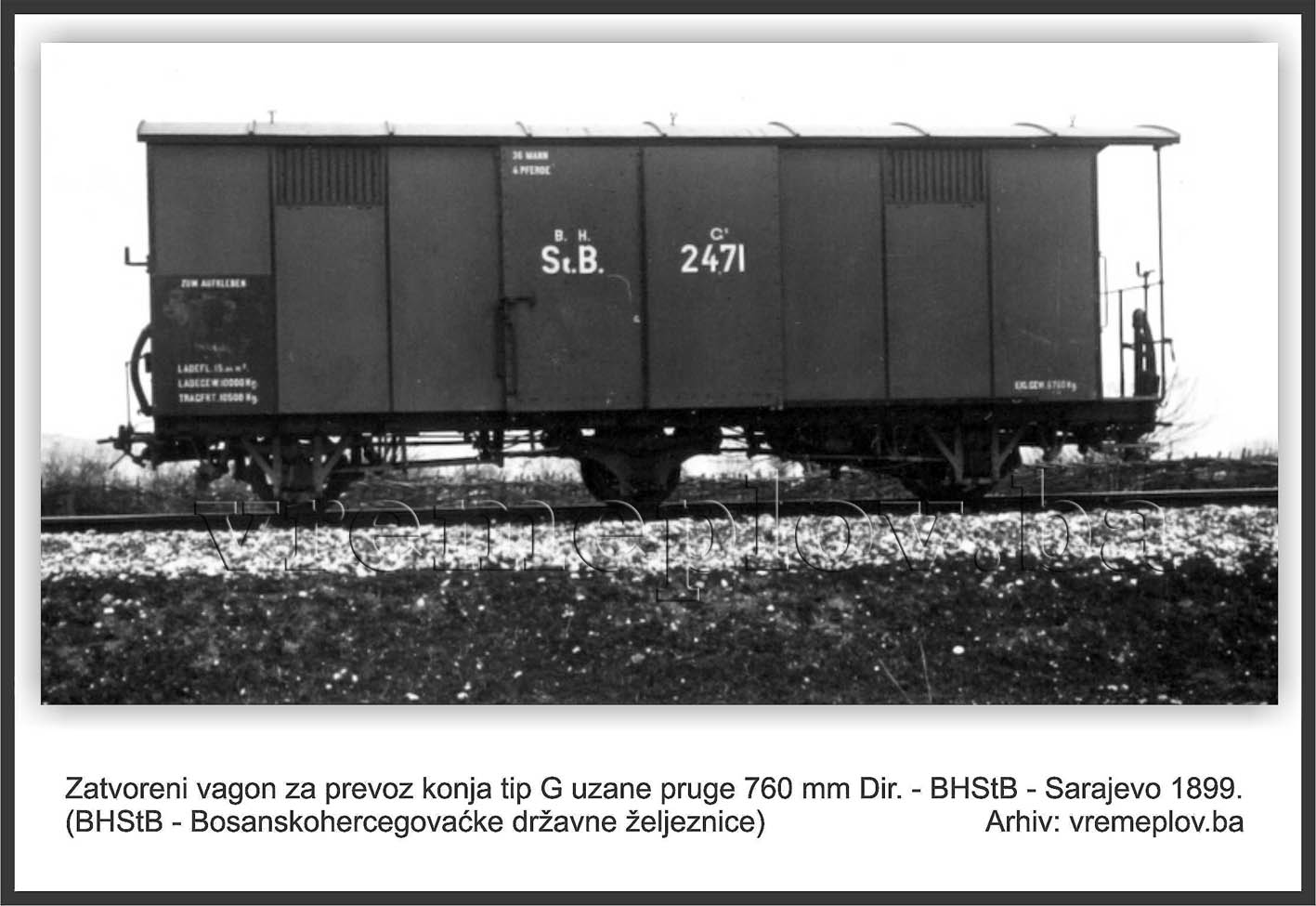

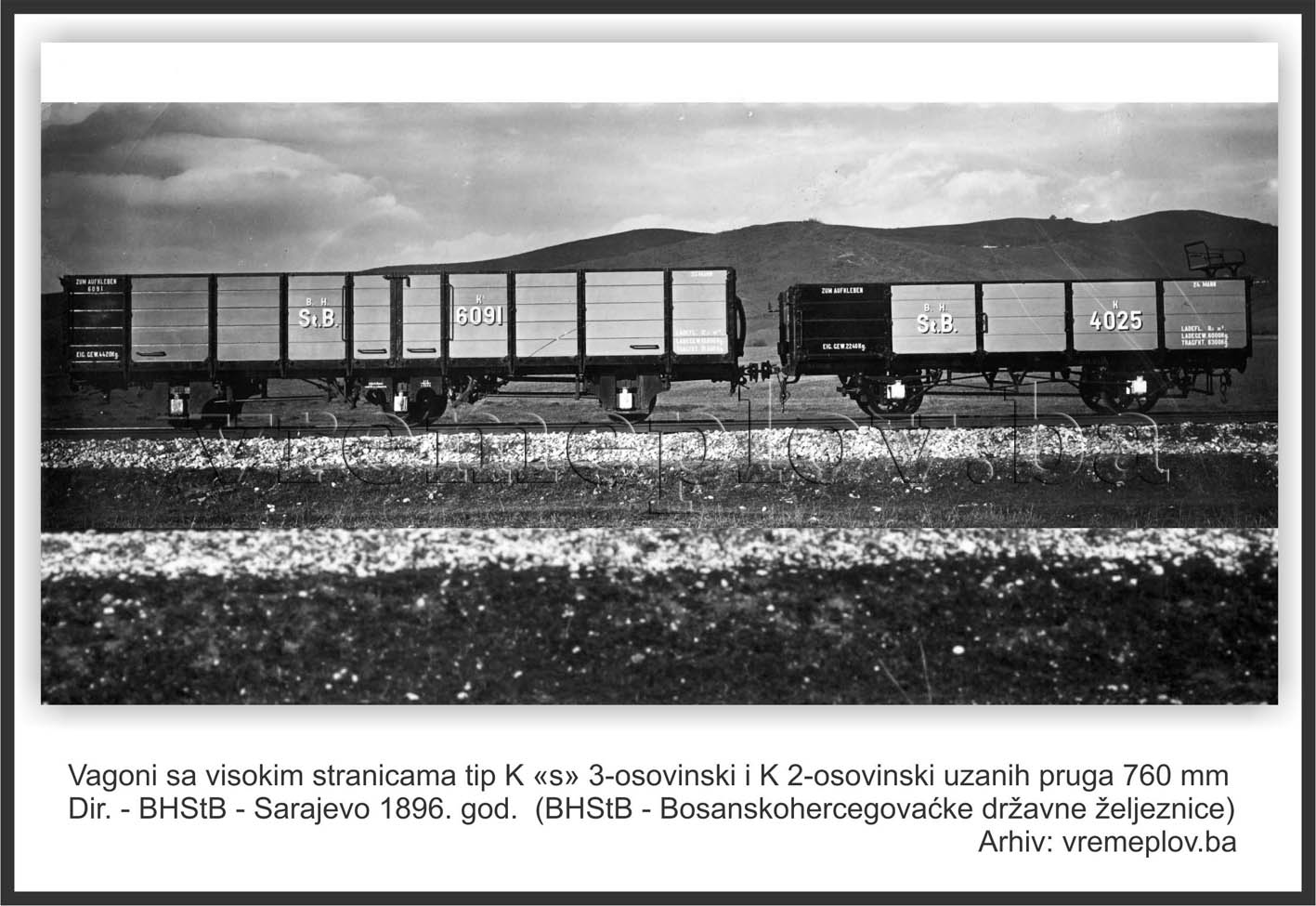

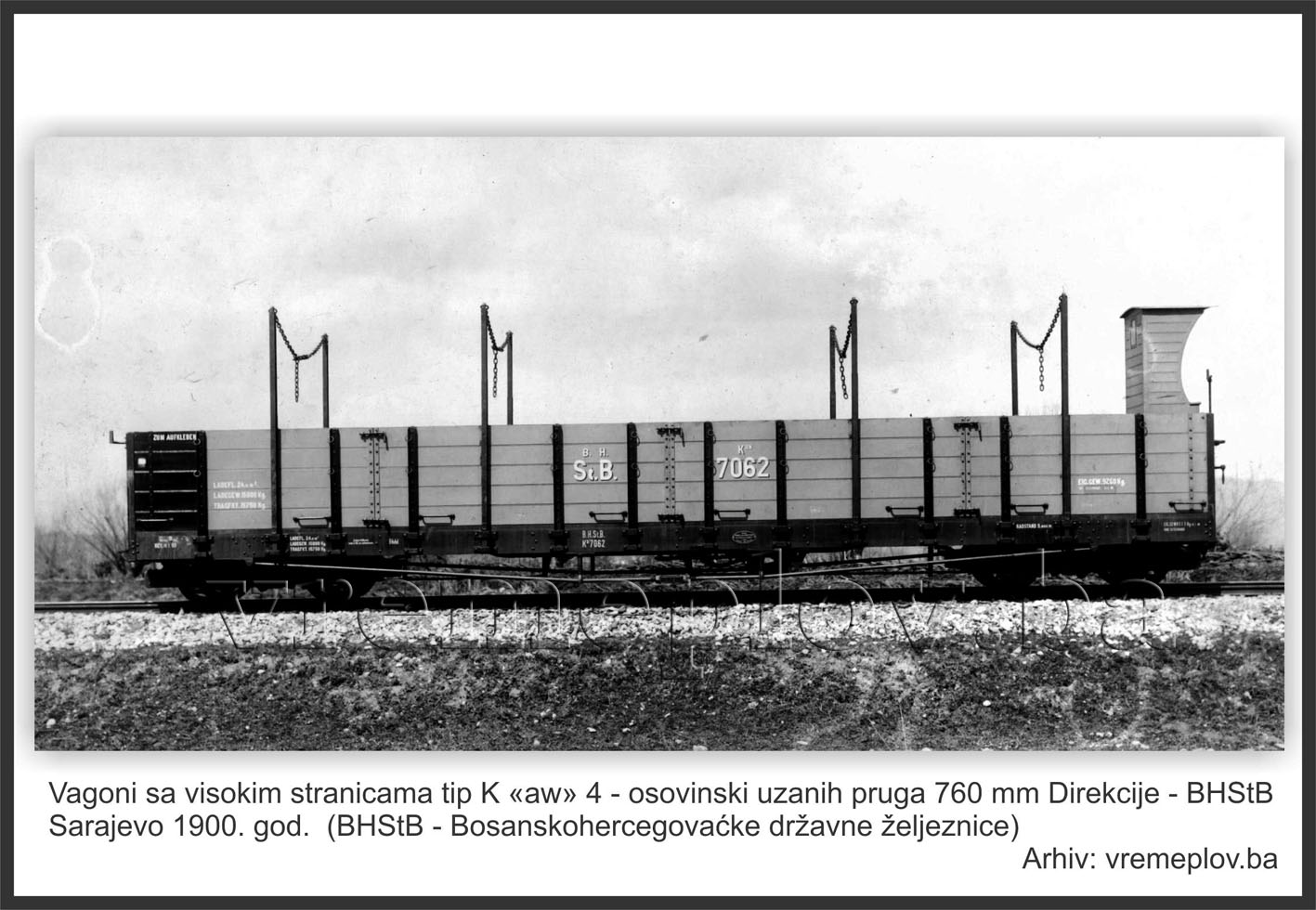

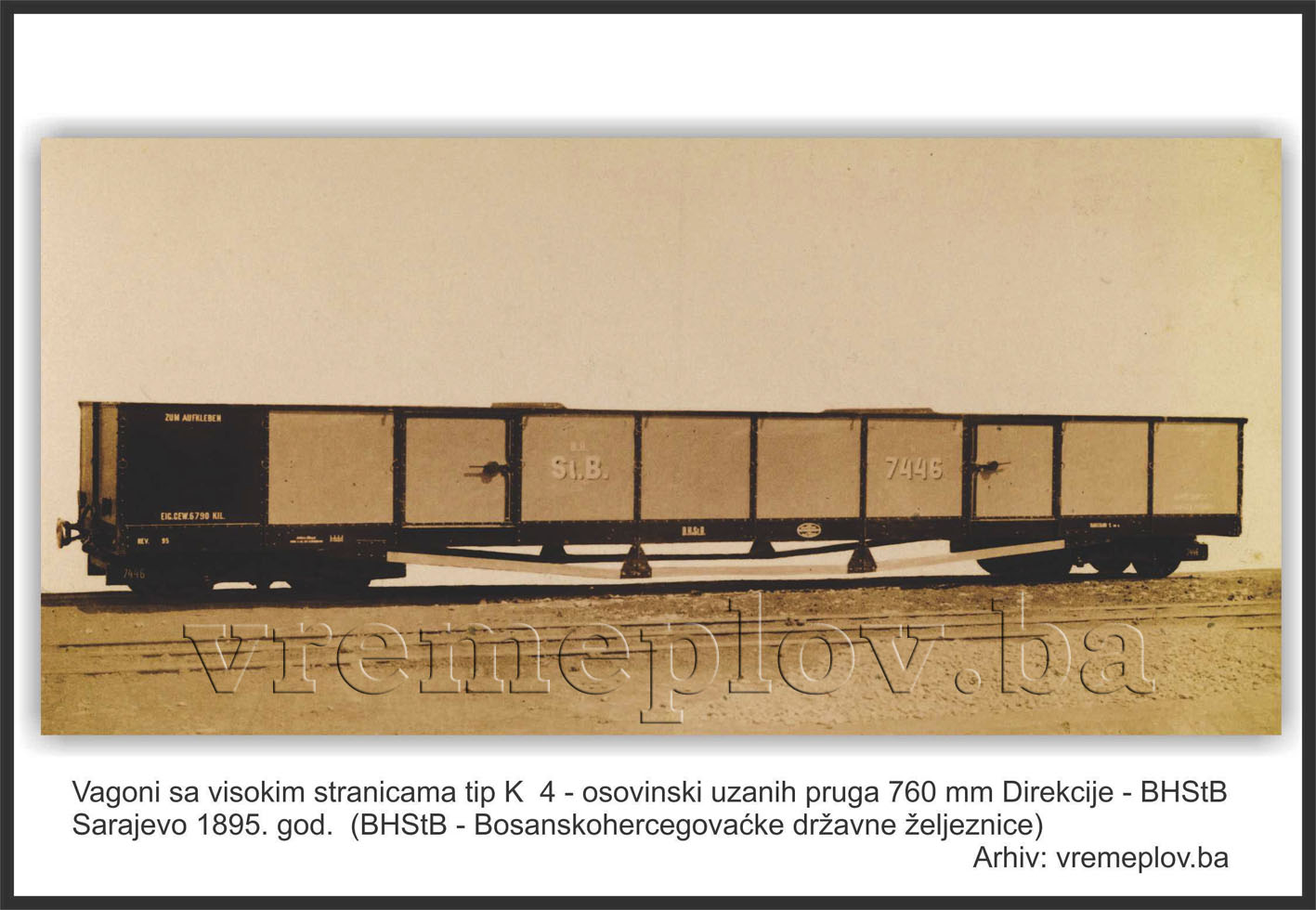

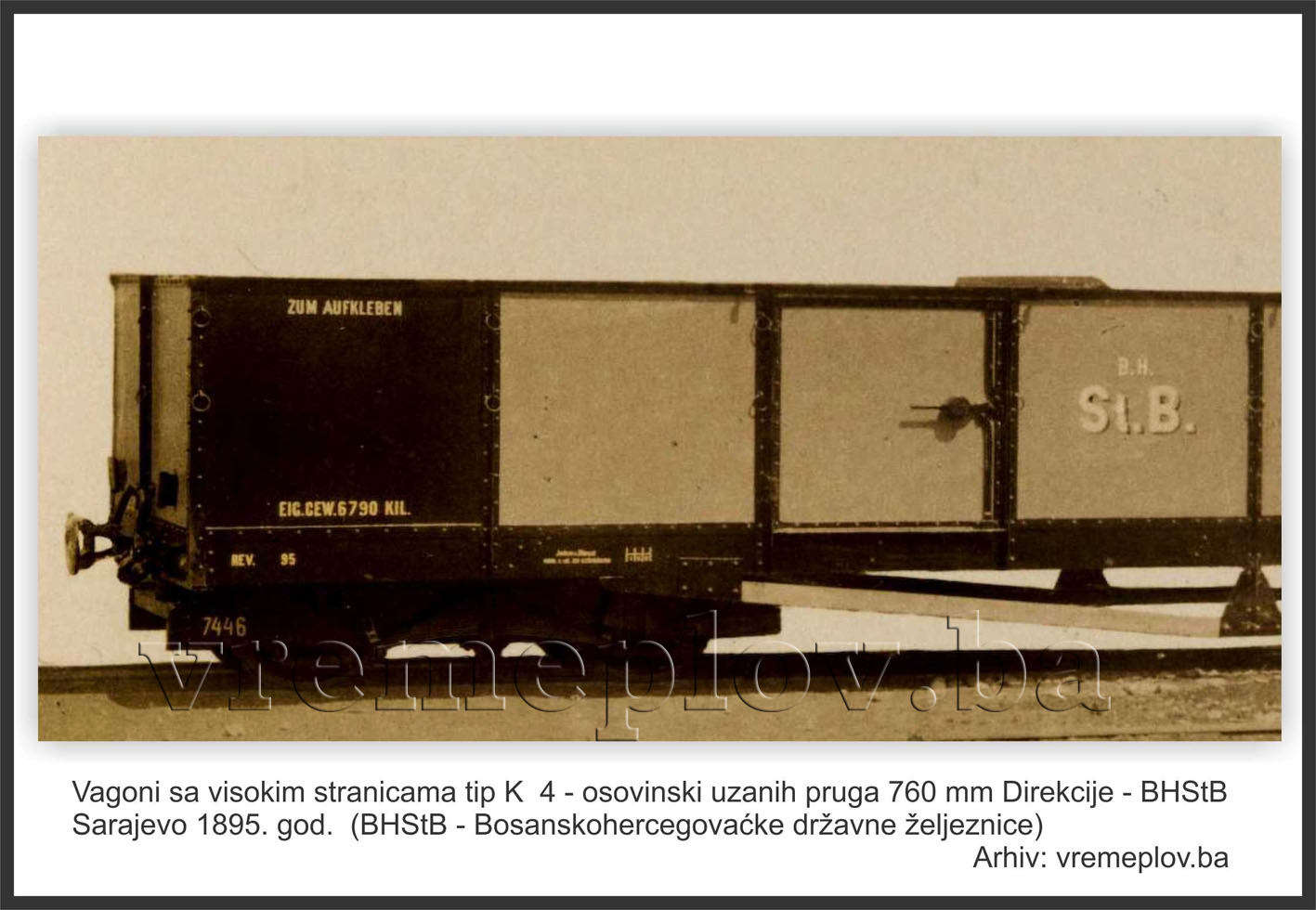

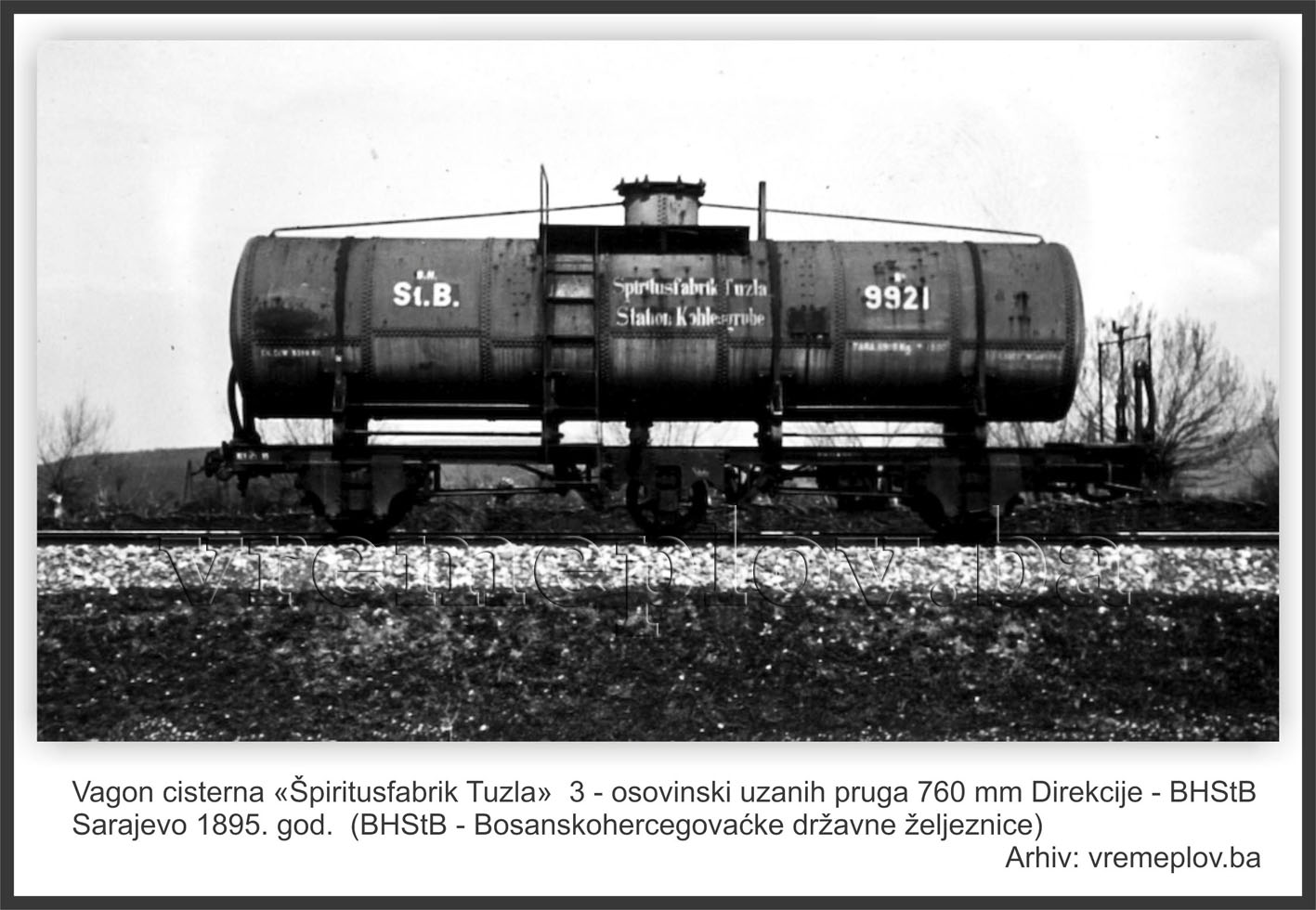

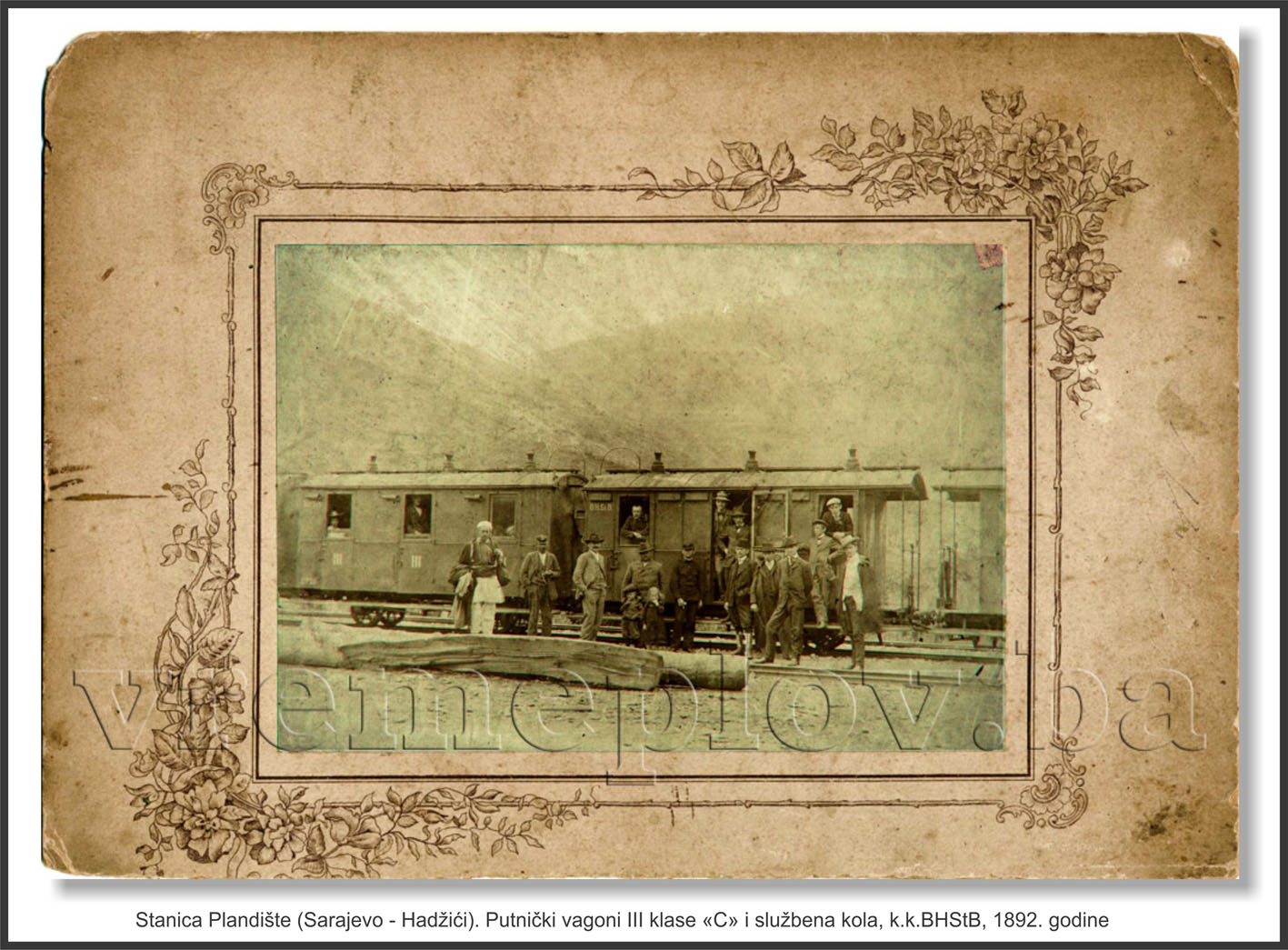

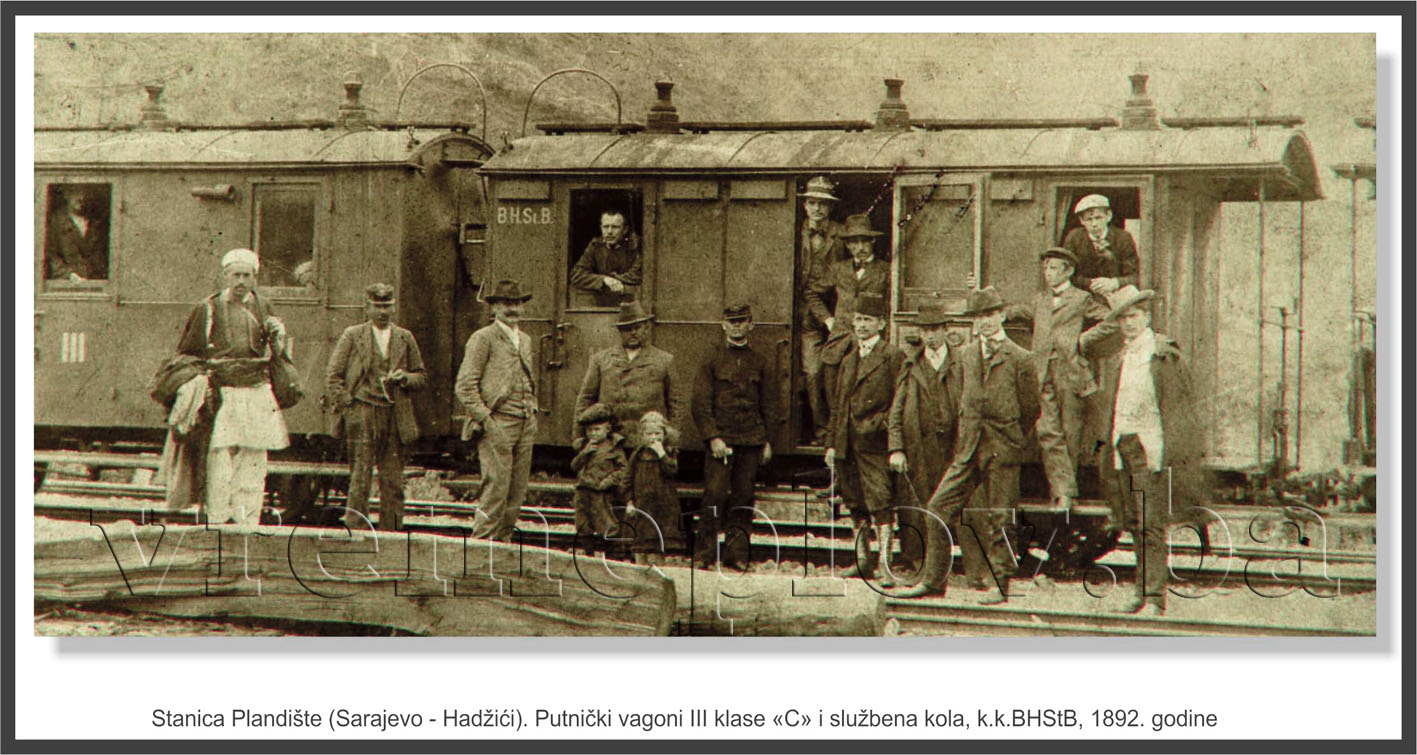

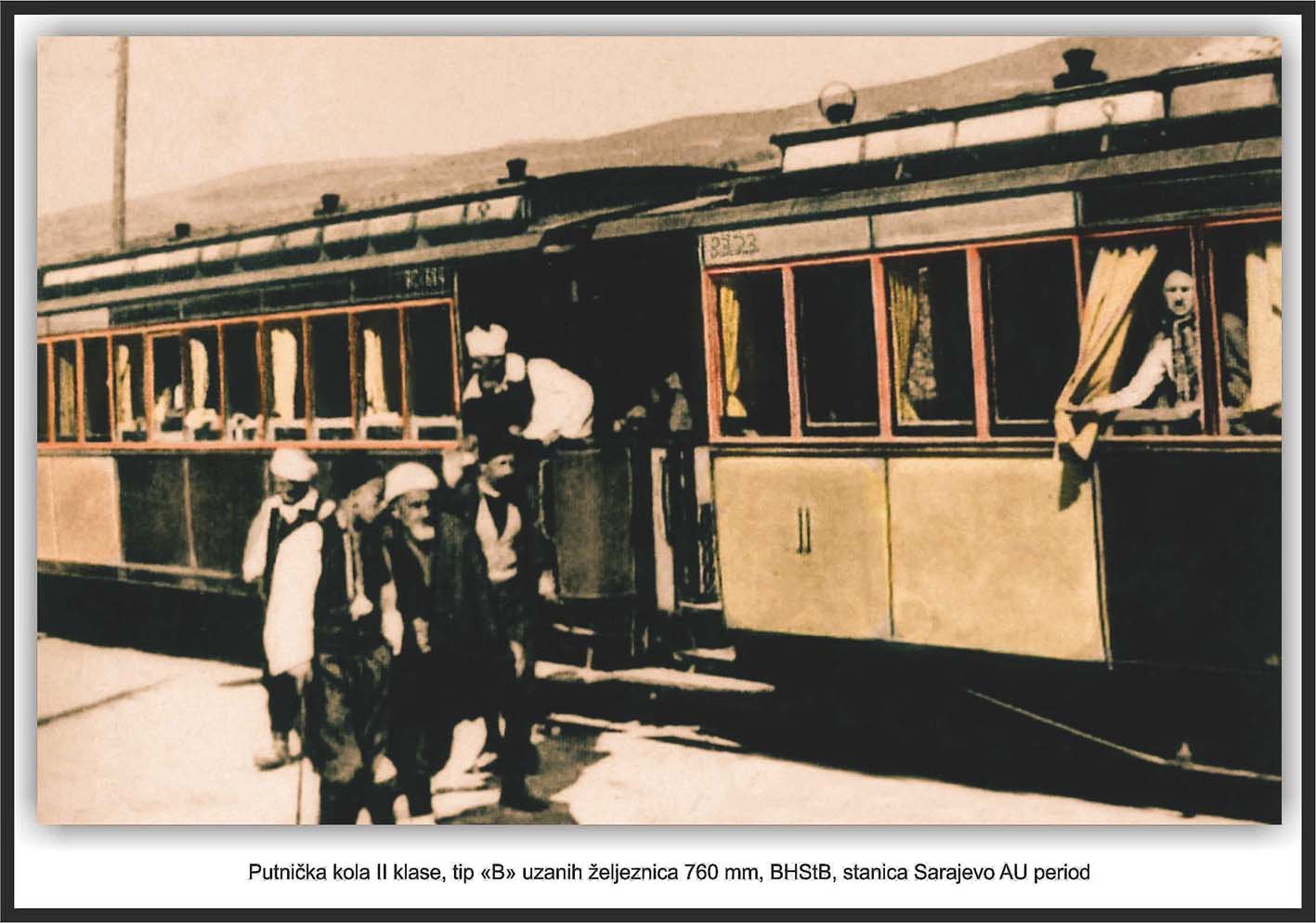

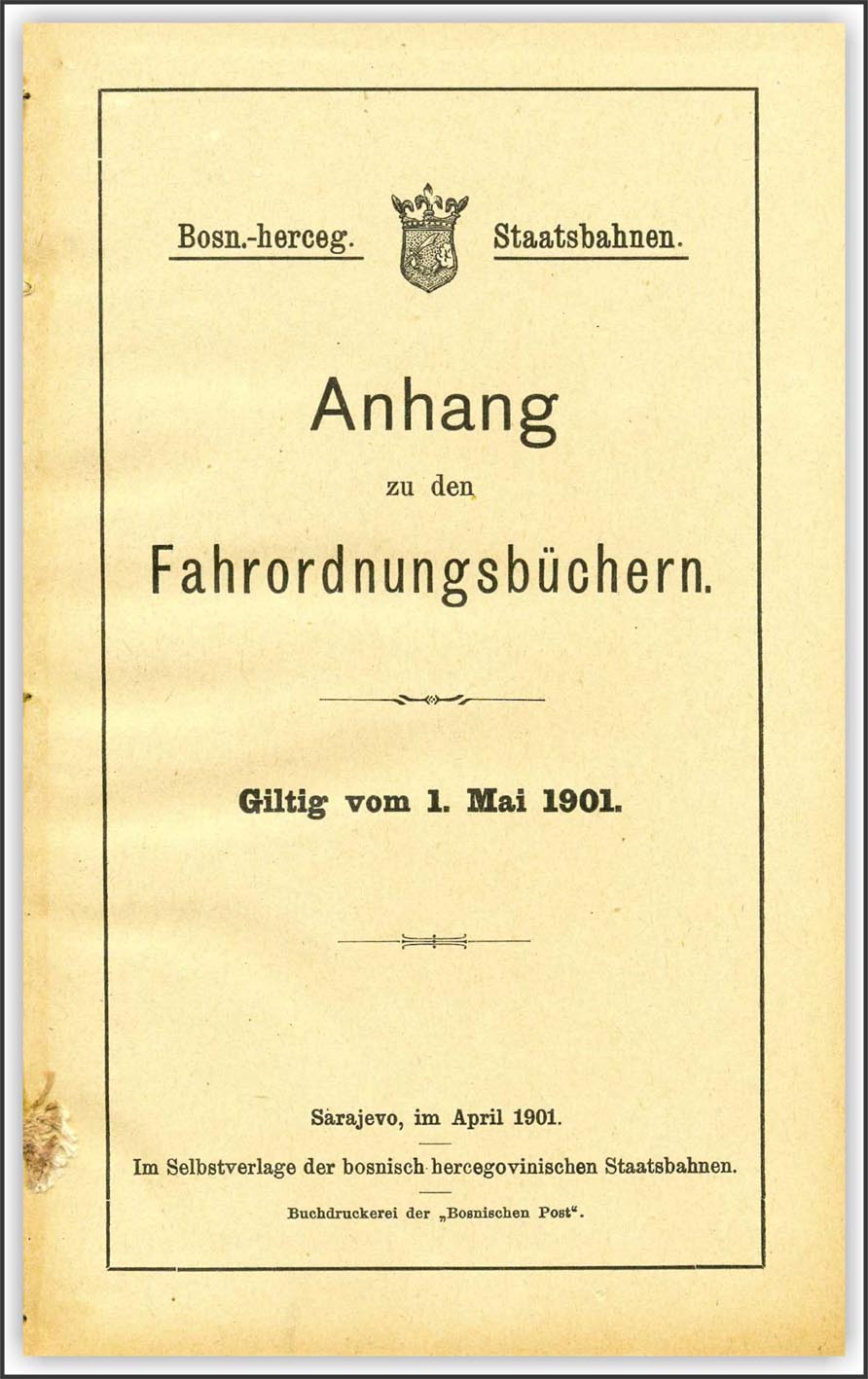

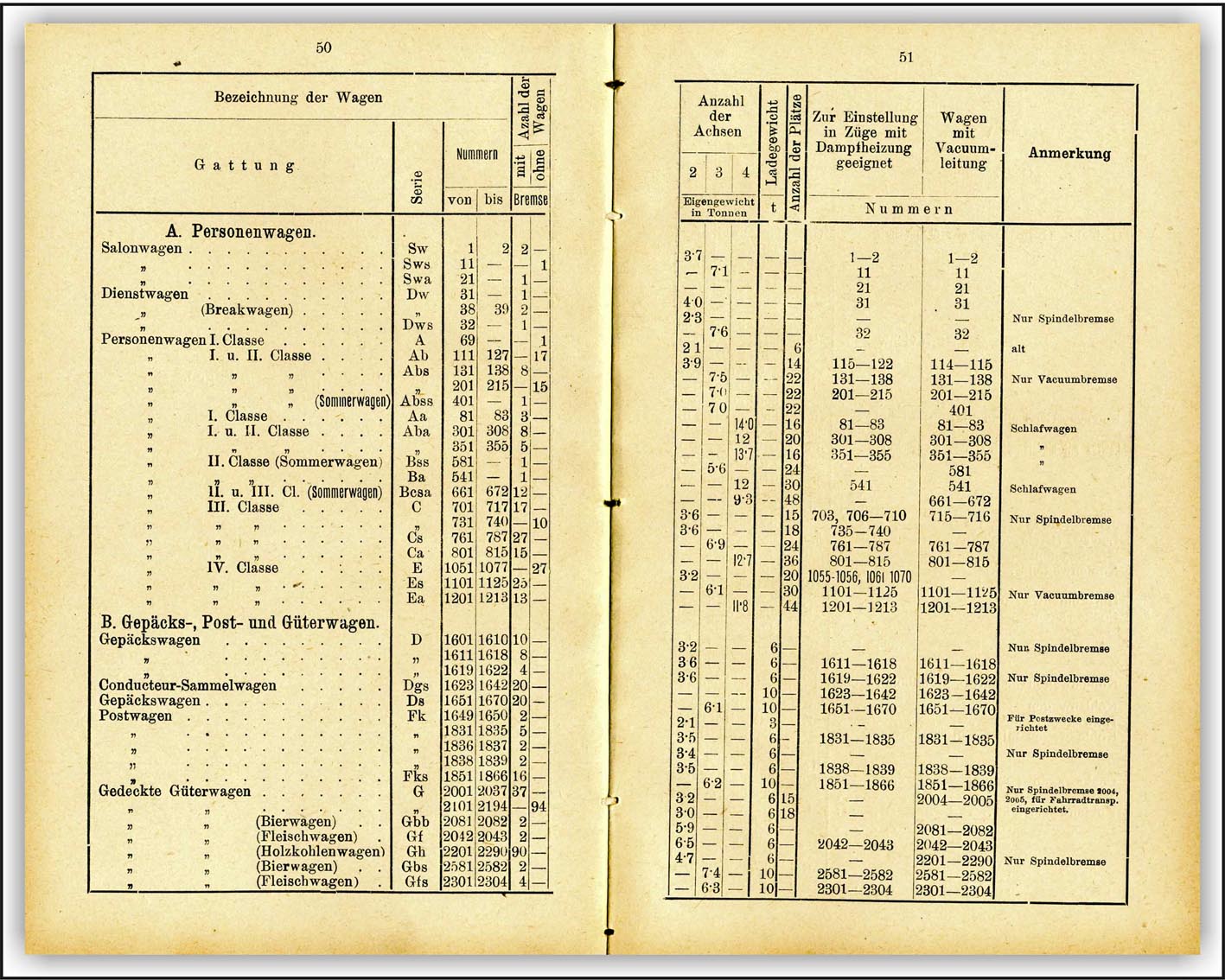

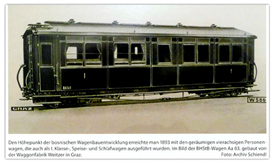

After one year, conditions improve as new and more powerful locomotives are introduced into traffic, along with new two-axle and three-axle passenger carriages of the first, second, and third classes, as well as two-axle carriages of the fourth class. The establishment of the railway directorate k. und k. Bosna-Bahn (Imperial and Royal Bosnian Railways 1879–1895), then k. und k. BHStB (Imperial and Royal Bosnian-Herzegovinian State Railways 1895–1908), and BHLB (Bosnian-Herzegovinian Land Railways 1908–1918) marks even greater progress in the rolling stock for passenger and freight traffic. Specifically, the peak of passenger traffic development was achieved in 1893 when new four-axle carriages designed as first class, a combined first and second class, followed by dining cars and sleeping cars, were introduced into operation. Already by 1908, the passenger transport sector of the BHLB Directorate expanded its “modern” fleet with new four-axle passenger carriages called “Kaiservagen” (Imperial carriages – a court train used during the visit of Emperor Franz Joseph to Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1910) and several luxury (salon) cars of the first and second classes, generally for affluent tourist clientele on the route Brod – Sarajevo – Dubrovnik / Herceg Novi.

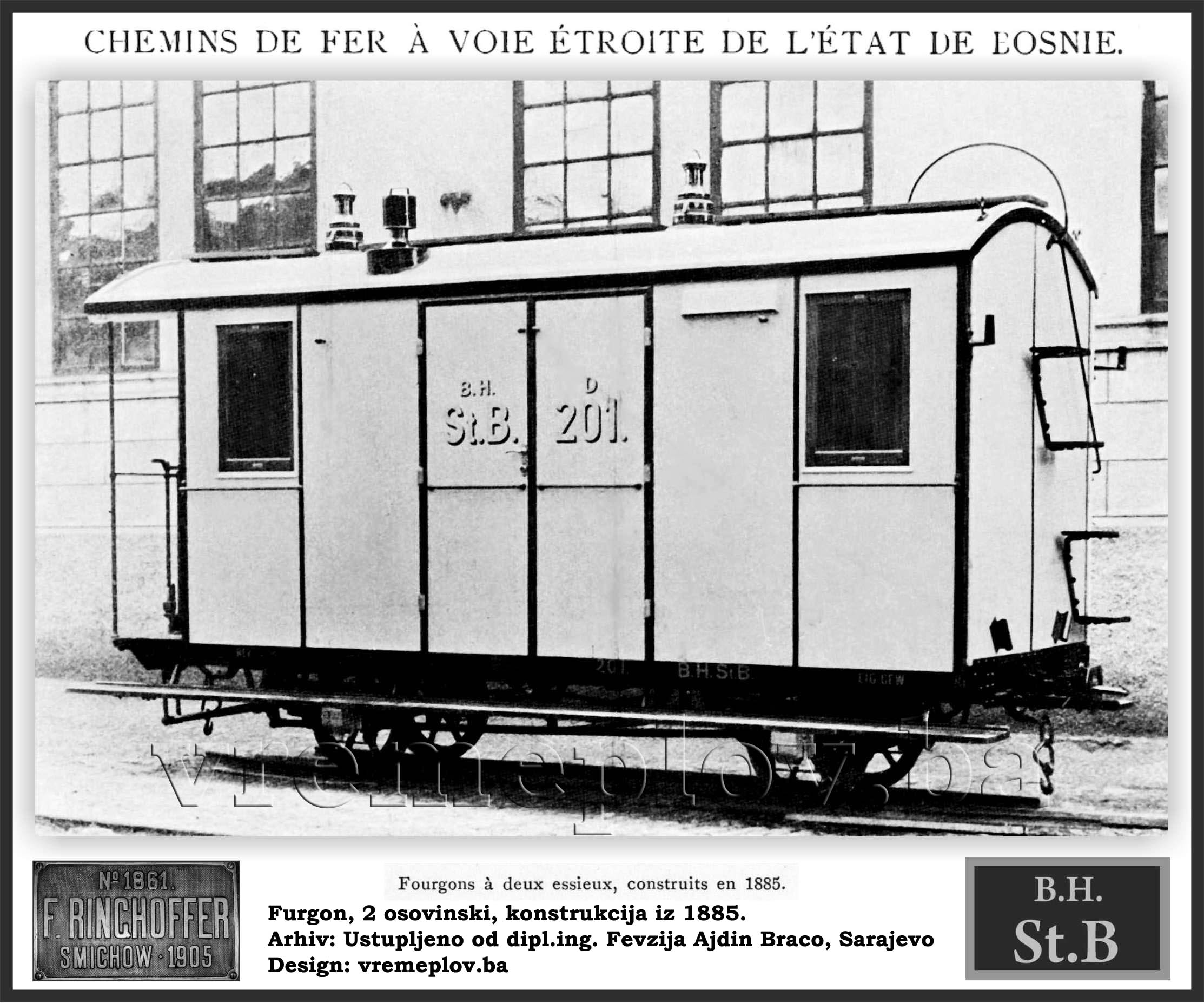

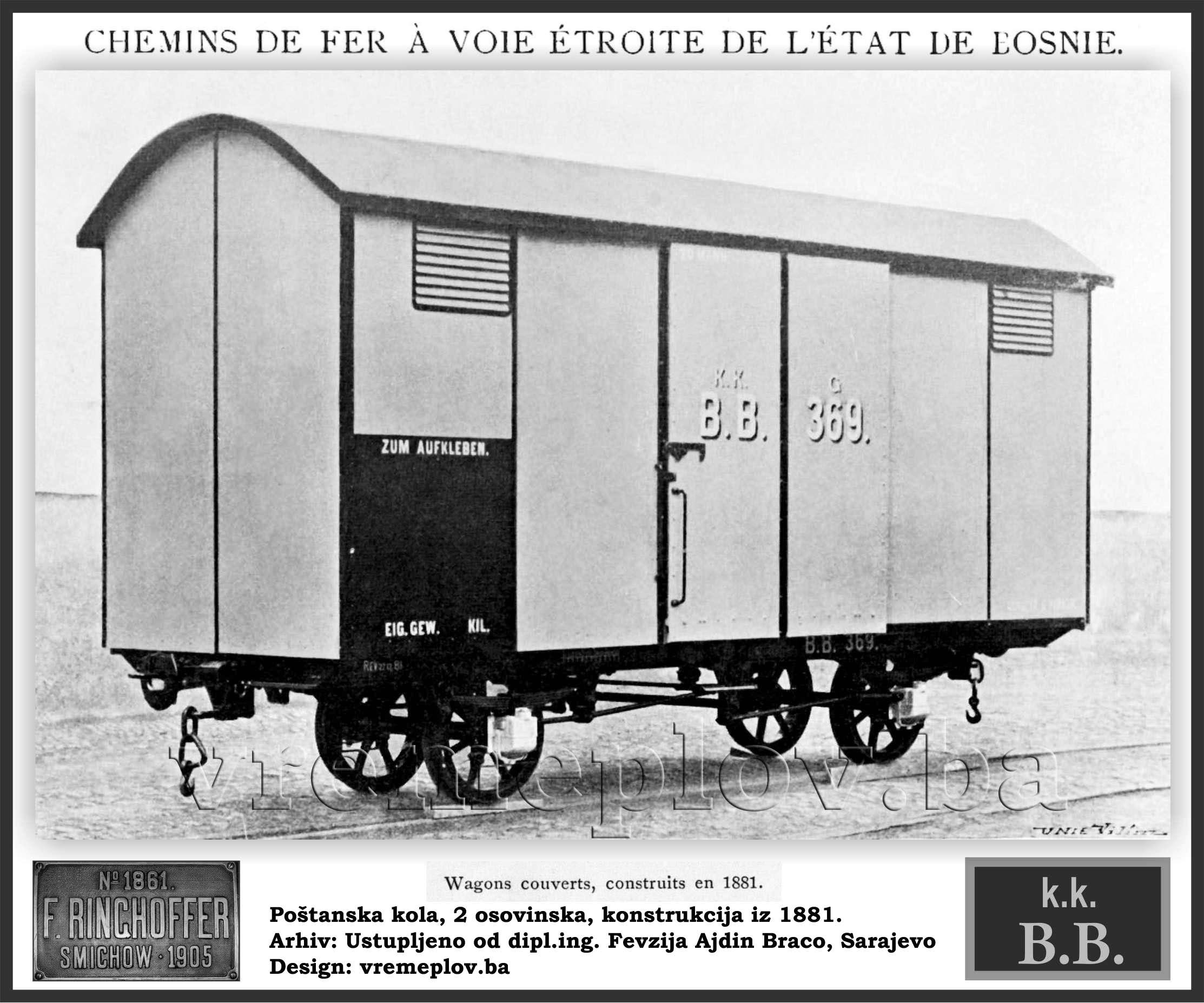

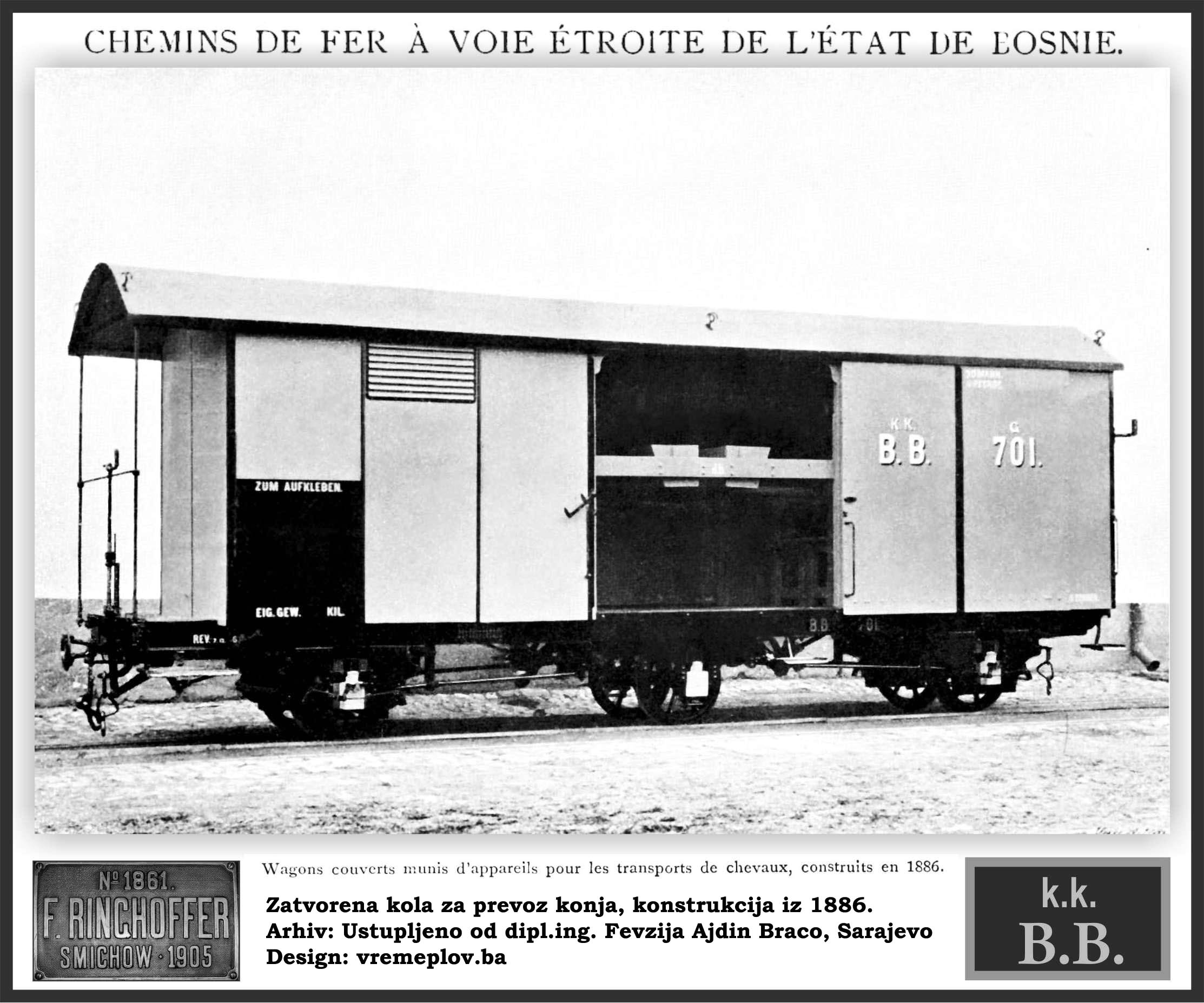

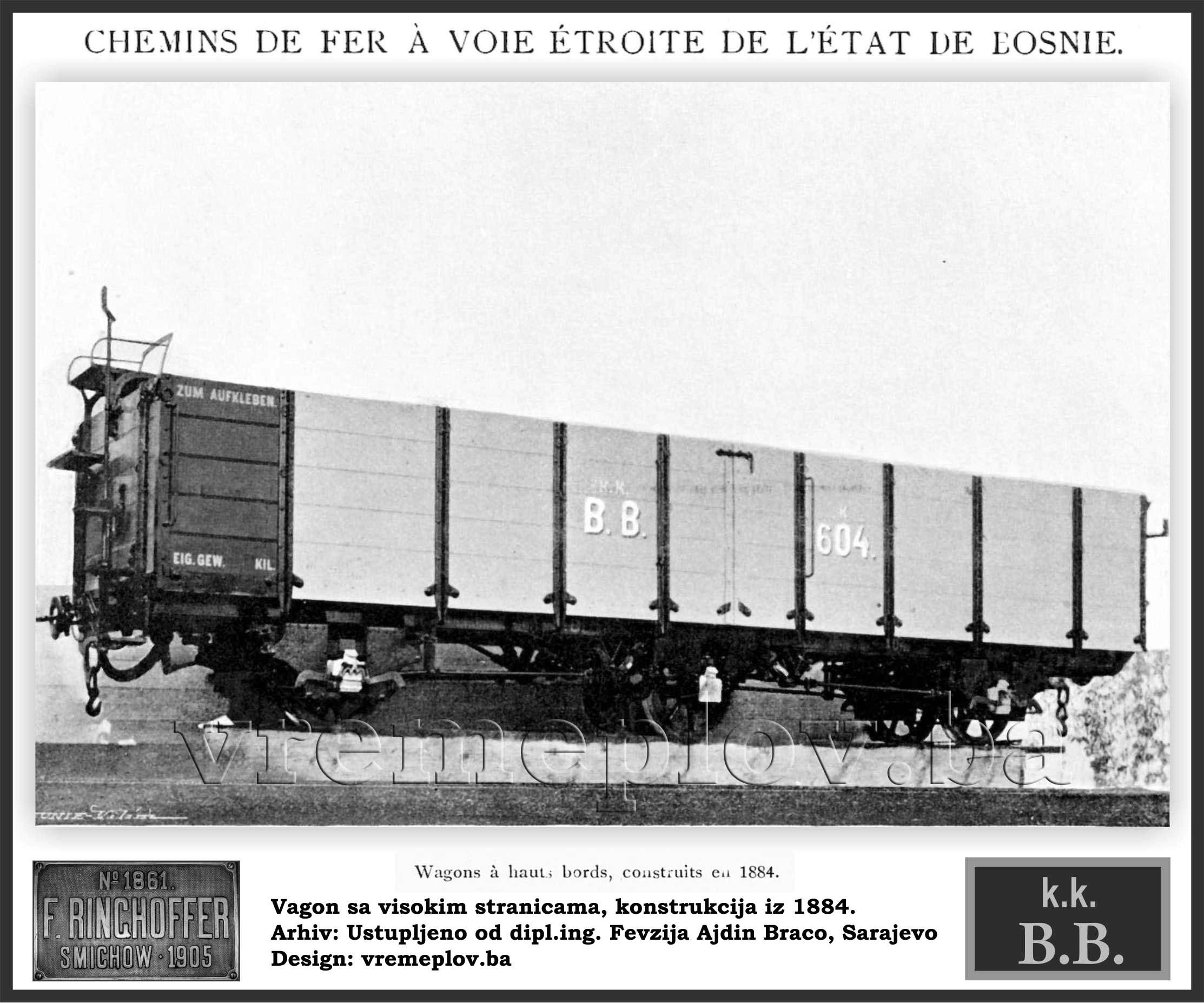

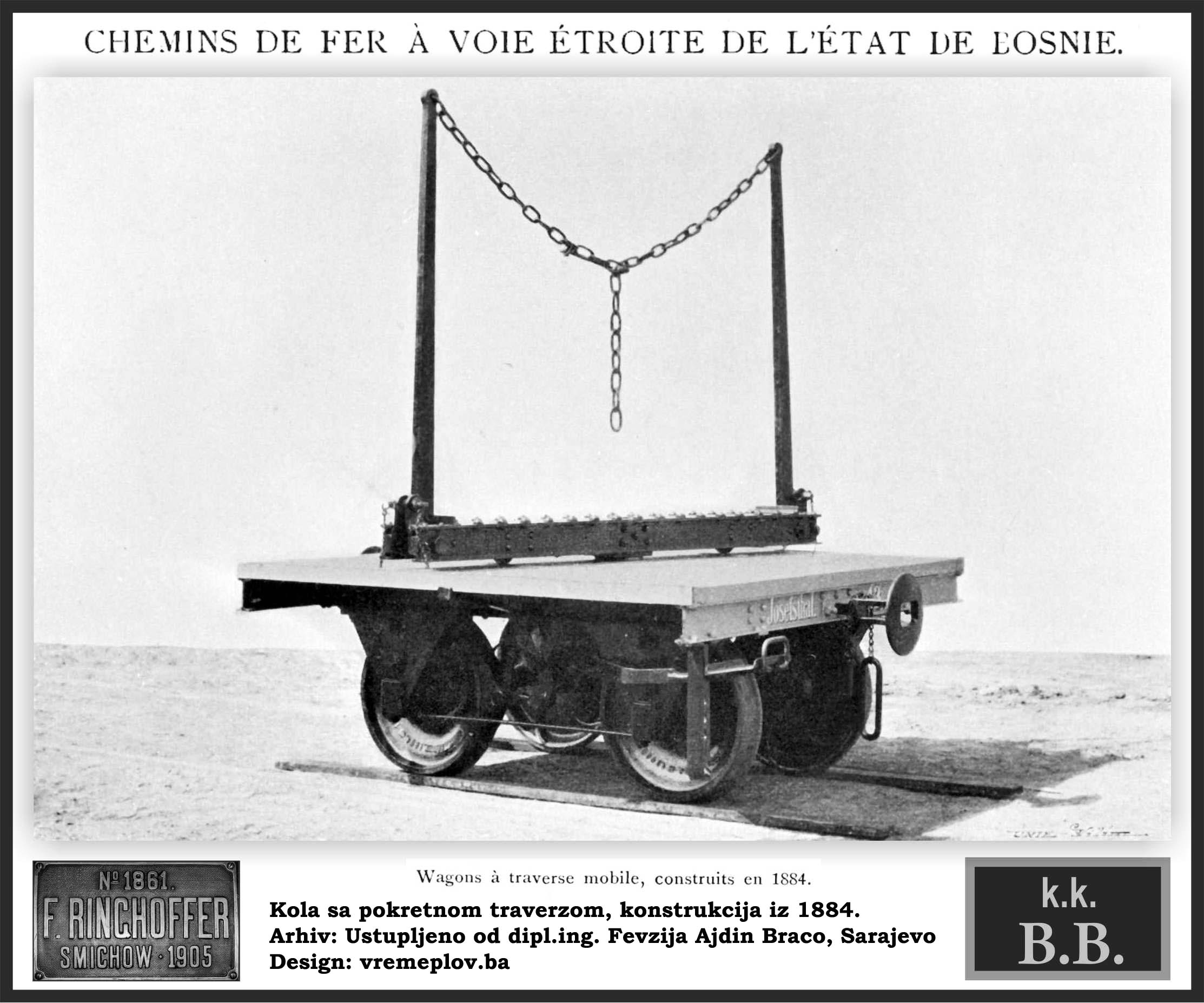

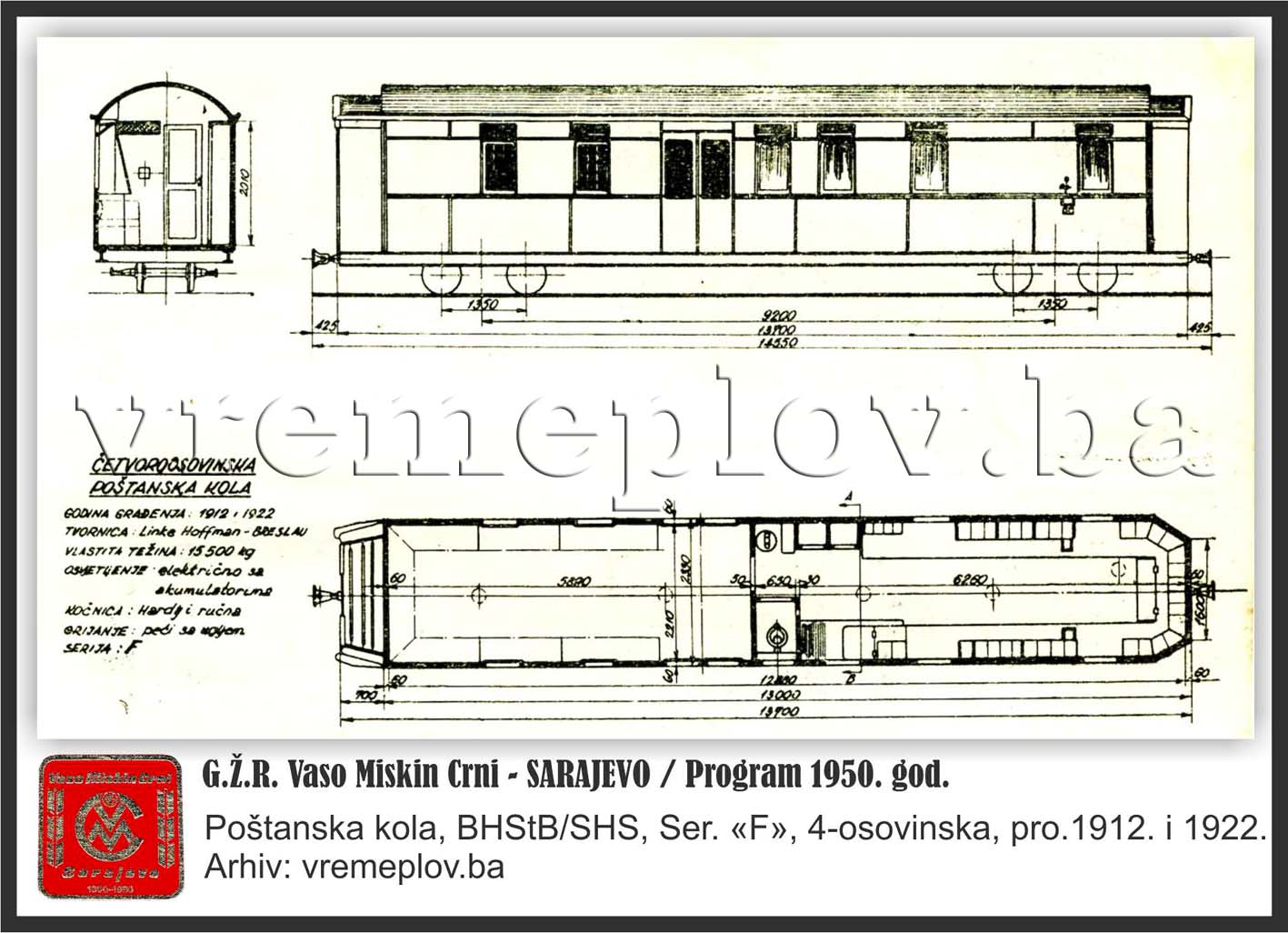

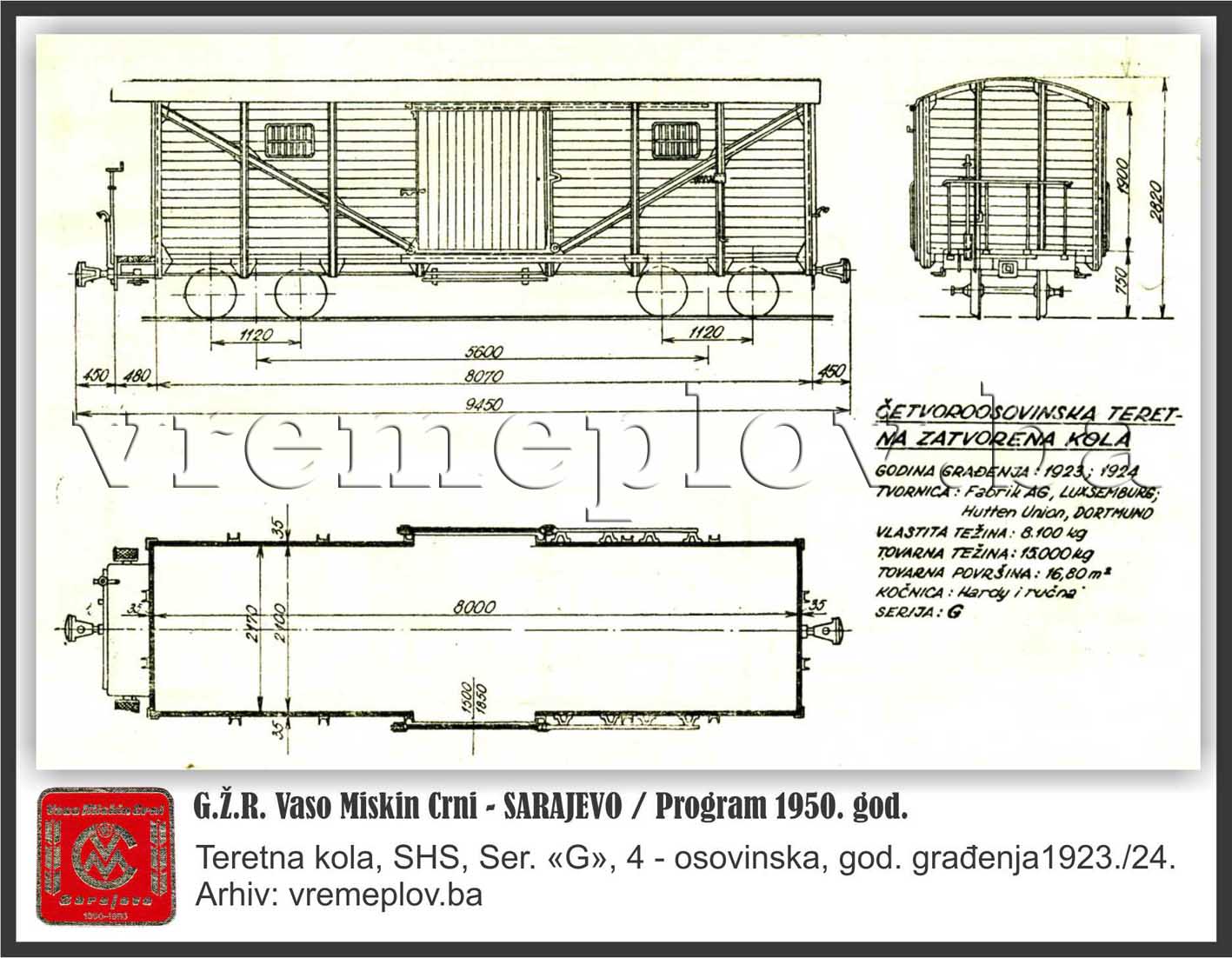

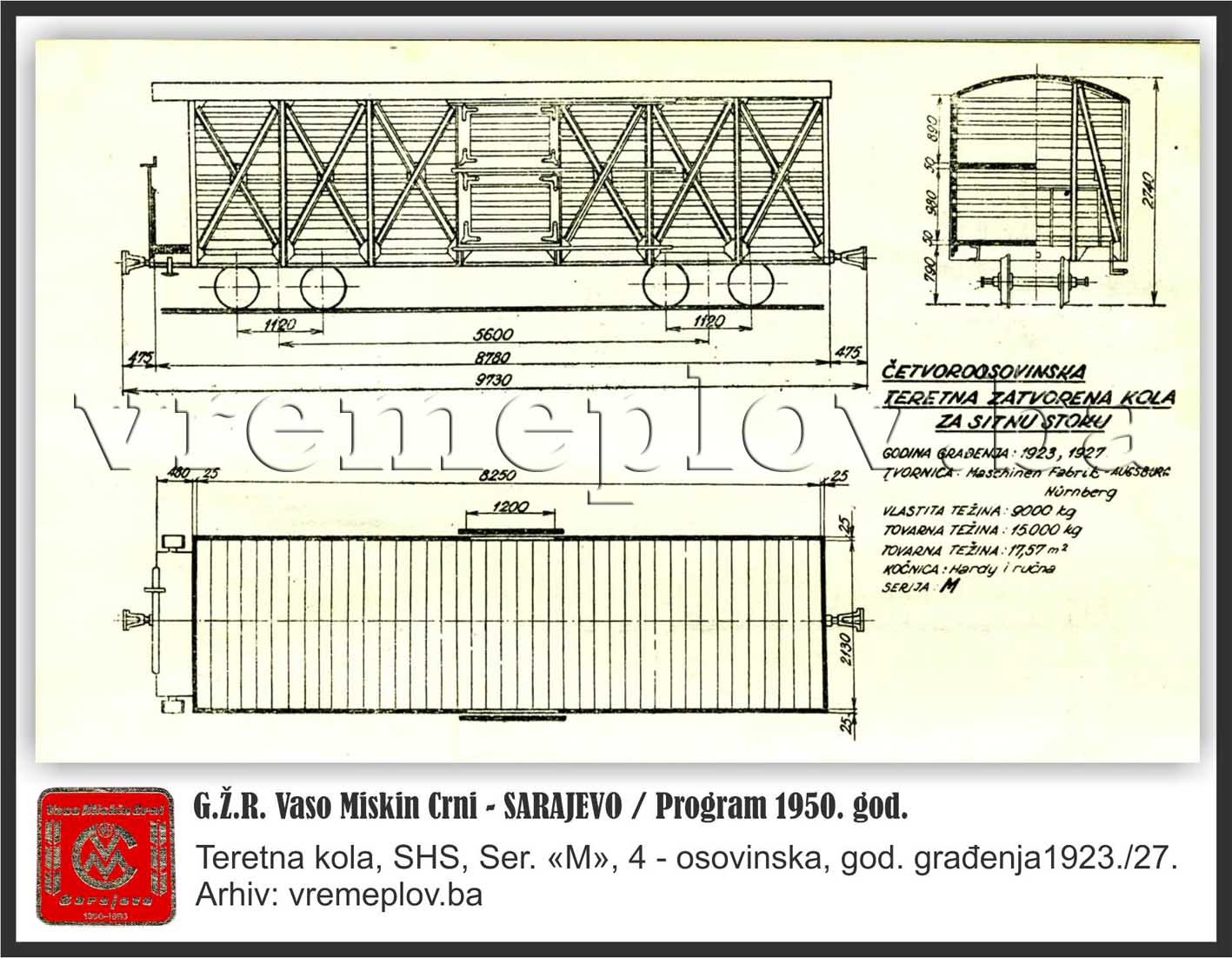

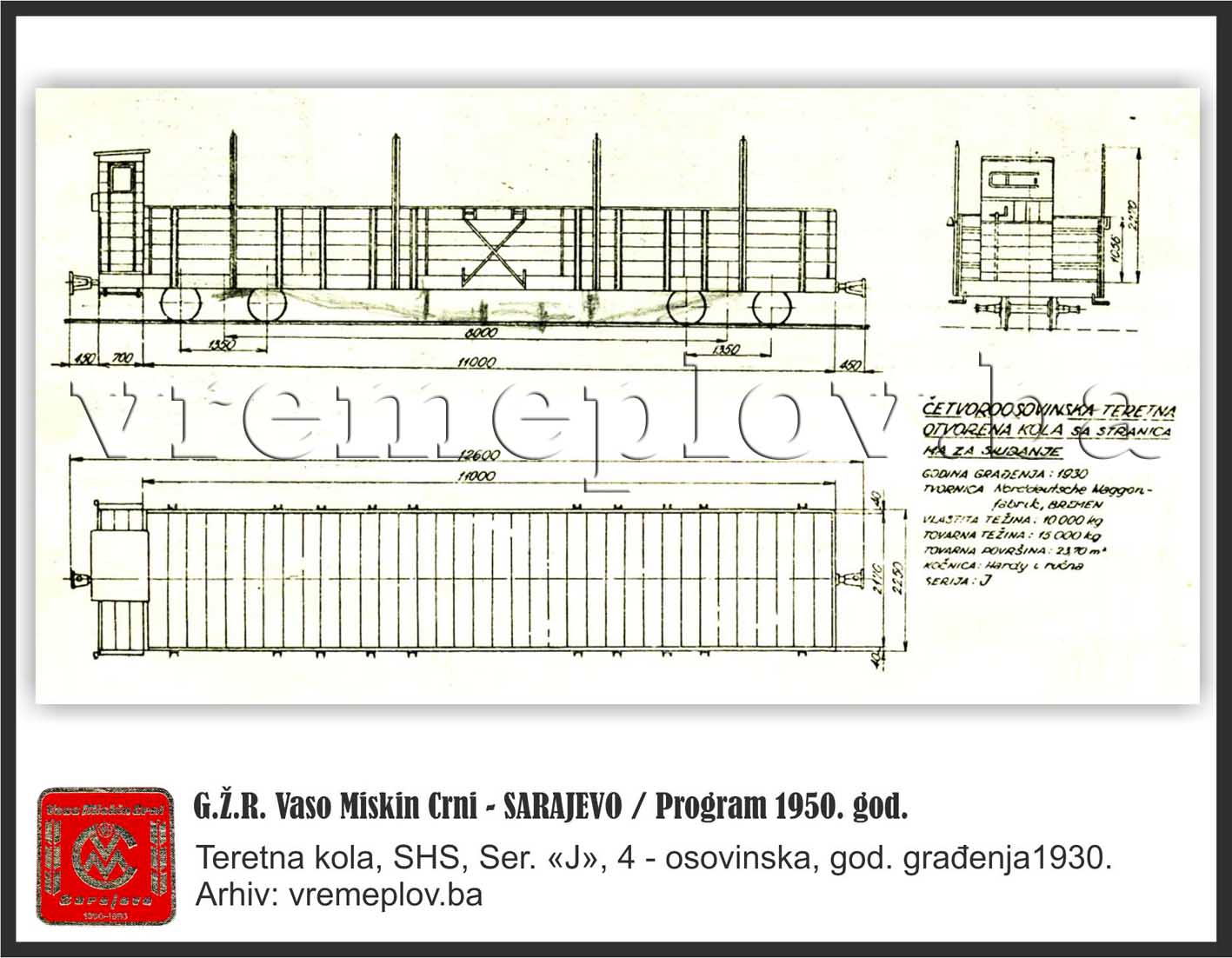

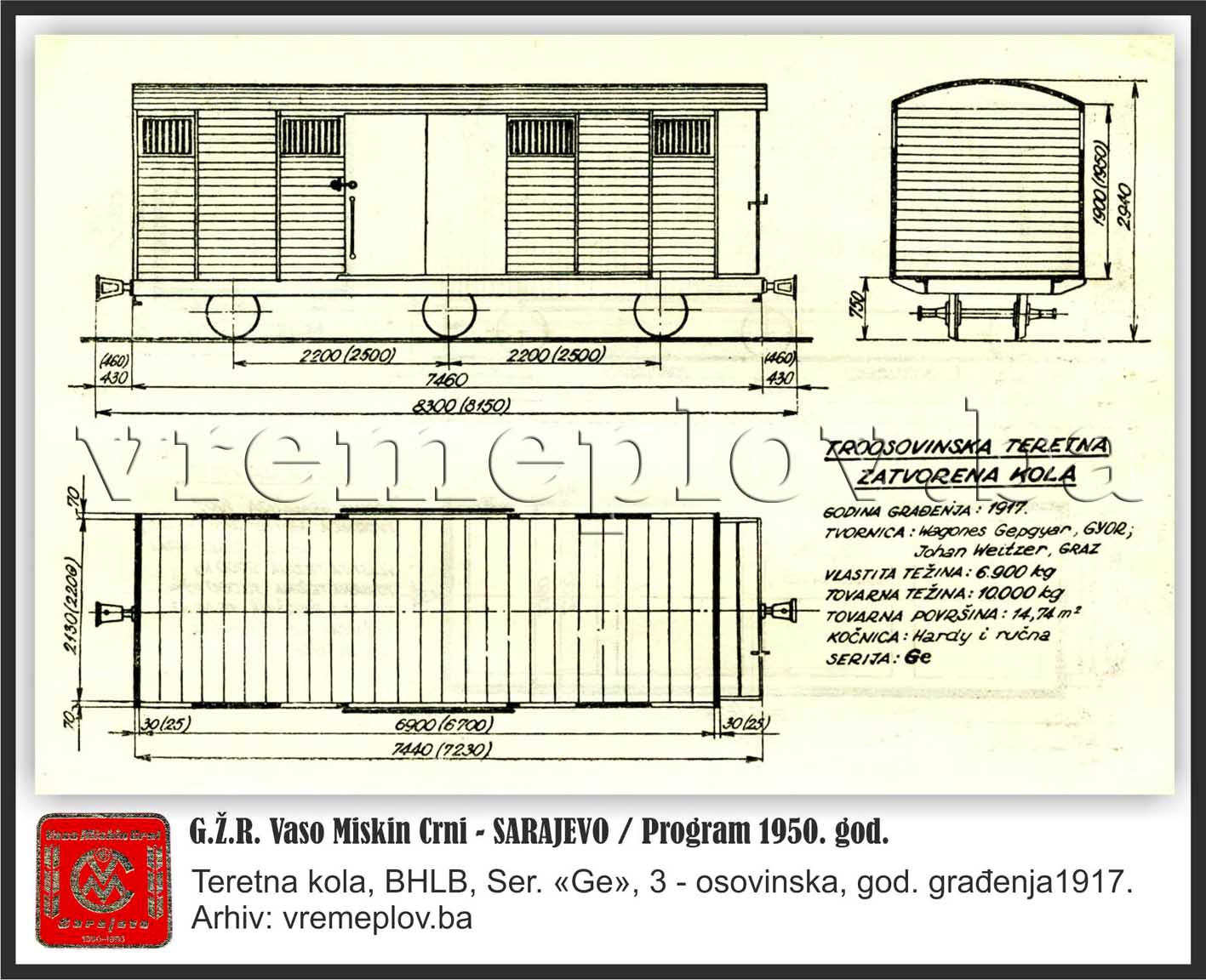

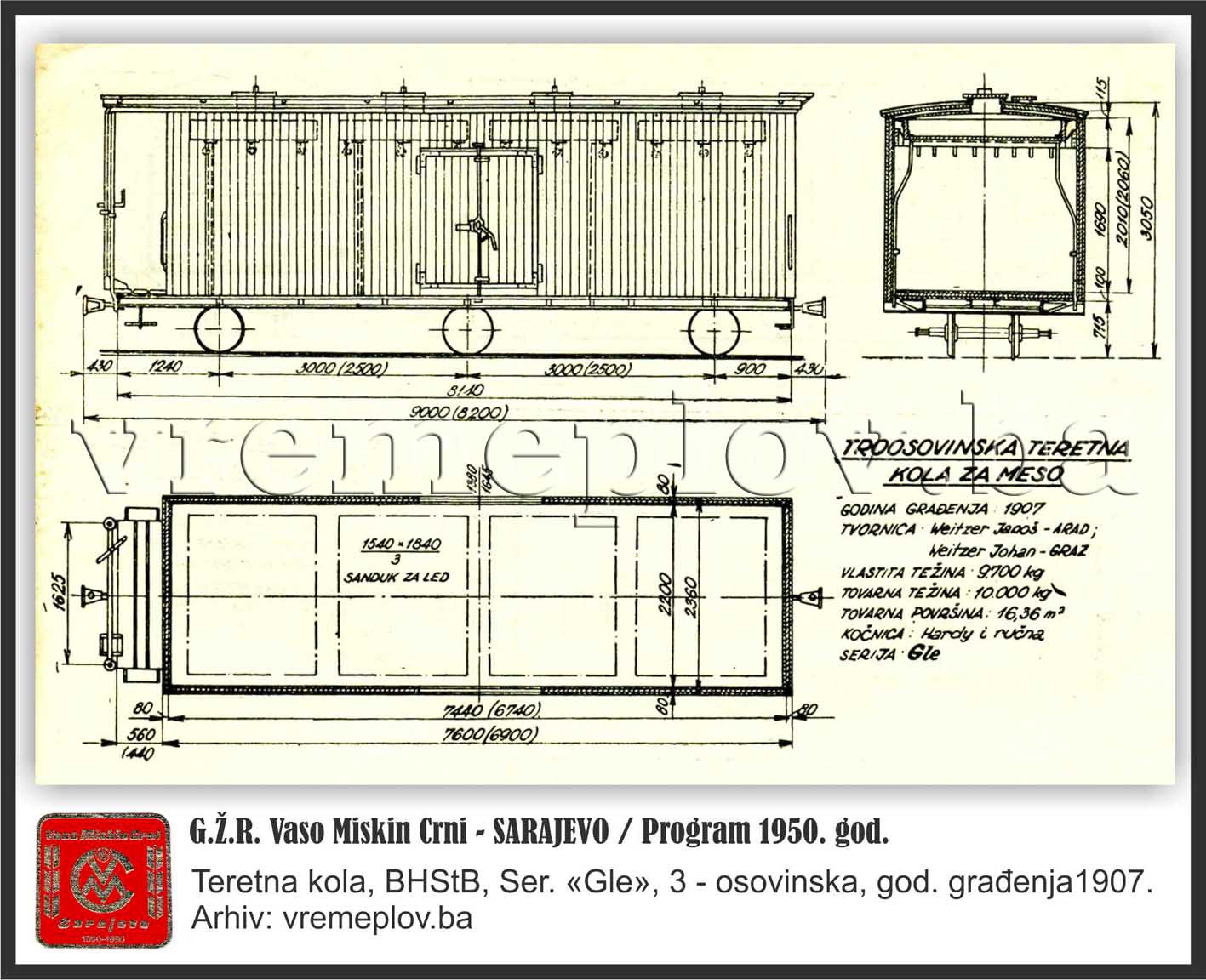

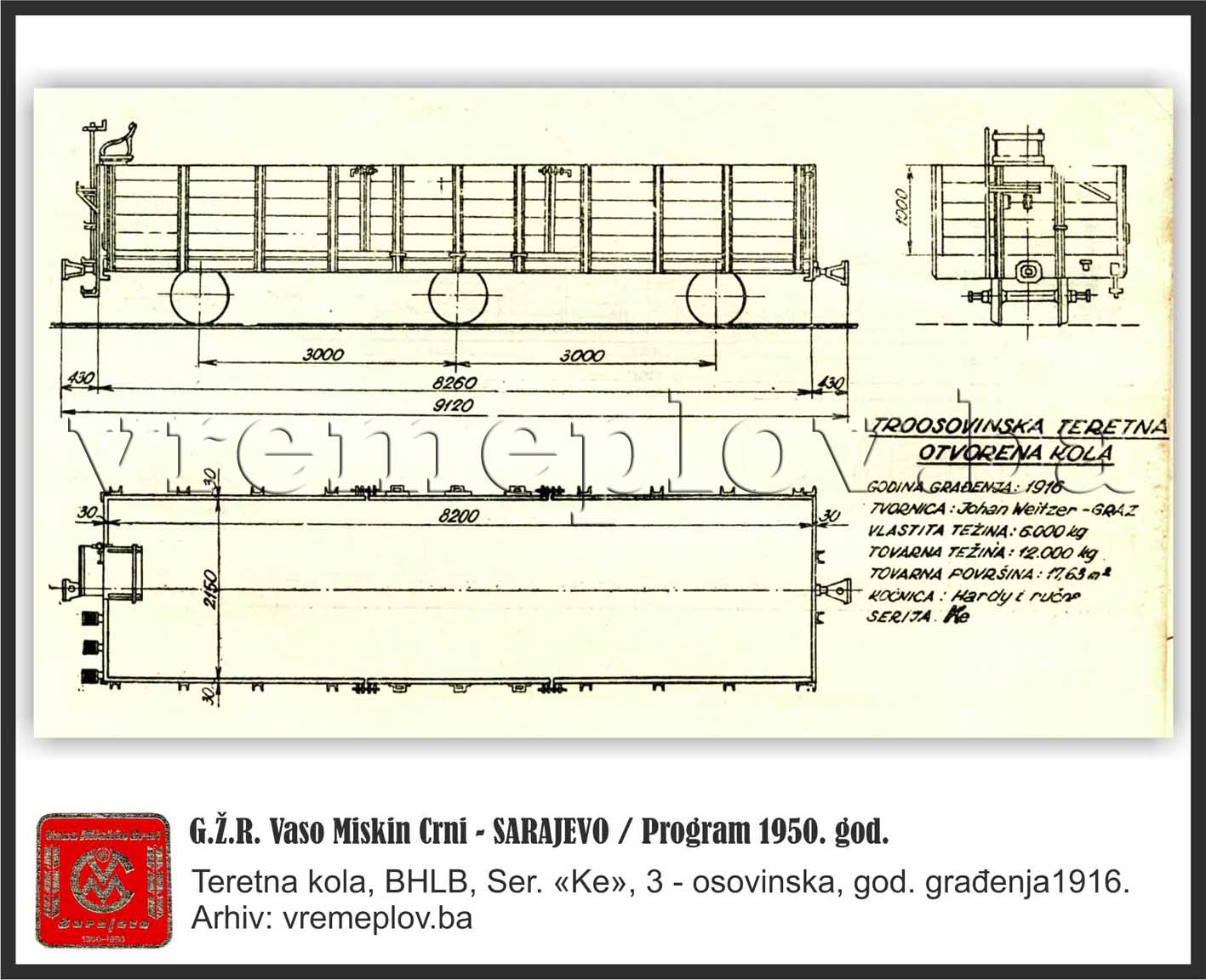

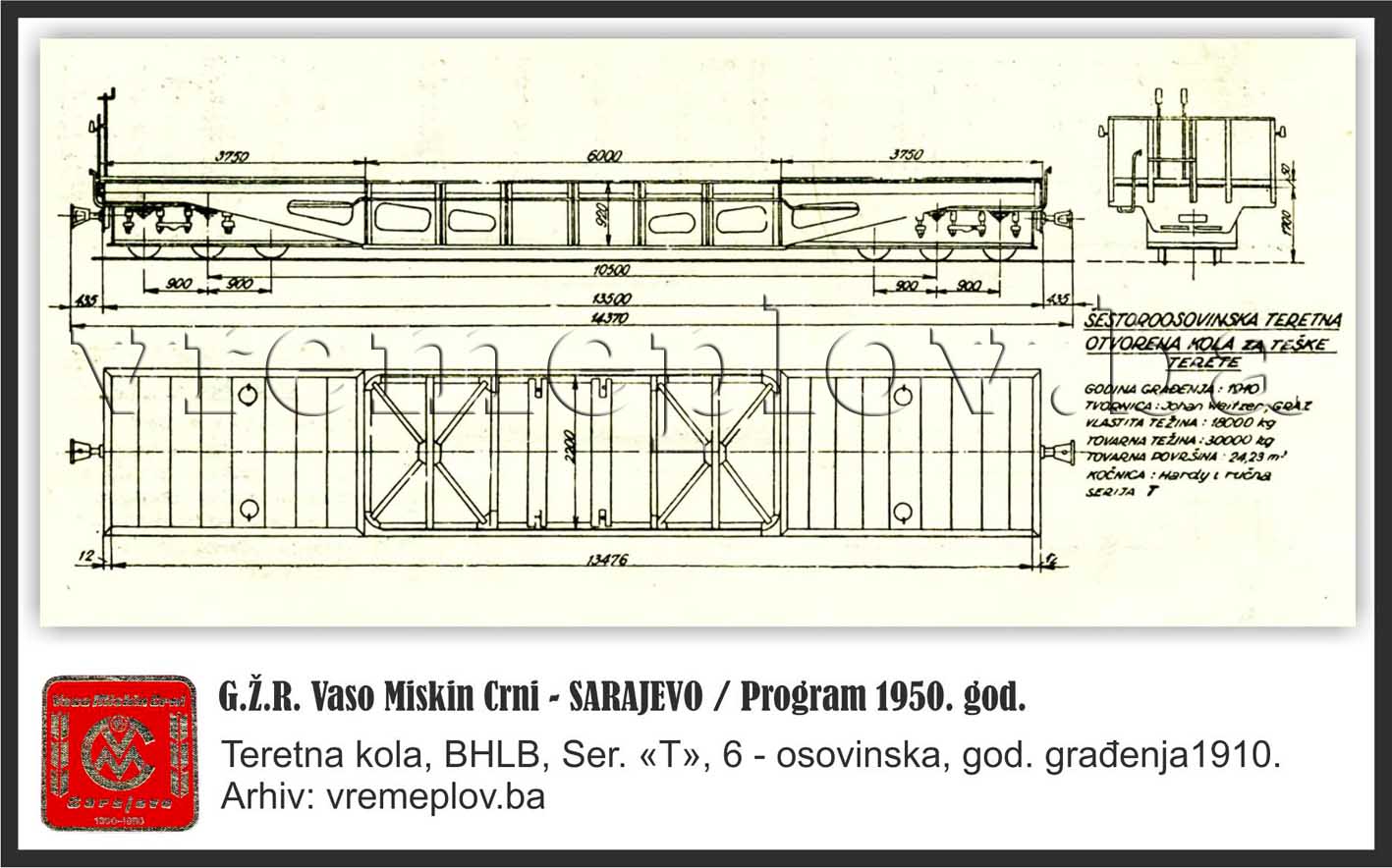

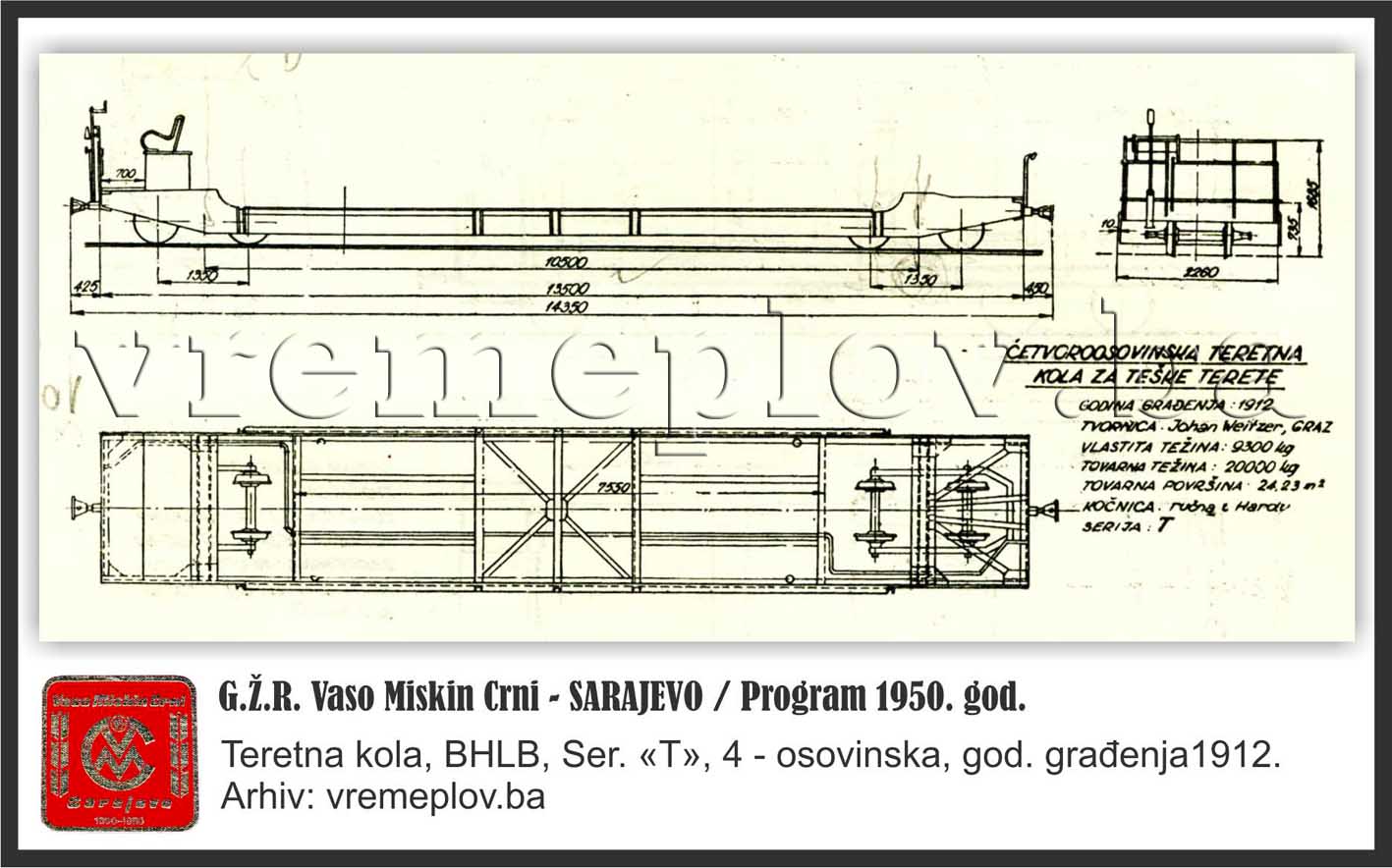

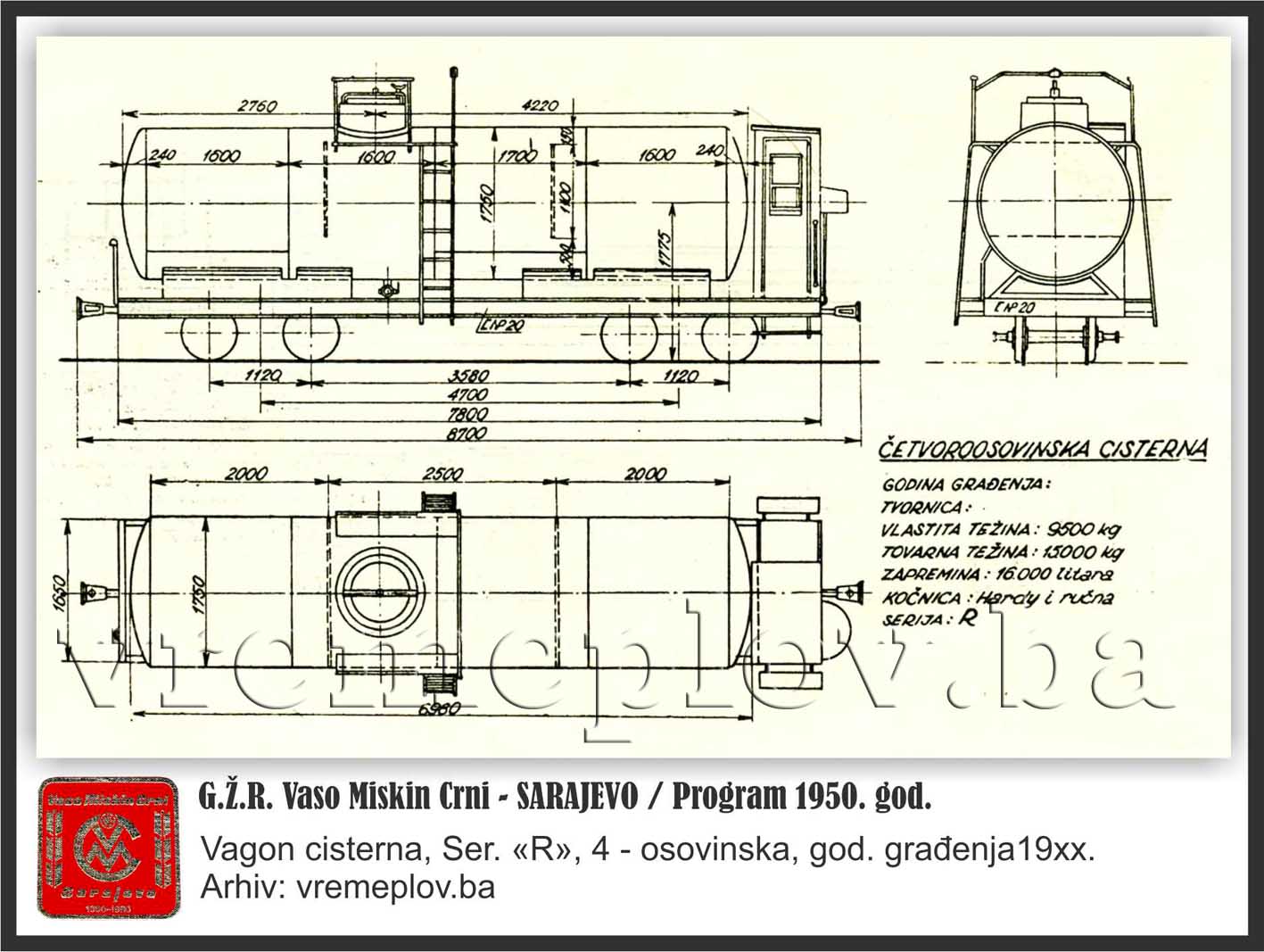

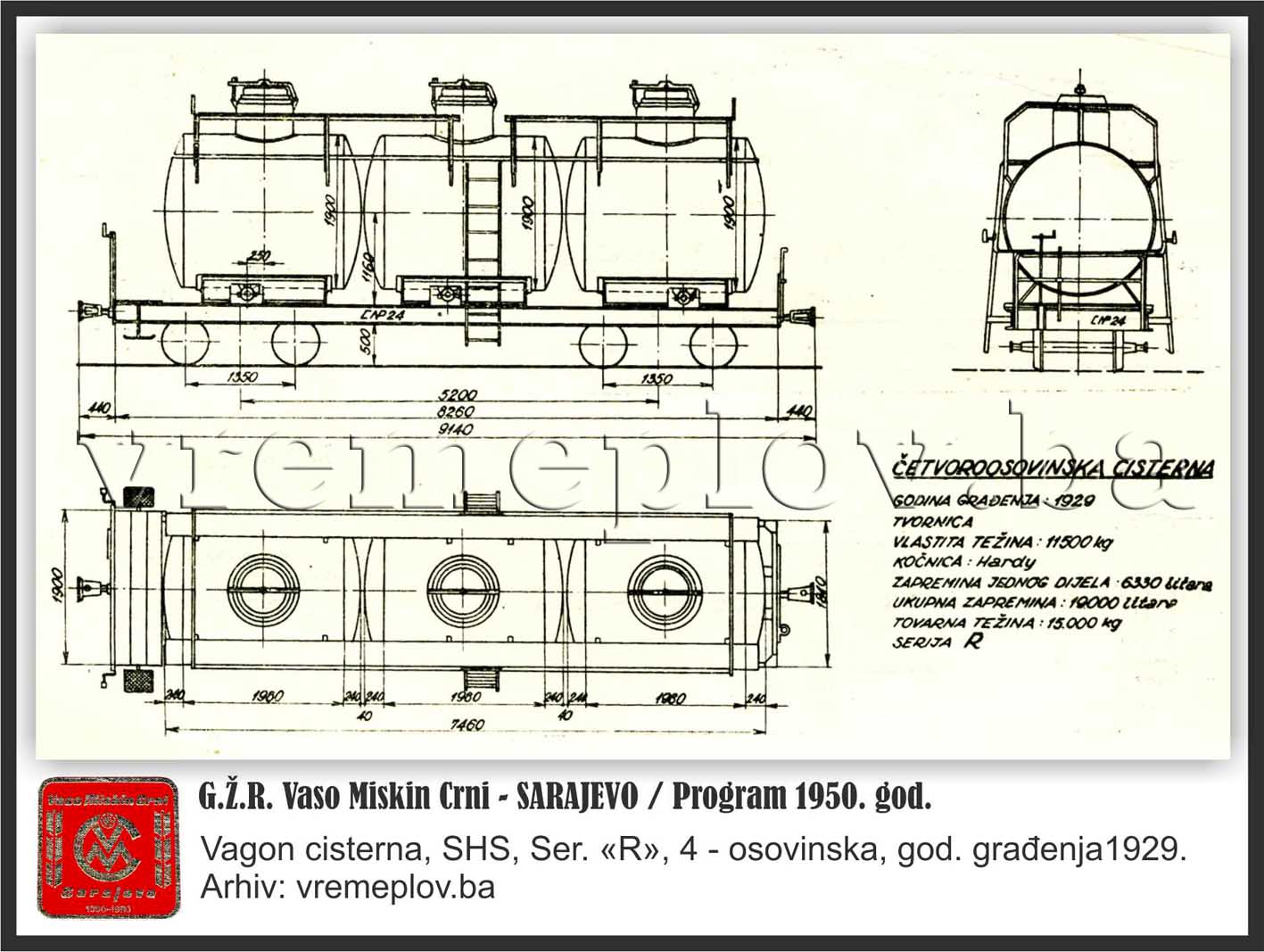

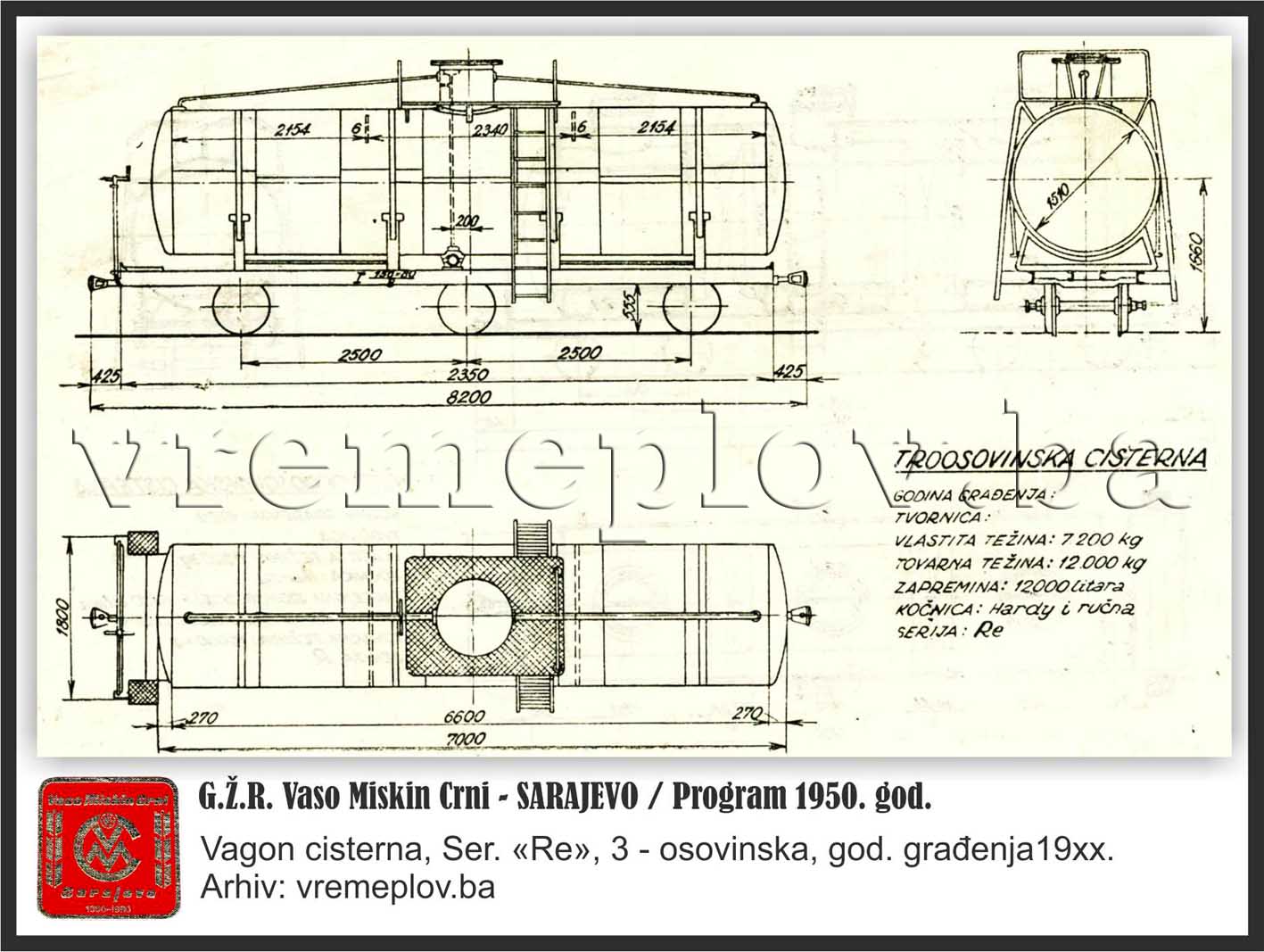

Passenger and freight cars are acquired from factories in Austria, Hungary, Germany, and the Czech Republic. Here are some of these factories: František Ringhoffer Wagon and Tramway Factory – Smichov, Czech Republic, Johann Weitzer – Graz, Weitzer – János – ARAD (Grazer Wagon- und Maschinenfabr A. G. formerly Joh.), Gepgyar Wagon Factory – Gyor (“Magyar Waggon- és Gépgyár Részvénytársaság” – Hungarian Waggon & Machine Company – Gyor), Norddeutsche Waggonfabrik – Bremen, Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg, Luxembourg Foundry Wies & Co. A.G., Hüttenunion AG – Dortmund, Linke-Hofmann – Breslau – Germany, Hernalser Wagon Factory – Vienna, Weitzer Wagon Factory – Graz, Slavonski Brod Wagon Factory, Sarajevo Main Railway Workshop, and others.

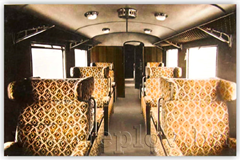

The main structural characteristics of passenger cars are that the underframe of the lower machine is made of steel, with a small wheelbase (two- and three-axle) and suspension with horizontal leaf springs. The car body is of wooden construction with a metal roof equipped with lanterns (ventilation exhausts). The car body lining was made of wood and covered with wooden veneers, with inserted glass or stone wool between them, and the interior walls and upholstery were padded with cloth felt for insulation against both extreme cold and heatwaves. During travel, since the cars were lightweight, they had a “stiff ride” and were not very comfortable for long journeys. All cars employed “Hardi” brake systems with compressed air. This type of braking was used exclusively on narrow gauge railways, except during the introduction of diesel railcars (DMV 801 and 802), where the “Božić” brake was in use.

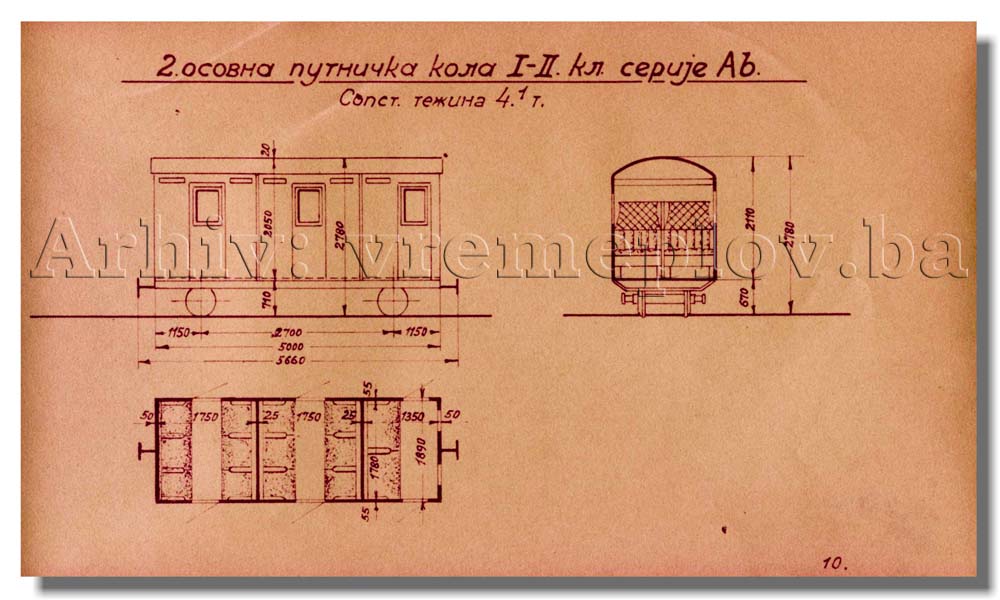

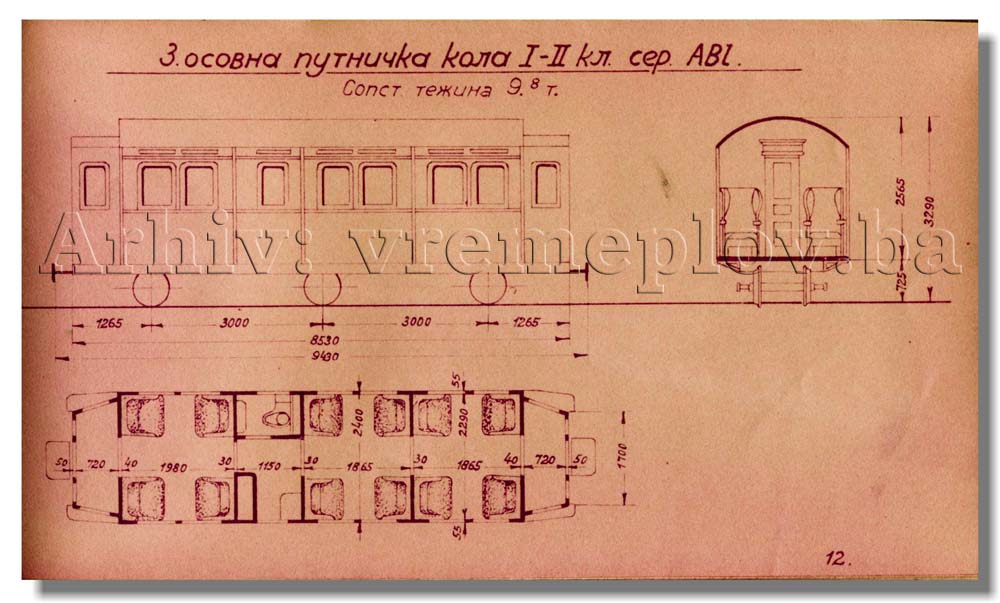

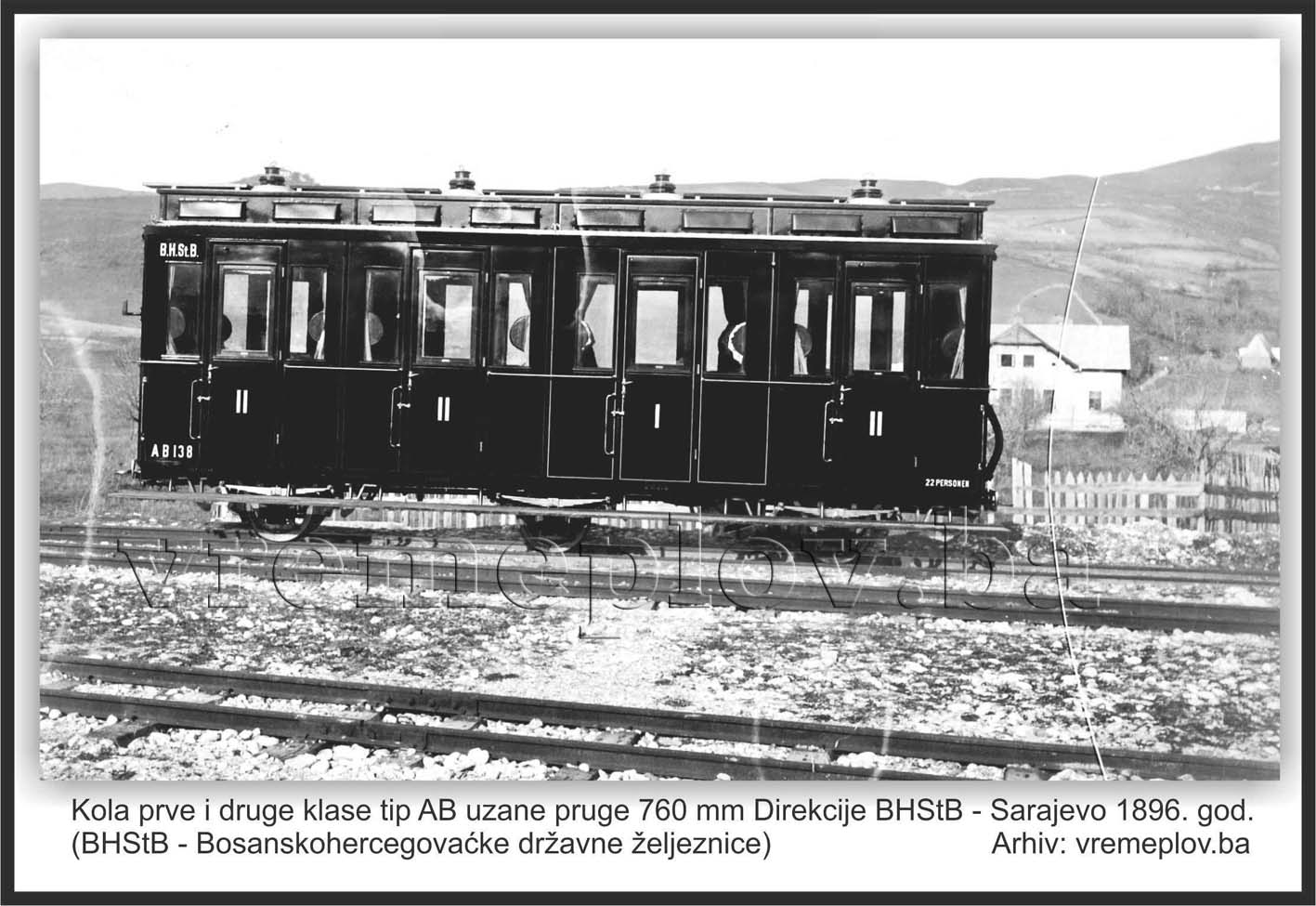

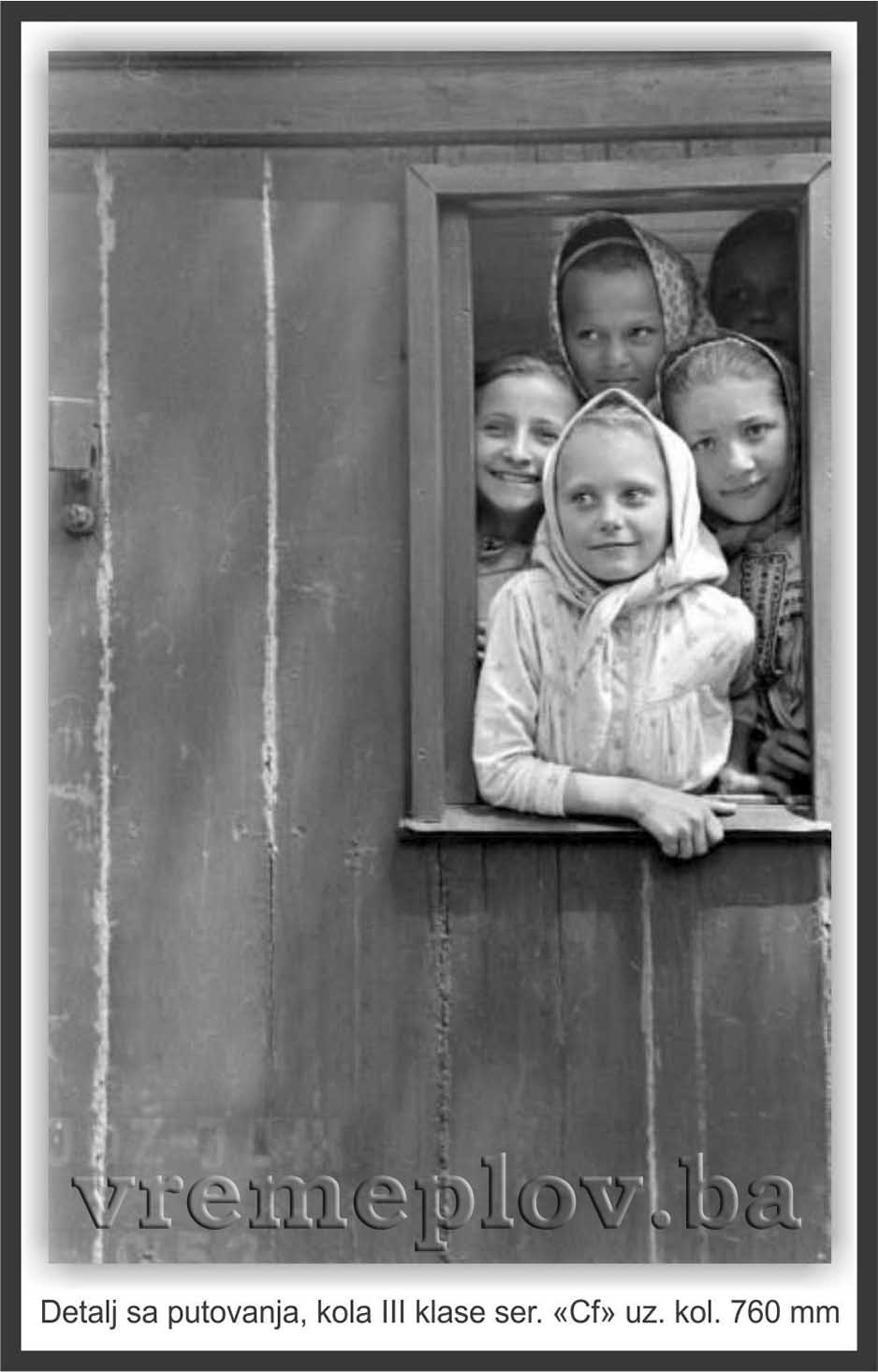

The types of passenger cars were: two-axle cars of the I and II classes, series “AB,” subseries “o” (subseries “o” means cars with entrances on the side walls of each compartment separately), with 4+12 seats. Three-axle cars of the III class, series “Co,” with 32 seats. Two-axle cars of the IV class, series “E,” subseries “k” (subseries “k” means cars with benches for sitting and a fare was charged for the third class), with 20 seats. If the cars did not have benches for sitting, the fare was for the fourth class, and seats were “wherever you want and how you want.” The main feature of the design of these cars is that they were of an “enclosed type,” as each compartment on the left and right side had entrance doors. First-class cars (with 4 seats in a compartment) and second-class cars (with 6 seats in a compartment) had soft seats and upholstered backs with fabric. Third-class cars (with 8 seats in a compartment) had seats and backs made of connected wooden slats and lacquered with clear varnish. Fourth-class cars (two compartments with 10 seats each) had plain wooden benches.

Modernization of the Rolling Stock

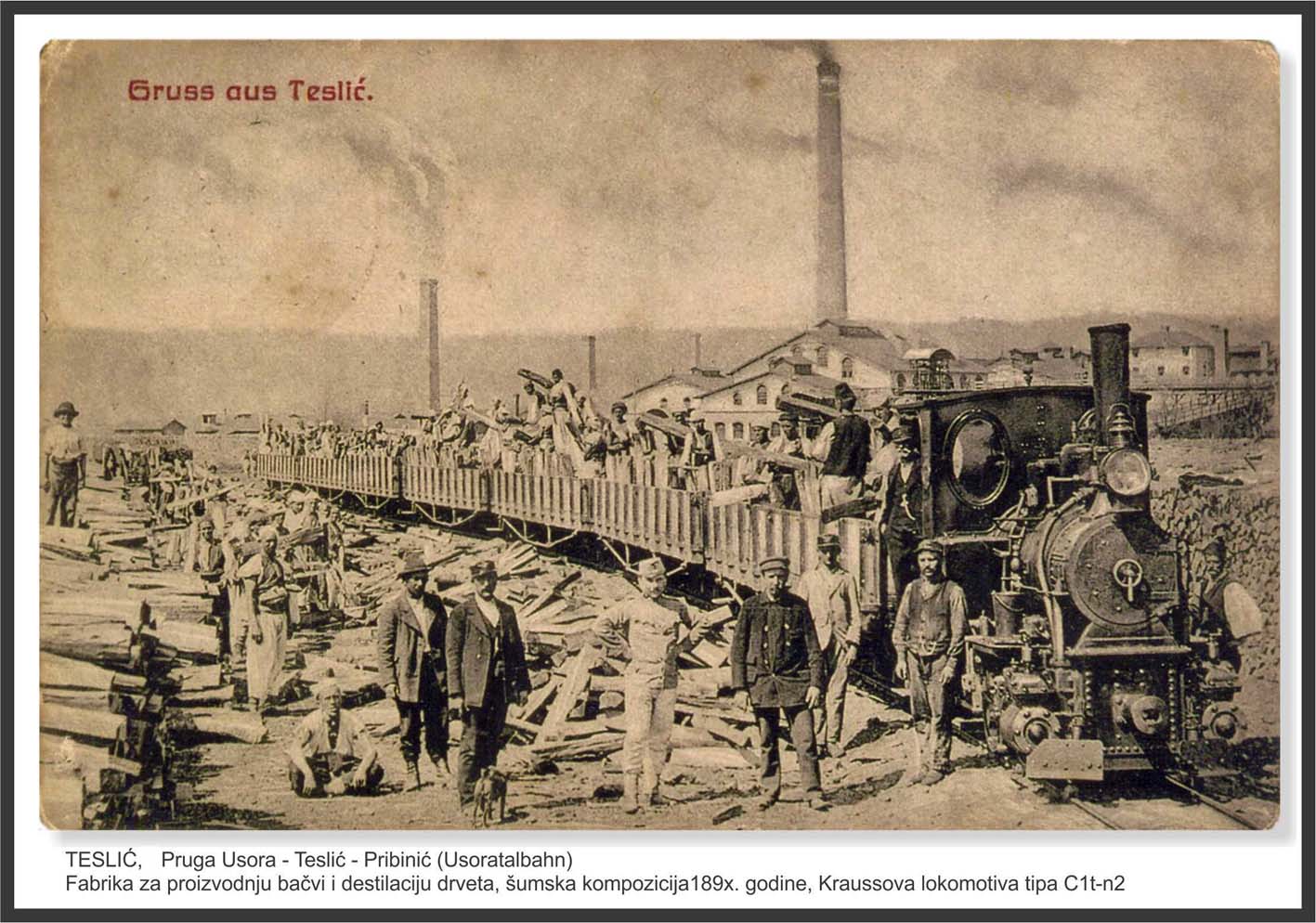

As time passed, Bosnian railways served as an excellent experiment for foreign manufacturers of passenger cars, helping to improve the quality of future designs both in the underframe of the lower machine and the bogie frame, as well as in the enhancement of the train equipment quality. At that time, Austria had a considerable length of narrow gauge track primarily used in local mountain line traffic (tourist lines), then in Italy, Switzerland, and some in Croatia and Serbia. By the outbreak of World War I, the length of railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina was an impressive 1,684 km of narrow gauge and 124 km of standard gauge railways. These 1,684 kilometers of narrow gauge railways were under state management and control, not counting about 1,000 kilometers of constructed logging, mining, and industrial tracks owned privately, on which passenger traffic was mostly organized. It can be freely stated as a conclusion that the built and well-developed network of narrow gauge lines in BiH, by European standards, served as a model for narrow gauge railways and was well-covered in the technical literature of that era.

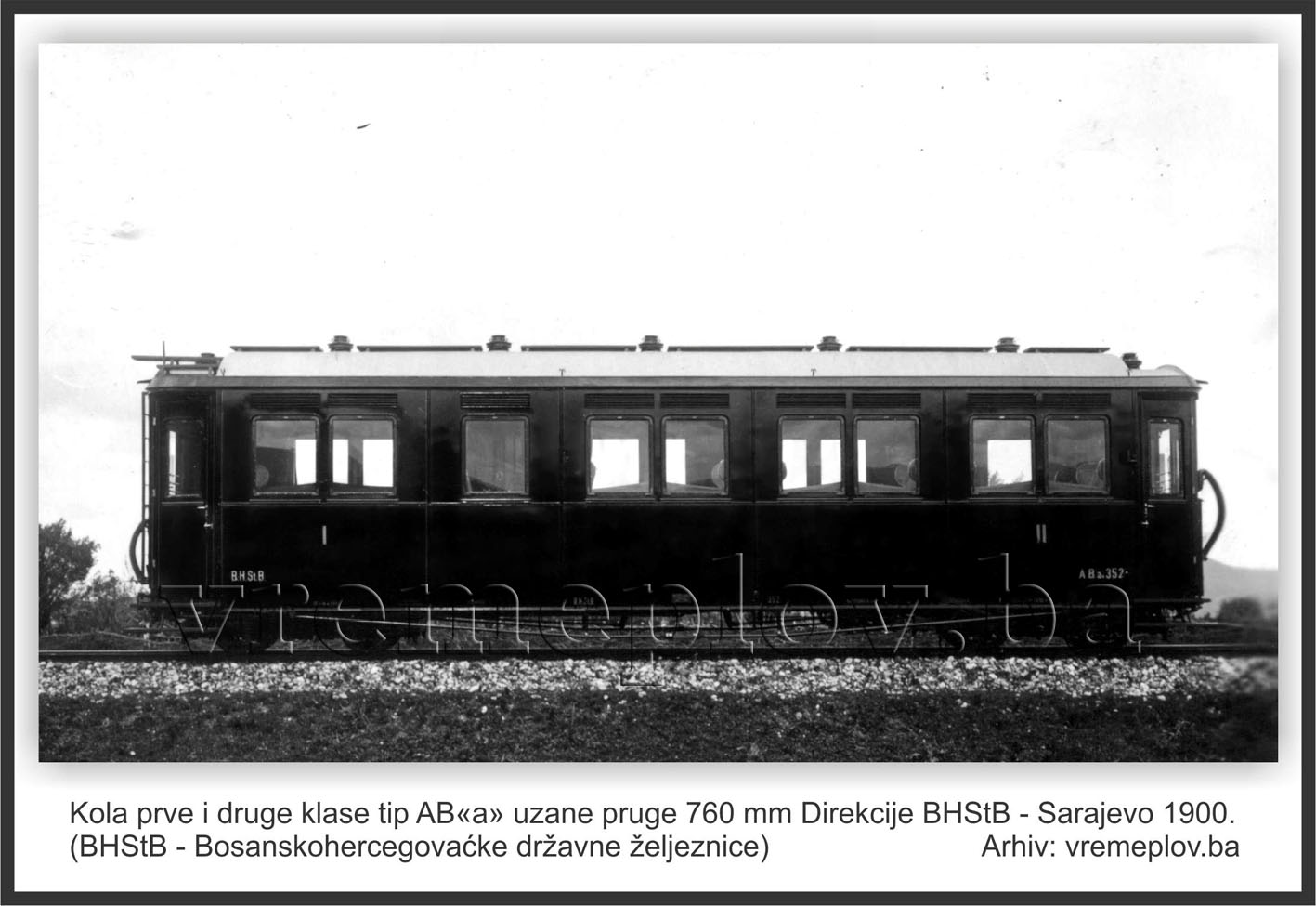

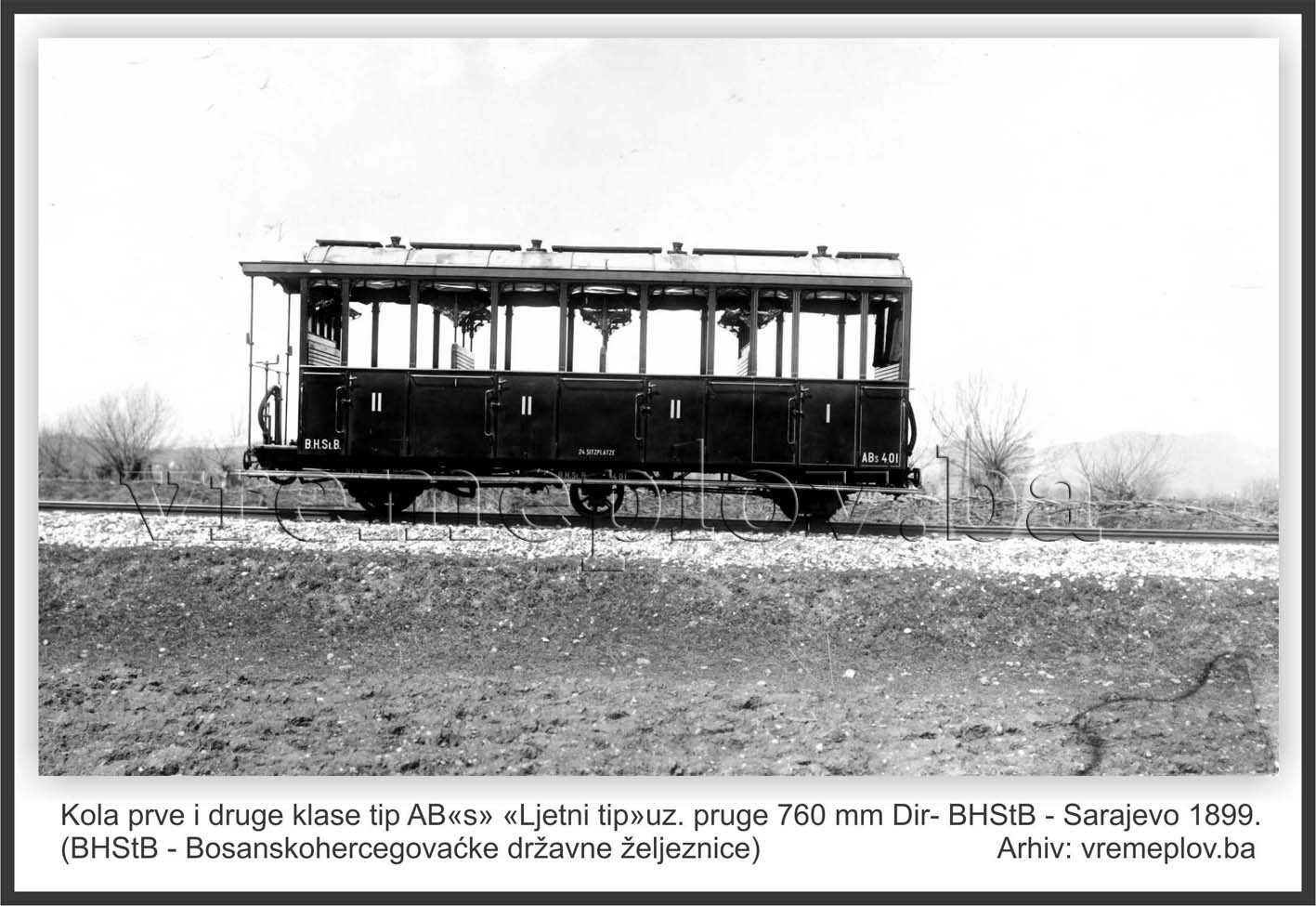

Since 1895 to 1910, new and more modern carriages for passenger and freight transport were purchased on narrow gauge lines. Essentially, the design of the passenger cars remained the same, that is, a wooden structure of the carriage body and gas lighting. The only improvement was in the way the steel underframe was suspended, which made the cars run more smoothly, and the arrangement of the first, second, and third class compartments was more suitable for handling passengers with richer amenities in terms of seating, thus providing more comfortable rides.

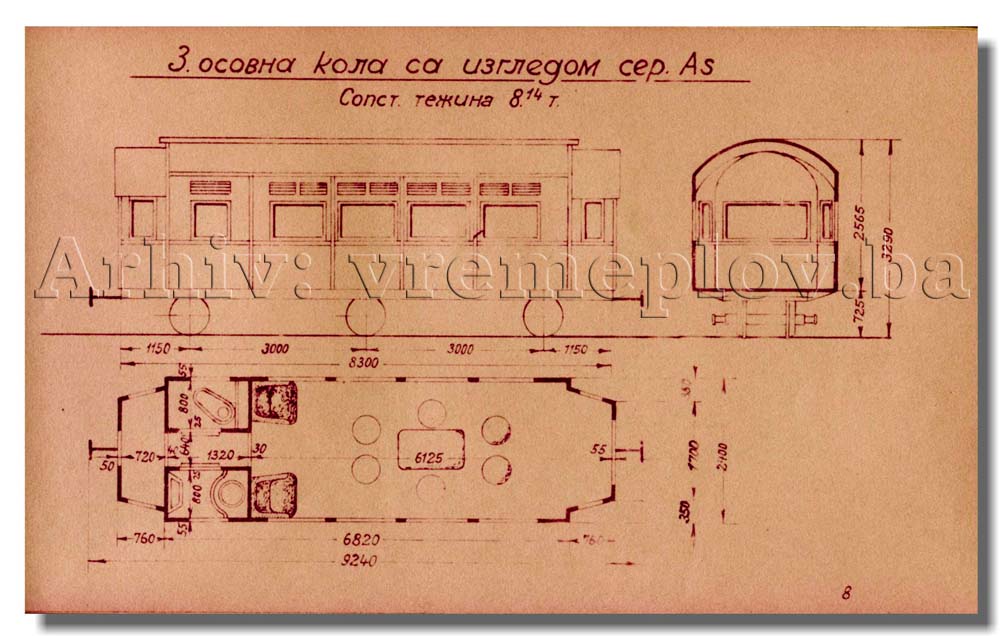

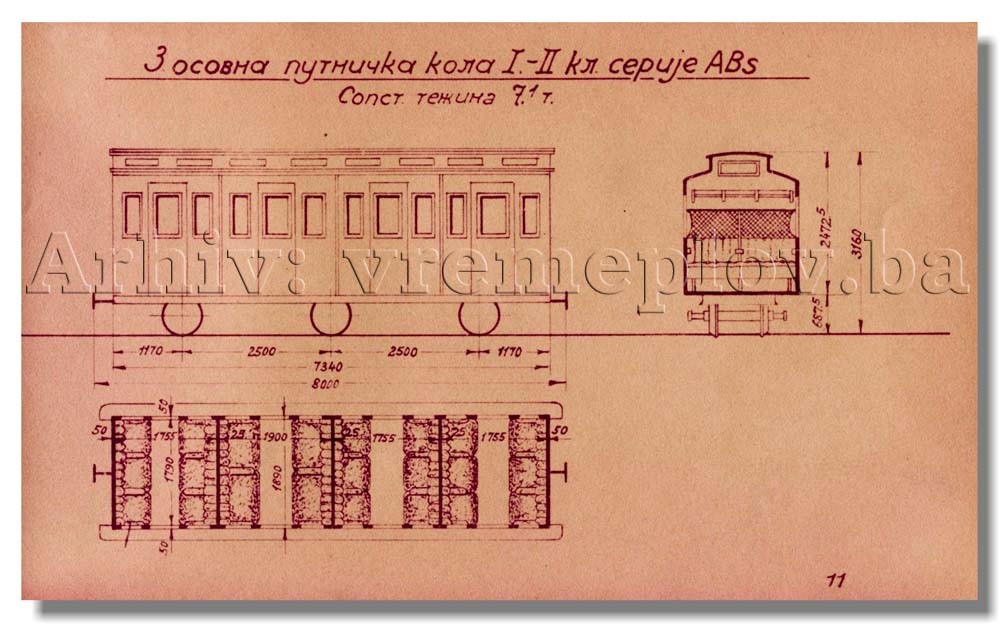

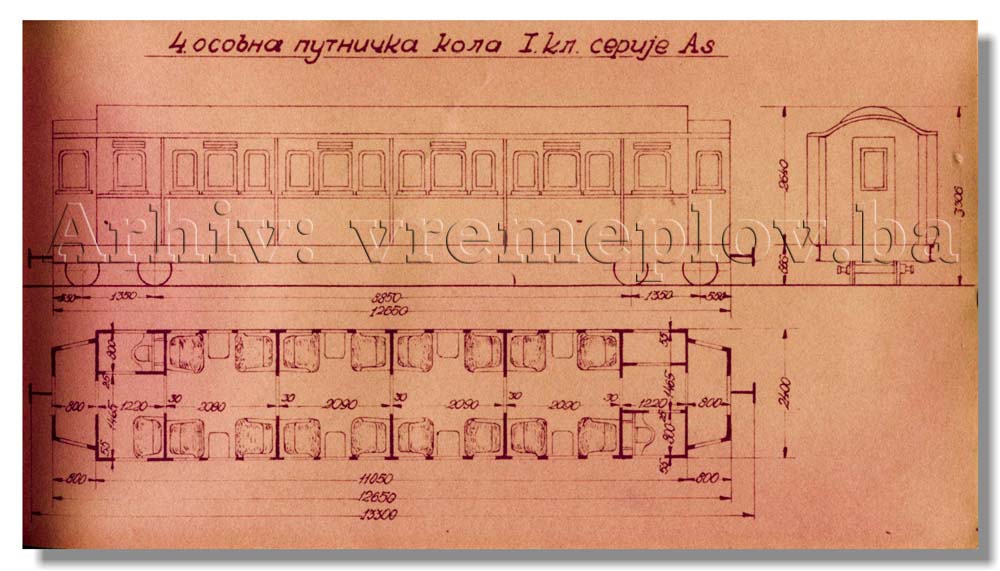

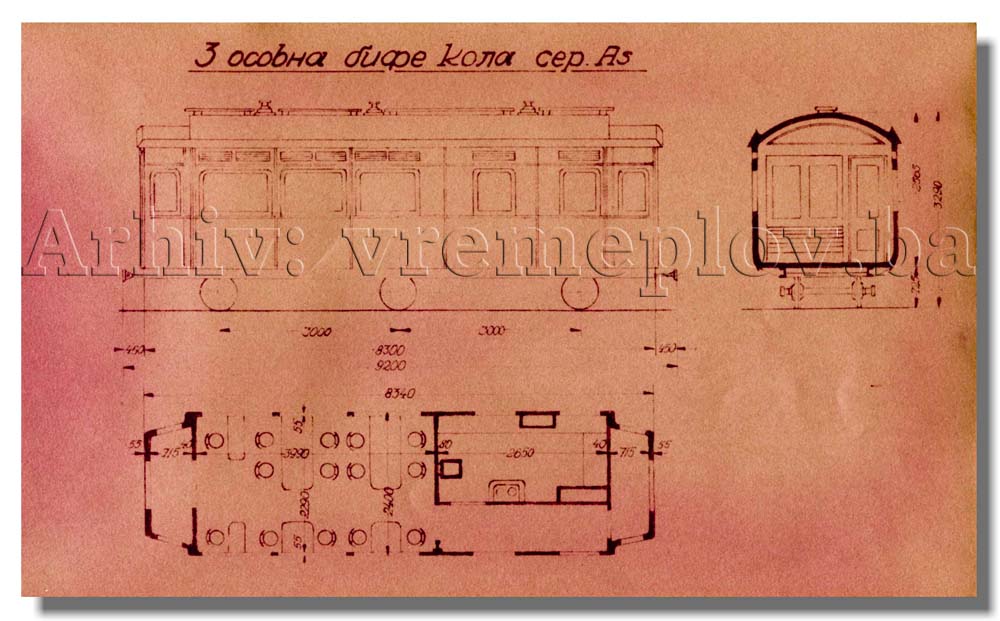

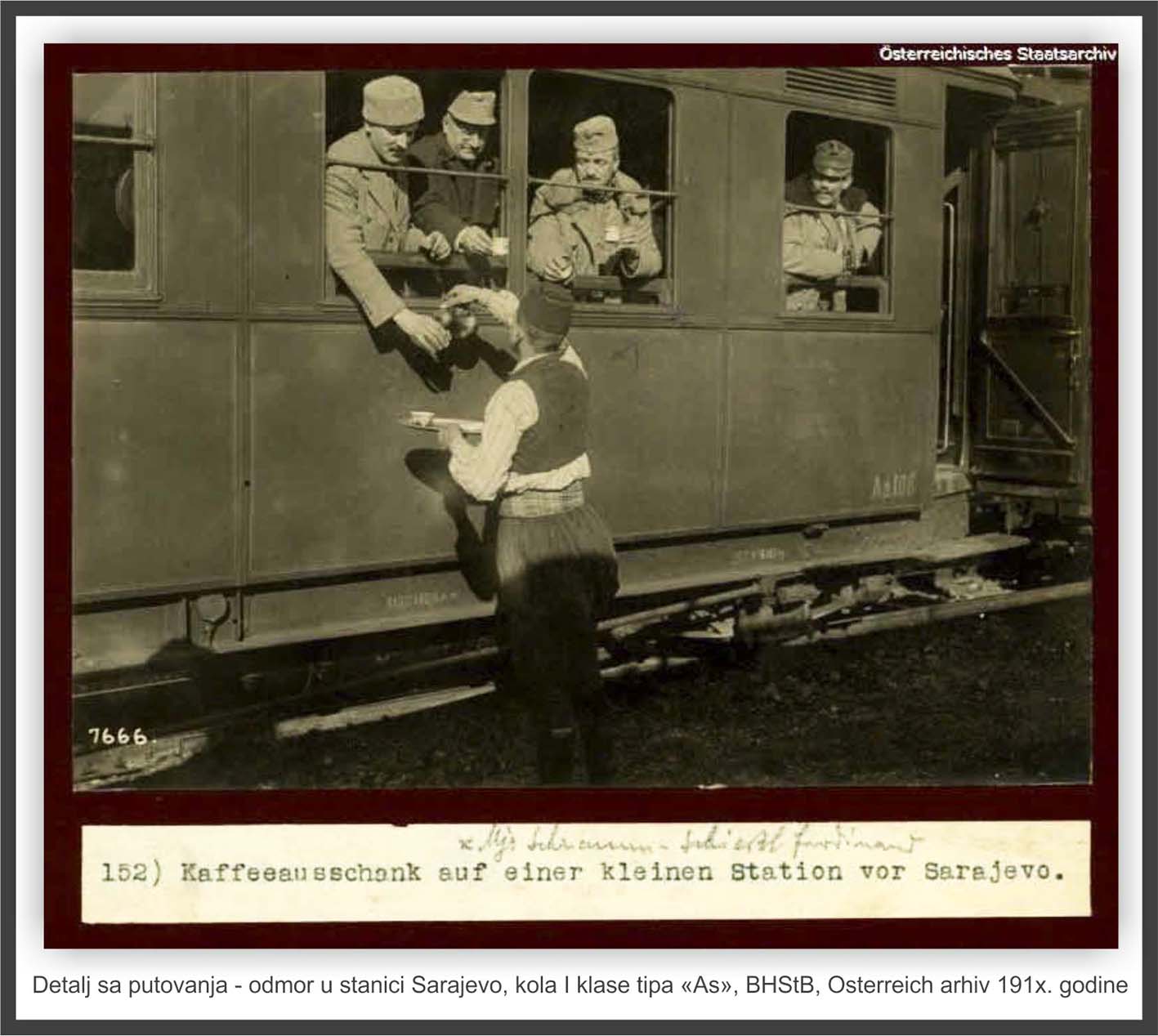

Types of passenger cars were: Two-axle cars of the first and second class, series “AB,” subseries “s” (subseries “s” are cars with a corridor in the middle of the car), with seating capacities ranging from 22 (4+18) to 24. Fourth-axle cars of the first class, series “As,” with 16 seats, and fourth-axle cars of classes I and II, series “ABs,” with 16 (4+12) seats. The main feature of the design of these cars is that the passenger entrances were at the ends of the car, the corridor ran through the middle, and they featured toilets and gas lighting. Additionally, the upper luggage compartment was “metalized,” while the interior was made of wood.

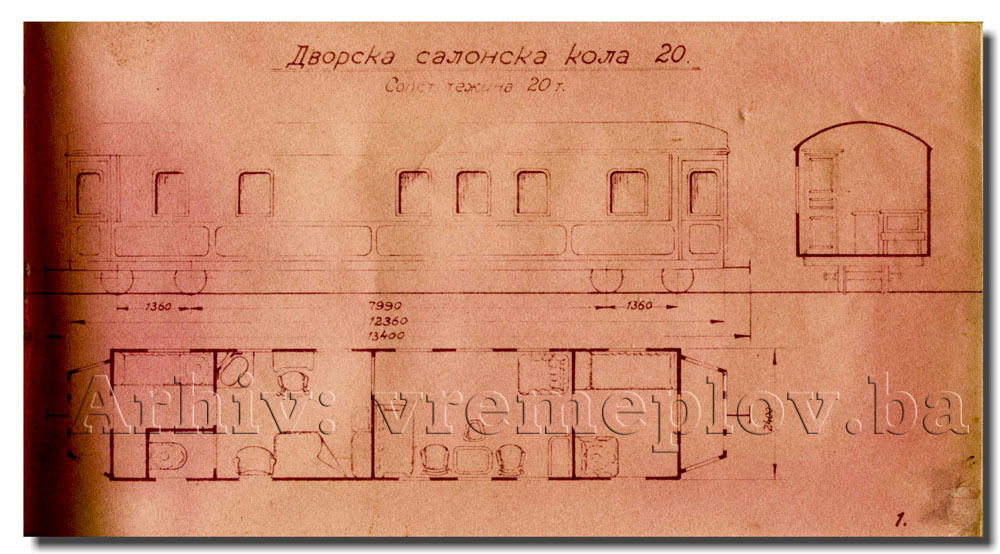

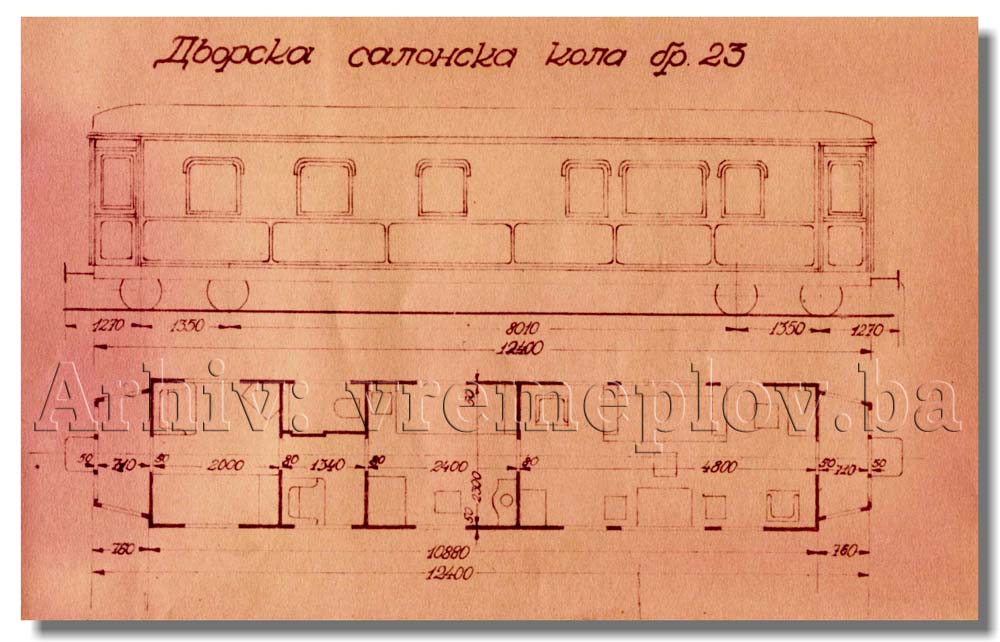

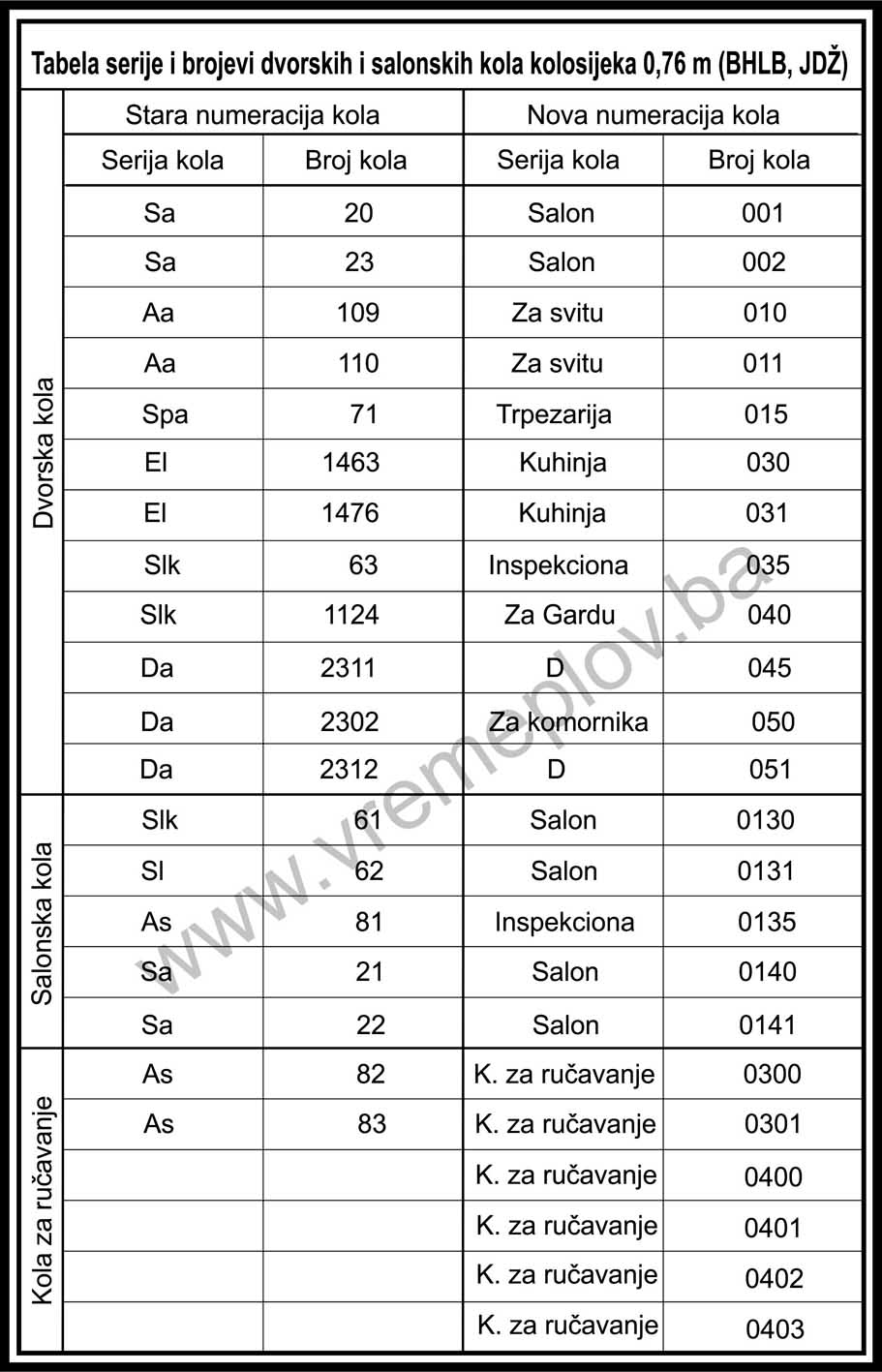

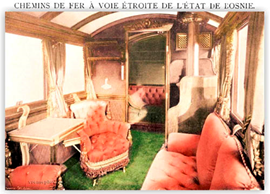

We must mention that during the Austro-Hungarian administration in Bosnia and Herzegovina, there was a special train for high guests, consisting of several court and salon carriages. The composition of these carriages was designated for special occasions, such as the travel of the emperor himself (e.g., during Emperor Franz Joseph’s visit to Sarajevo and Mostar from May to June 1910) or, depending on the need and the condition of the wagons (combined), it was incorporated into passenger trains that transported high-ranking guests of the royal family and important officials from both civil and military authorities. There is an article about the royal train composition that we published earlier, which you can read using the link: https://vremeplov.ba/2025/?p=15241 and a link about the operation of Royal trains https://vremeplov.ba/2025/?p=17356

Between the Two World Wars

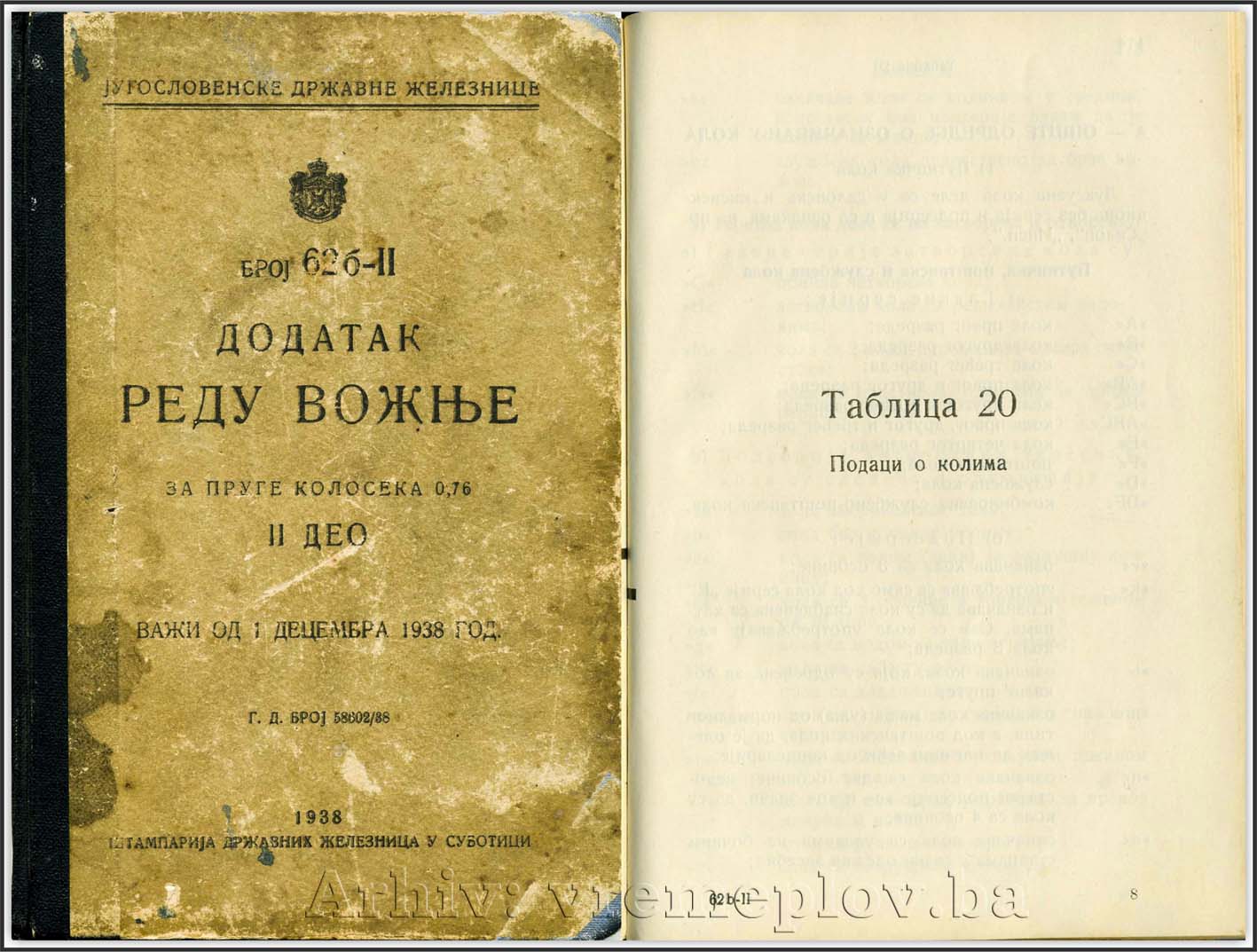

After the end of World War I and the creation of the State Union of Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia (SHS) and later Yugoslavia, the railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina came under a unified ownership mark, specifically the State Railways of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (SHS-SHC) or the Yugoslav State Railways (JŽ). The main directorate was located in Belgrade, and the “Regional” directorate for BiH was in Sarajevo. The track park inherited from the former regime was used in its current condition, and it can be said that this condition was catastrophic. Namely, the repair and maintenance alone took considerable time due to the state of spare parts, and procurement from foreign factories (due to the dissolution of Austria-Hungary and the German Empire and the formation of new states) was complicated by foreign exchange dealings, as workshops (and even factories) did not have “foreign currency accounts,” except for government sectors involved in trade and similar activities.

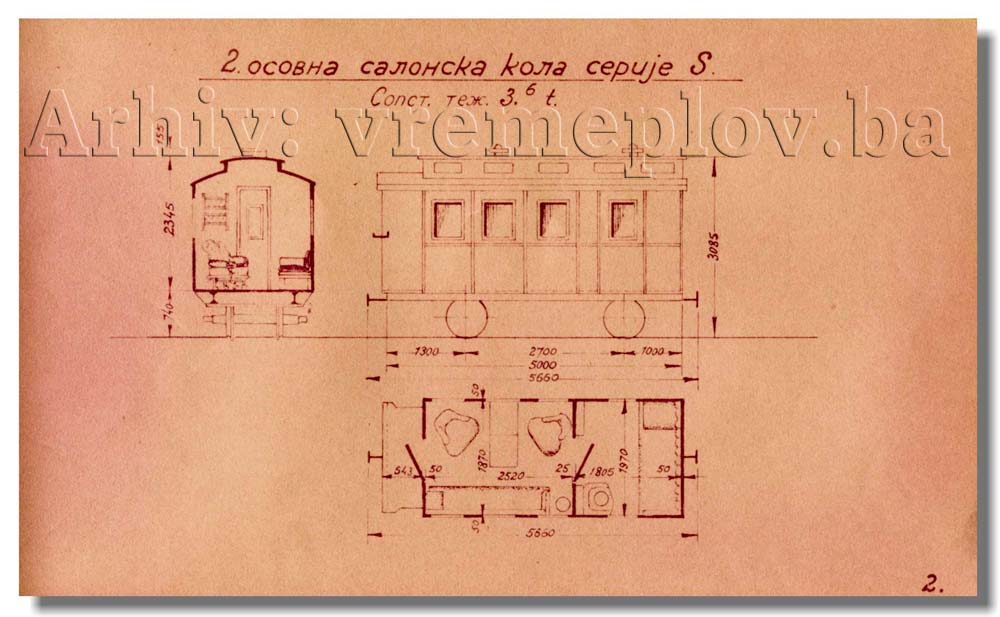

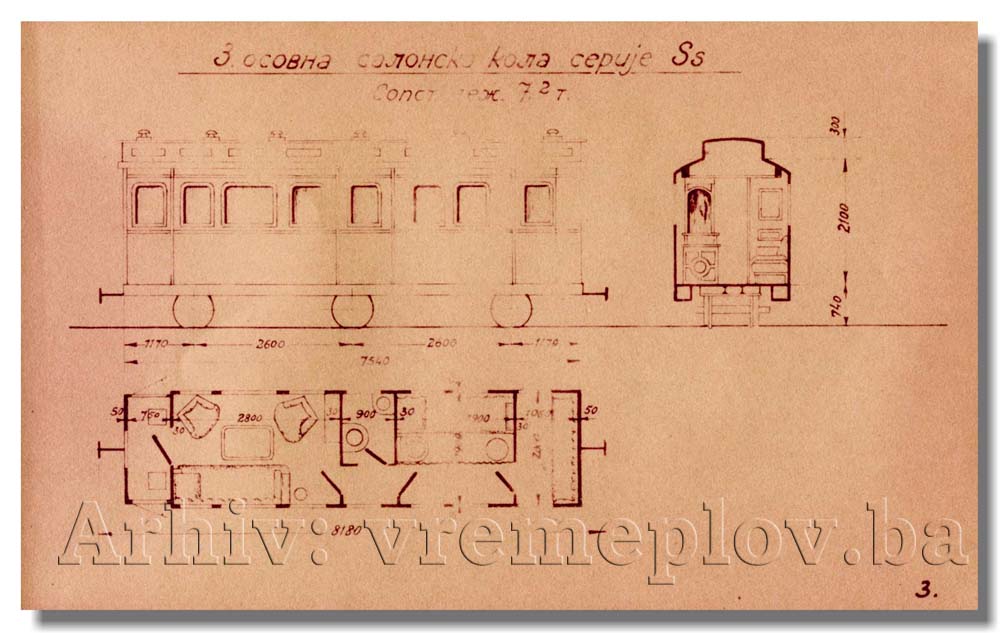

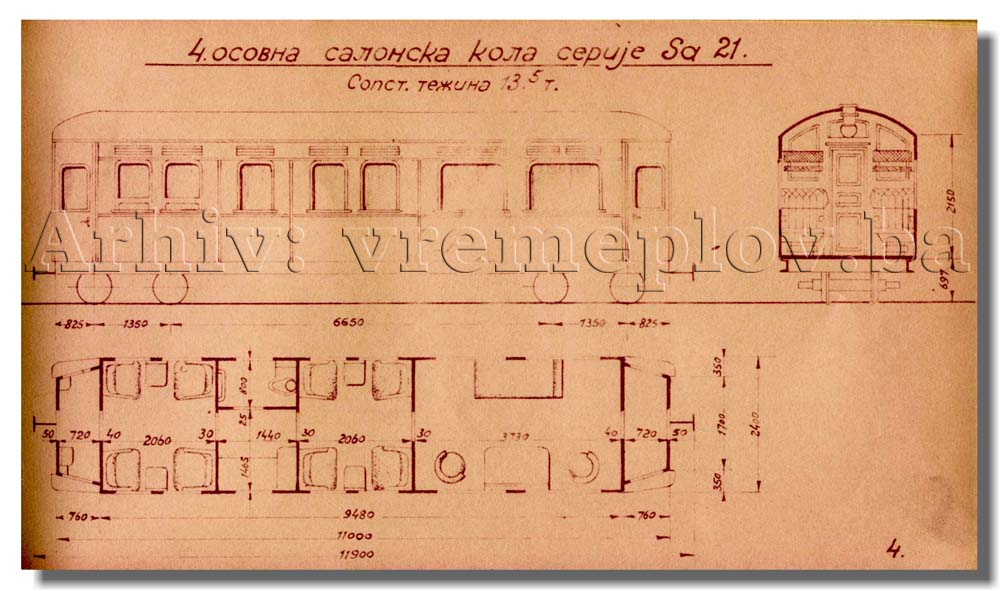

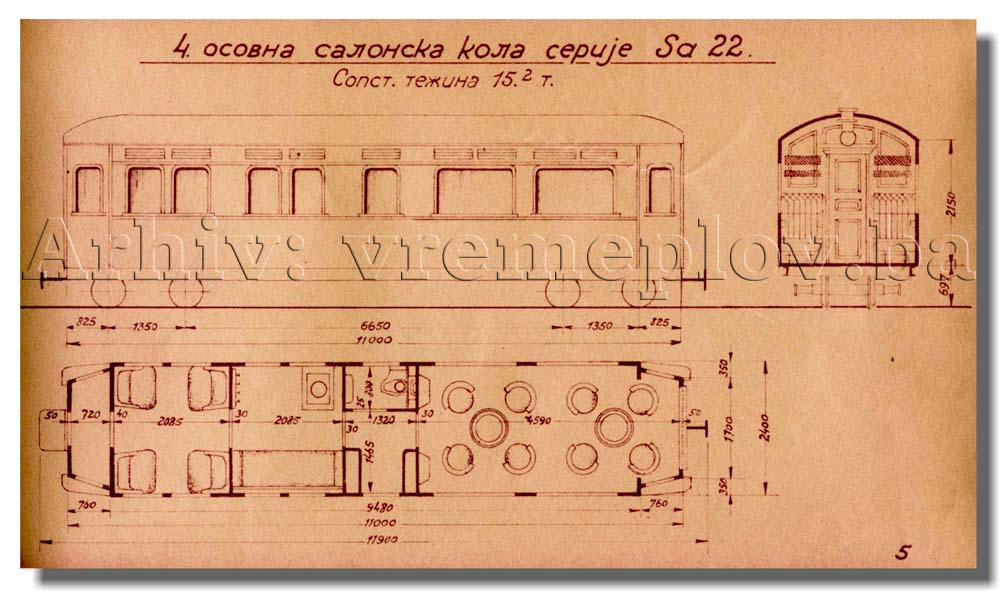

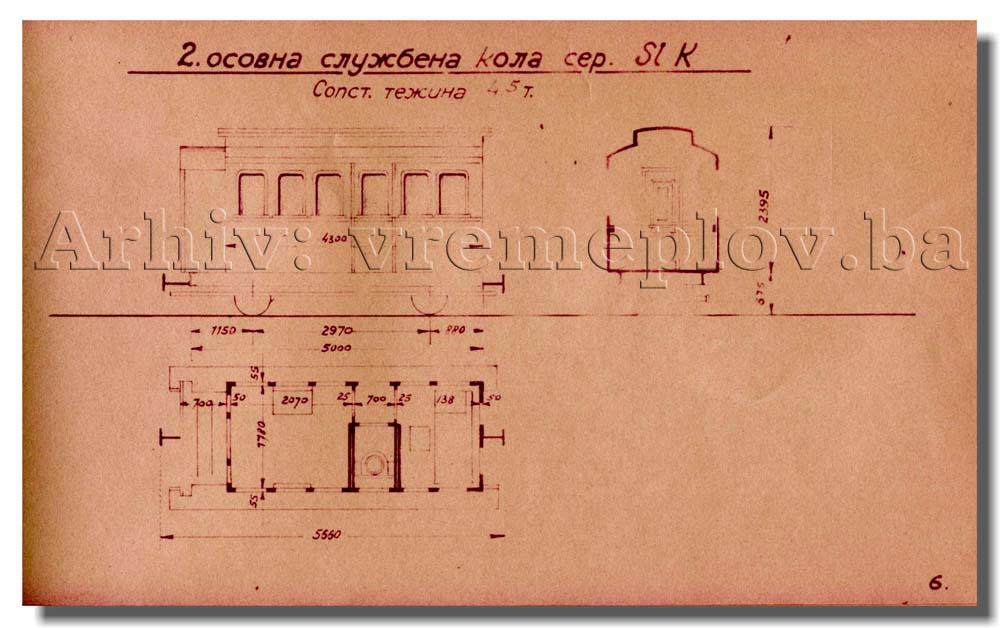

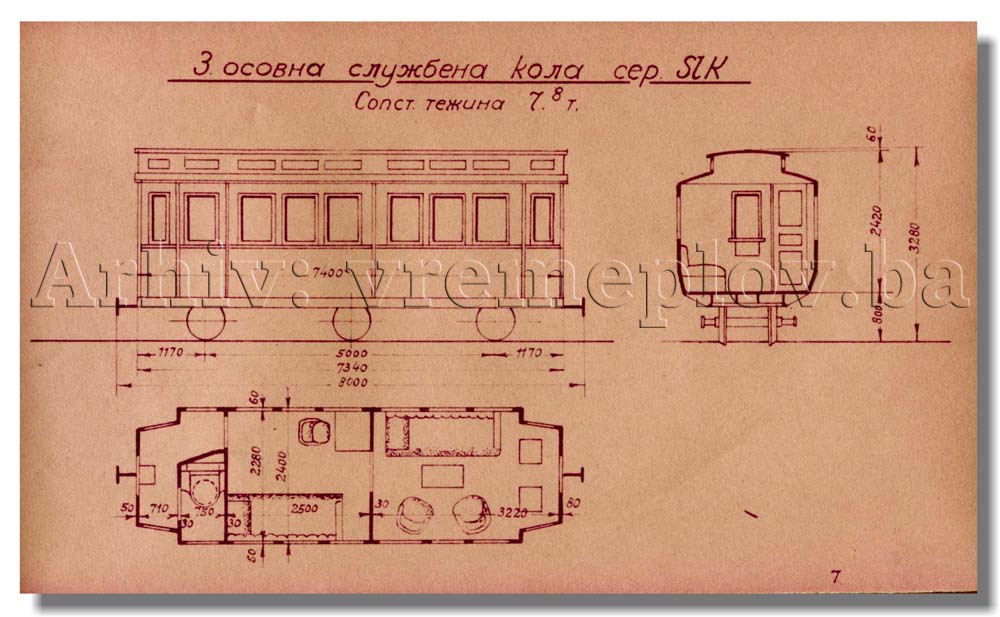

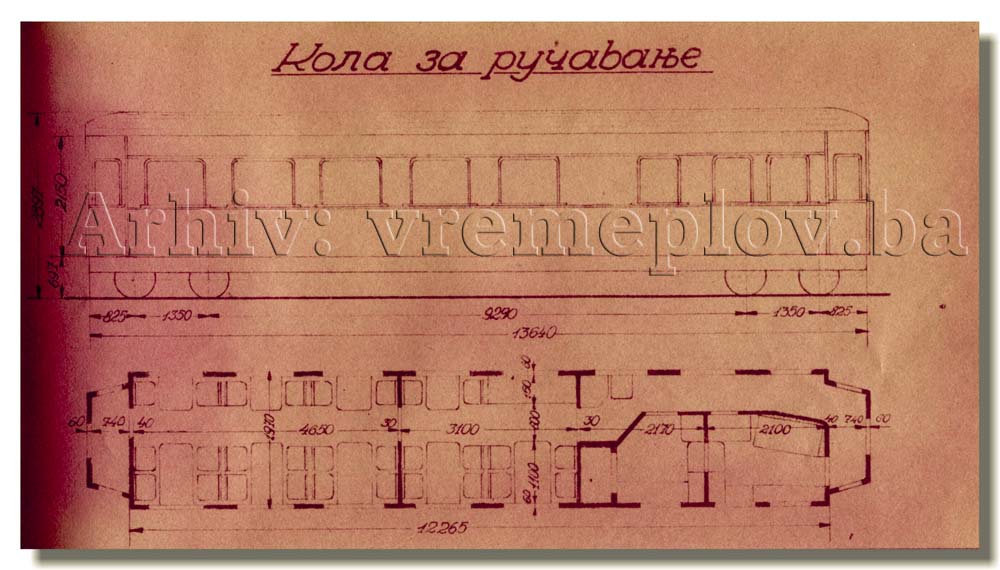

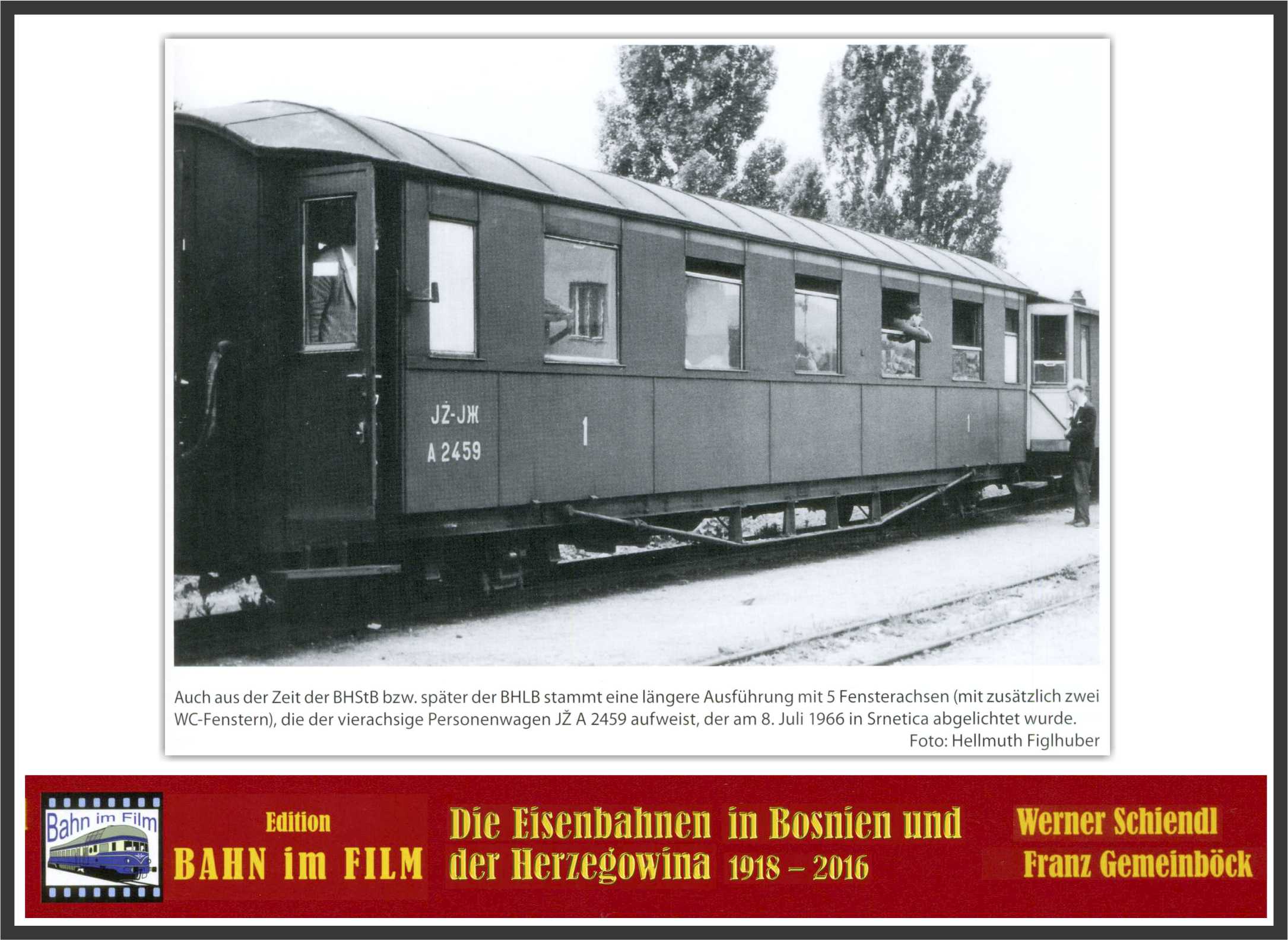

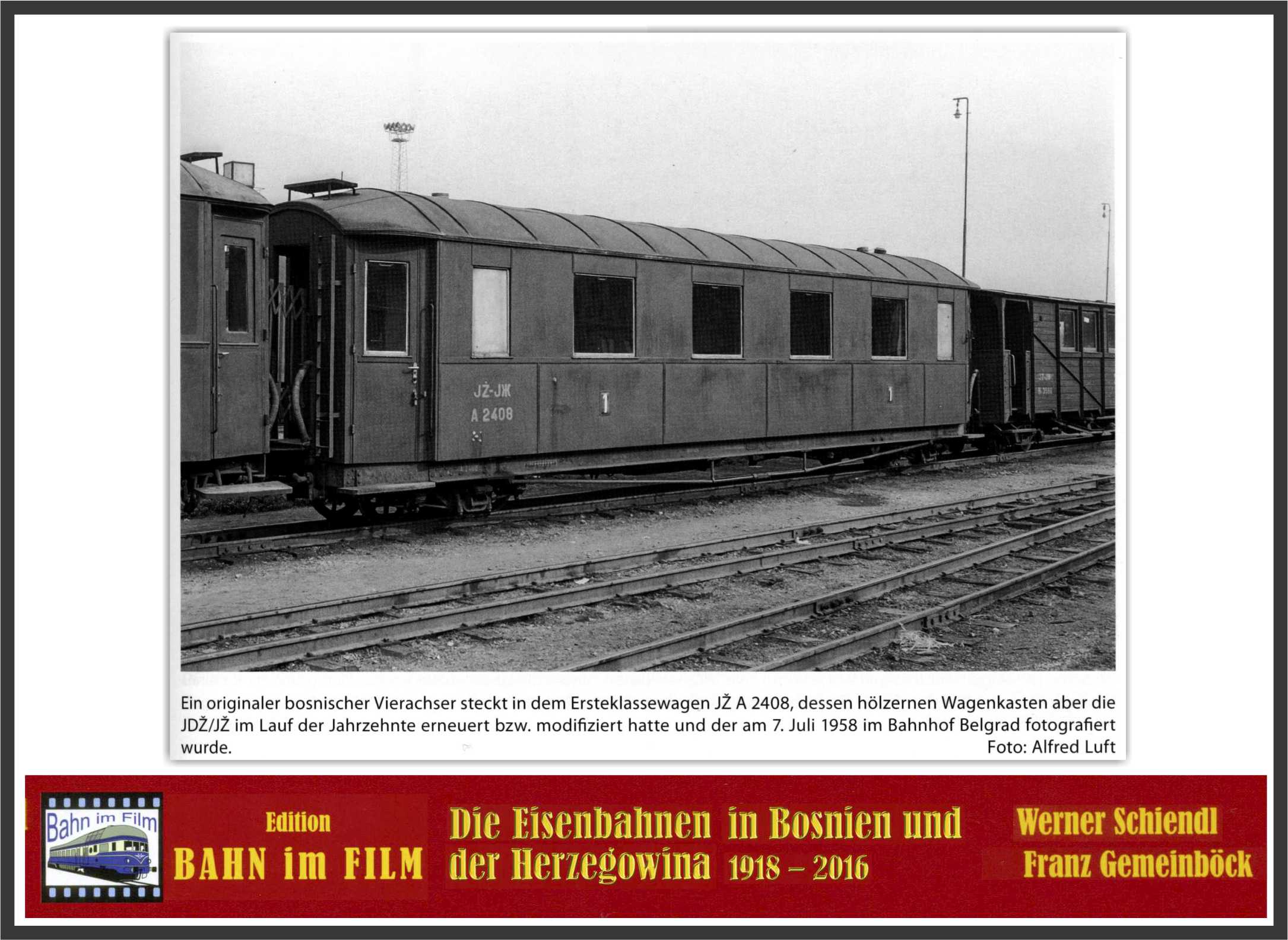

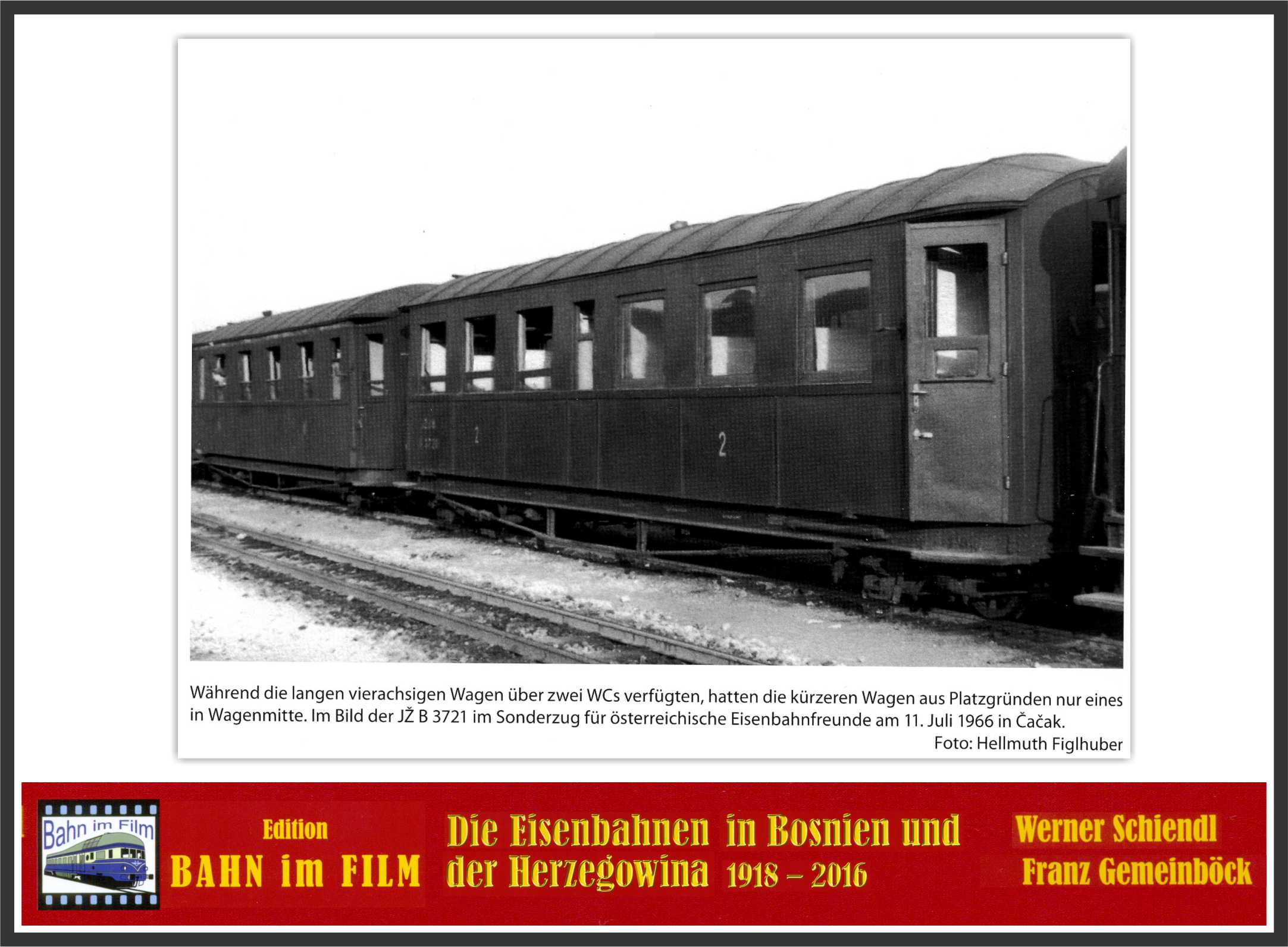

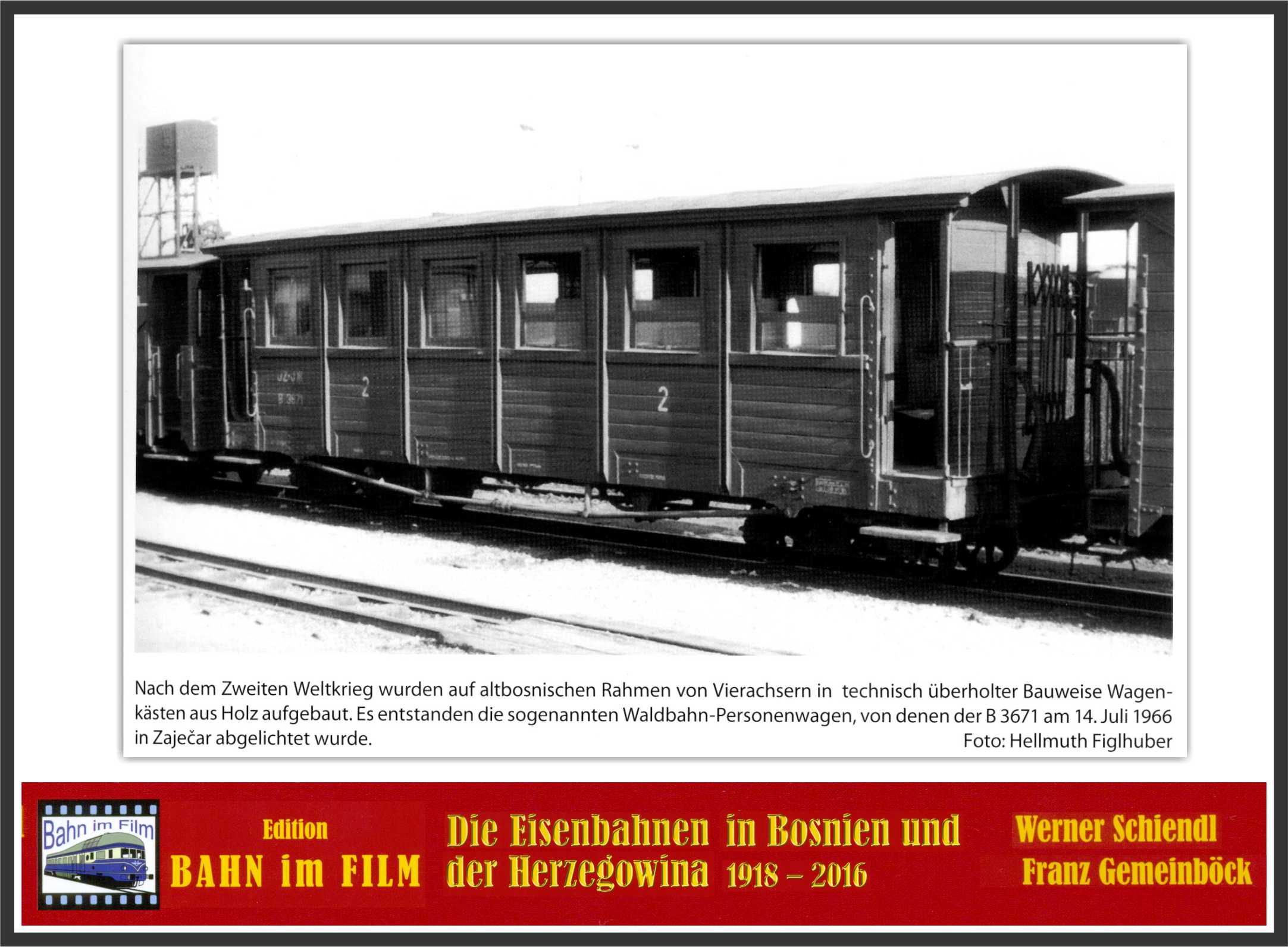

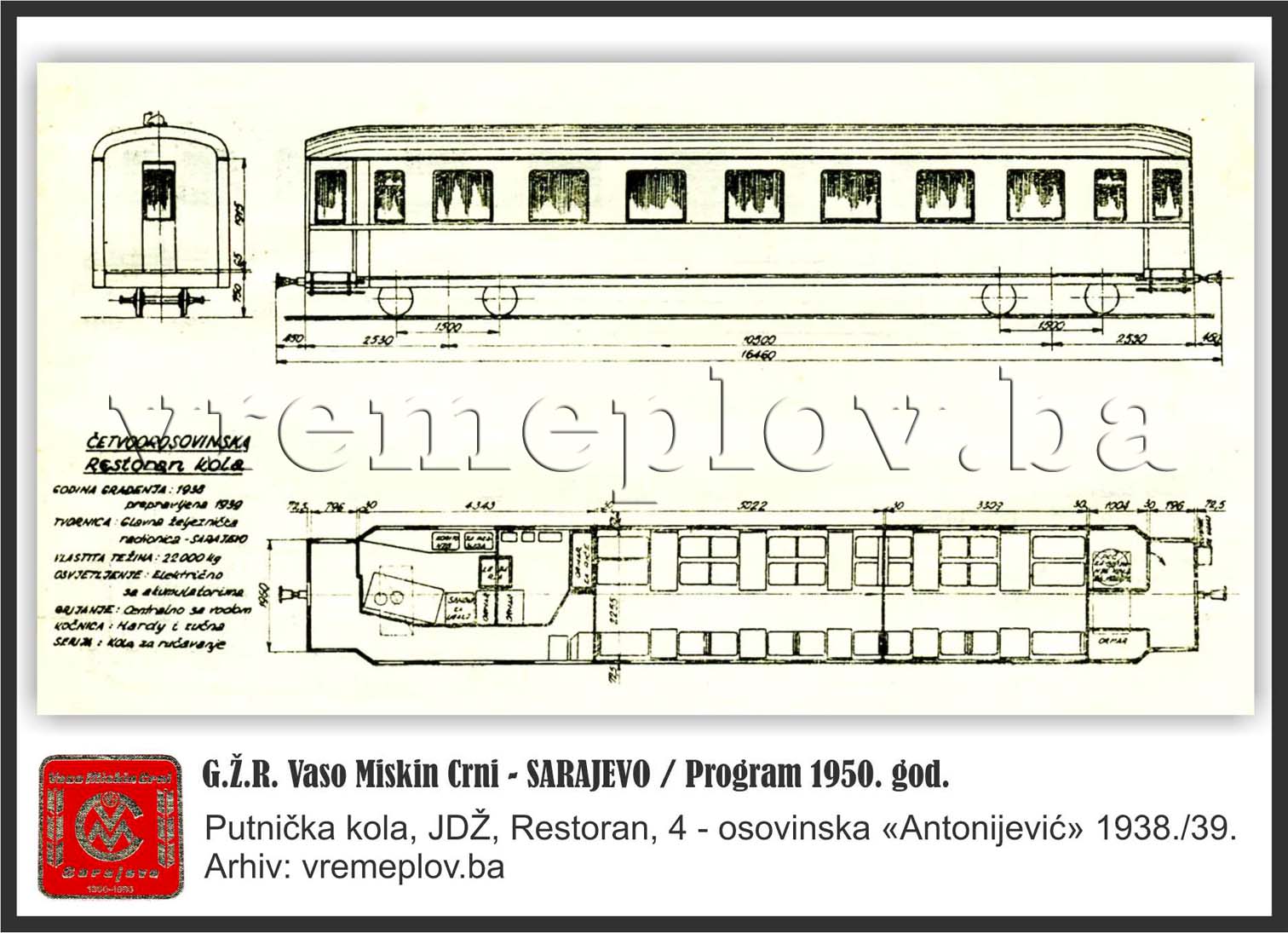

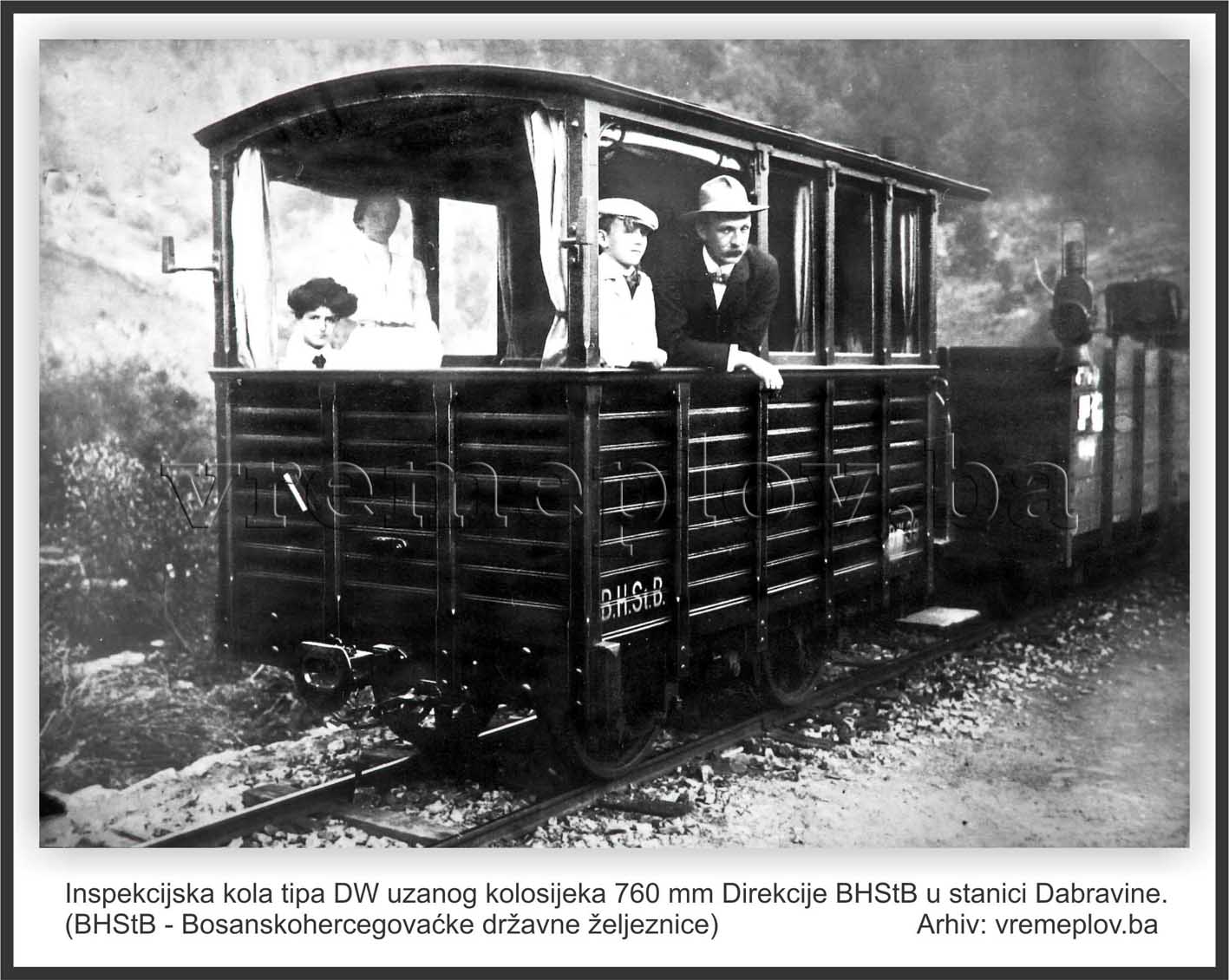

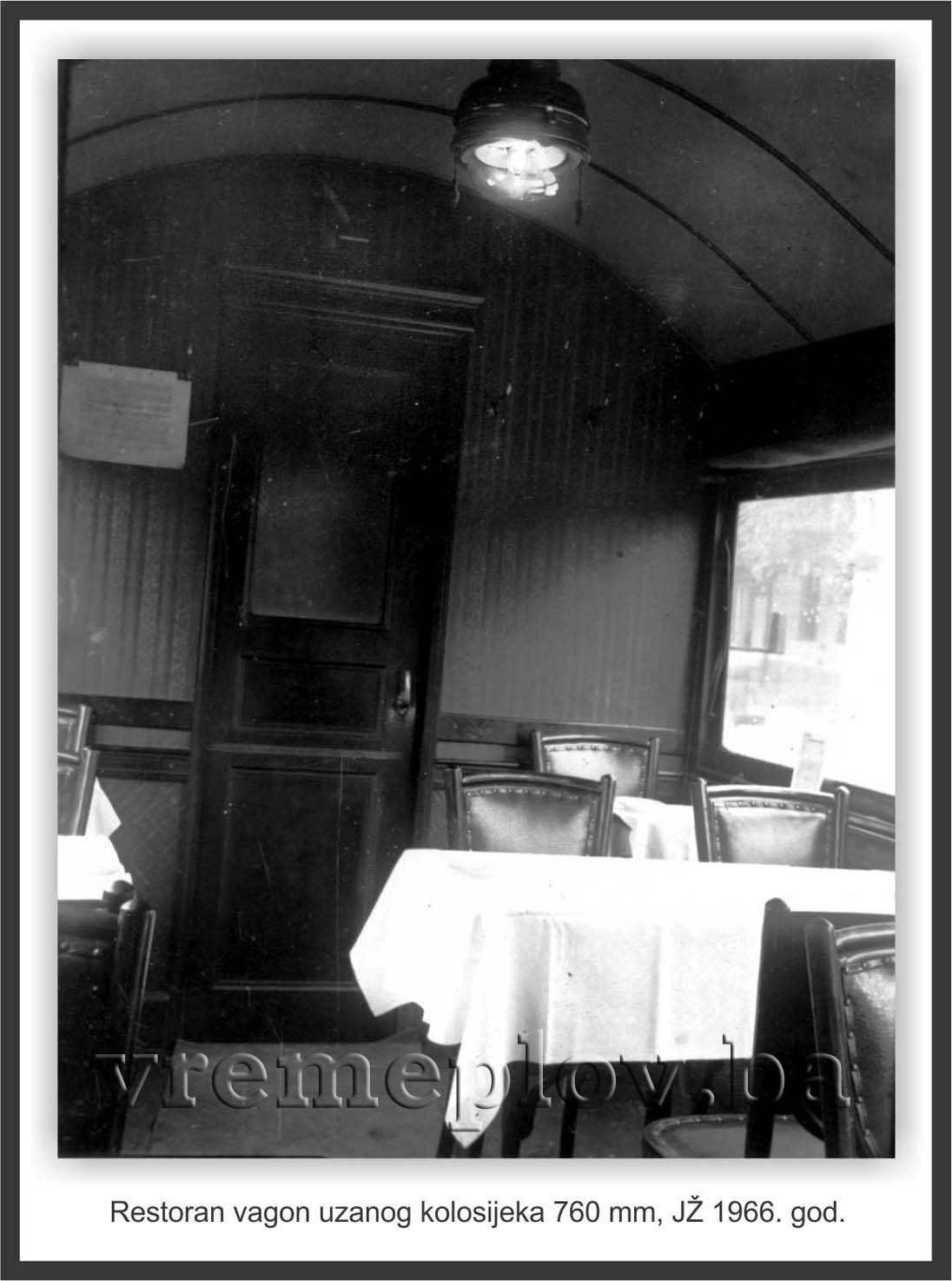

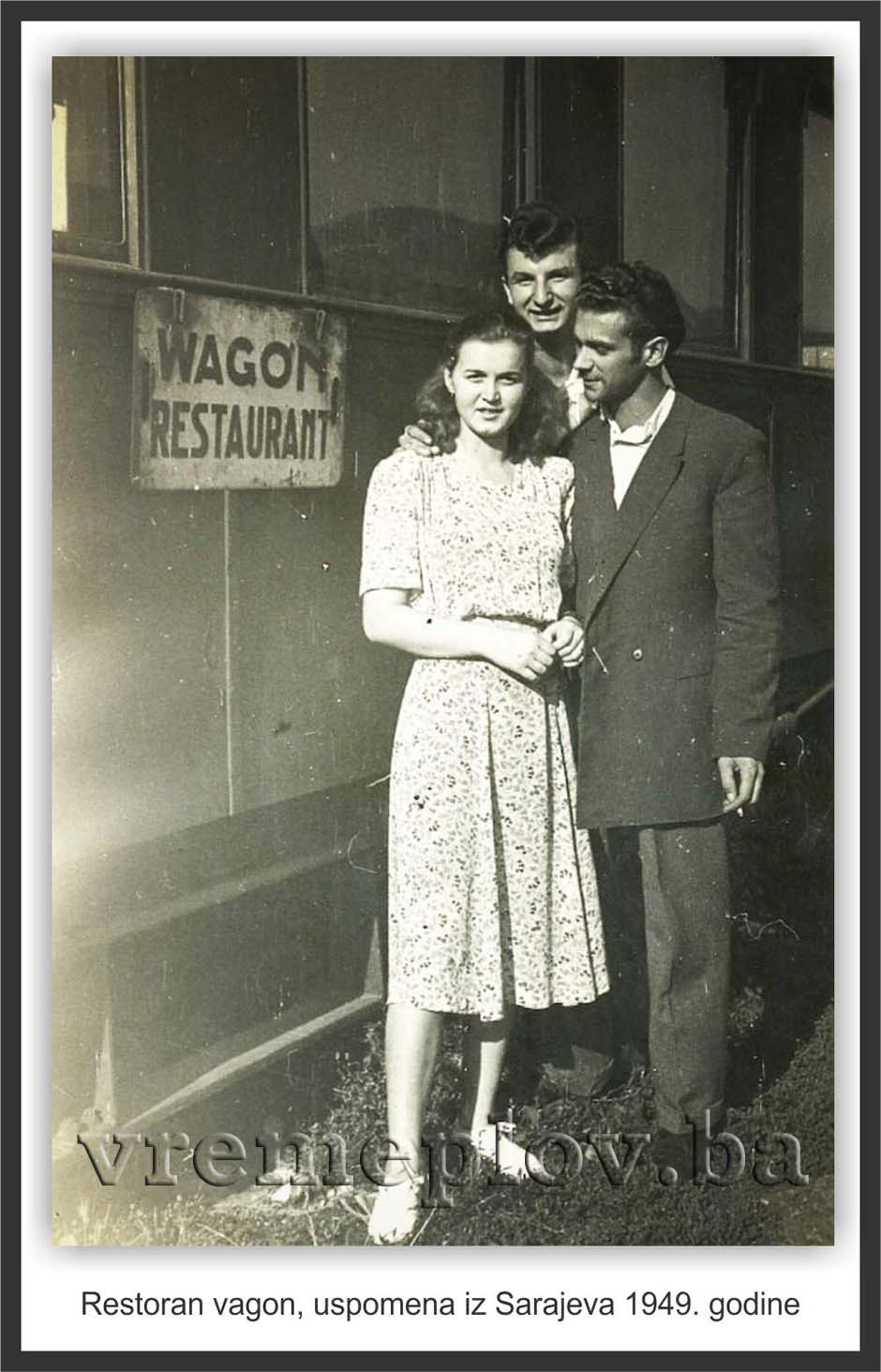

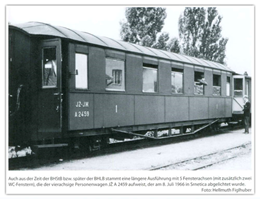

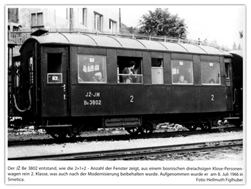

Due to the narrow gauge in Bosnia and Herzegovina being a significant part of reparations (compensation for damages caused by the war), passenger cars of greater lengths were supplied, but with an old flaw in the wooden construction of the wagon’s frame. These cars (13.7 meters long) were of Class II with 36 seats and Class III with 48 seats, and a “Diamond” turntable (four-axle) chassis with a stiff ride. This type of car, later converted by the Sarajevo railway workshop into special cars, included dining cars, inspection travel cars, and “salon” cars for sleeping and the like. The types of modified cars (album of cars, width 0.76 meters) can be viewed in the attached gallery of this article.

During the time of the Versailles Yugoslavia, there were four wagon factories: the Wagon Factory in Slavonski Brod, the “Jasenica” wagon factory in Palanka, the wagon factory in Kruševac, and the wagon factory in Smederevo. These factories were backed by foreign capital and essentially served as assembly workshops where the wagons were assembled.

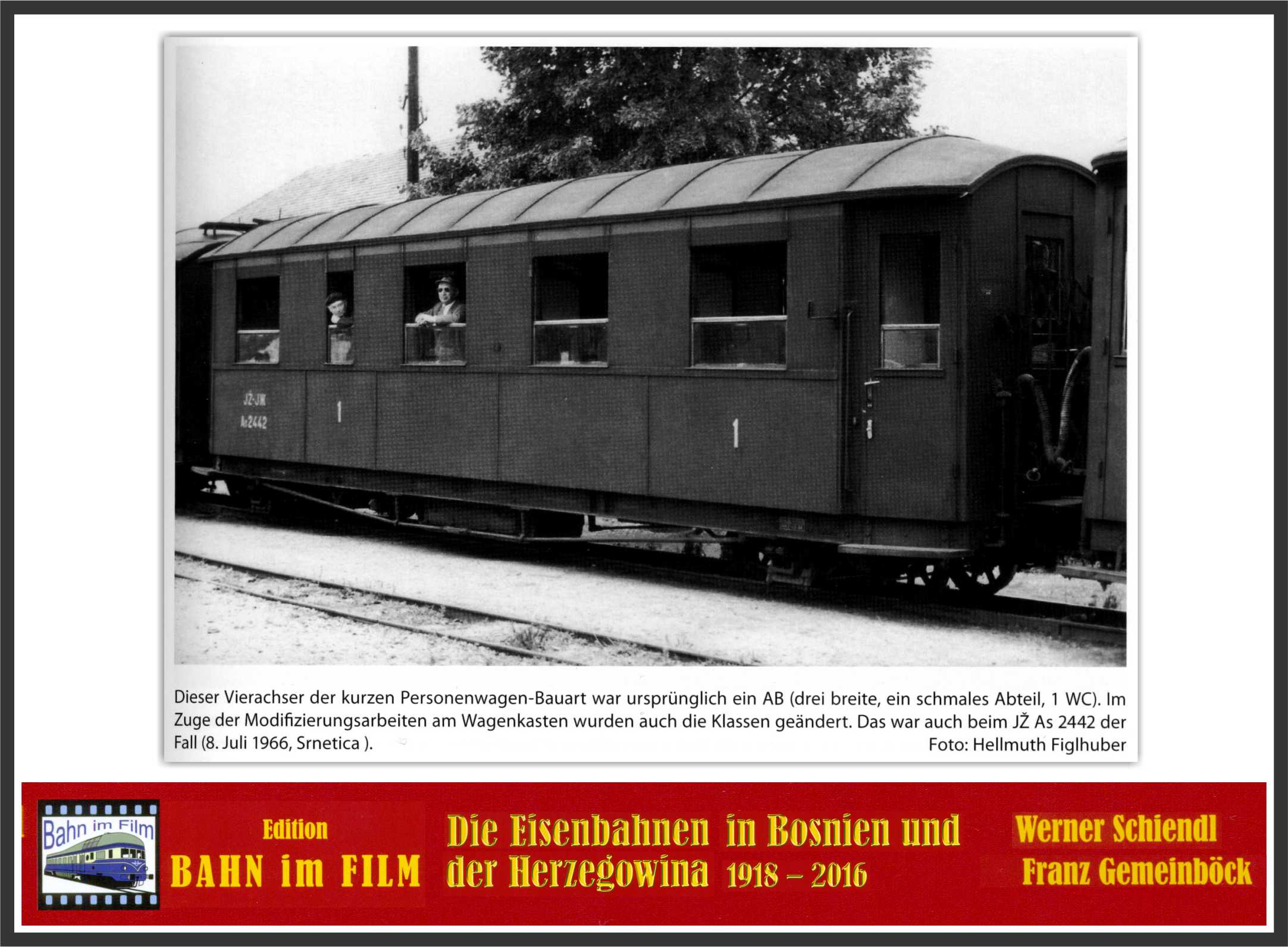

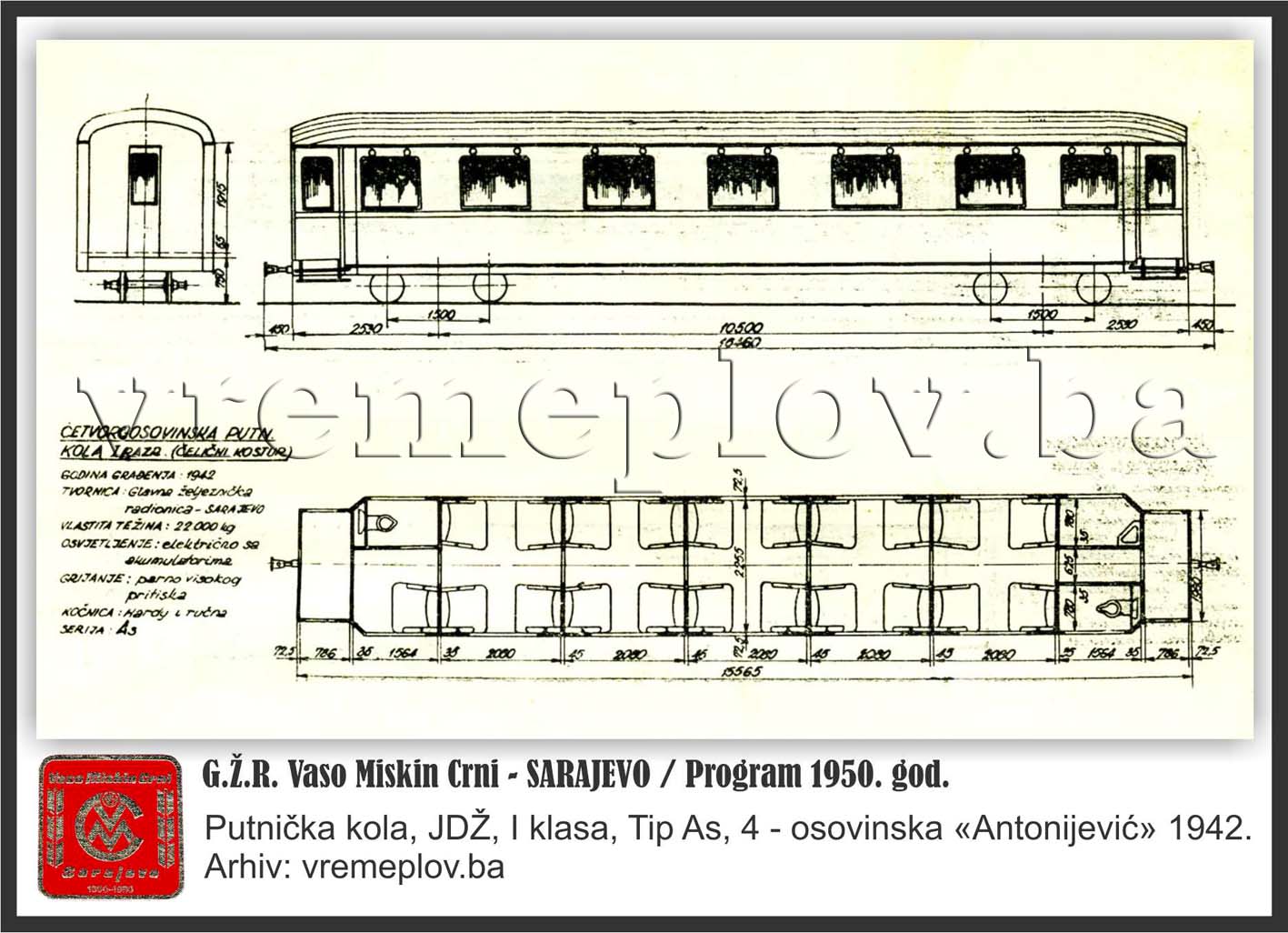

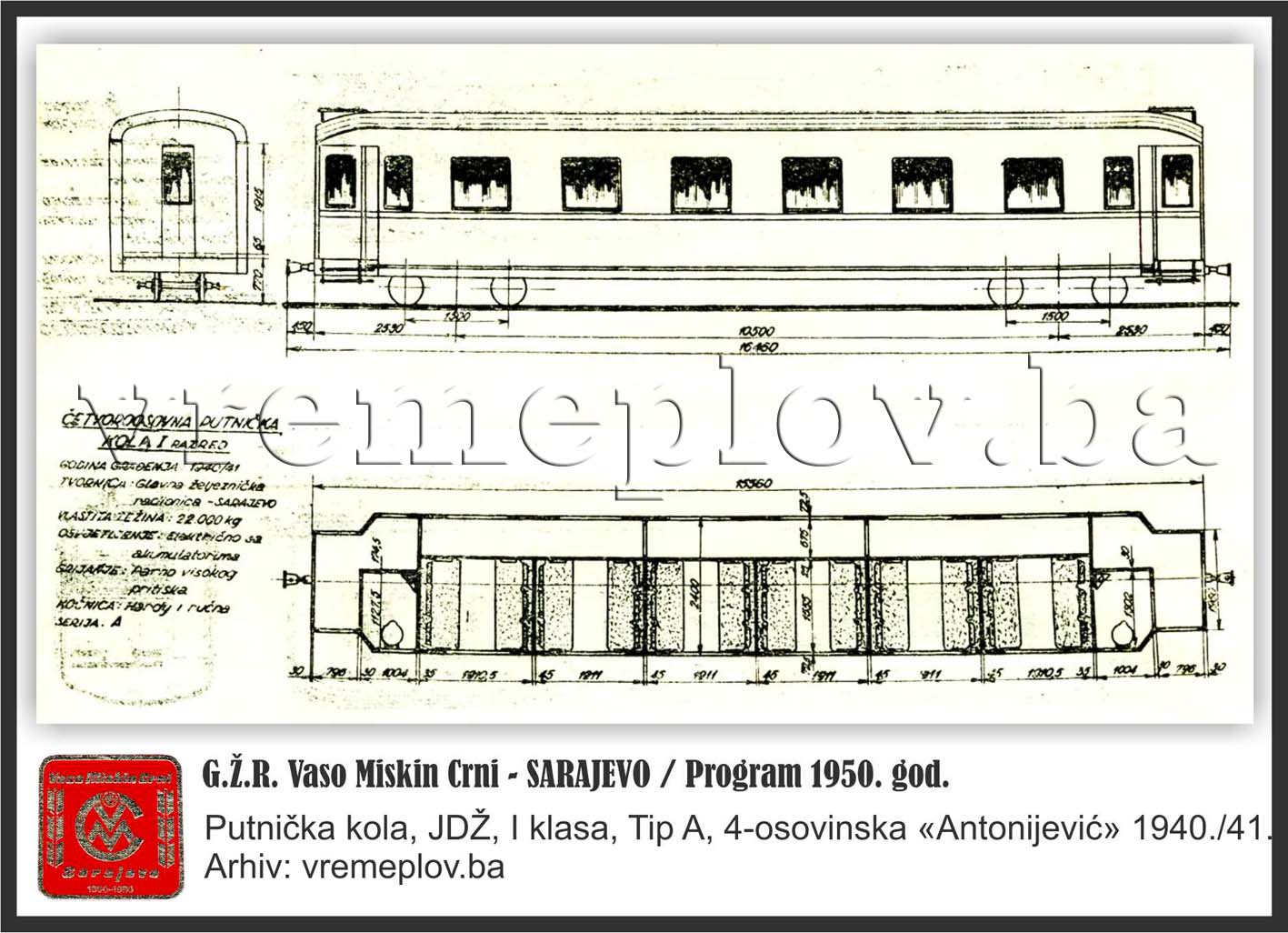

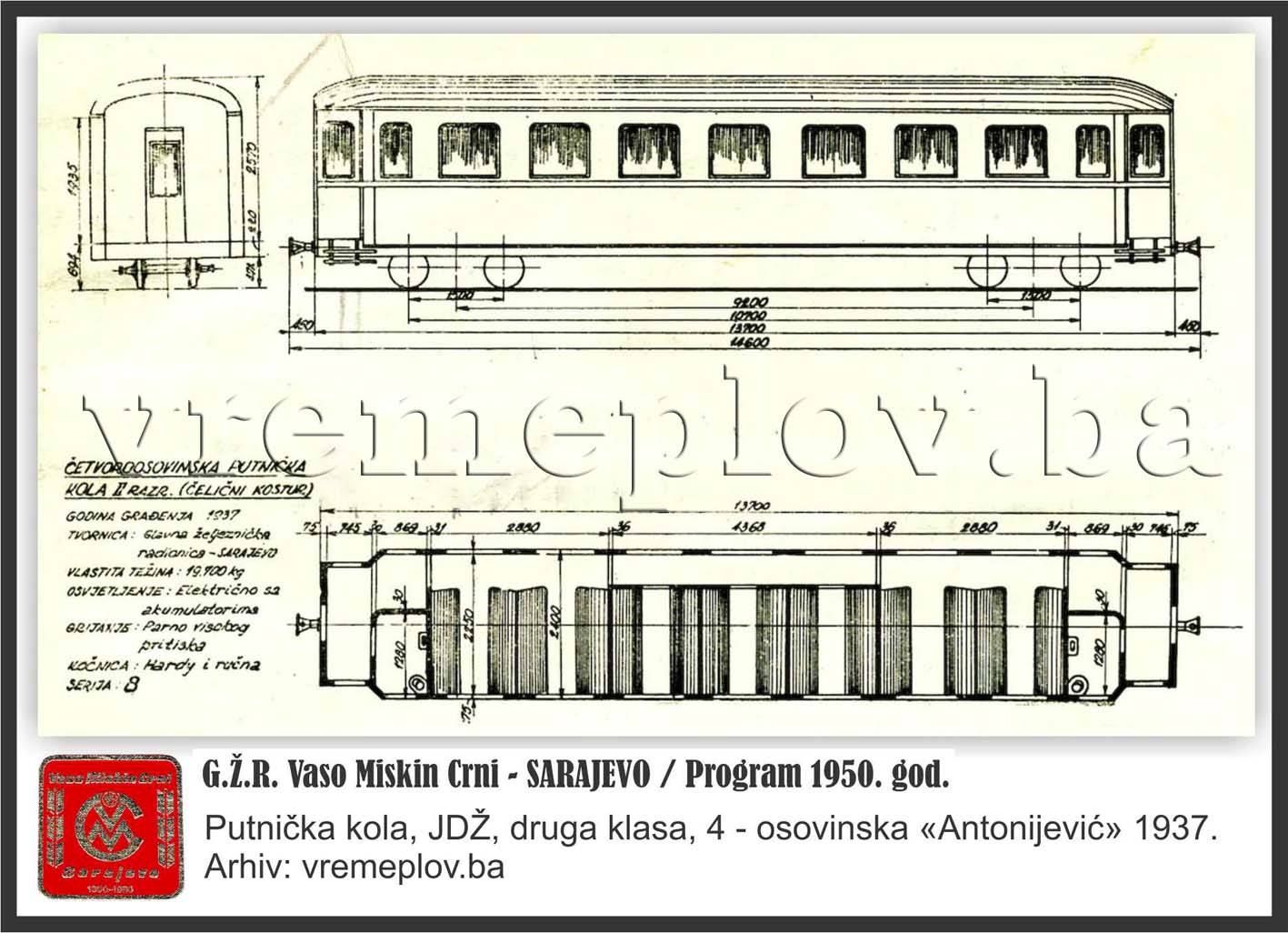

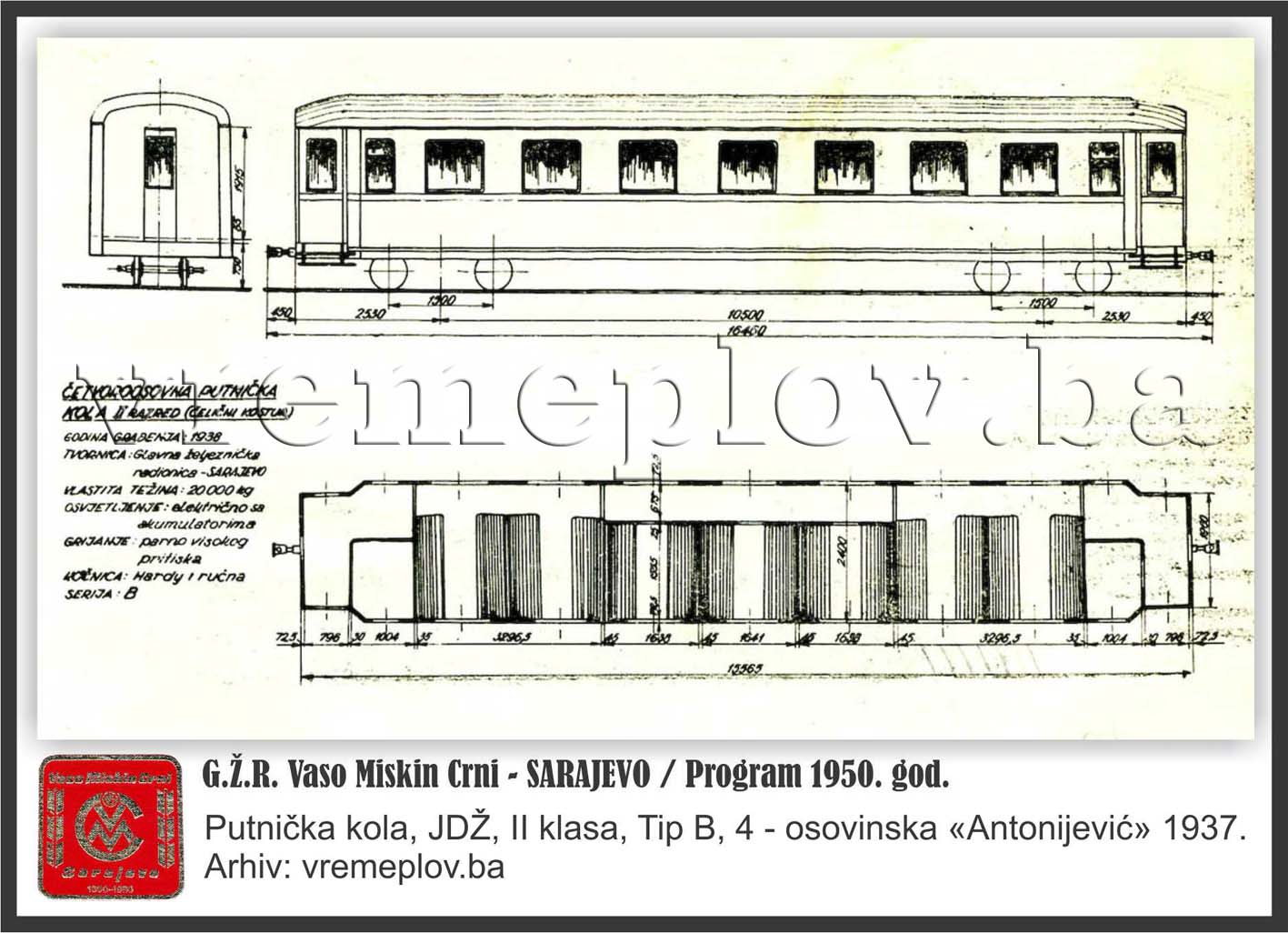

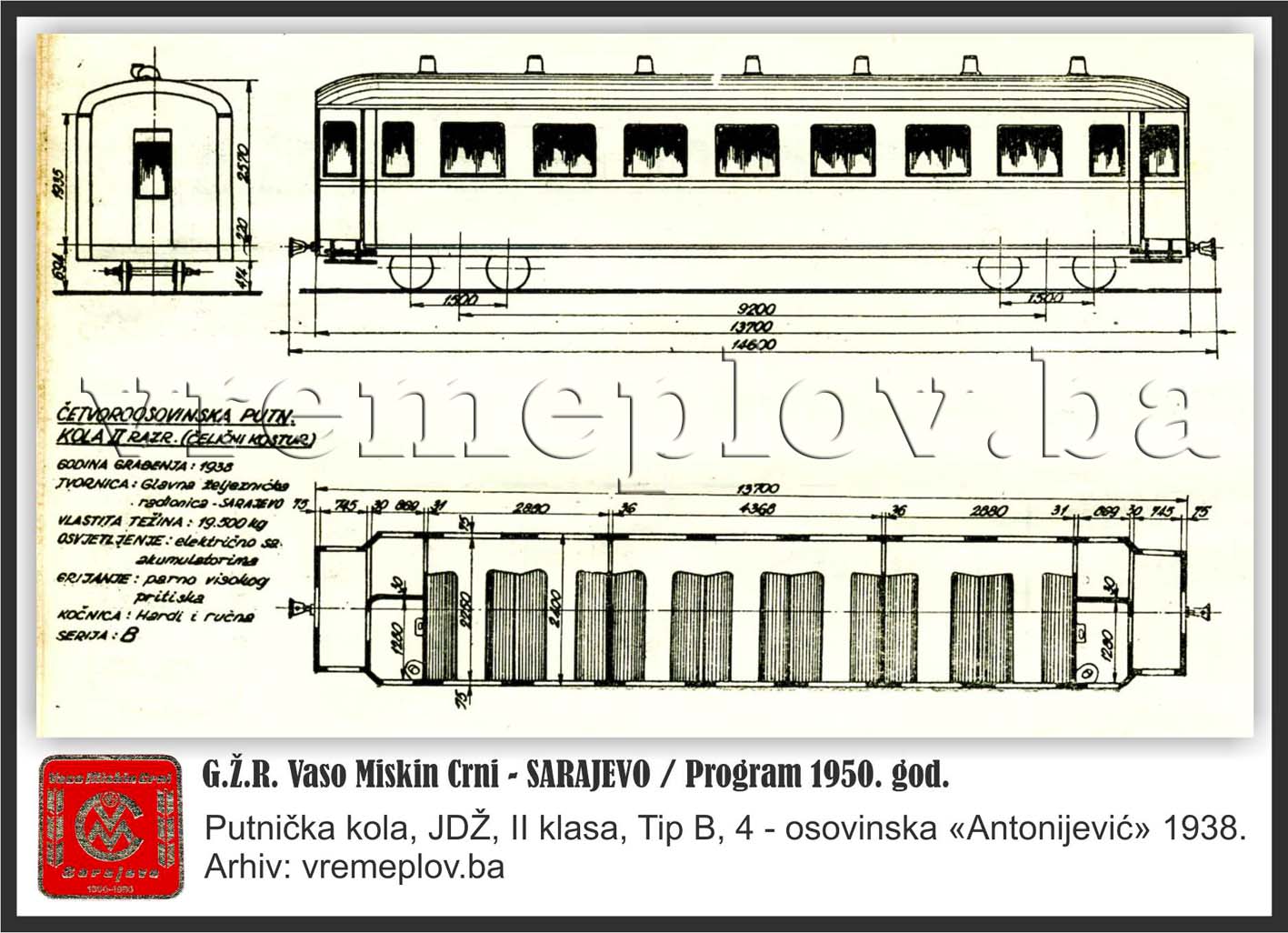

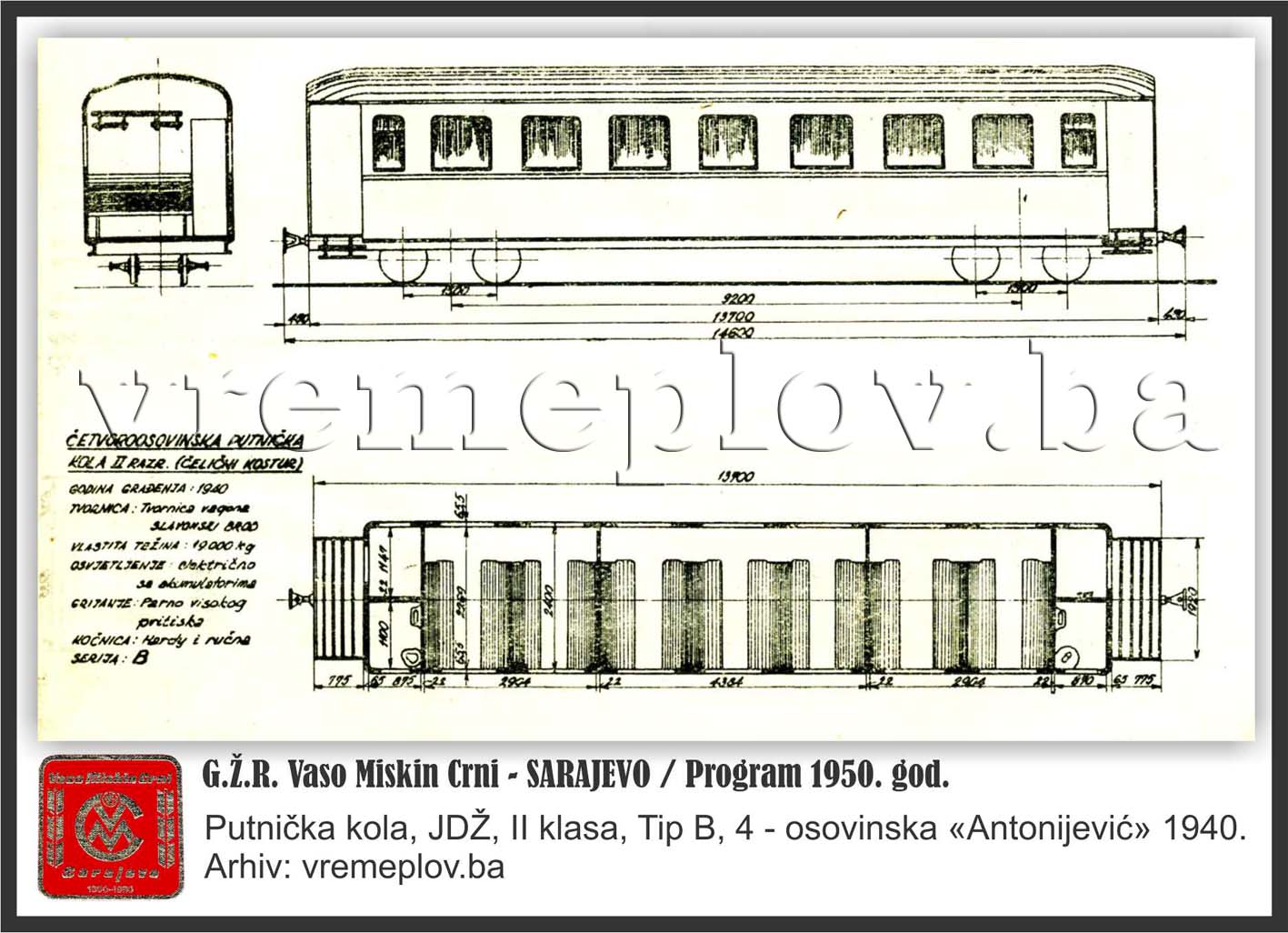

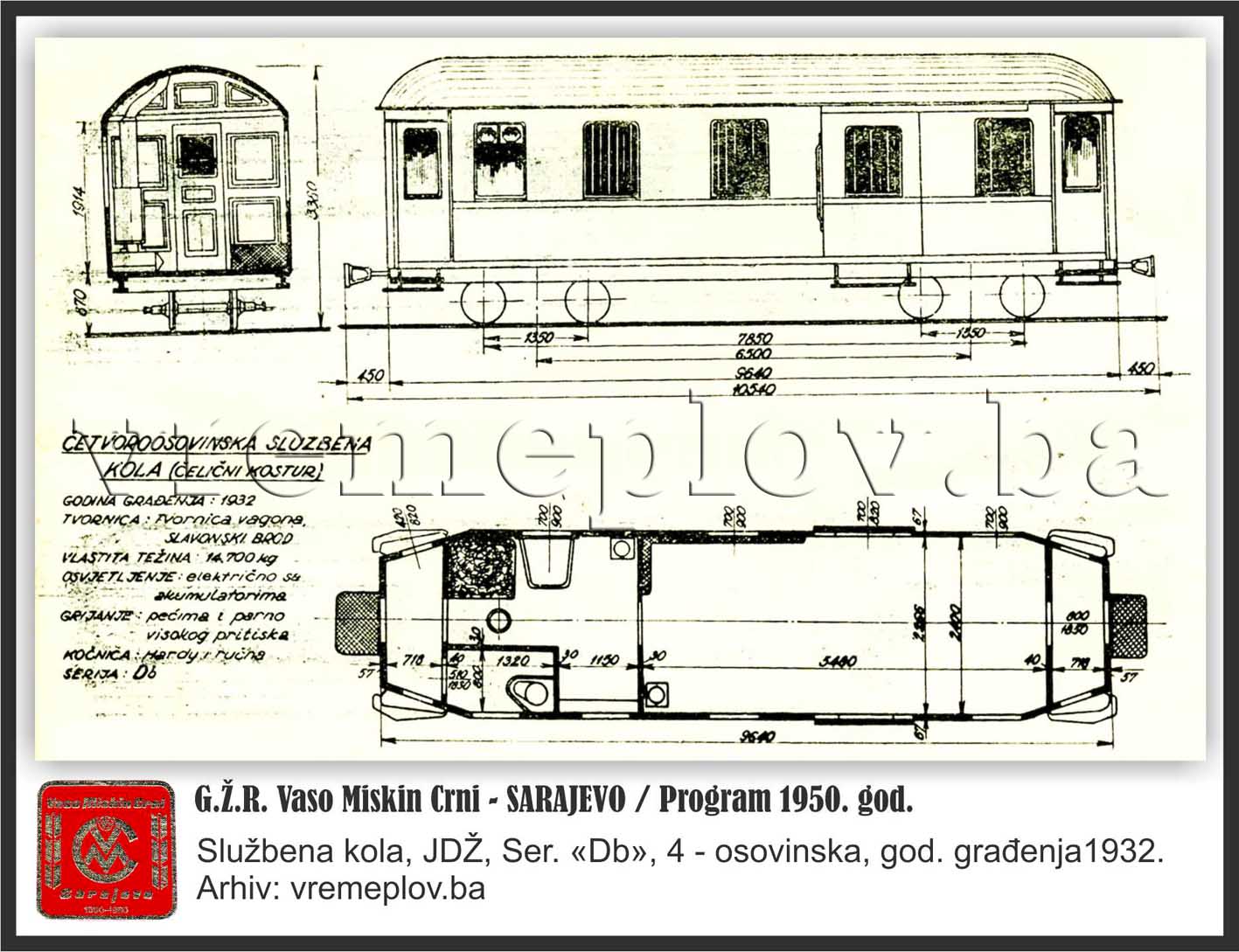

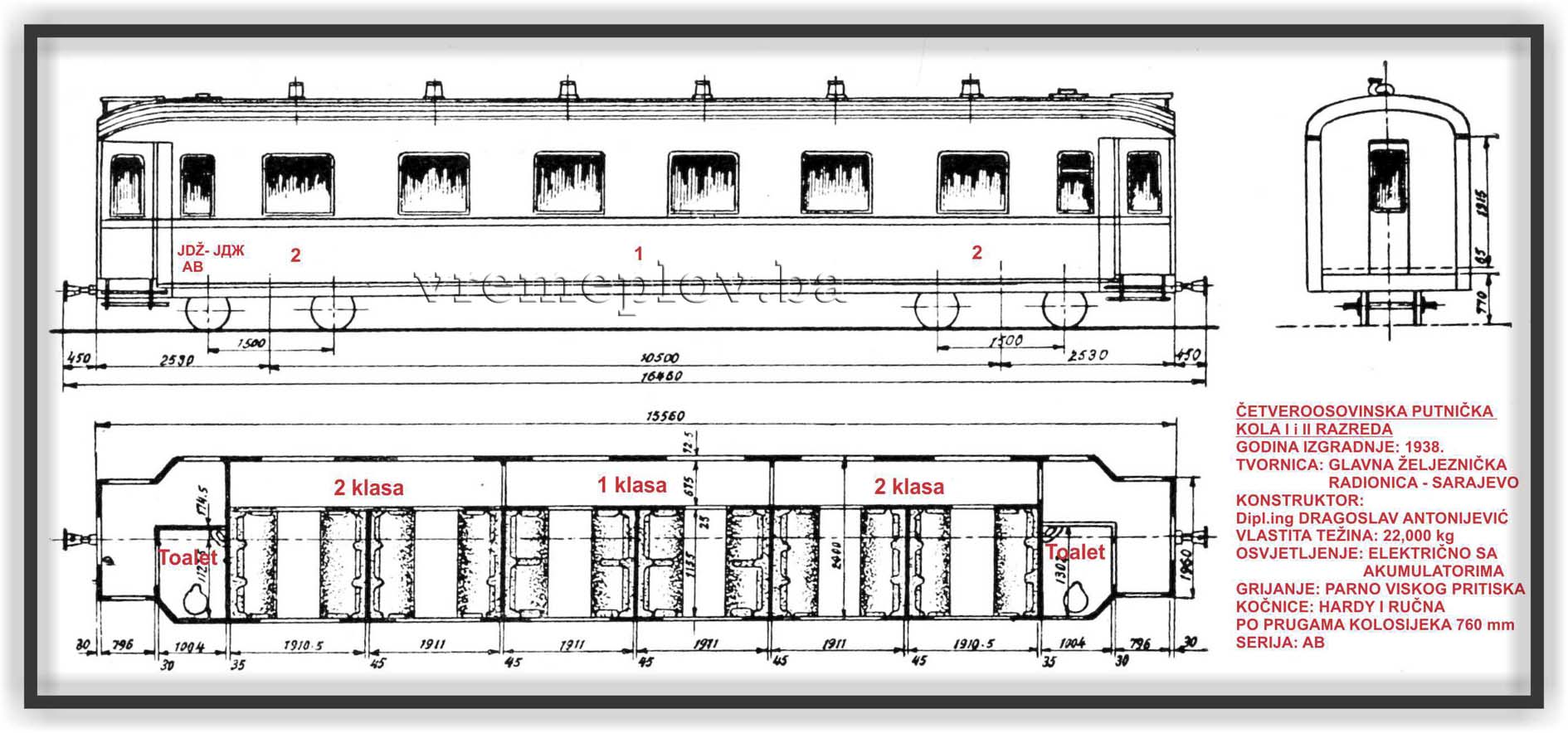

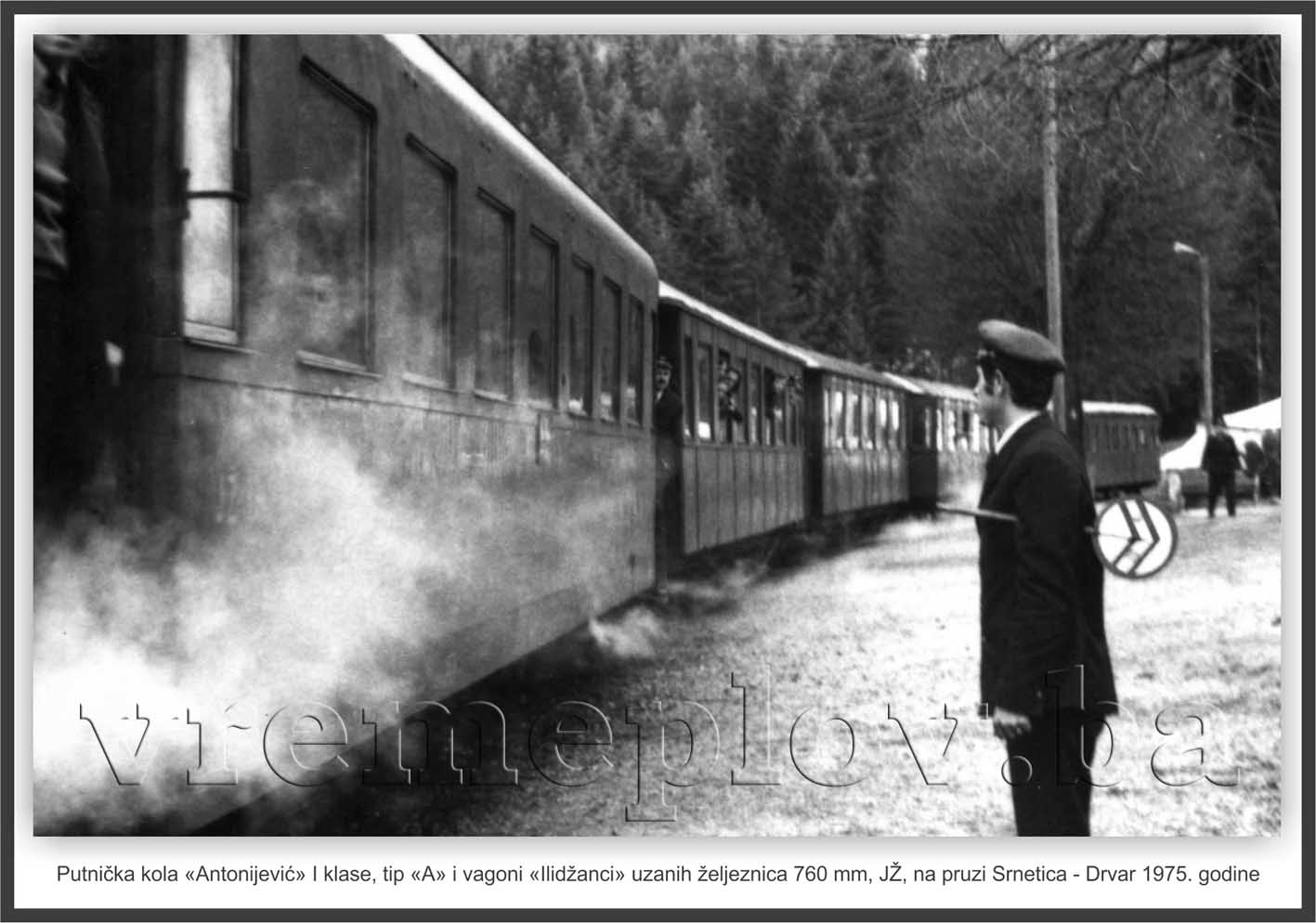

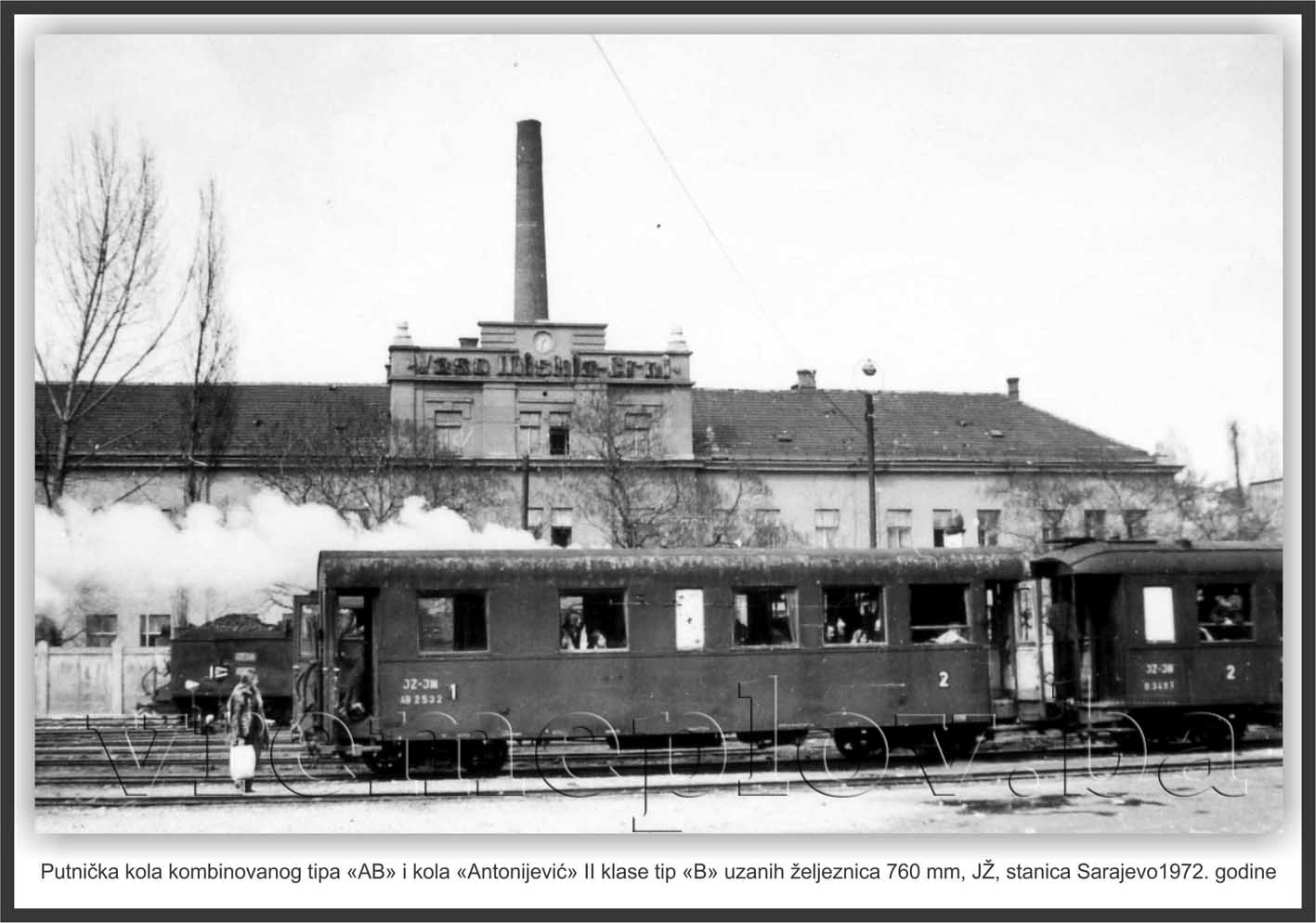

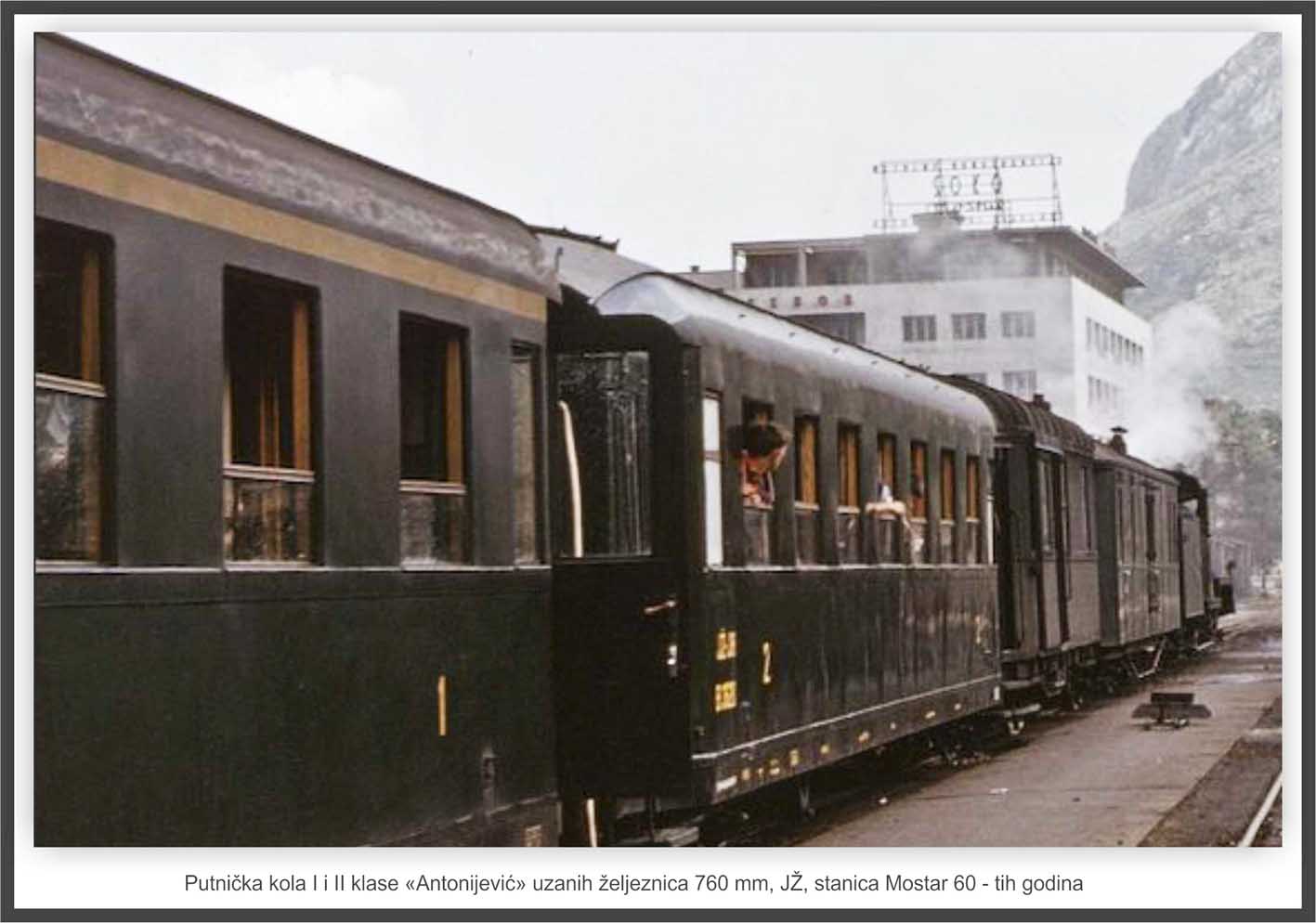

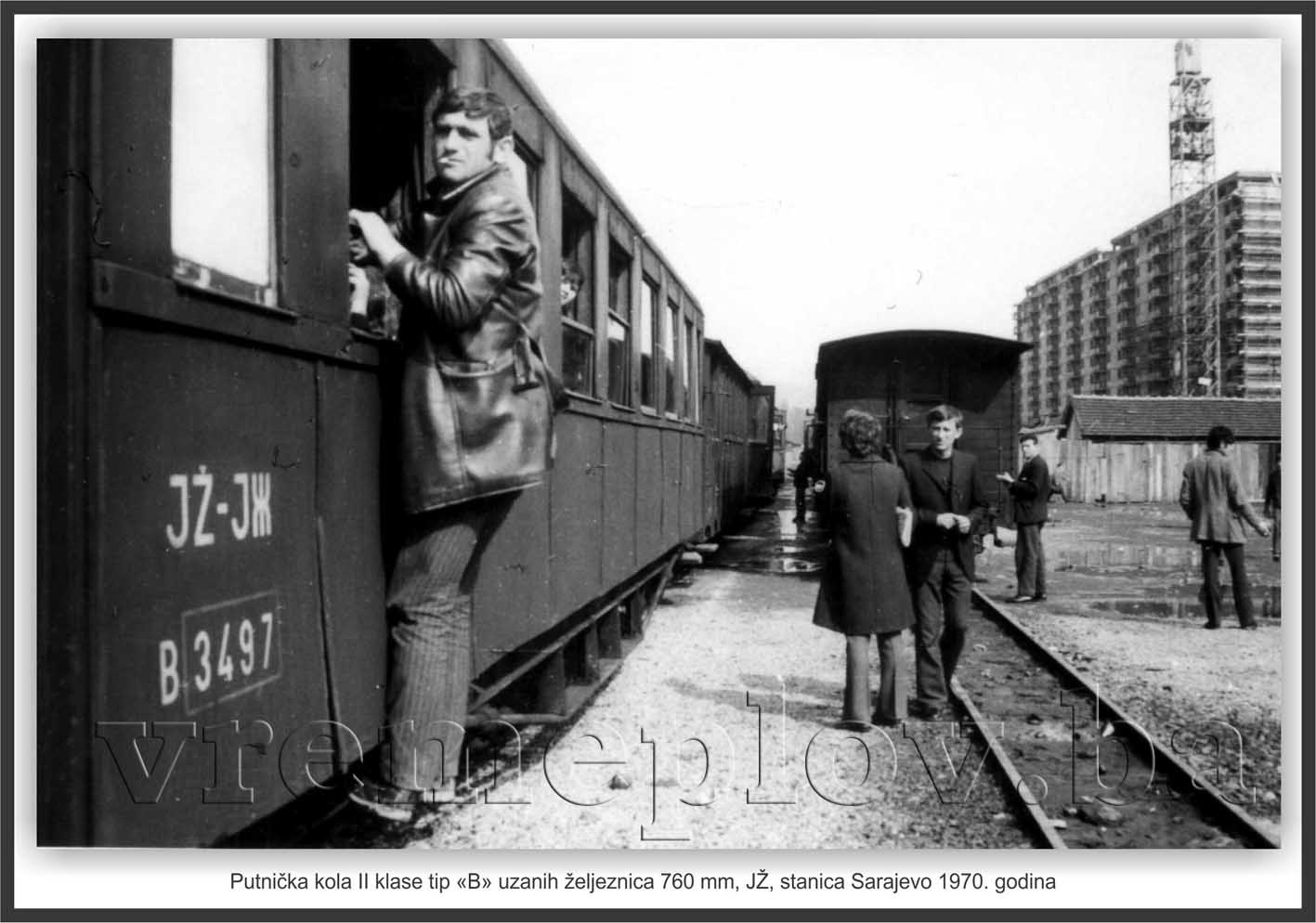

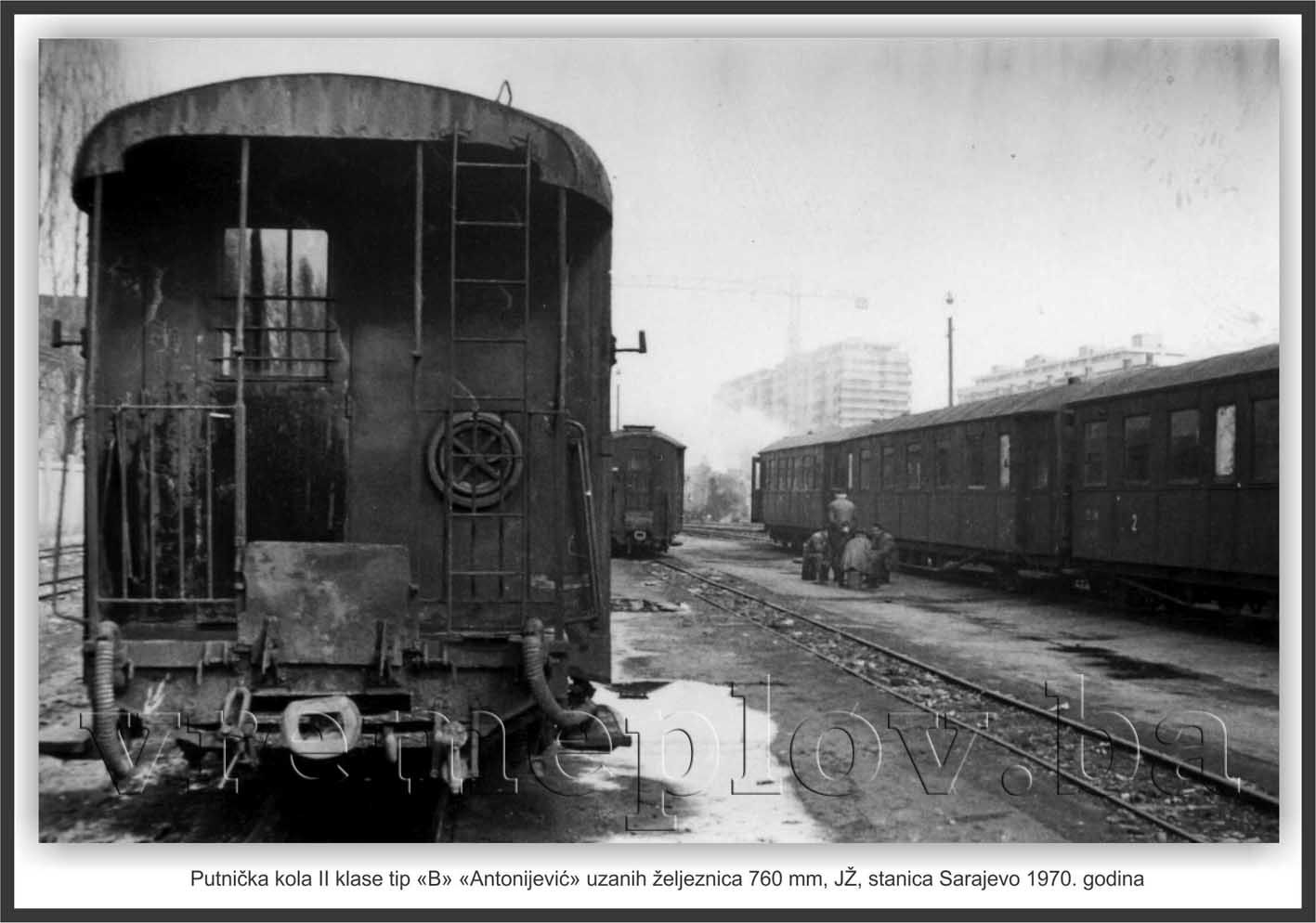

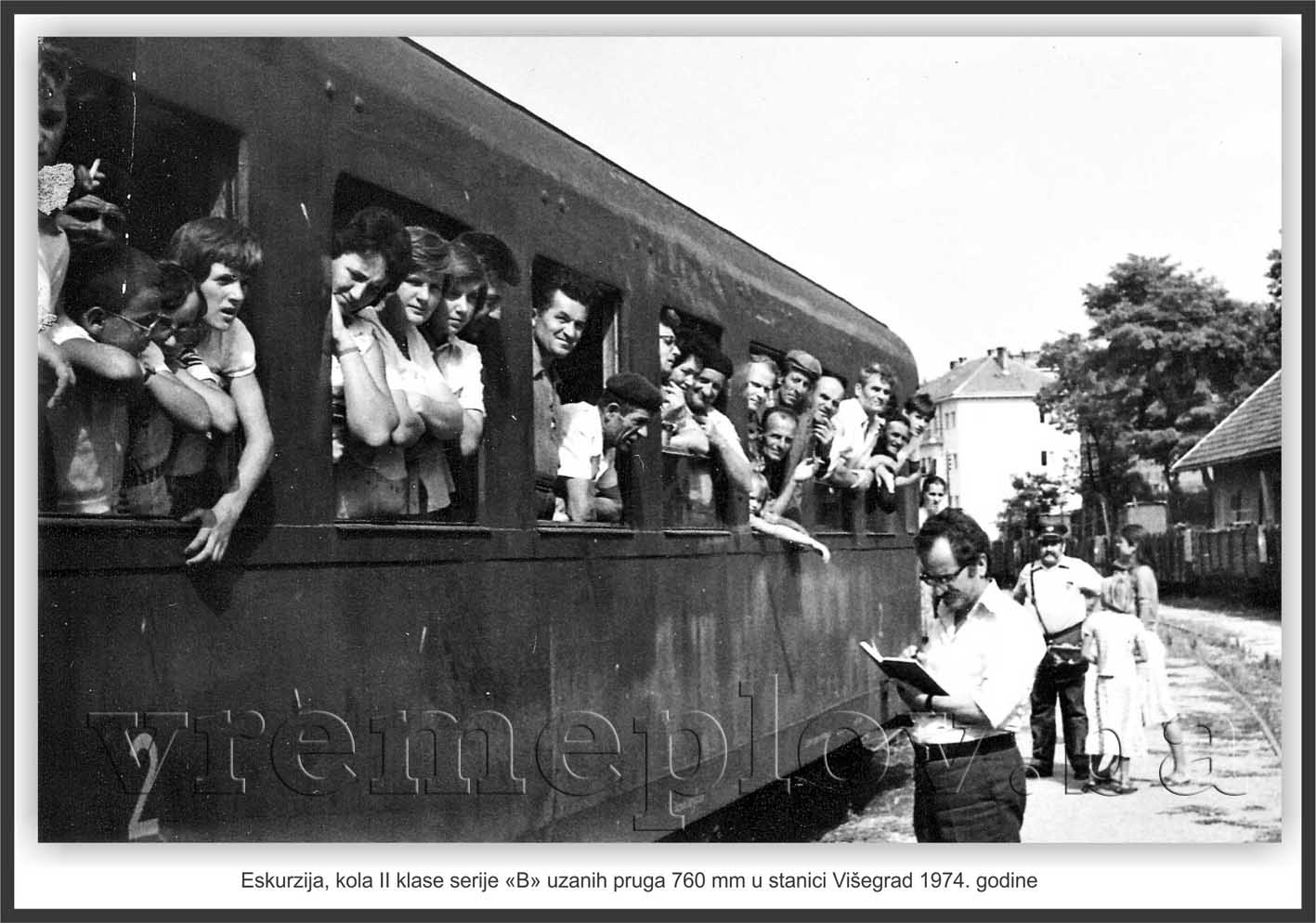

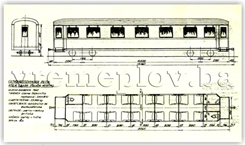

The primary construction material for the cars was obtained exclusively from abroad, making the finished cars quite expensive compared to those built in the state railway workshops. In an effort to eliminate the influence of such a “production” method of wagons, the State Railway Workshop in Sarajevo, led by engineer Dragoslav Antonijević, succeeded in developing an initial project and later produced several types of narrow-gauge passenger cars. One of the types that fully met all modern transportation requirements was made of lightweight steel construction, 14.46 meters long, with four-axle rotating bogies, connectors (for transitioning from one wagon to another), and other specialized devices (electric lighting, toilets, etc.), and served as a model and ultimately as a template for many foreign railway administrations. This wagon type (series “AB”) had six compartments: two first-class compartments with a total of 8 seats, and four second-class compartments with a total of 24 seats. Later, just before the outbreak of World War II, the Sarajevo railway workshop produced wagons of the same steel construction type in series “As” (with a central corridor) first class with a total of 20+1 seats, then series “A” (side corridor) first class with a total of 36 seats, and series “B” (second class, with seven compartments) with a total of 42 seats. In preparation for factory production of this narrow-gauge wagon type, they quickly began manufacturing in workshops in Zagreb and Ljubljana. The wagon type was named “Antonijević Wagons” in honor of the creator and designer, engineer Dragoslav Antonijević.

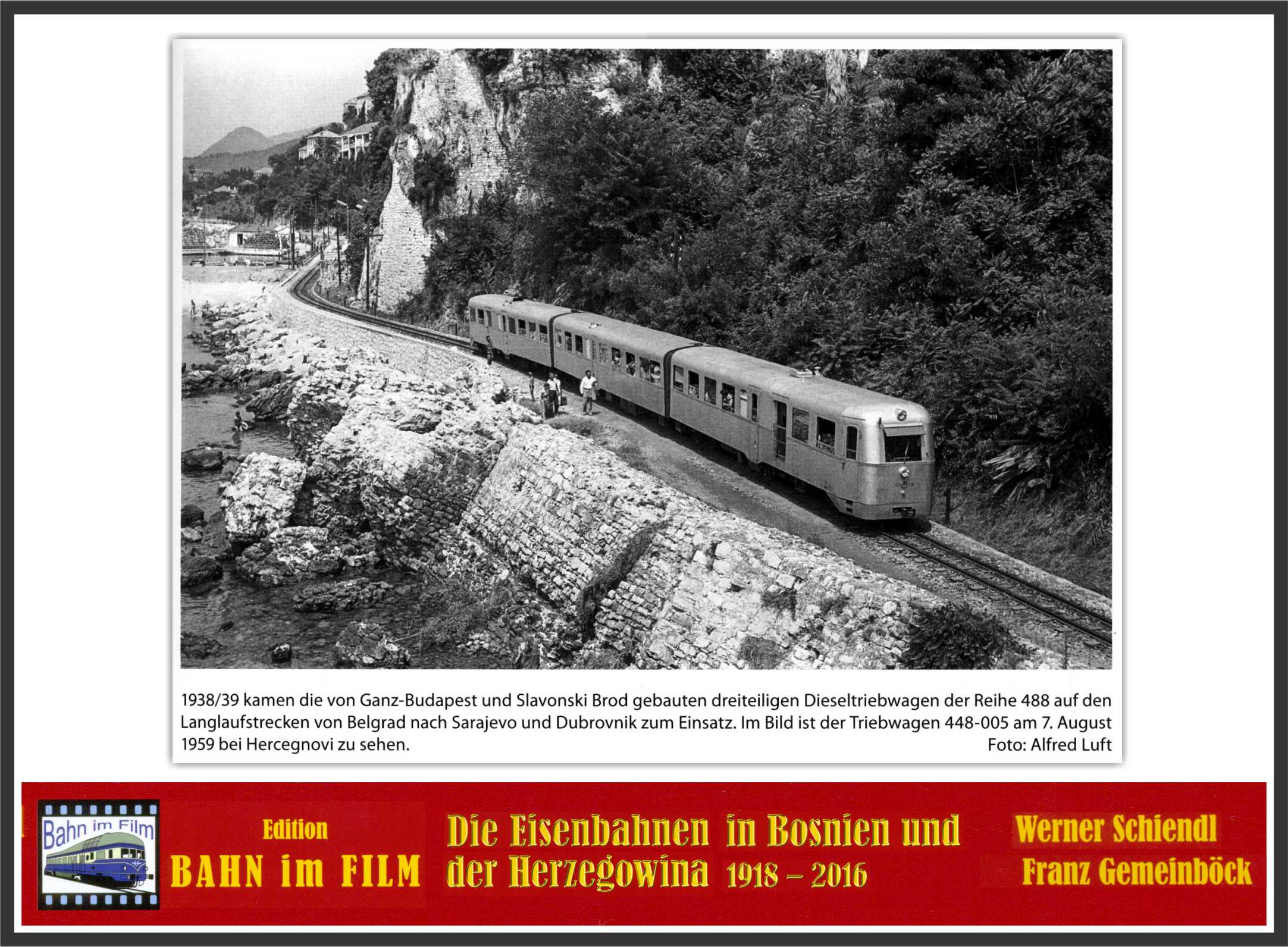

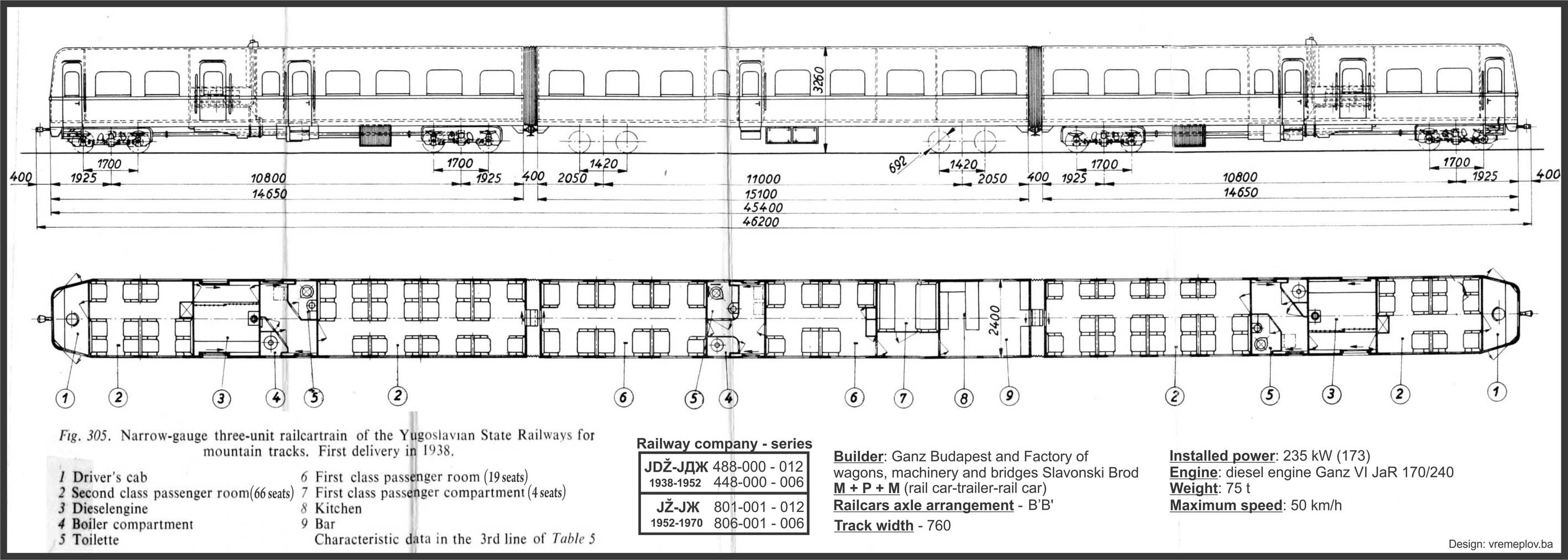

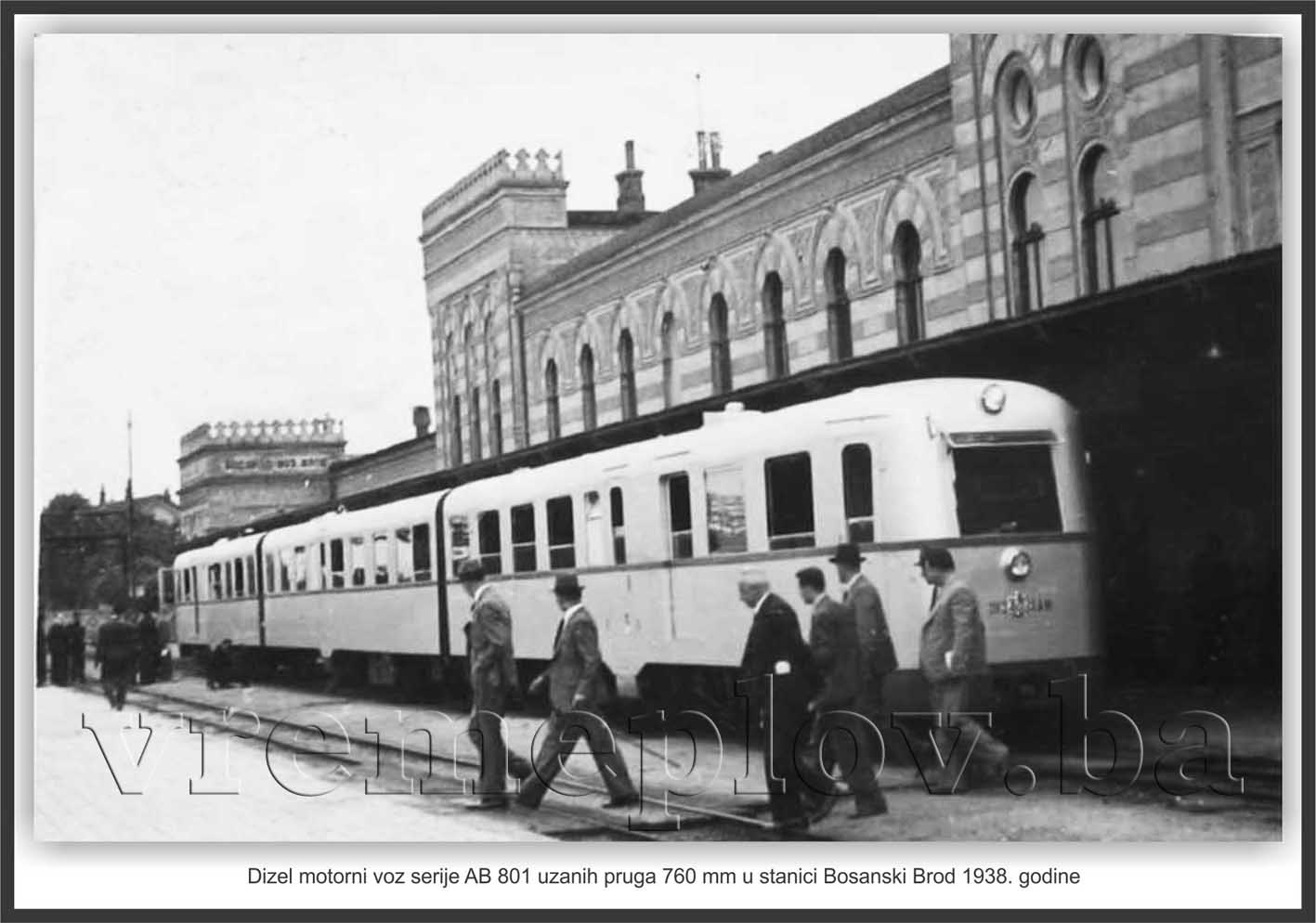

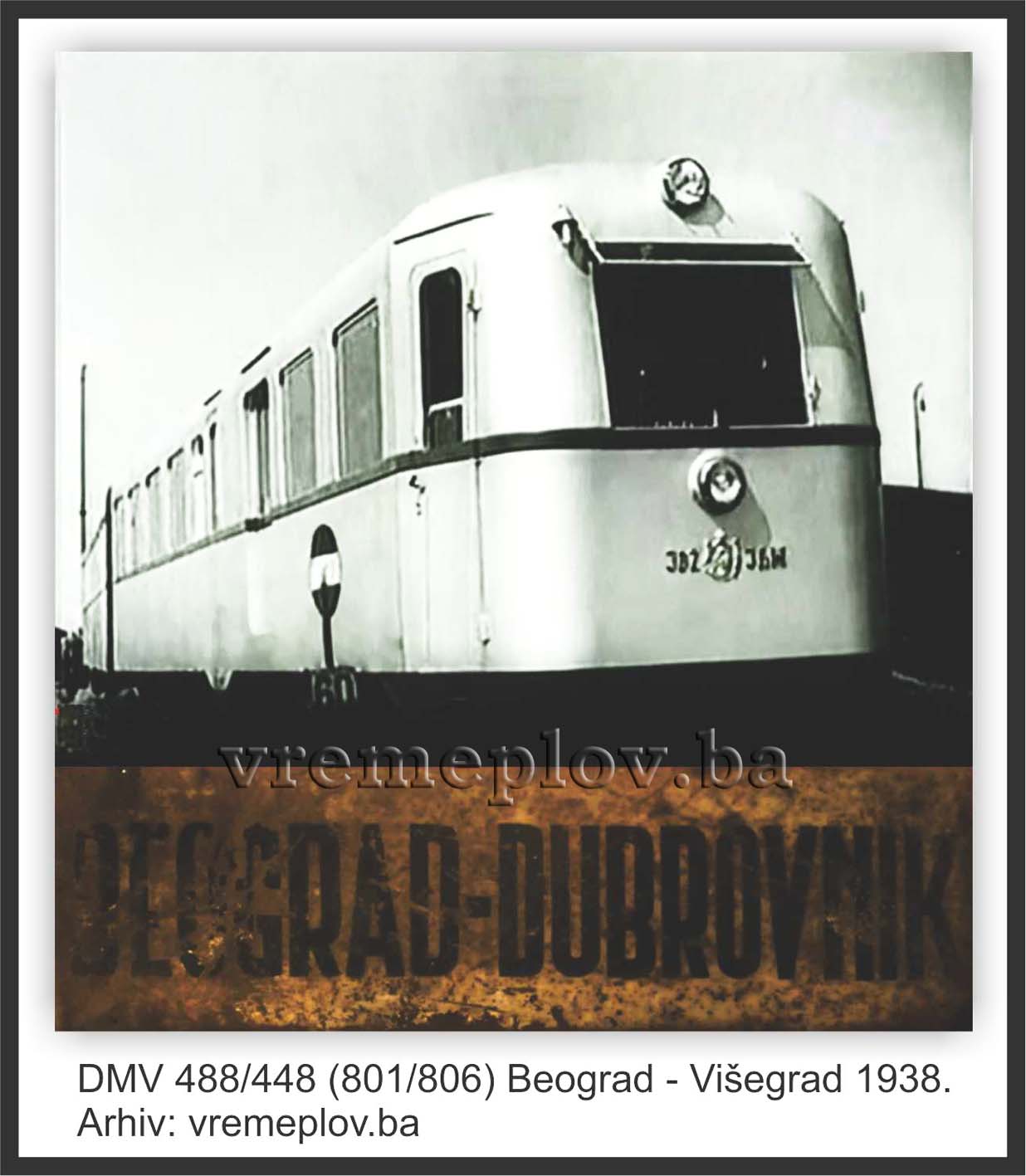

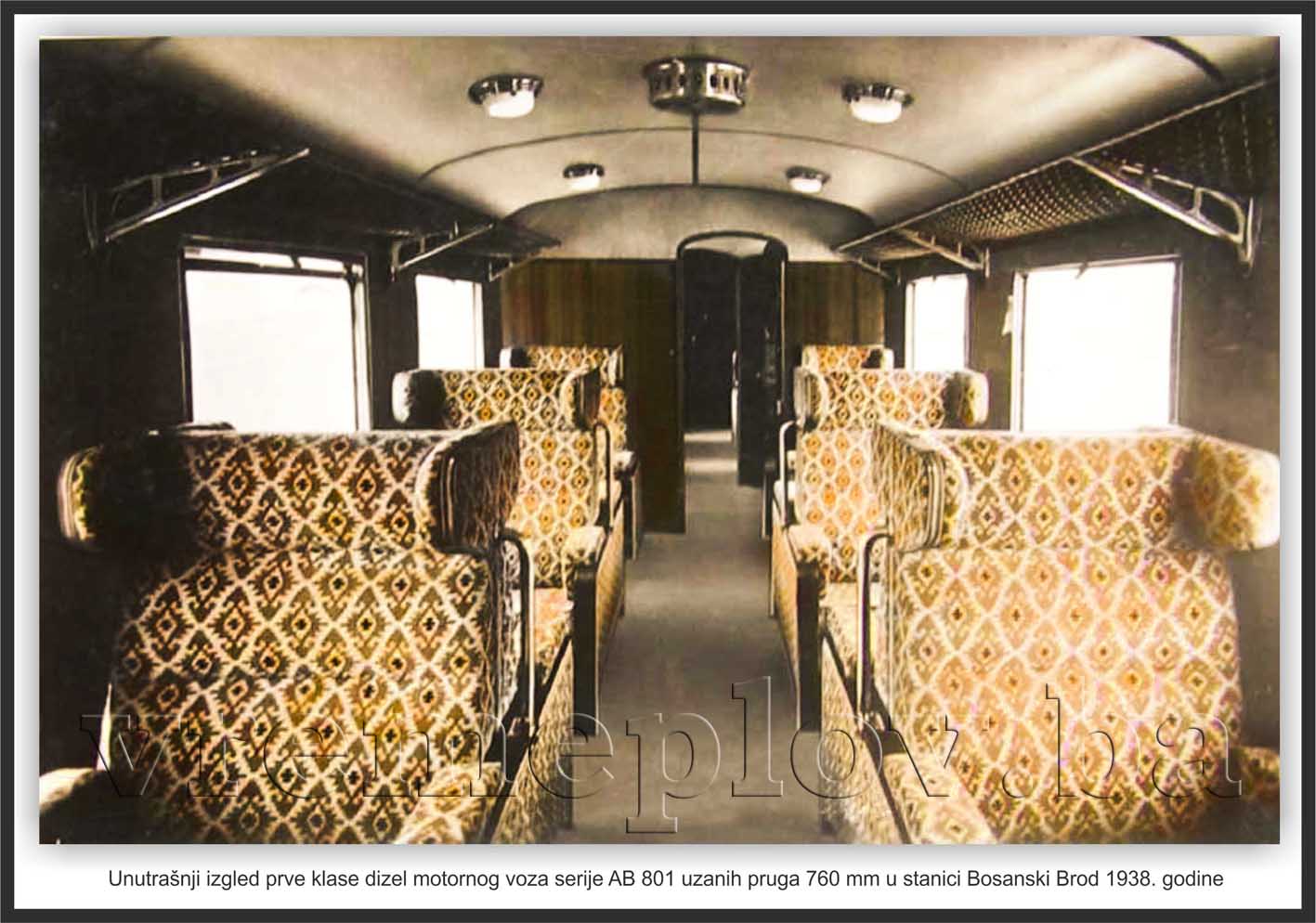

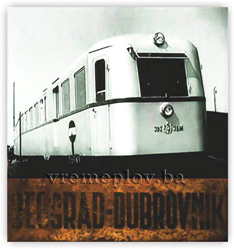

By the course of 1935, the JDŽ Railroad Administration began studying a rapid connection between Belgrade and Dubrovnik/Herceg Novi via Sarajevo. They were very popular among frequent travelers because they were more suitable for both rapid long-distance and local railway traffic. As early as 1938, seven such train sets (gauge 0.760 m) were ordered. The ordered motor trains consist of three cars: two end cars (power cars) powered by a diesel engine (Ganc Jendrasik with a power of 235/275 H.P.) and one trailer in the middle. They were equipped with the „Božić“ brake system, and in case of danger, also with an electromagnetic track brake system. All cars had four axles. The power cars had 66 seats of second class, and the trailer had 23 seats of first class and one section for a café.

The first of the seven sets ordered was delivered from the Ganz factory in Budapest. Specifically, the type of this locomotive was produced in cooperation between Ganz (diesel-mechanical drive and interior) and the machinery and wagon factory in Slavonski Brod (bodywork). Later on, the assembly of the remaining ordered motor trains was carried out at the Slavonski Brod factory.

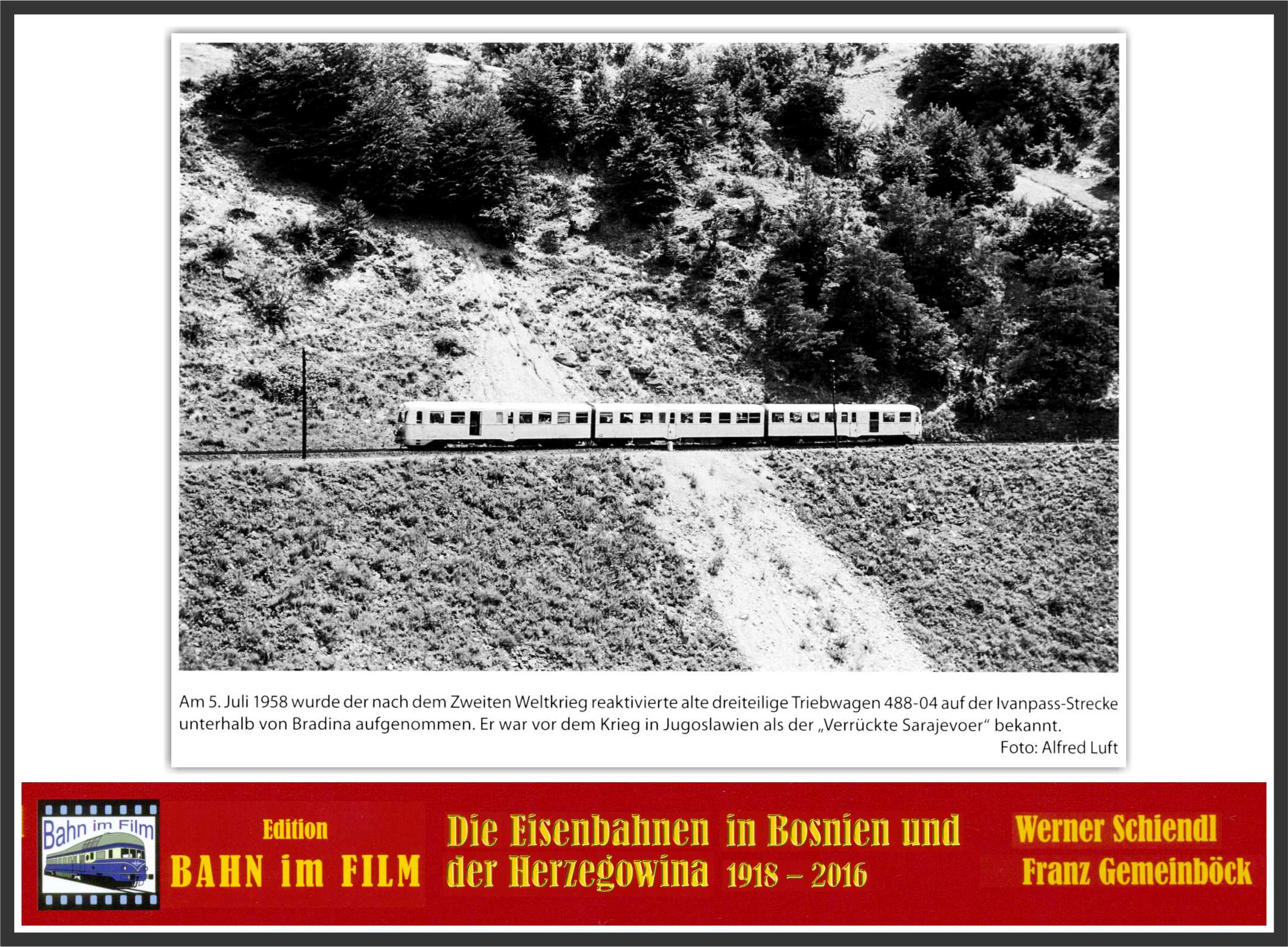

They officially carried the designation of the series MV (DMV) 488/448 (488 – power units, 448 – trail cars). Under full load (74 tons), on a level track, it could reach speeds of up to 60 km/h (never achieved on Bosnian narrow-gauge lines), on inclines of up to 20 ‰ up to 48 km/h, and up to 60 ‰ on cogwheel tracks up to 20 km/h. For example, a steam train on the route Belgrade – Sarajevo – Dubrovnik traveled in 24 hours, while these motor trains covered the same distance in 16 hours and 30 minutes. At that time, these motor trains gained a charming nickname, “Crazy Sarajevan.” With their introduction into service from 1945, they were marked by a new series 801/806.

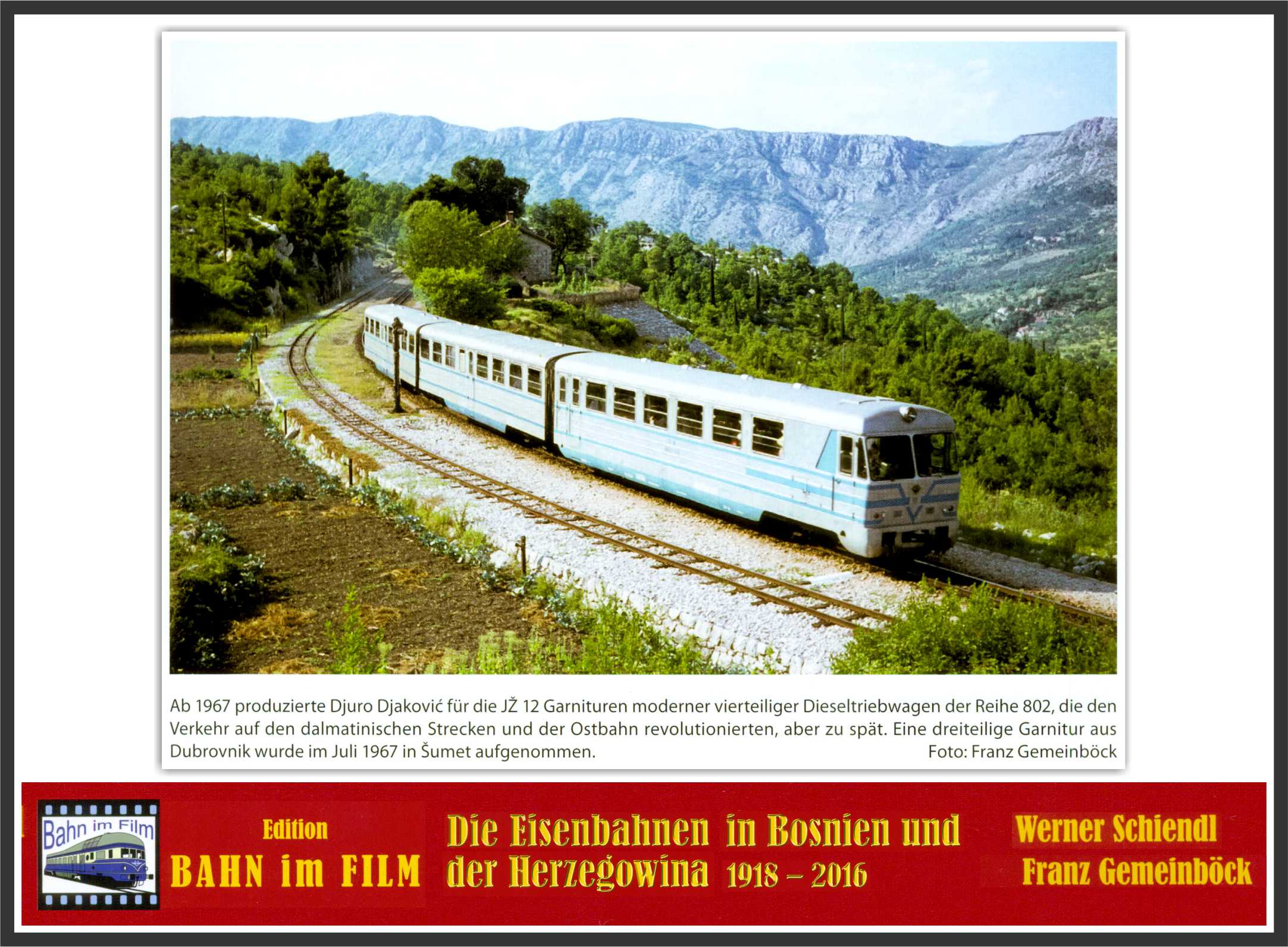

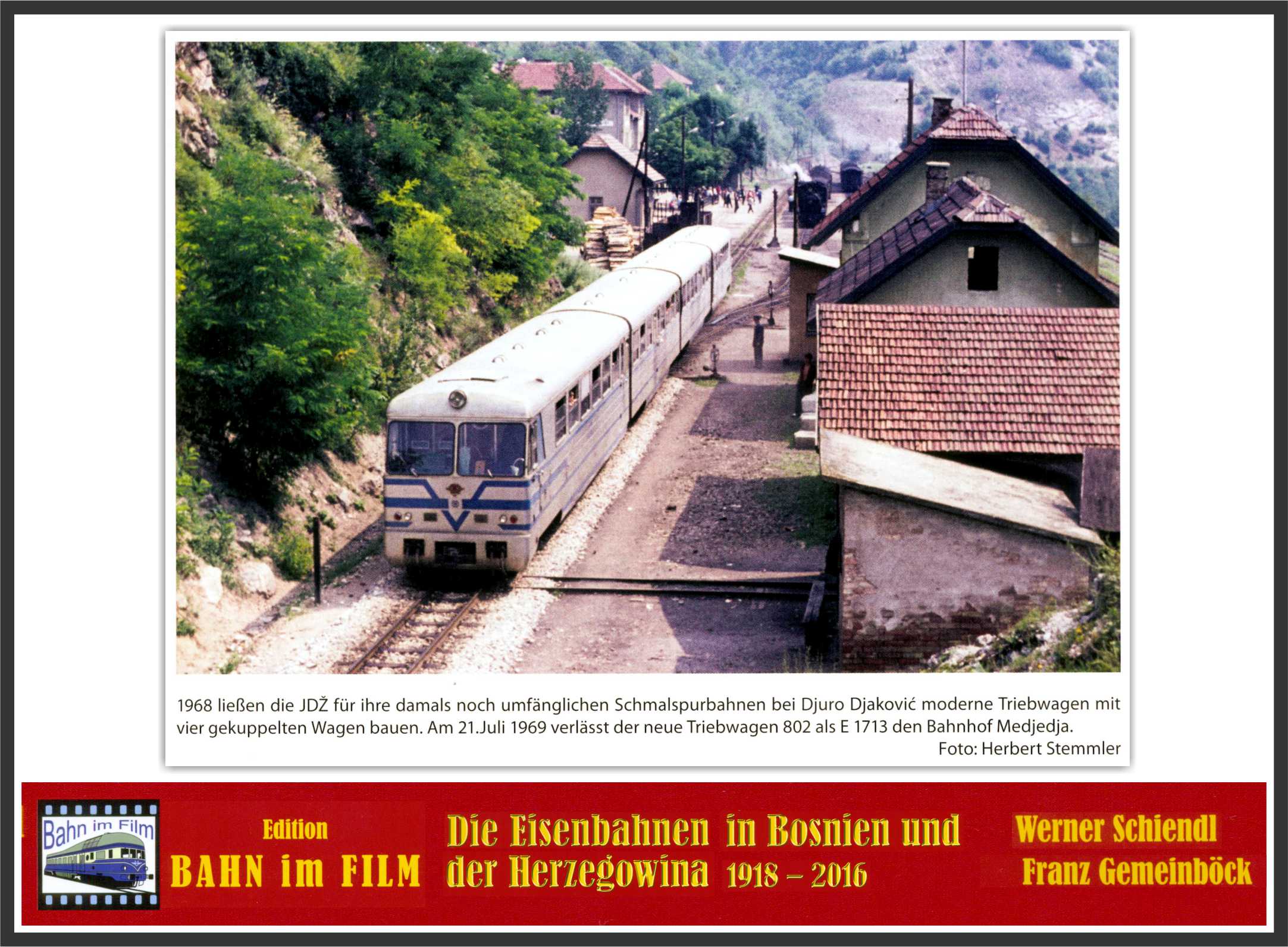

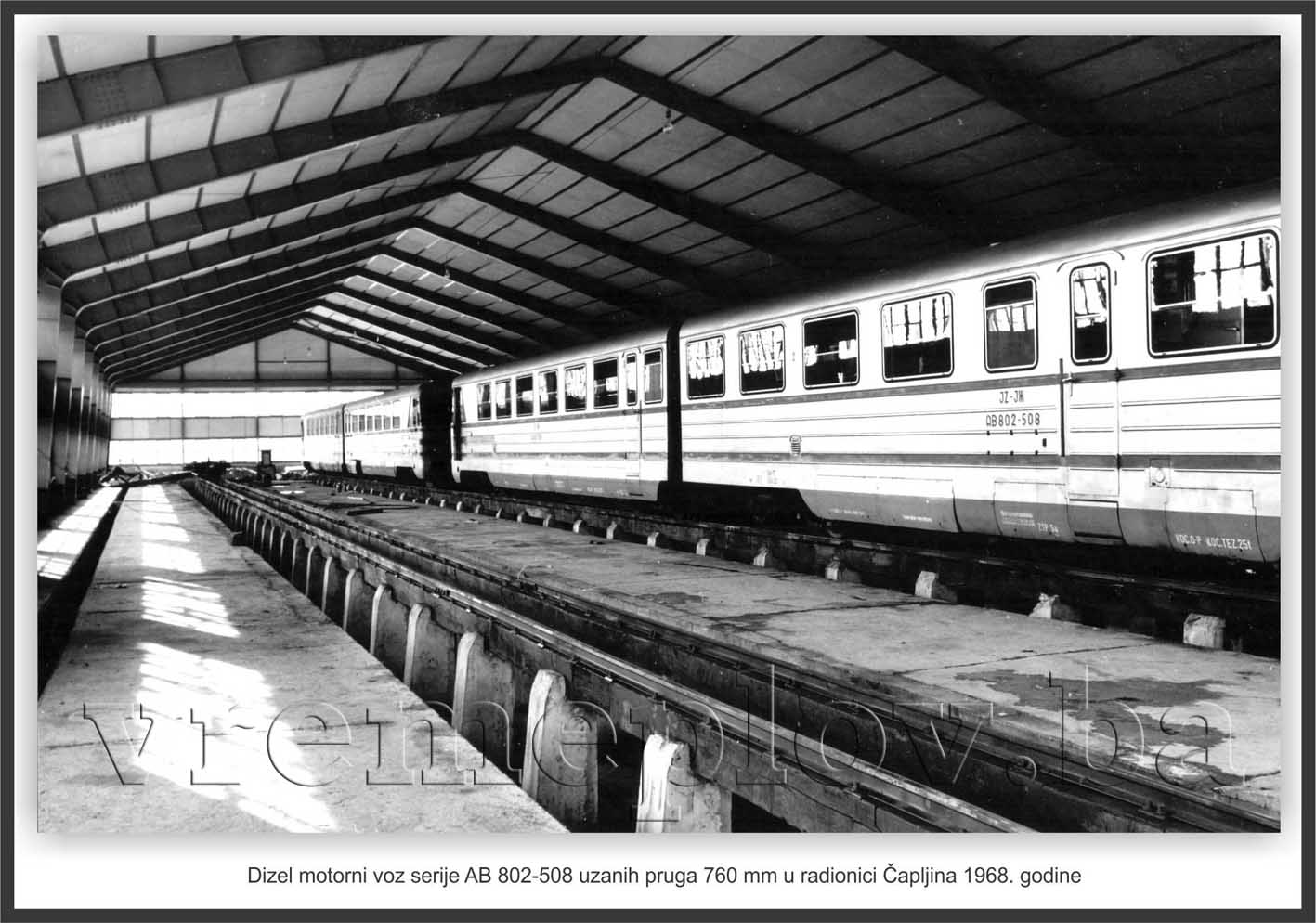

After the end of the war, this series of motor cars operated for a long time along the narrow gauges of Bosnia and Herzegovina until the late 1960s, when they were replaced by new and more modern four-part motor cars produced at the “Đuro Đaković” factory in Slavonski Brod, equipped with “Fiat” engines (designation “FIAT type 221 H. O710 with a nominal engine power of 185 horsepower). The train was 60 meters long, and the total number of seats in the train was 152+8+2. It bore the official series designation MV (DMV) 802. The train’s braking was regulated by the “Božić” braking system, and in case of danger, a magnetic track brake was used. Heating in the train was technically provided directly by the engine, and at lower temperatures, a “Webasto” device (Webasto heating) was also activated. These motor cars remained in service until the very last days before the abandonment of the narrow gauge lines in BiH.

If we were to make an assessment of the development of passenger traffic and narrow-gauge wagon industry in Bosnia and Herzegovina by 1945, we can state that it was quite poor. Aside from foreign two-axle and three-axle wooden boxcars, repair-related cars, a few designs of four-axle cars that came out of state workshops, and a very small number of cars produced in domestic private factories, none of these remotely met the needs of railway traffic.

Rolling stock and passenger traffic on narrow gauge railway during socialism

After the end of World War II, the railway infrastructure (track facilities, bridges, workshops, locomotives, and rolling stock) in Bosnia and Herzegovina was found to be in a catastrophic state. Namely, starting from the fall of 1944, the Allied aviation began bombing military and industrial facilities as well as railway and road networks in the BiH area (Bosanski Brod, Doboju, Zenica, Podlugovi, Alipašin Most, etc.) under the control of Hitler’s ally, NDH. During the German army’s retreat from these territories, a significant devastation of the entire railway infrastructure was carried out (buildings, bridges, tunnels, etc.).

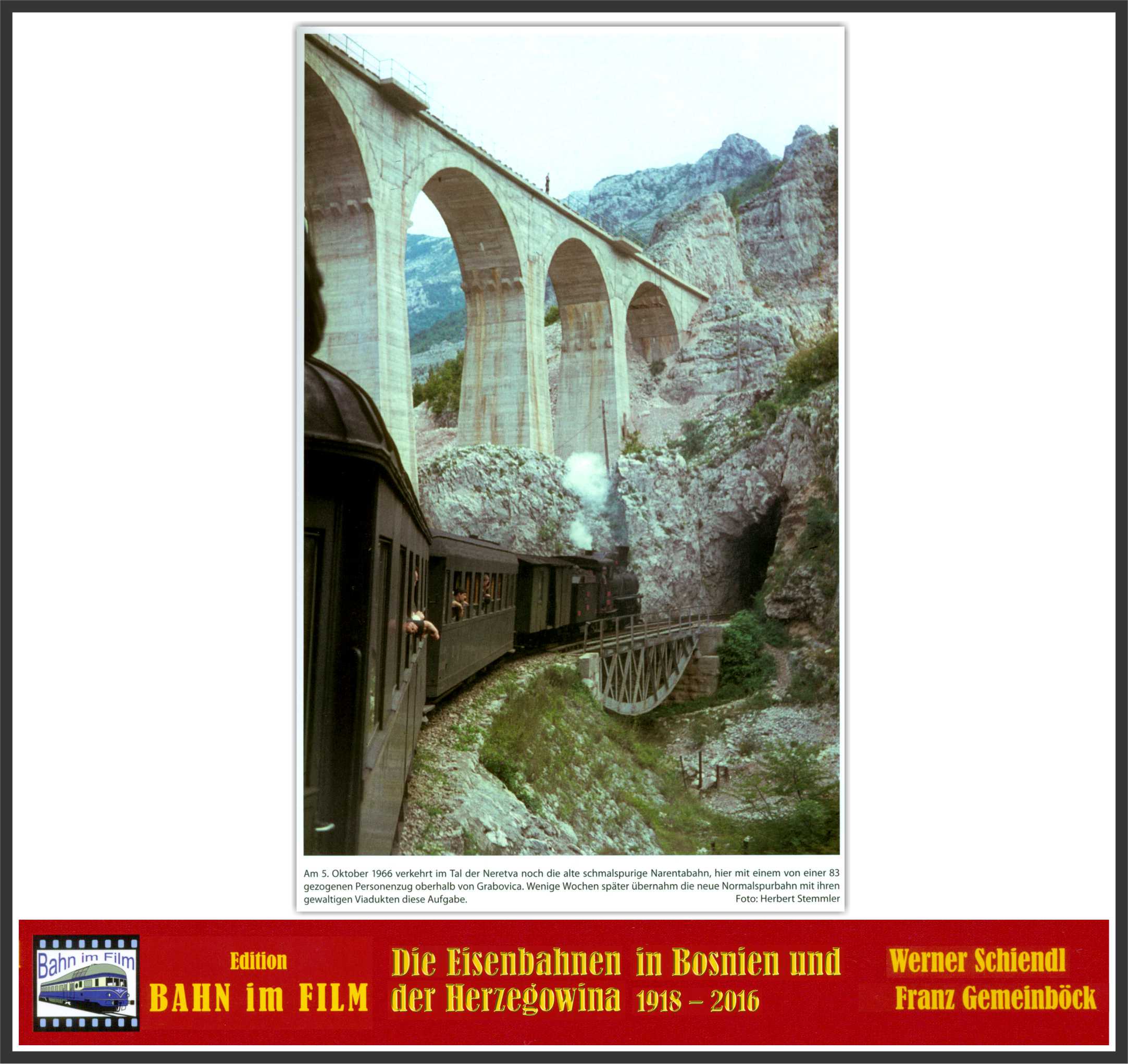

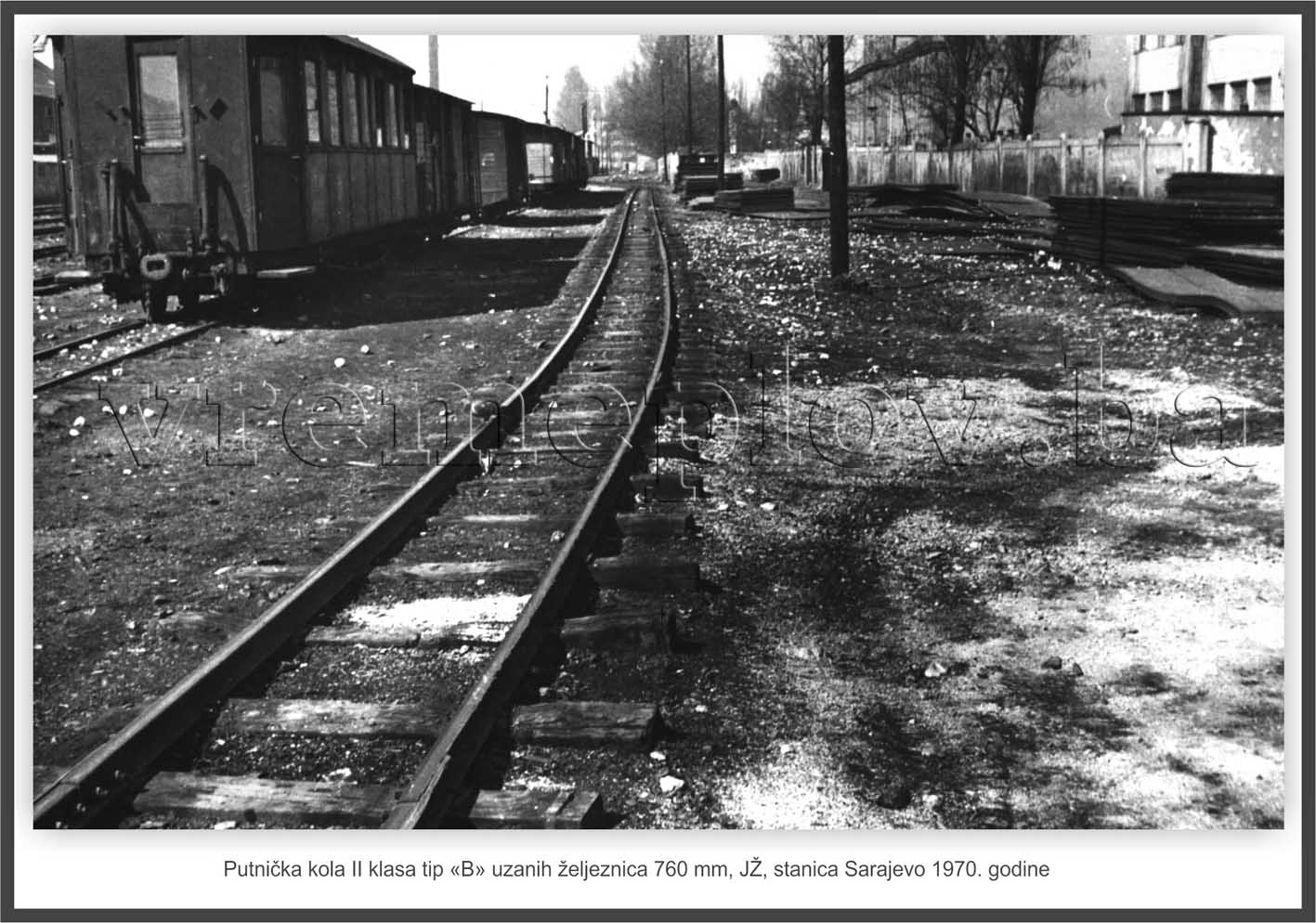

In addition to locomotive servicing, work on the rolling stock began immediately. Passenger coaches of narrow gauge, of various series and types, were severely damaged. The railway workshop in Sarajevo, along with many smaller workshops and boiler houses, immediately focused on repairs and refurbishing. Despite the shortage of skilled personnel, materials, and spare parts, remarkable results were achieved in a short period of time. The primary tasks of post-war reconstruction—restoring destroyed bridges, railway tracks, and roads—were mostly fulfilled. During the country’s reconstruction, the standard gauge track from Brčko to Banovići was built through Youth Work Actions. To accomplish the tasks outlined in the Five-Year Plan (the First Five-Year Plan for Industrialization and Electrification of Yugoslavia, 1947–1951), large factories and hydroelectric power plants, such as the Zenica steelworks and Jablanica hydropower plant, began construction. The future wagon industry depended on metallurgy. Bosnia and Herzegovina, as a resource-rich hub, could not fully satisfy industrial transportation needs with its narrow gauge capacity. In 1947, through a voluntary work action, the standard gauge railway from Šamac to Sarajevo was built. In the first half of the 1950s, the Doboj–Tuzla, Podlugovi–Vareš, and Doboj–Banja Luka lines were “normalized.” In the 1960s, specifically in 1966, the Sarajevo–Ploče line was “standardized,” which quadrupled freight and passenger transport in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

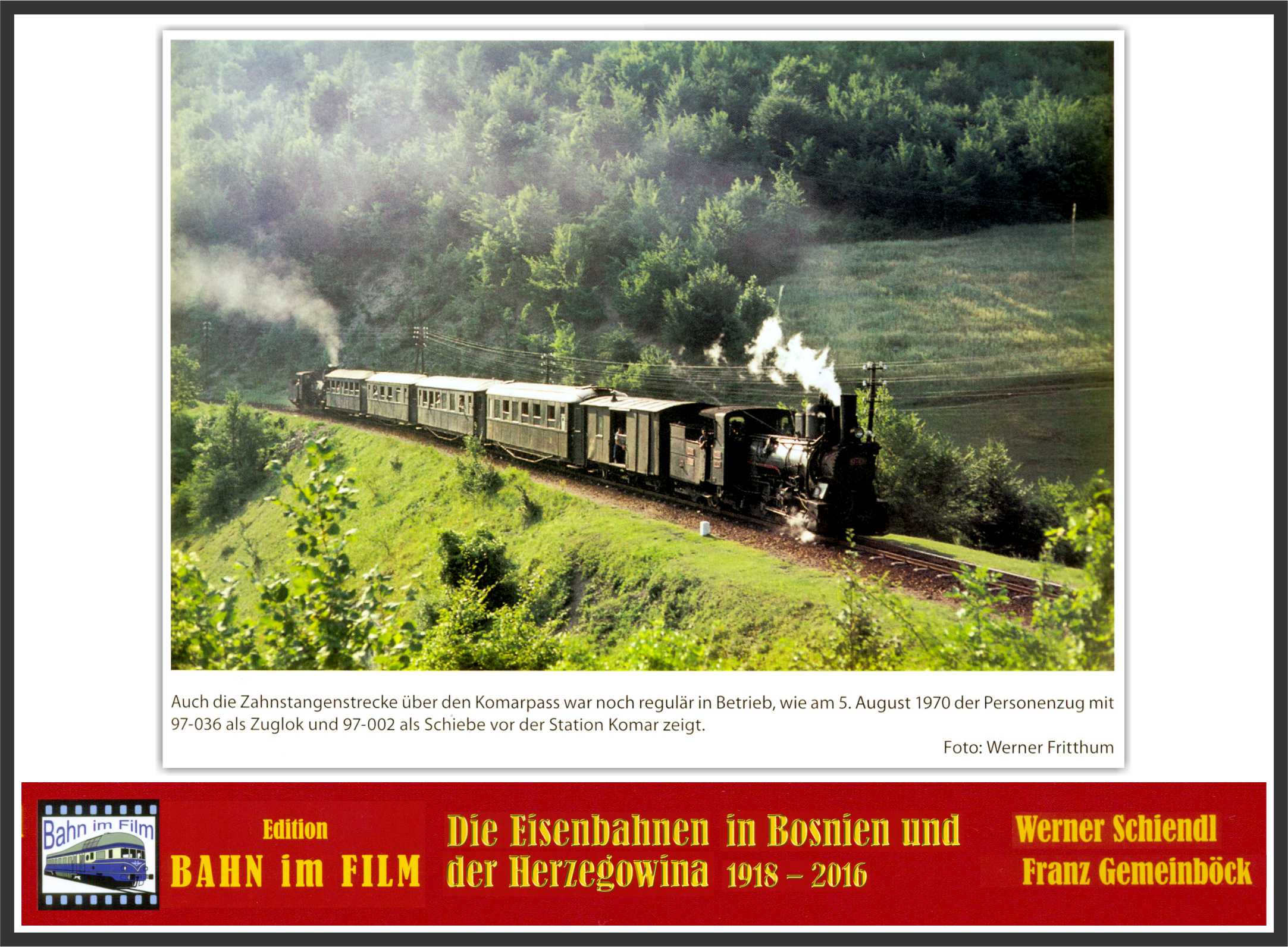

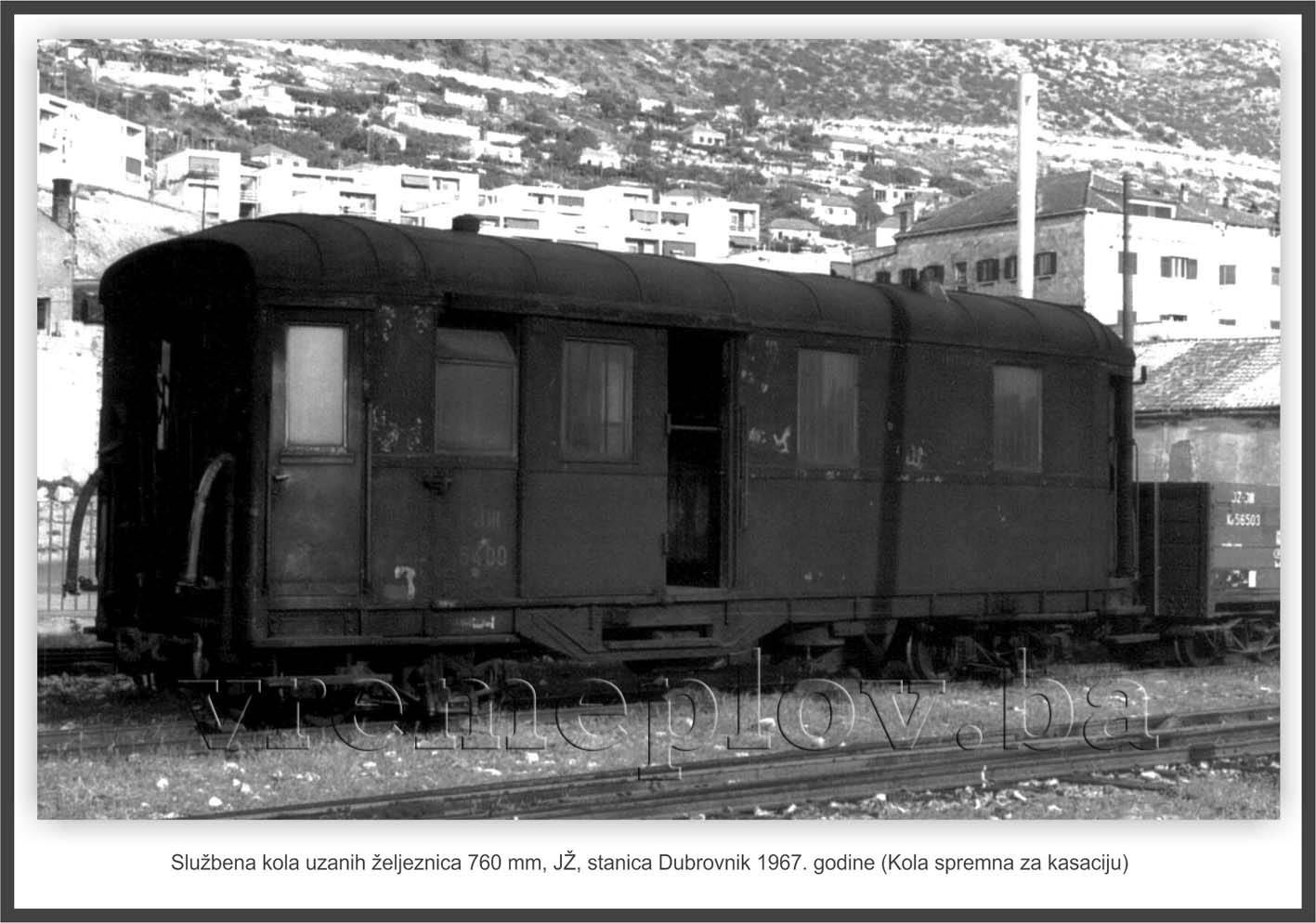

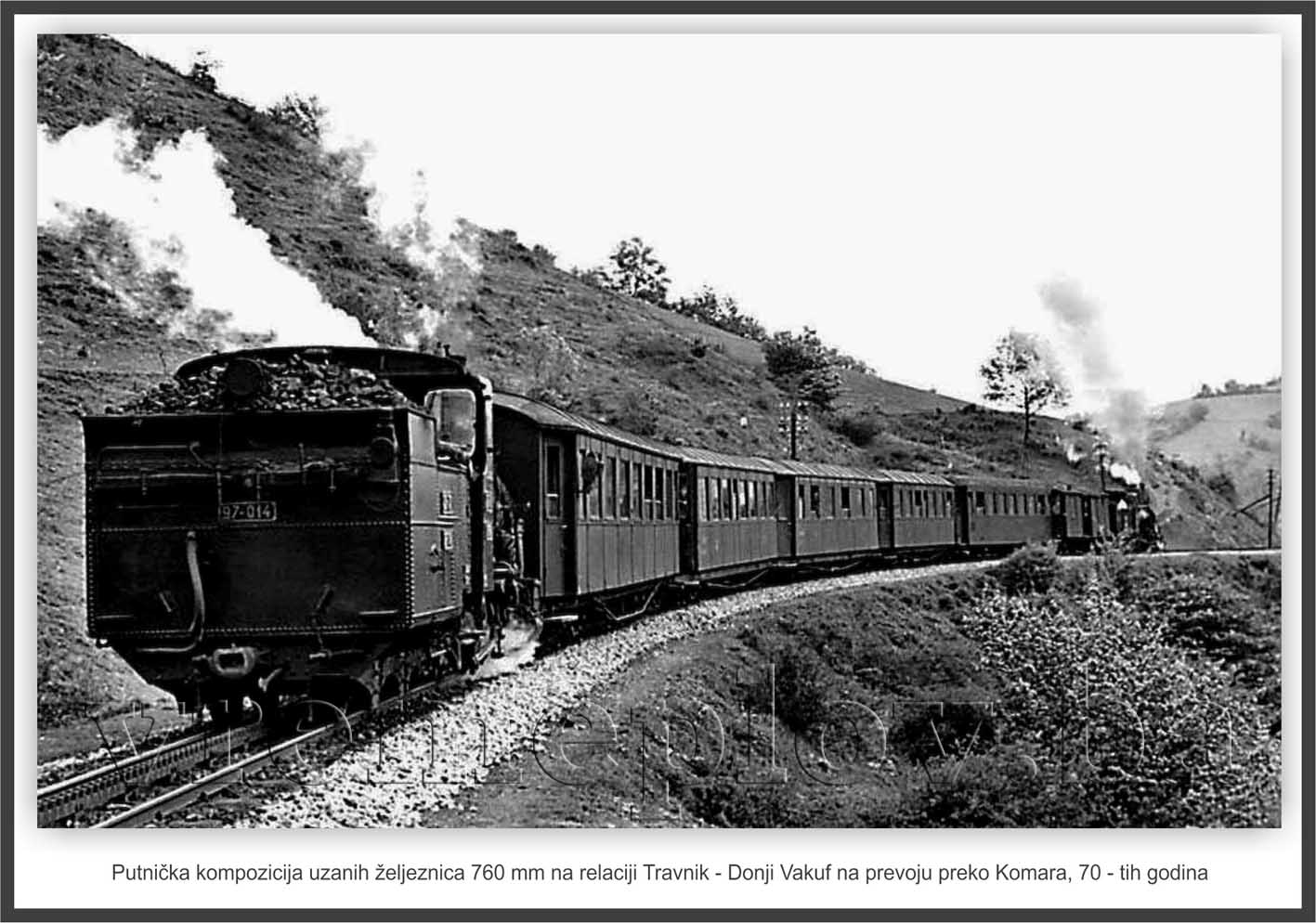

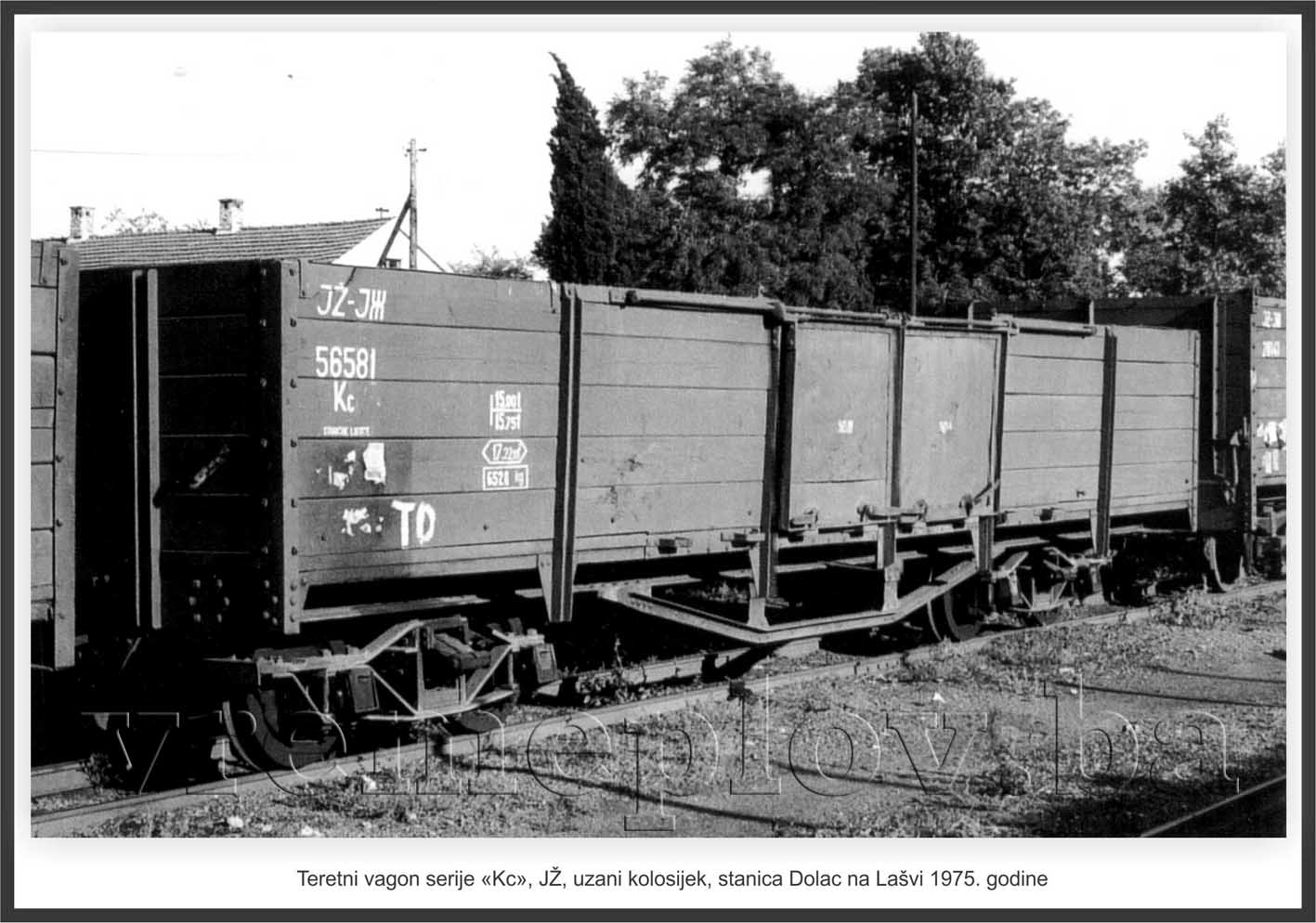

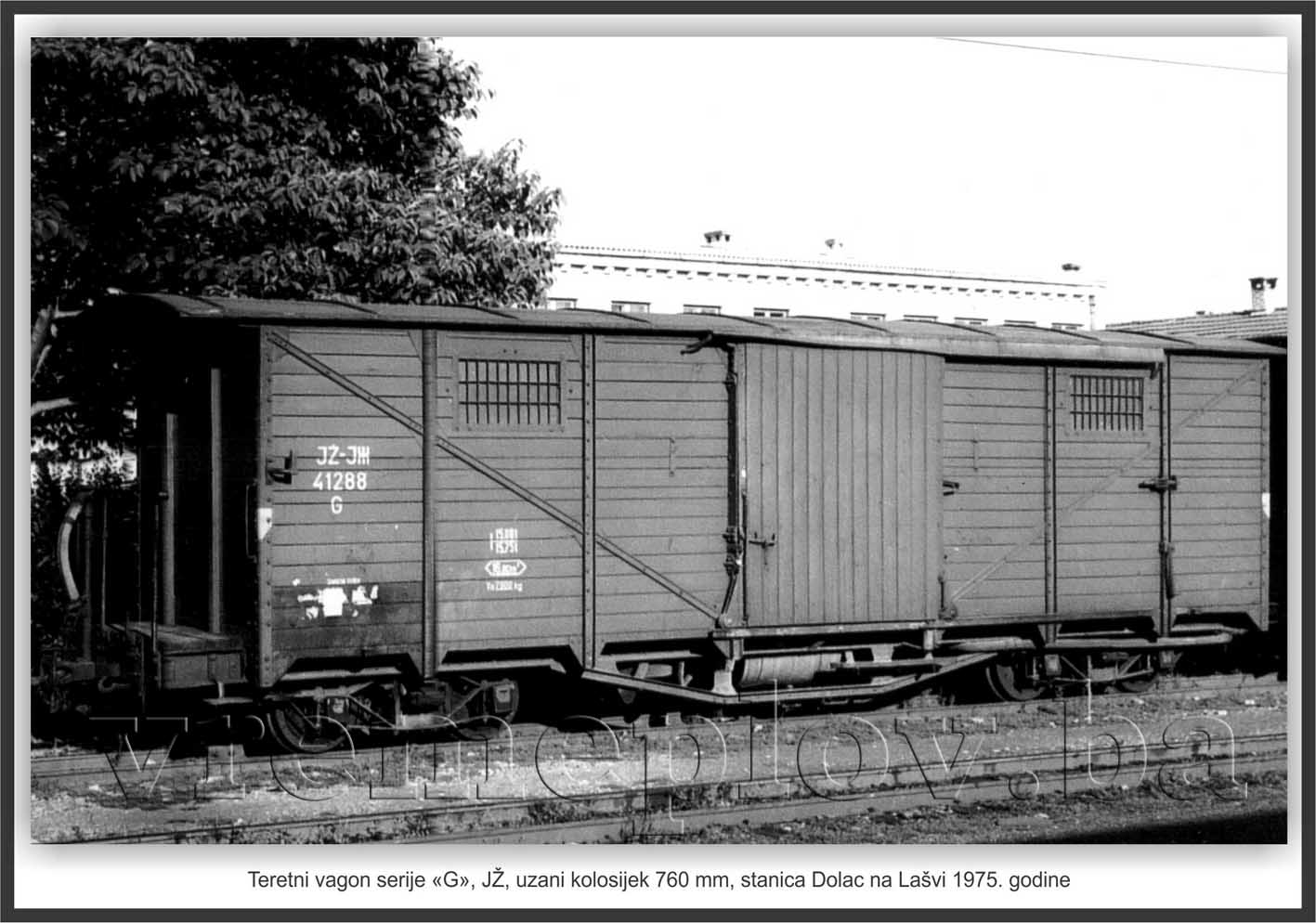

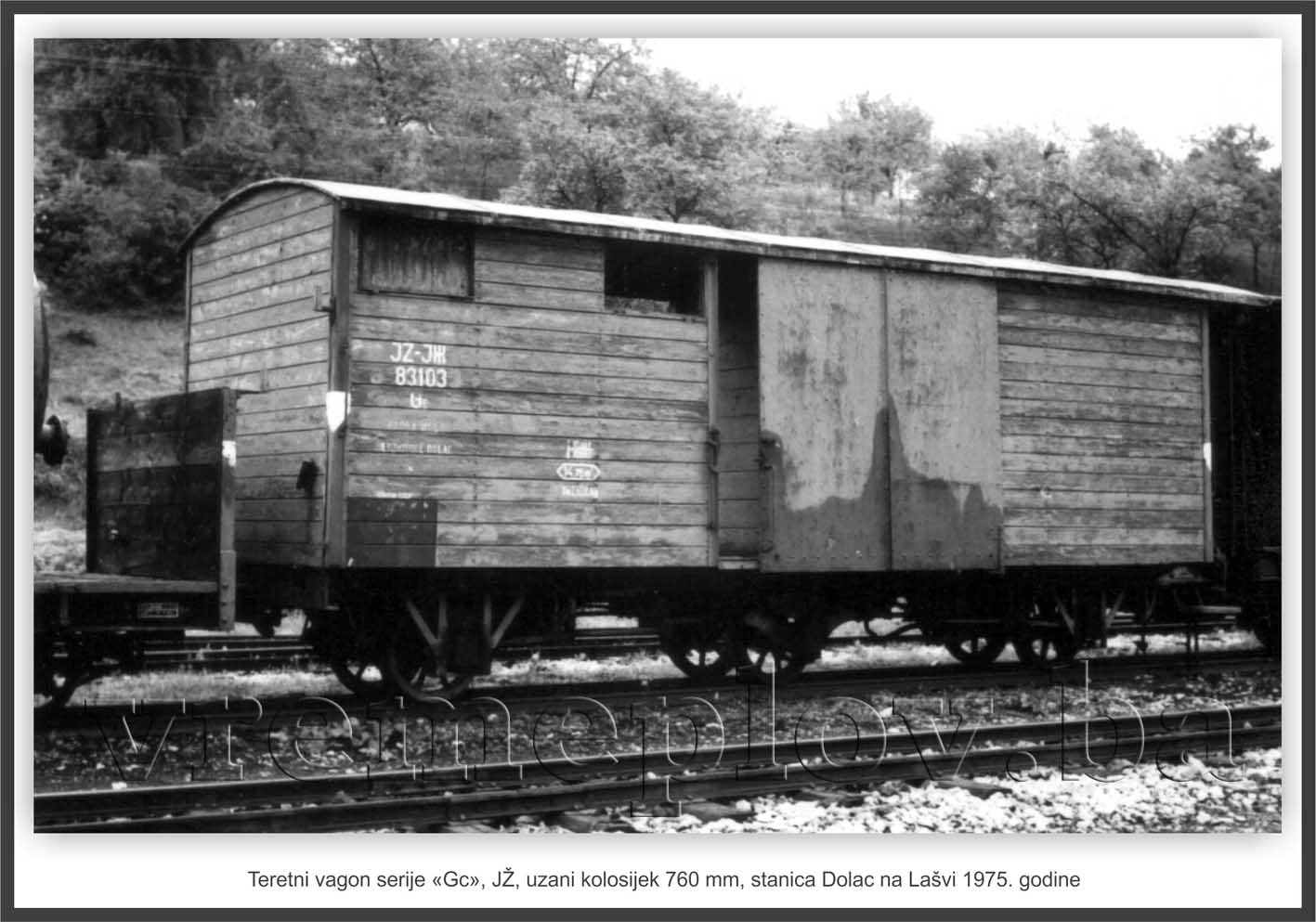

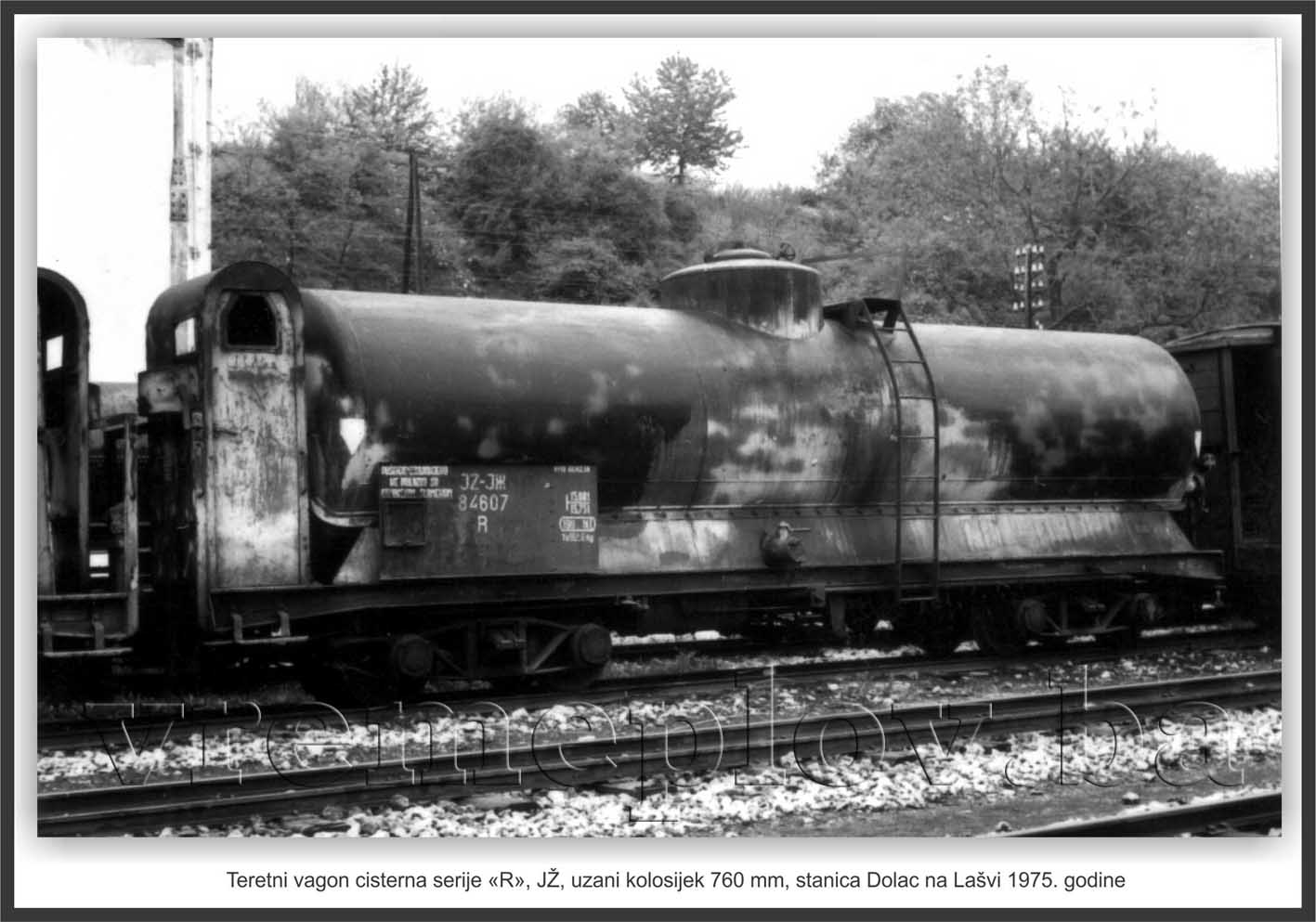

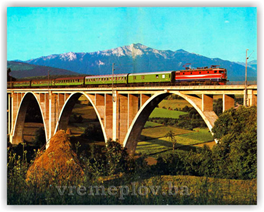

The fate of narrow-gauge railways during the post-war reconstruction and the rebuilding of freight and passenger transport is a completely different reality. Let’s take a moment to recall. At the expense of labor productivity, poor technical equipment, and high exploitation costs in freight and passenger transport, the heroic work was done by narrow-gauge railways, primarily on the main standard-gauge line Šamac – Sarajevo – Ploče. As secondary lines were: Brod – Doboji – Teslić – Pribinić, Zavidovići – Olovo – Kusače, Lašva – Travnik – Donji Vakuf – Bugojno, as well as Donji Vakuf – Jajce – Srnetica, Ilijaš – Okruglica, Semizovac – Ivančići, Sarajevo – (Titov) Užice, with a branch line Ustiprača – Foča – Miljevina. Furthermore, Gabela – Hum – Uskoplje – Dubrovnik, Hum – Uskoplje – Zelenika, and Hum – Trebinje – Bileća – Nikšić. On the main line Doboj – Banja Luka – Bosanski Novi, there were Prijedor – Ljubija and Prijedor – Srnetica – Drvar – Lička Kaldrma. These listings include narrow-gauge lines and dozens of industrial, forest, and mining railways, which, due to “technical feasibility” in the reconstruction of railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina, were completely abolished by government decree starting from the early 1960s and continuing until the late 1970s.

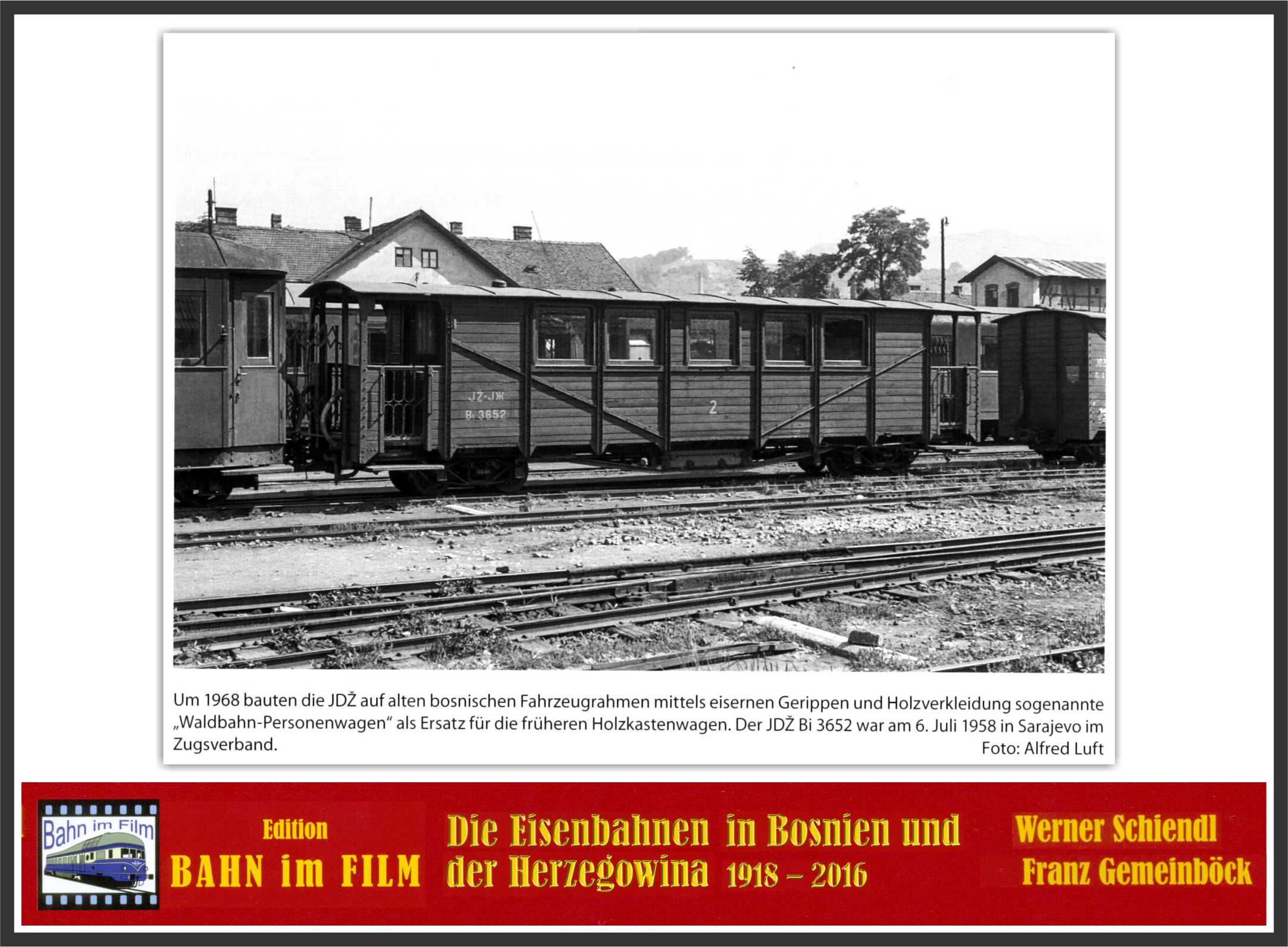

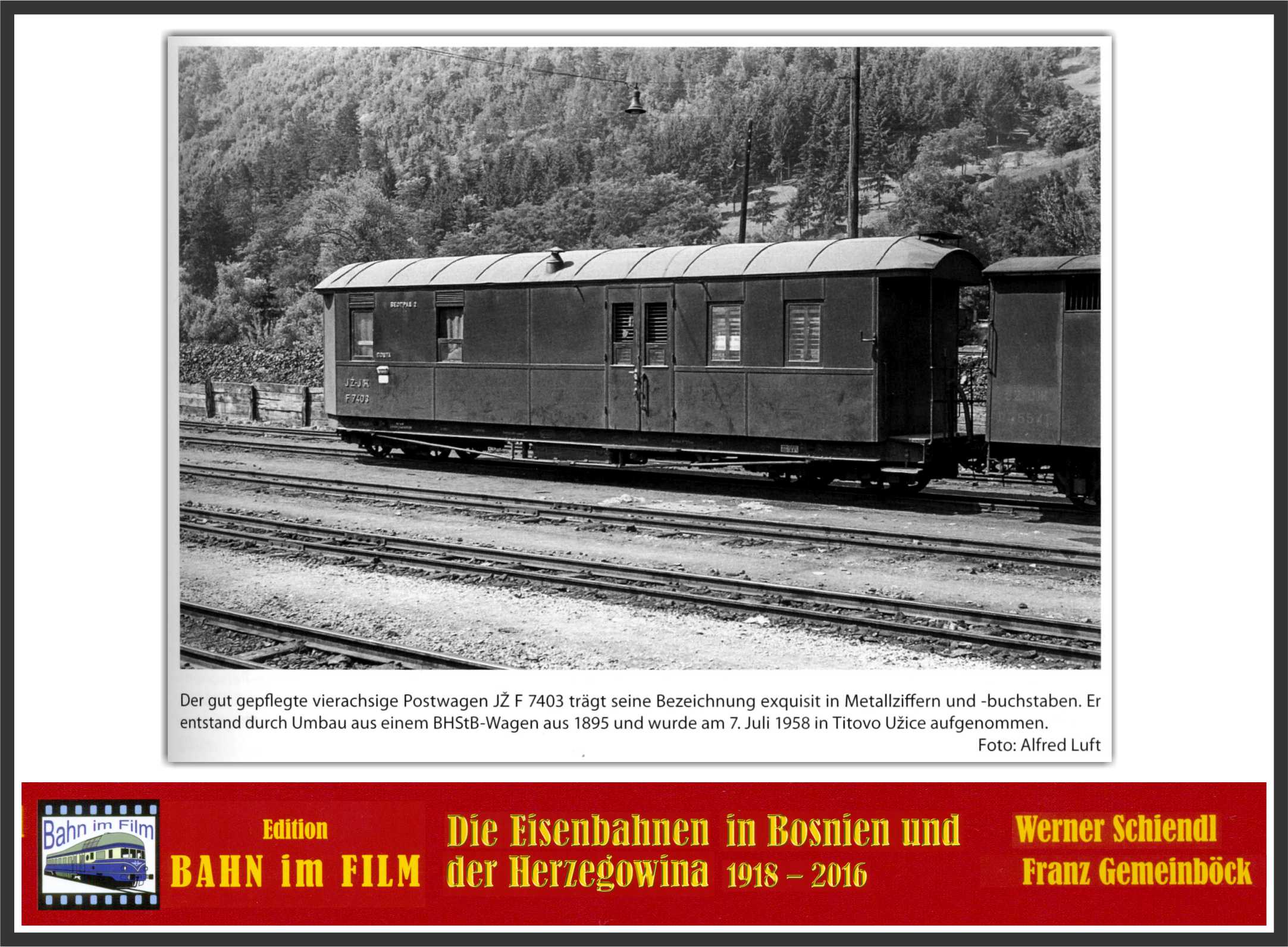

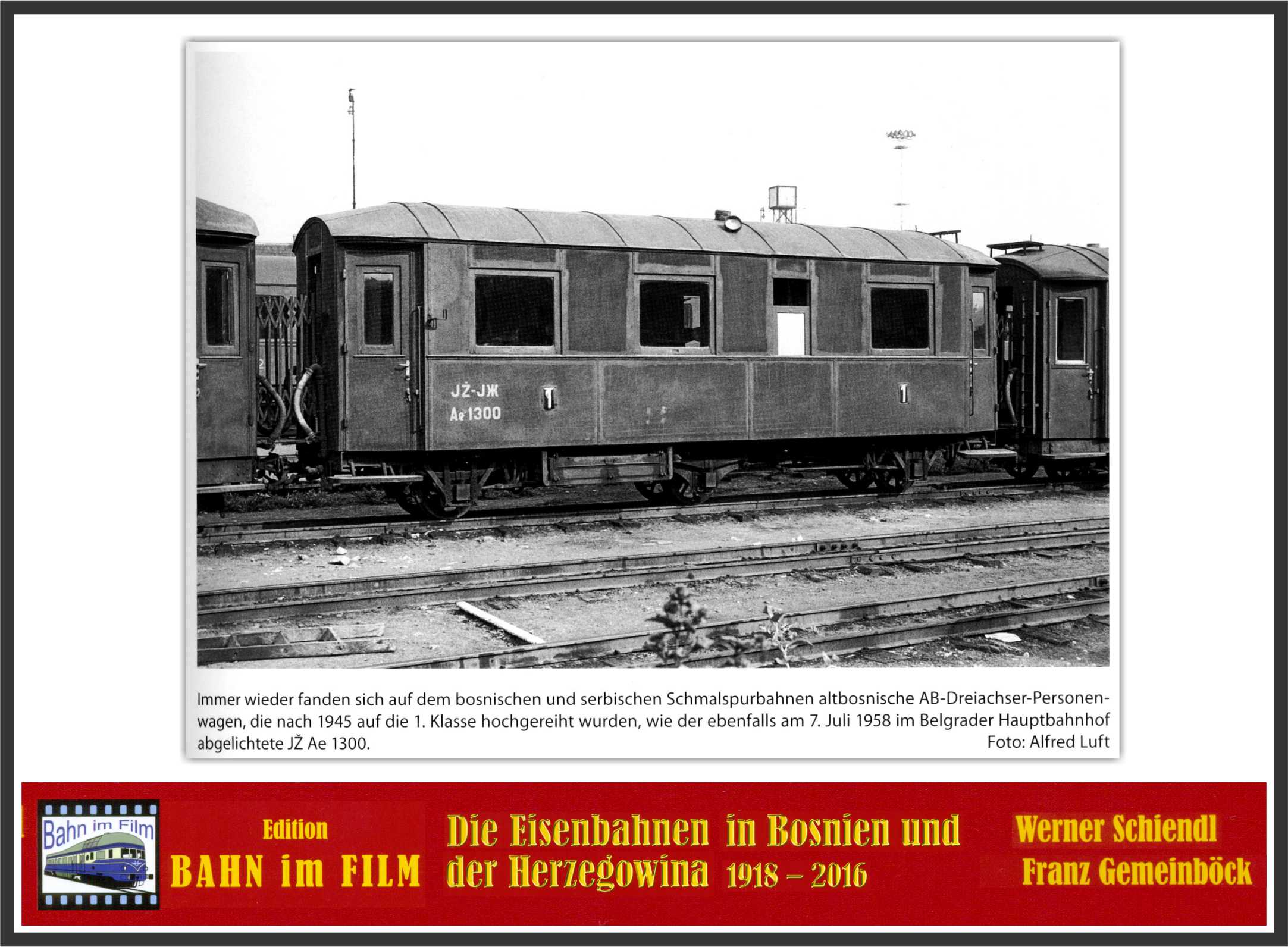

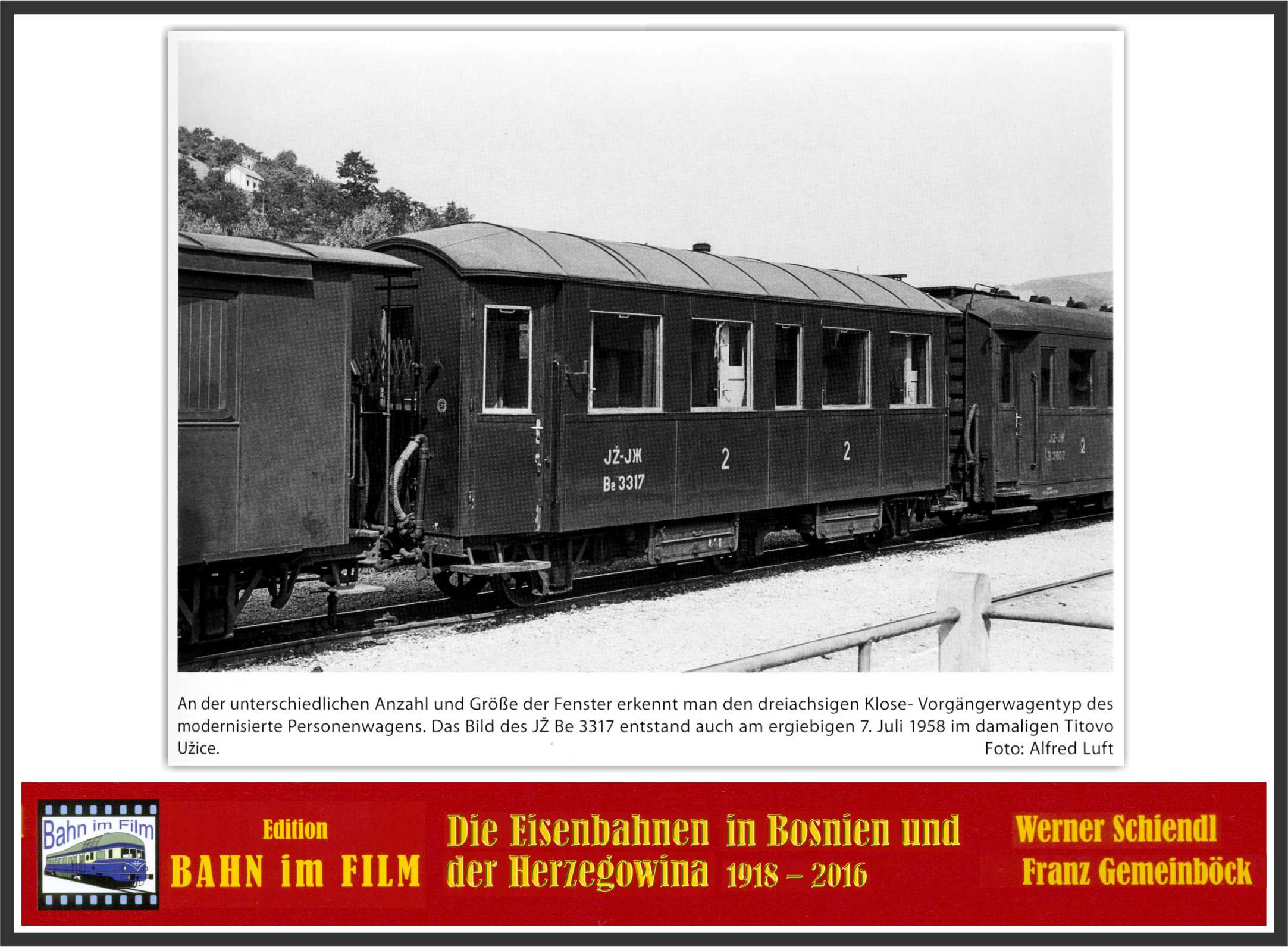

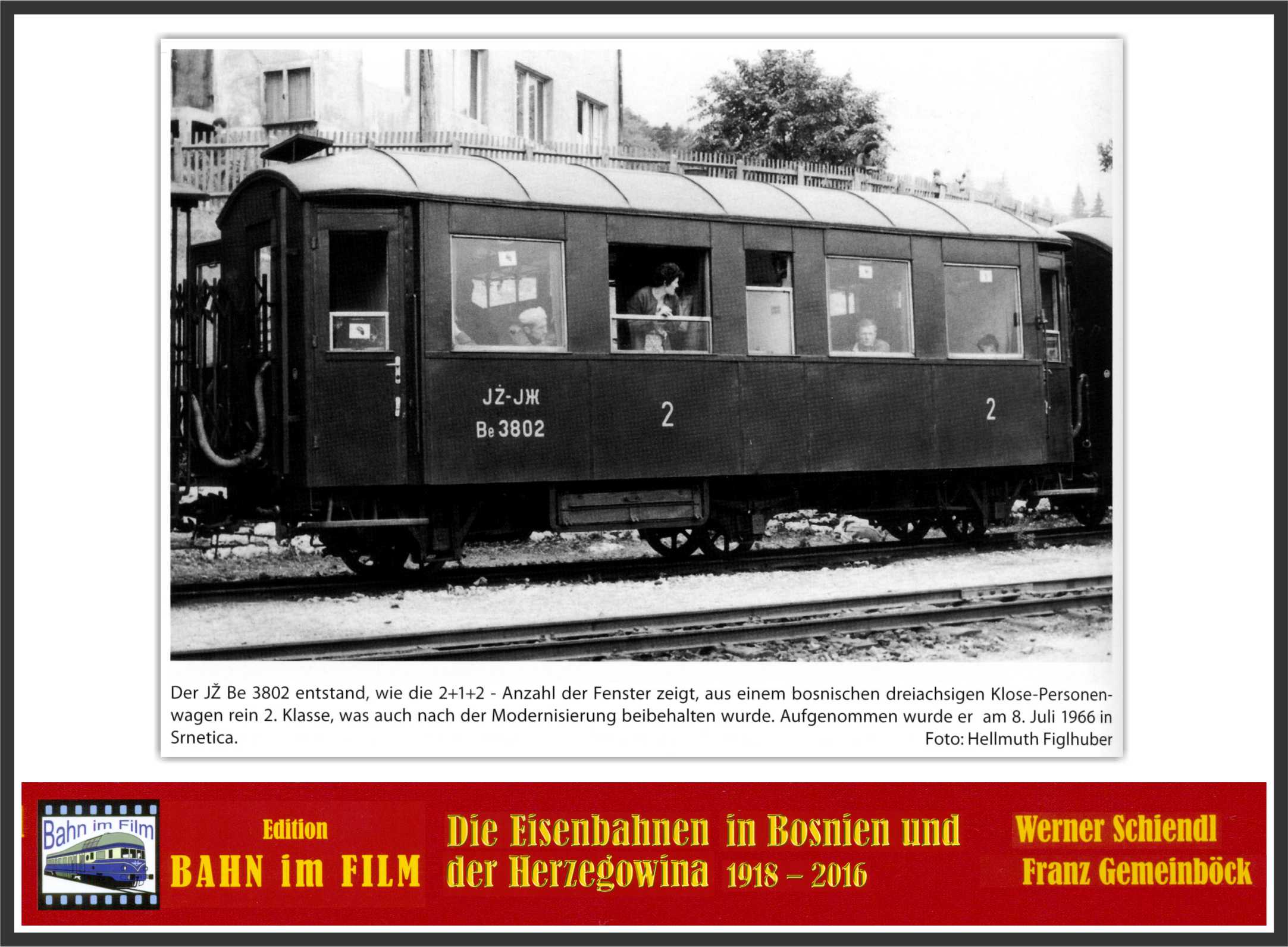

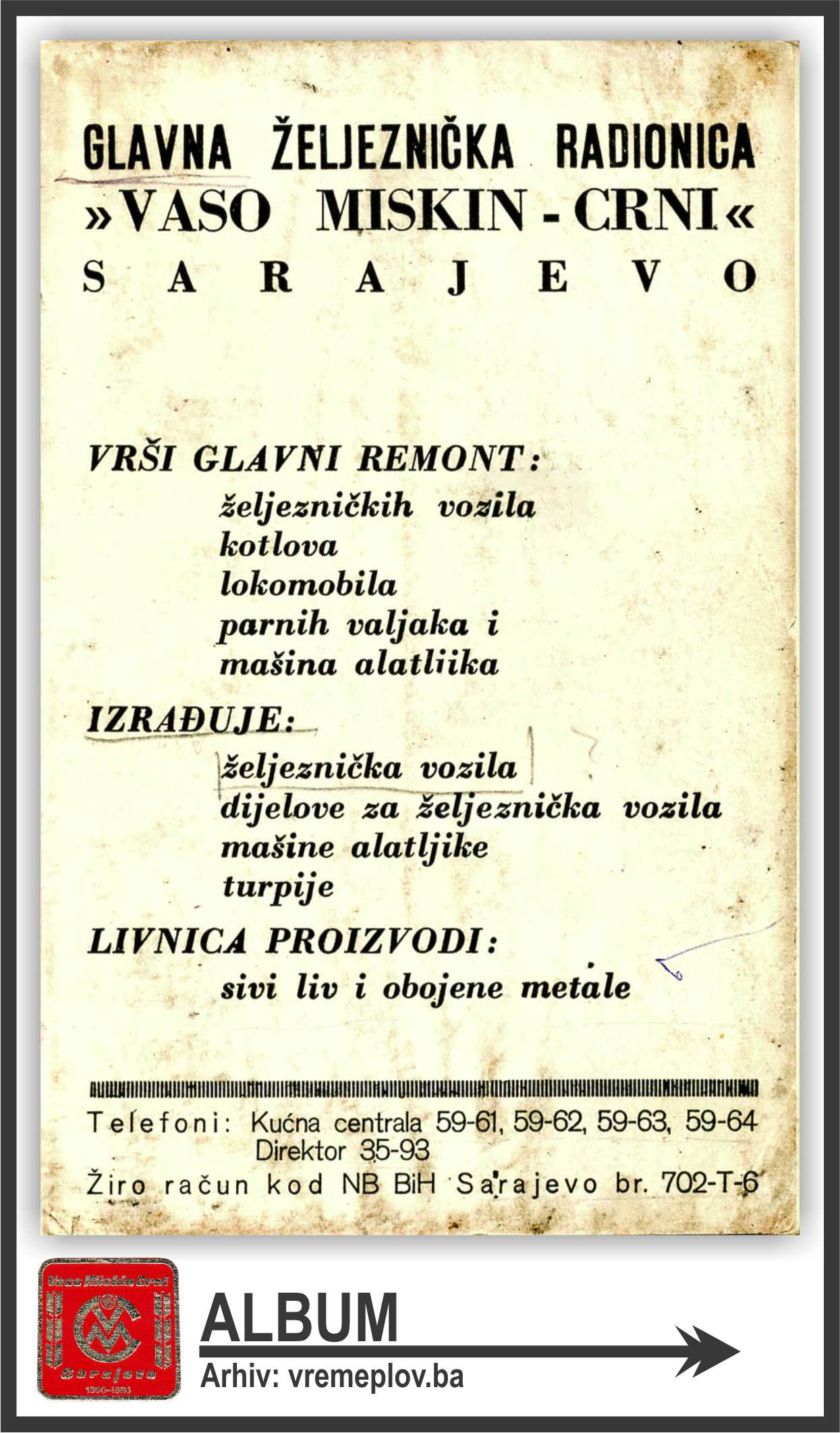

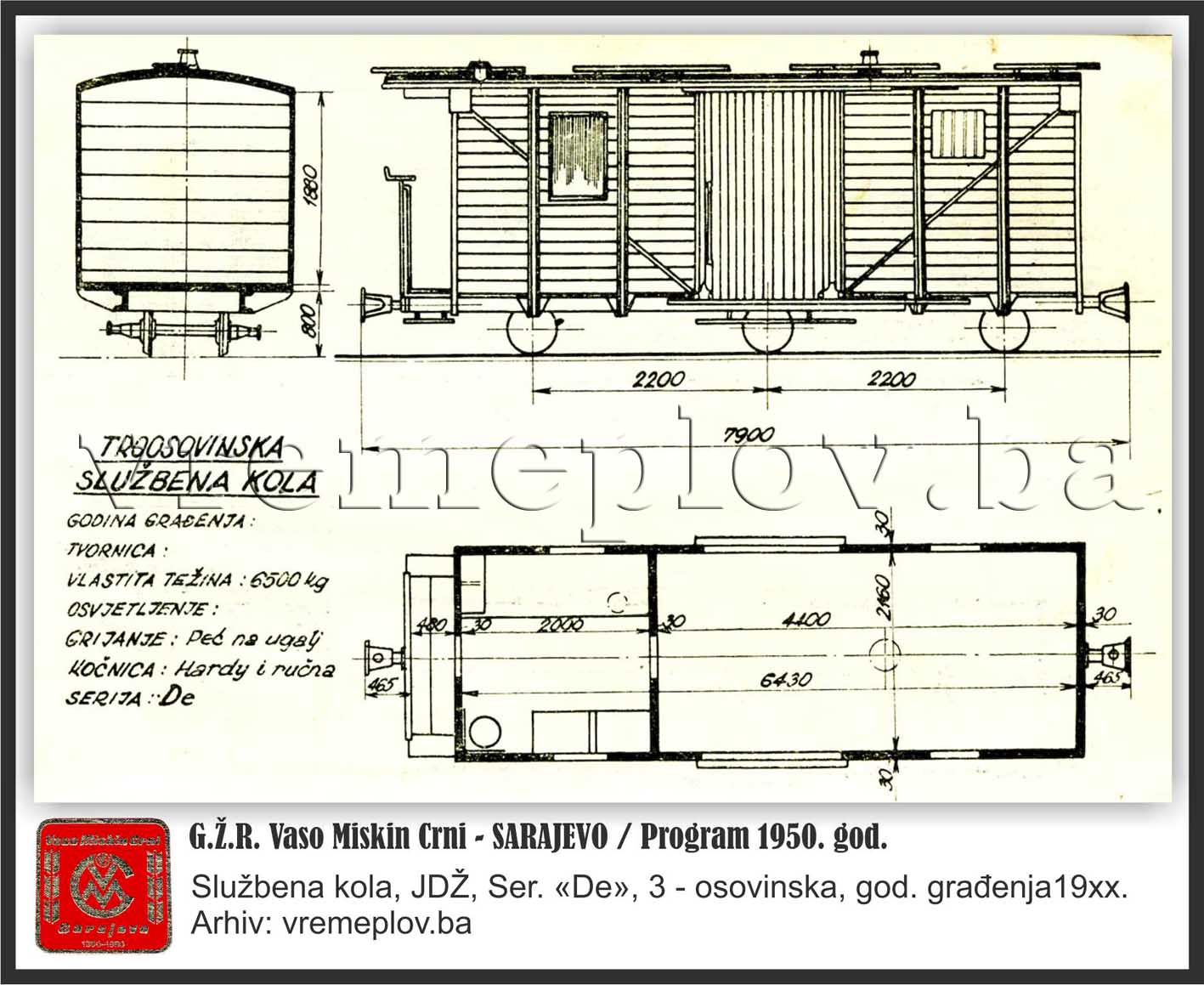

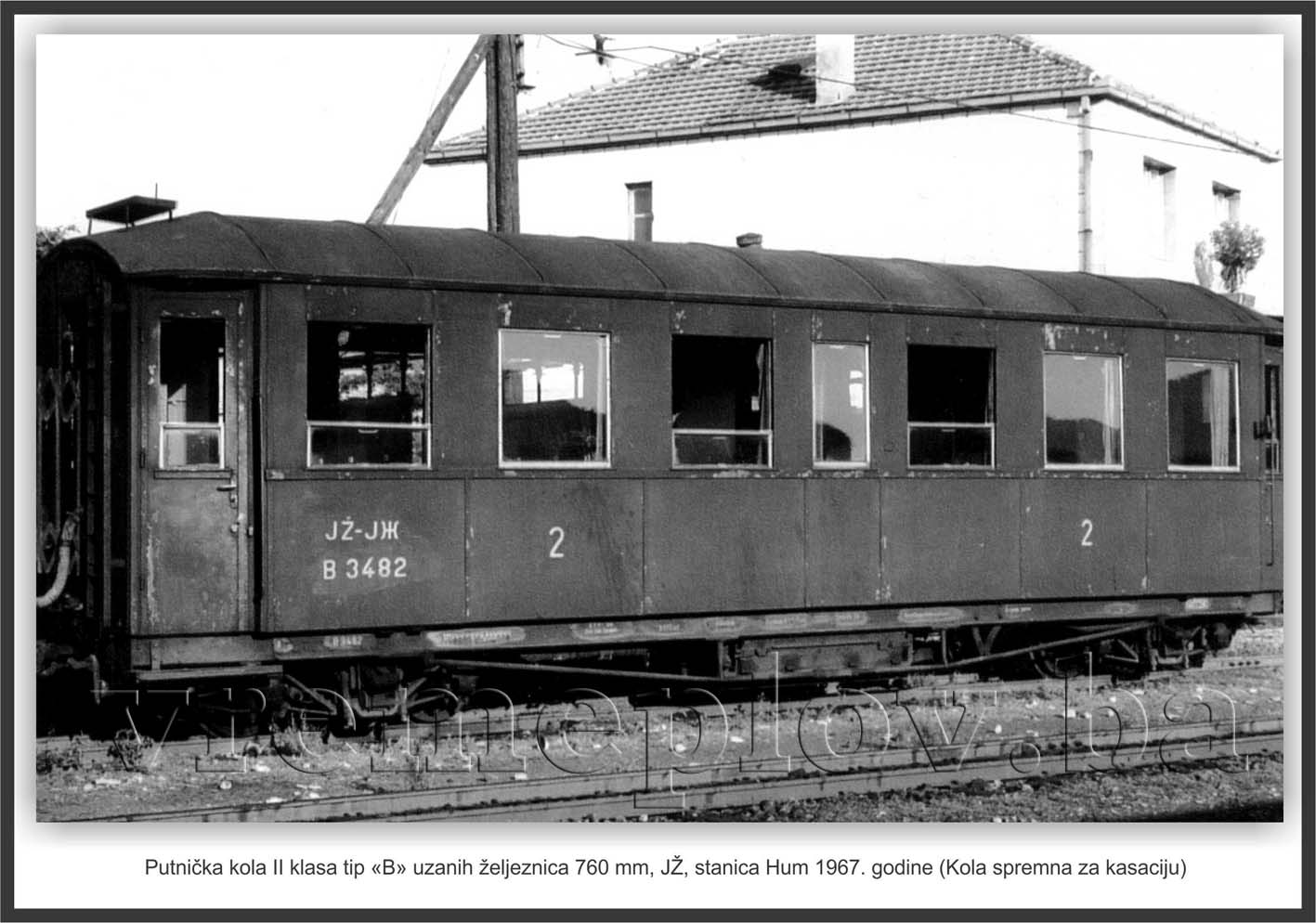

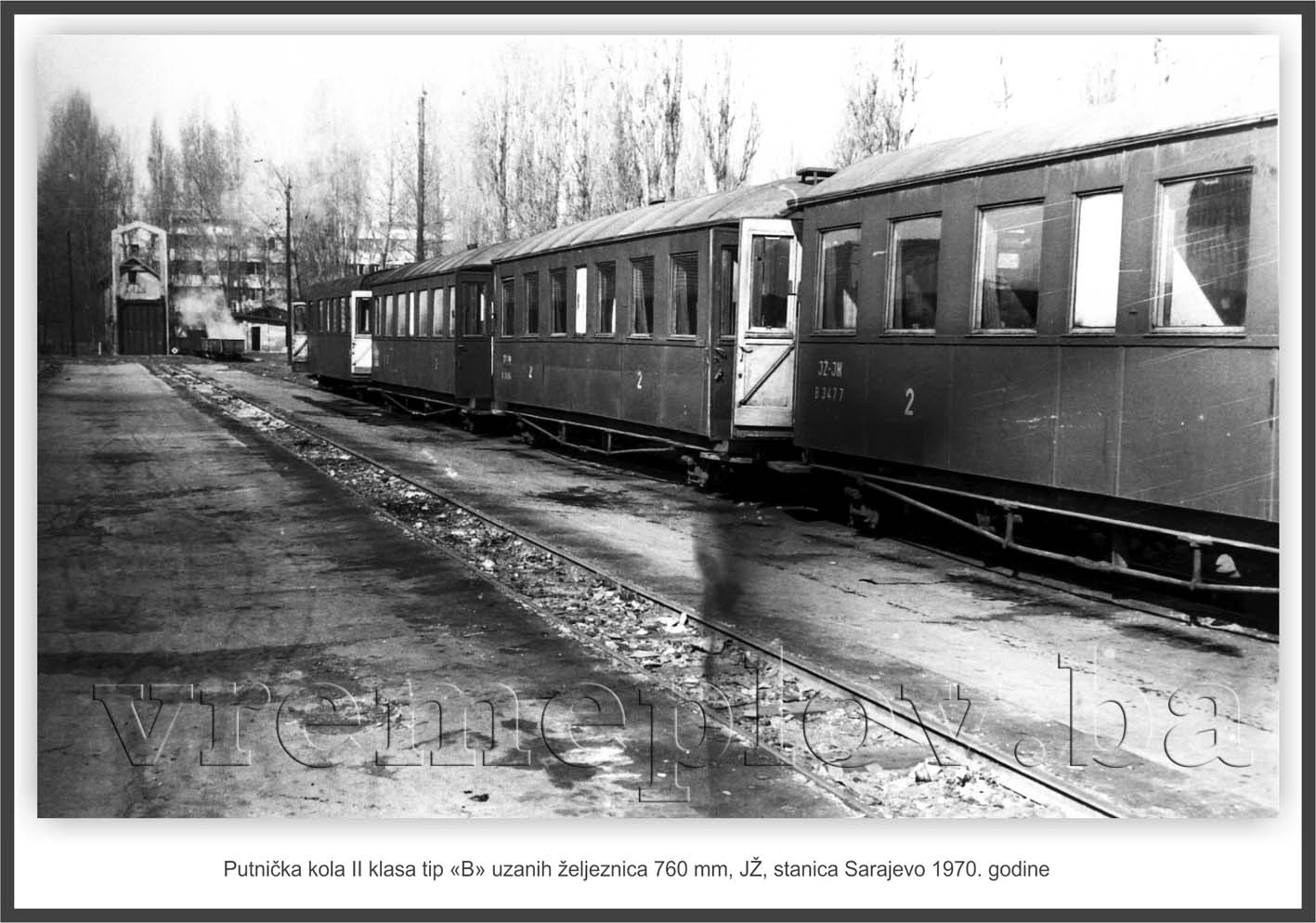

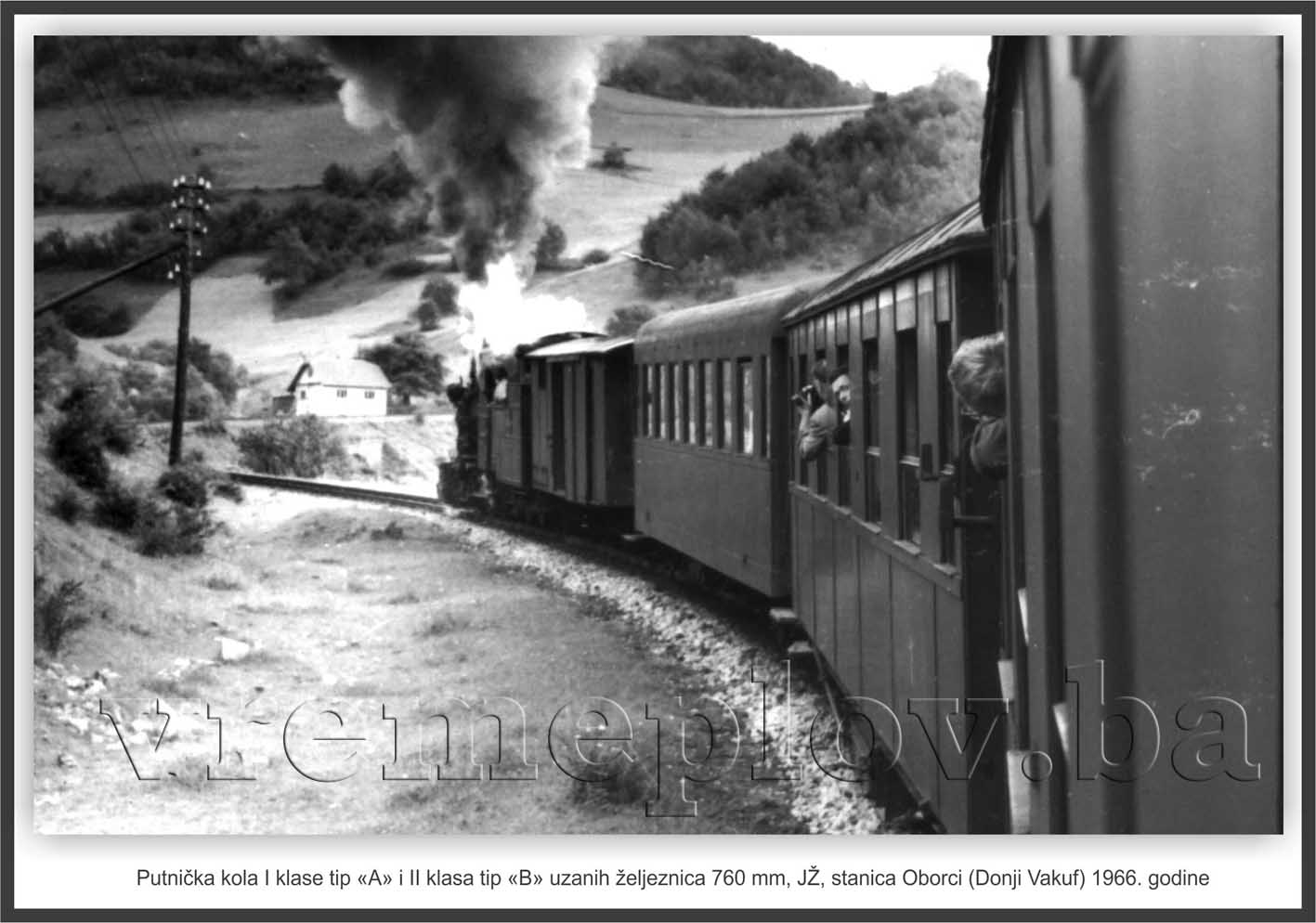

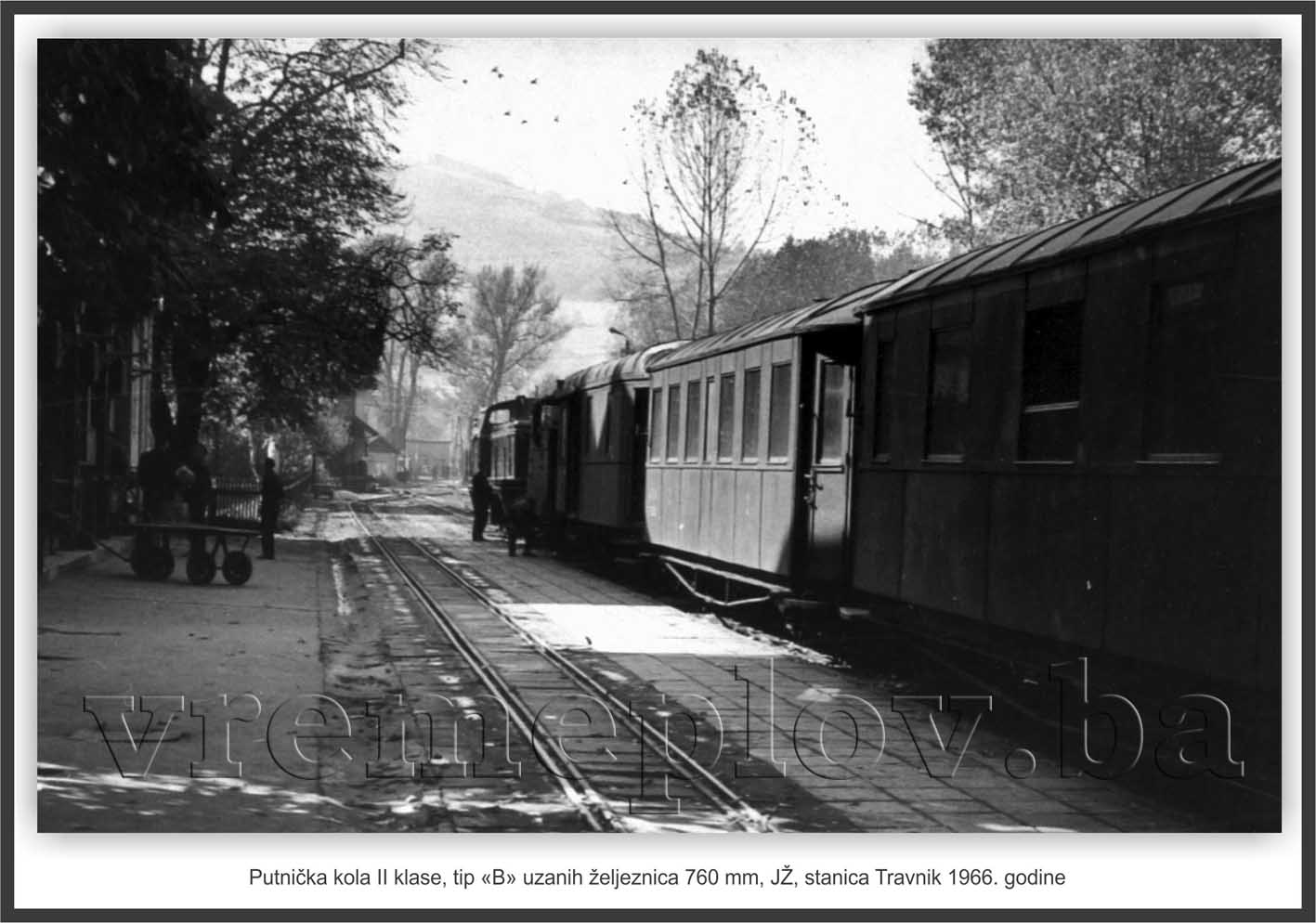

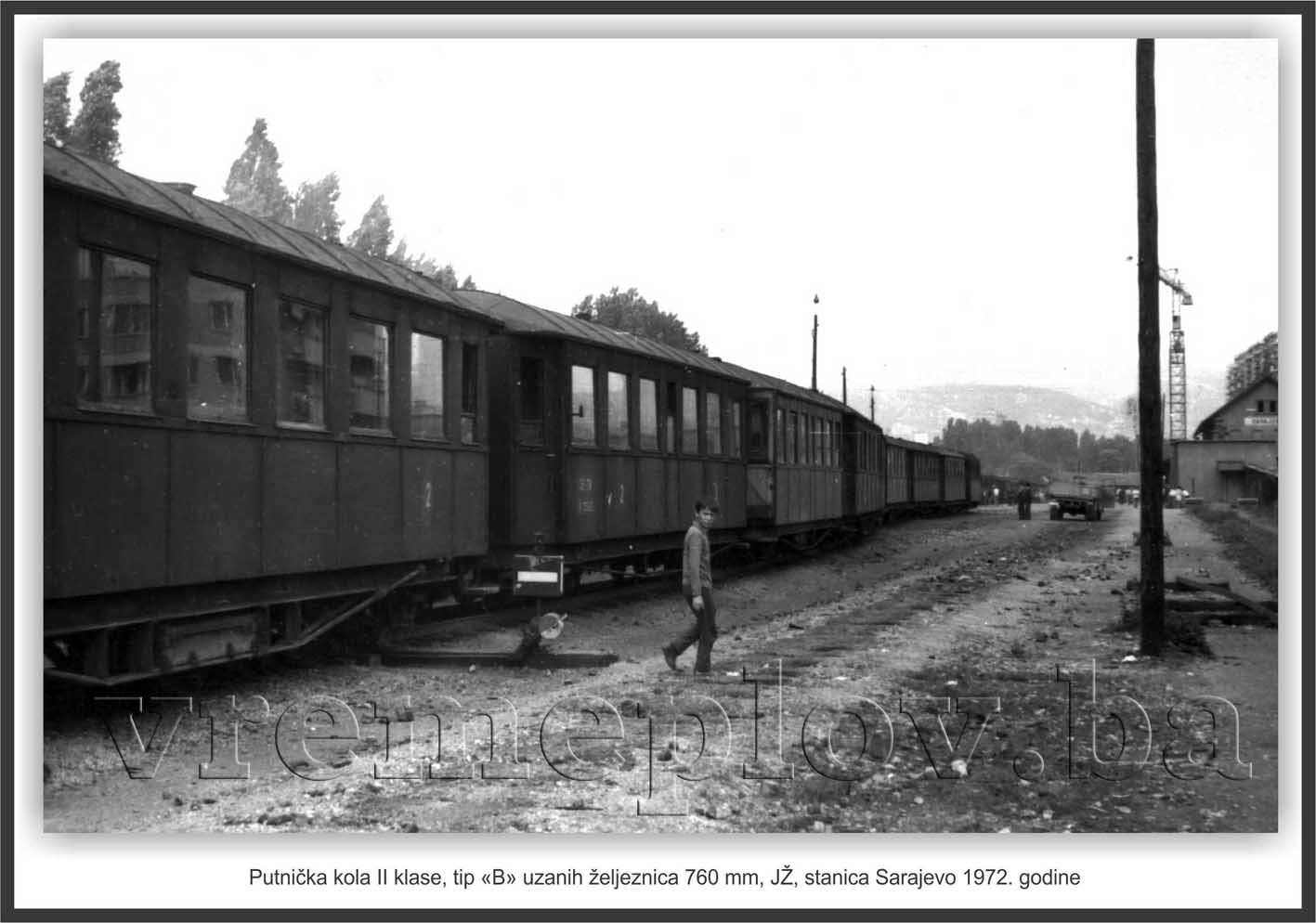

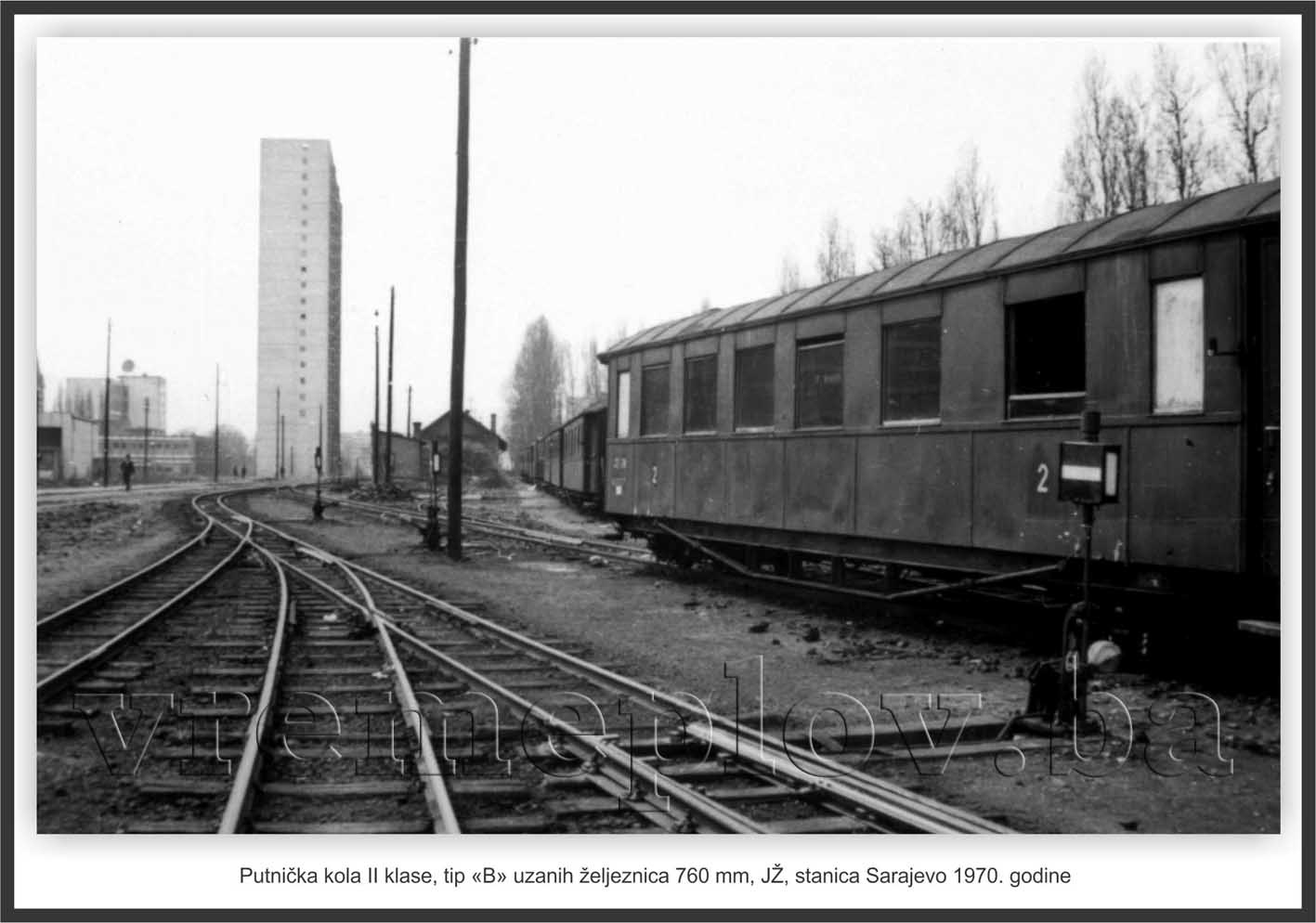

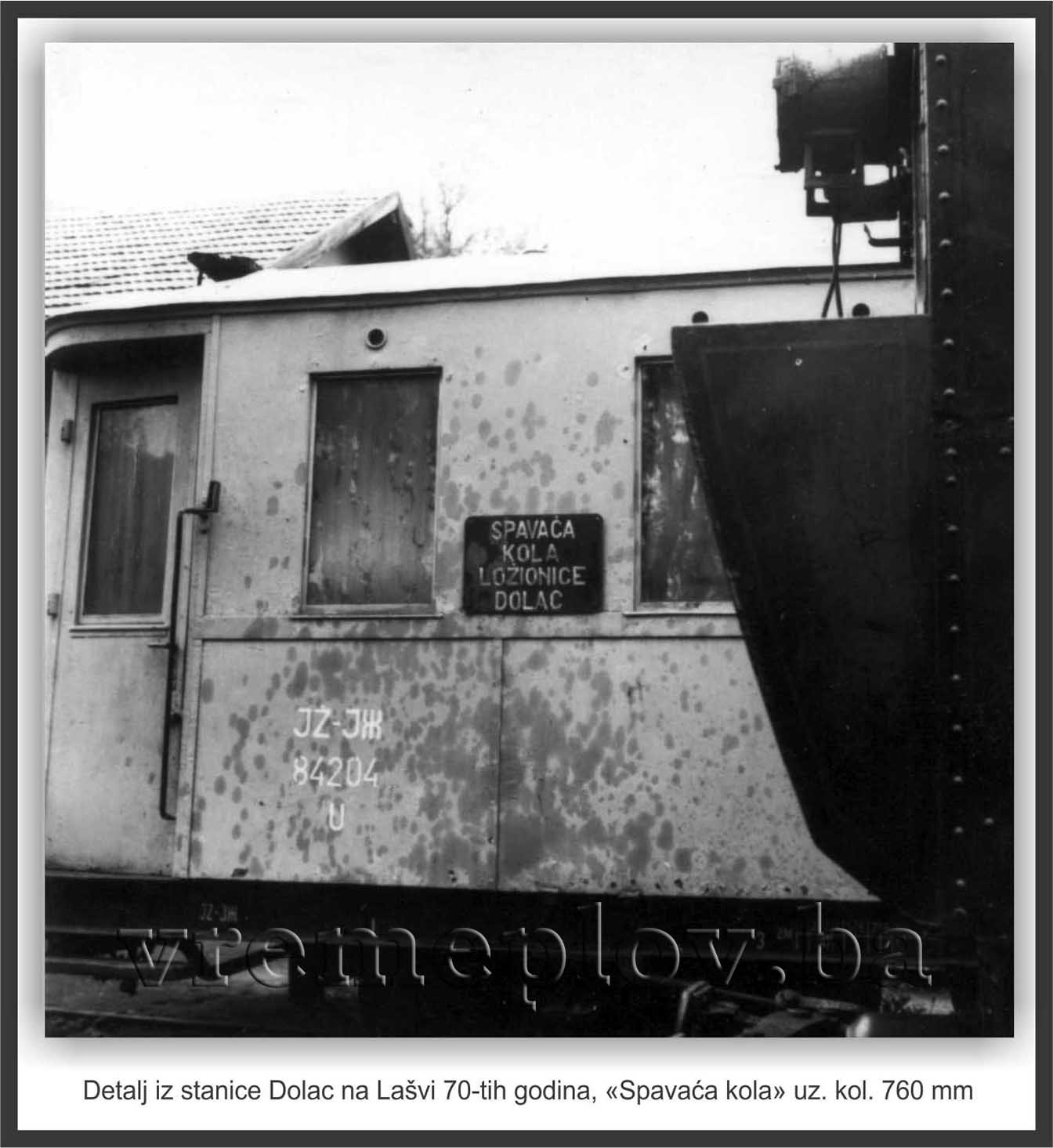

During the period of active exploitation of narrow-gauge tracks, from the end of the war until their abolition (about 35 years), mostly preserved passenger cars of all classes and series were in operation. Thanks to the construction of new standard gauge tracks, the need to acquire narrow-gauge passenger cars was not a priority for the Sarajevo Directorate at that time. Class IV cars were phased out. Class II and III cars, mostly with wooden framing (two- and three-axle), operated on “branch” lines. Class I (“A”) and Class II (“B”) cars, as well as mixed (“AB”) cars, generally with metal bodies (the “Antonijević” four-axle cars), operated on the narrow tracks between Sarajevo – Višegrad – Belgrade, Čapljina – Gabela – Hum – Trebinje – Bileća, or Hum – Ustikolina – Dubrovnik, and Ustikolina – Zelenika. In the course of railway operations, motor railcars from series 801 and 802 played a significant role in passenger transport. Workshops for repairing and maintaining narrow-gauge cars and railcars were: the Main Railway Workshop “Vaso Miskin Crni”, the Railway Workshop in Čapljina, Alipašina Bridge, Bosnia-Srebrenica, Doboj, Zenica, Prijedor, Drvar, and several smaller workshops for minor and medium repairs.

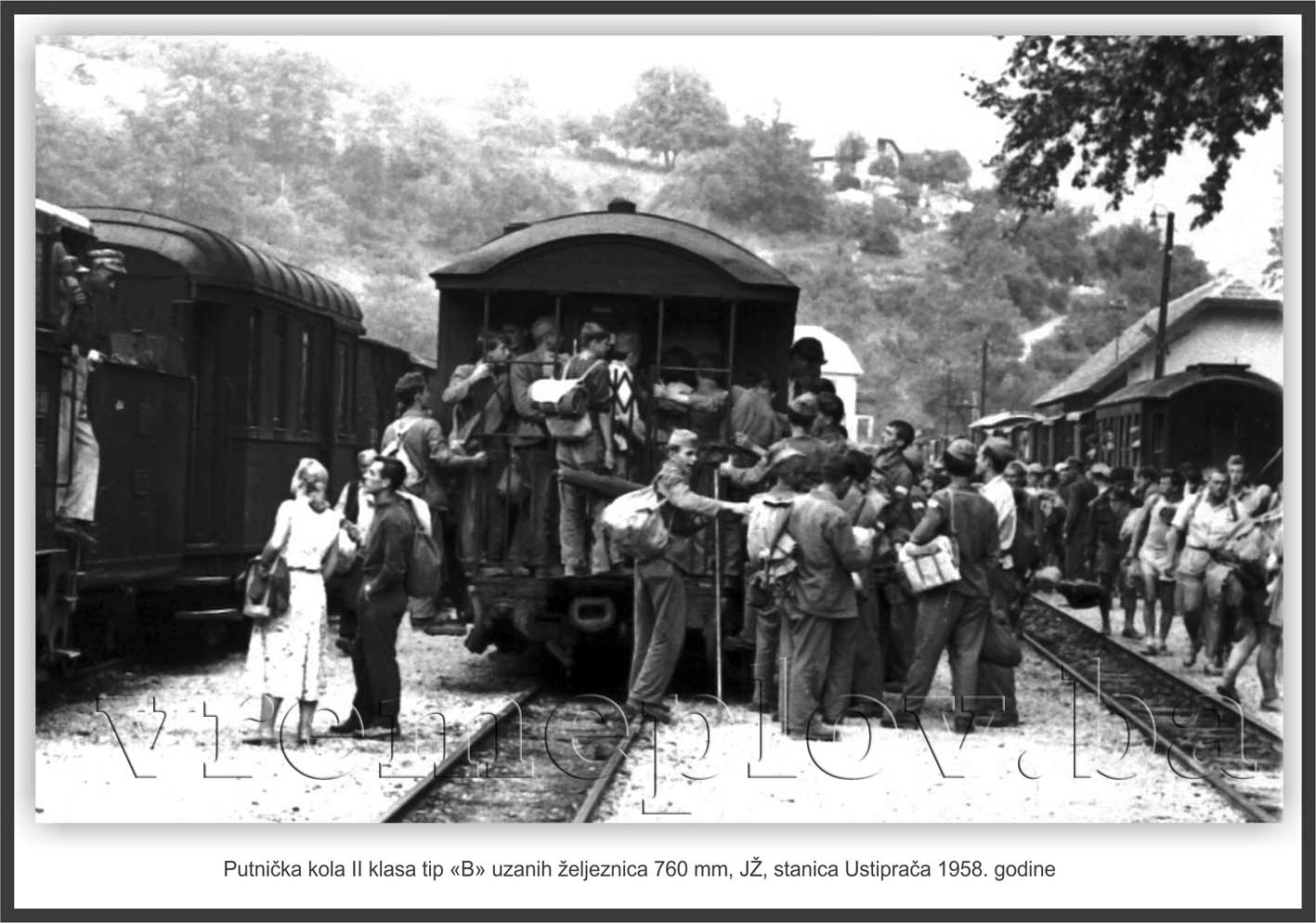

It should be noted that during the period of “Workers’ Self-Management,” workers mostly used their annual vacations on the Adriatic Sea. For example, solely on the narrow-gauge railway route Čapljina – Gabela – Zelenika, at its peak times, about 960,000 passengers were transported annually. The Railways of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina have never achieved this result on an annual basis from 1996 to today (2019). Likewise, on the Vrpolje – Sarajevo route (normal gauge railways), about four million passengers were transported annually, while during the era of mass railway transport in Bosnia and Herzegovina, approximately 23 million passengers were carried annually. Just recall the industrial and economic centers along the Šamac – Sarajevo line, such as: Modriča (Refinery), Doboj (as an economic hub and direction toward the Tuzla basin), Maglaj (Natron), Zavidovići (Krivaja Complex), Žepče (wooden, textile, and leather industries), Zenica (Steelworks), Kakanj (Cement), Visoko (Leather industry), and finally Sarajevo (Vaso Miskin Crni Workshop, Wire Factory, Energoinvest, etc.).

With the electrification of the Vrpolje – Ploče line in 1971, the conditions were created to launch the first international train on the Ploče – Stuttgart line, numbered 296/297. Additionally, fast and business trains (“Sarajevo Express” and “Bosna Express”) were introduced to Zagreb, Belgrade, Ljubljana, and Subotica. On the eve of the Winter Olympic Games in Sarajevo, new electric multiple units (Ganz–MÁVAG Budapest series 411/415) were added, named “Olympic Express,” heading towards Zagreb, Belgrade, Novi Sad, and Ploče (formerly Kardeljevo), and soon after, new business trains “Bosna Express” towards Zagreb and Belgrade.

Railways in Bosnia and Herzegovina after 1996

Bosnia and Herzegovina has a total of 1,030.389 km of track (8.52% double-track) at a scale of 1435 mm. The rail network (according to Dayton) is distributed with 57% in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 40.4% in Republika Srpska, and 2.6% in the Brčko District. About 76% of the network is electrified with a single-phase system of 25 kV, 50 Hz.

The first passenger trains from Sarajevo to Ploče (Croatia) were launched in 1998. Trains Sarajevo – Zagreb and Sarajevo – Budapest have been operating since 2001, and the trains on the line from Ploče to Zagreb since 2002. On the Sarajevo – Belgrade line, two trains have been running since 2009. In 2012, the international train lines to Belgrade, Budapest, and one (night) train to Zagreb were discontinued. The Sarajevo – Zagreb (daily) train service ended in December 2015. All the above-mentioned international trains that used to travel to Europe have not been operating since 2012 or 2015, and all railway traffic now occurs within the borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

As we initially wrote in this article about the “Bosnian narrow-gauge railway” and the rail “blind loop” for international passenger traffic, it is indicative that after 140 years, Bosnia and Herzegovina is once again returning to the era of narrow-gauge construction, even though it is land-connected via railway tracks to the south, north, and west of Europe. Whether the solution lies in political nature or market economy, judge for yourselves.

We suggest taking a look at a modest gallery of pictures that tell the story of the development history of narrow-gauge rolling stock in Bosnia and Herzegovina.